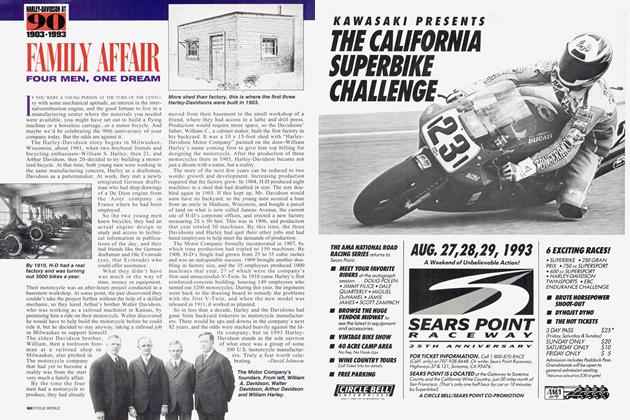

10 YEARS AFER

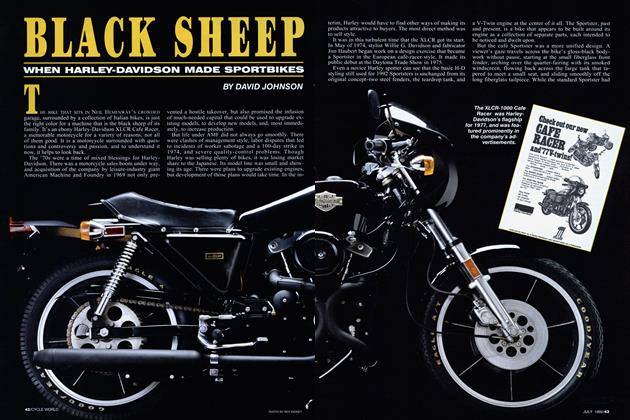

THE SHORT, UNHAPPY LIFE OF HARLEY-DAVIDSS XR-1000

DAVID JOHNSON

RUMORS WERE DRIFTING like smoke in the late 1970s, blown by the winds of desire: A streetlegal XR-750 flat-tracker was coming from Harley-Davidson.

To enthusiasts, the idea seemed a natural. The alloy XR had proven itself in the rigors of racing, and since the tooling and many of the hard parts needed for the conversion already existed, producing a street XR-750 should be just a matter of fabricating enough brackets and running enough wires to accommodate a horn, a headlight, a taillight and other street necessities. Individuals, including engineers at HarleyDavidson, had made such conversions.

But individuals don’t face the same obstacles as manufacturers, for manufacturers have to satisfy the federal government. The July, 1980, issue of Cycle World had an artist's conception of what a road-going XR-750 might look like, and then told readers that this was “the Harley we'll never see." Why not? Lack of time and engineering manpower, said the factory. According to later accounts, Harley also concluded that making the XR-750 road-ready would have added pounds and cost horsepower, so that the bike would have lost the performance riders justifiably expected.

But enthusiasts kept hoping, and were rewarded in 1983 with the XR1000, though it soon became apparent that the new bike was not going to fulfill their expectations.

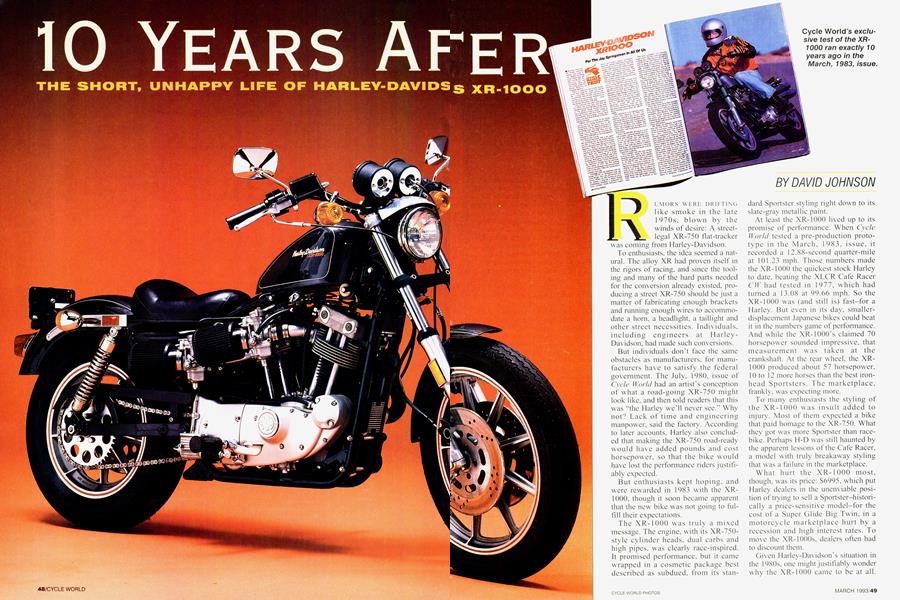

The XR-1000 was truly a mixed message. The engine, with its XR-750style cylinder heads, dual carbs and high pipes, was clearly race-inspired. It promised performance, but it came wrapped in a cosmetic package best described as subdued, from its stan-

dard Sportster styling right down to its slate-gray metallic paint.

