Beemer update

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

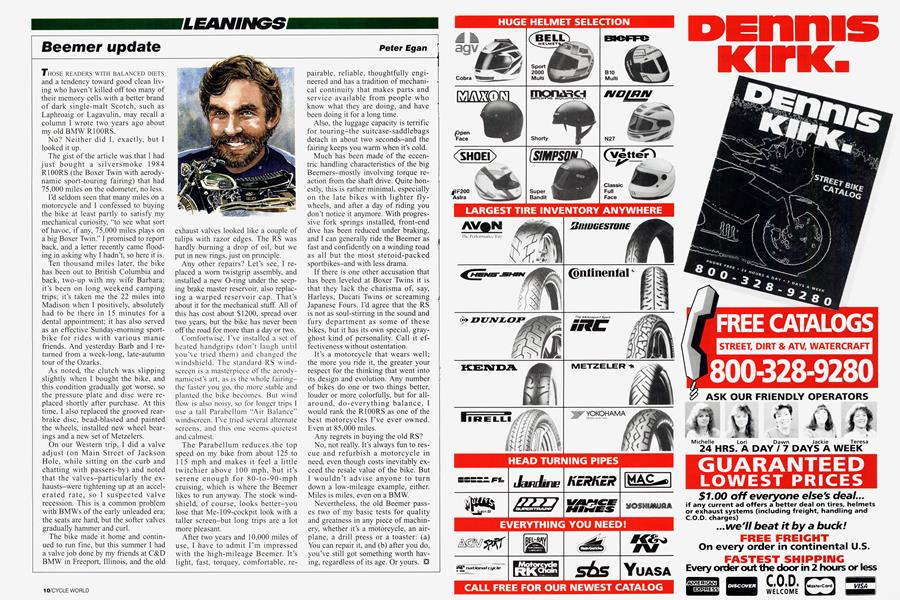

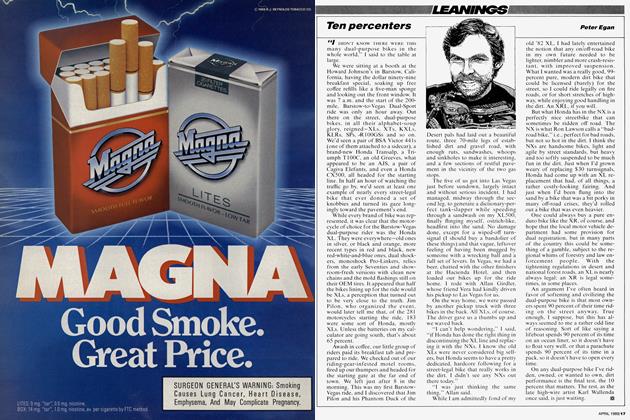

THOSE READERS WITH BALANCED DIETS and a tendency toward good clean living who haven’t killed off too many of their memory cells with a better brand of dark single-malt Scotch, such as Laphroaig or Lagavulin, may recall a column I wrote two years ago about my old BMW R100RS.

No? Neither did I, exactly, but I looked it up.

The gist of the article was that I had just bought a silversmoke 1984 R100RS (the Boxer Twin with aerodynamic sport-touring fairing) that had 75,000 miles on the odometer, no less.

I’d seldom seen that many miles on a motorcycle and I confessed to buying the bike at least partly to satisfy my mechanical curiosity, “to see what sort of havoc, if any, 75,000 miles plays on a big Boxer Twin.” I promised to report back, and a letter recently came flooding in asking why I hadn’t, so here it is.

Ten thousand miles later, the bike has been out to British Columbia and back, two-up with my wife Barbara; it’s been on long weekend camping trips; it’s taken me the 22 miles into Madison when I positively, absolutely had to be there in 15 minutes for a dental appointment; it has also served as an effective Sunday-morning sportbike for rides with various manic friends. And yesterday Barb and I returned from a week-long, late-autumn tour of the Ozarks.

As noted, the clutch was slipping slightly when I bought the bike, and this condition gradually got worse, so the pressure plate and disc were replaced shortly after purchase. At this time, I also replaced the grooved rearbrake disc, bead-blasted and painted the wheels, installed new wheel bearings and a new set of Metzelers.

On our Western trip, I did a valve adjust (on Main Street of Jackson Hole, while sitting on the curb and chatting with passers-by) and noted that the valves-particularly the exhausts-were tightening up at an accelerated rate, so I suspected valve recession. This is a common problem with BMWs of the early unleaded era; the seats are hard, but the softer valves gradually hammer and curl.

The bike made it home and continued to run fine, but this summer I had a valve job done by my friends at C&D BMW in Freeport, Illinois, and the old exhaust valves looked like a couple of tulips with razor edges. The RS was hardly burning a drop of oil, but we put in new rings, just on principle.

Any other repairs? Let’s see, I replaced a worn twistgrip assembly, and installed a new O-ring under the seeping brake master reservoir, also replacing a warped reservoir cap. That’s about it for the mechanical stuff. All of this has cost about $1200, spread over two years, but the bike has never been off the road for more than a day or two.

Comfortwise, I’ve installed a set of heated handgrips (don’t laugh until you’ve tried them) and changed the windshield. The standard RS windscreen is a masterpiece of the aerodynamicist’s art, as is the whole fairingthe faster you go, the more stable and planted the bike becomes. But wind flow is also noisy, so for longer trips 1 use a tall Parabellum “Air Balance” windscreen. I’ve tried several alternate screens, and this one seems quietest and calmest.

The Parabellum reduces the top speed on my bike from about 125 to 115 mph and makes it feel a little twitchier above 100 mph, but it’s serene enough for 80-to-90-mph cruising, which is where the Beemer likes to run anyway. The stock windshield, of course, looks better-you lose that Me-109-cockpit look with a taller screen-but long trips are a lot more pleasant.

After two years and 10,000 miles of use, I have to admit I’m impressed with the high-mileage Beemer. It’s light, fast, torquey, comfortable, repairable, reliable, thoughtfully engineered and has a tradition of mechanical continuity that makes parts and service available from people who know what