At least the XR-1000 lived up to its promise of performance. When Cycle World tested a pre-production prototype in the March, 1983, issue, it recorded a 12.88-second quarter-mile at 101.23 mph. Those numbers made the XR-1000 the quickest stock Harley to date, beating the XLCR Cafe Racer CW had tested in 1977, which had turned a 13.08 at 99.66 mph. So the XR-1000 w'as (and still is) fast-for a Harley. But even in its day, smallerdisplacement Japanese bikes could beat it in the numbers game of performance. And while the XR-1000’s claimed 70 horsepower sounded impressive, that measurement was taken at the crankshaft. At the rear wheel, the XR1000 produced about 57 horsepower, 10 to 12 more horses than the best ironhead Sportsters. The marketplace, frankly, was expecting more.

To many enthusiasts the styling of the XR-1000 was insult added to injury. Most of them expected a bike that paid homage to the XR-750. What they got w^as more Sportster than racebike. Perhaps H-D was still haunted by the apparent lessons of the Cafe Racer, a model with truly breakaway styling that was a failure in the marketplace.

What hurt the XR-1000 most, though, was its price: $6995, which put Harley dealers in the unenviable position of trying to sell a Sportster-historica 11 y a price-sensitive model-for the cost of a Super Glide Big Twin, in a motorcycle marketplace hurt by a recession and high interest rates. To move the XR-1000s, dealers often had to discount them.

Given Harley-Davidson 's situation in the 1980s, one might justifiably wonder why the XR-1000 came to be at all. Though enthusiasts within H-D had long been lobbying for a bike like this, management’s highly leveraged 1981 buy-out from AMF had left Harley deeply in <iebt, short on cash and stuck in a flat market. Harley suffered huge losses in 1981 and 1982. Had its lenders cut off its overadvance at that point, the pompany could have been pompelled to file Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

TYPICAL ASKING PRICE FOR A USED XR-1000 TODAY IS AROUND $7500, BUT THE TREND IS UPWARD, WITH SOME SELLERS GETTING $10,000 FOR NICE SPECIMENS.

Yet management came to H-D Race Director Dick O’Brien in June of 1982 with the request to build the XR1000. Why? “They were trying to find something to throw into the picture that would be all-new and exciting. They wanted it quick,” O’Brien says, which explains why the race department was asked to develop the XR-1000, completing the task in an astounding 60 days. The line engineers were hard at work developing the next generation of Harley motors, the Evolution series, and had no time for a low-volume hybrid like the XR-1000.

For Clyde Fessler-then H-D’s marketing director and a figure central to the preation of the XR1000-the issue was morale and money. Fessier faced a dealer network sinking into paralysis. An exciting new motorcycle might get dealprs’ minds off the flat pconomy and H-D’s finanpial plight. If those dealers didn’t work at selling bikes, Harley was dead.

One source says that about 1500 XR1000s were delivered to dealers, though H-D has yet to provide official production figures. And even if it wasn’t a smash sales success, the XR-1000 did generate excitement among both riders and dealers, as intended. But the XR1000 was a limited means to a limited end. Certainly H-D planned to sell every one it made, but it didn’t intend to make many, or to make them for long. Had sales been stronger, the XR1000 might have remained in the line longer. But the bike couldn’t have remained without continued development-not when faced with the performance potential and streetability of the Evolution Sportsters. Harley-Davidson survived its fiscal battles; the XR-1000, a mere soldier and therefore expendable, did not. Production ceased in 1984, though some leftover models were sold as ’85s.

Road testers in 1983 lamented about what the XR-1000 was not, but for the most part, they liked it for what it was-a Sportster with more power, a competent chassis and excellent brakes. Some of the shortcomings testers mentioned were characteristic of Harleys in general and Sportsters in particular-overly large handgrips, minimal fuel capacity, stiff shifting and punishing vibration at certain speeds. But some of the compromises necessary to build the XR gave it shortcomings all its own.

One of these was a pronounced tendency of the bike to drift left, a result of an imbalance caused by the placement of a heavy exhaust system on the left side of the bike. To maintain a straight course, a rider had to apply slight-butconstant countersteering. The high pipes, which, despite a heat shield, could cook a rider’s left leg, and the dual carbs with their huge air cleaners also required a certain flexibility on the part of the rider. And you could forget about carrying a passenger. Sure, it was possible to mount a Sportster two-up saddle and, yes, the swingarm was drilled and tapped for passenger pegs. But unless your significant other was bow-legged and had asbestos riding pants, packing double was not an option.

In everyday street use, the XR-1000 is a higheffort bike and difficult to ride smoothly. Working the stiff clutch and stiffer throttle in stop-and-go traffic will try your muscles, and your patience, for there’s a lag between the time the throttle is turned and when the engine responds, which leads to a distinctly herky-jerky riding style.

The picture improves when you’re in top gear on a lightly traveled road. There, the XR-1000’s extra horsepower is noticeable-and enjoyable enough that the temptation to run the bike up is irresistible and constant. The XR seems to be happiest when accelerating hard. At steady and legal speeds, it exhibits what magazine road testers in California called “lean surge,” a condition caused by EPA-mandated air-fuel mixtures. Had those testers ridden an XR-1000 in Wisconsin, they might not have used such a generous phrase, for in temperatures below 70 degrees, the XR doesn’t just surge-it spits and pops like a bike with severe carburetion troubles.

Still, on a warm day, the XR-1000 is fun for backroad riding. Up to a point. Its suspension is more compliant than that of the XLCR Cafe Racer, but you needn’t comer as fast as a roadracer to discover that flexy forks and so-so shocks cause wallowing in spirited cornering. Cornering is more enjoyable if you use the XR’s excellent brakes to reduce your entrance speed and then get on the throttle early. The reward for this restraint is the marvelous push of a big, torquey

Twin and an equally marvelous thunder from the high pipes.

These sensations will make you feel something like a racer, but the standard Sportster ergonomics work against riding that way. Aggressive riding would feel much more natural with rearset foot controls like those on the XLCR, and with a lower and narrower handlebar-the kind of modifications made by people who roadraced the XR-1000.

In truth, whatever its reason for being, the XR-1000 was probably better suited to the track than to the street. Certainly, if H-D intended the XR1000 to be a streetbike rather than a racing machine in street clothes, you wouldn’t have known that from the advertising. In 1983, its debut year, the XR-1000 had its own brochure. On the outside the words “A new motorcycle. By the race people. For the street people,” were superimposed on a huge photo of the race-inspired engine. Inside, the copywriters missed no opportunity to make a connection with Harley’s racing heritage. The power of this bike would make us feel “like Jay Springsteen in street clothes.” And if we wanted to feel “like Jay Springsteen in leathers,” there were “three highperformance mod kits available to pound out up to 95 horsepower for closed-circuit riding.”

The brochure even included Harley-Davidson’s offer of contingency money for XR-1000 riders who took first place in any of the AMA-sanctioned Battle of the Twins classes.

In 1993, 10 years after its introduction, the XR-1000 is a bike not often seen on the street, as O’Brien himself has noted: “I don’t see any of them around hardly anymore. I don’t know where the hell they’re hiding them now.”

a of if to

its a I

Well, XR-lOOOs aren’t being hidden-they’re being bought and sold more than ridden. In his Illustrated Harley-Davidson Buyer ’s Guide, former Cycle World Editor Allan Girdler gives the XR-1000 a full four stars, as high as he rates any Sportster for investment purposes. As Girdler points out, “The factory probably won’t ever make a machine like this again.” Some people obviously figured this out a while ago, like the collector in Oregon who has 10 XR1000s for sale. Serious offers only.

How serious? The typical asking price for a used XR1000 today is around $7500-about what you’d have to pay to own a retired XR-750 racer-but the trend is upward, and some sellers are asking and getting more than $10,000 for especially nice specimens.

What most of us thought we wanted when the XR moved from mmor to reality was a racebike for the street. What we got was a streetbike that could be raced. It was more than a Sportster, but less than an XR-750.

Of course, any streetbike, no matter how narrowly focused, represents some compromises. Whether a street-going Harley XR750 that had endured the inevitable compromises on the way to production would have fulfilled our expectations is a question we will probably never have the chance to answer.

But that won’t keep us from asking for the bike we expected 10 years ago. □

HARLEYDAVIDSON SURVIVED ITS FISCAL BATTLES; THE XR-1000, A MERE SOLDIER ANE THEREFORE EXPENDABLE DID NOT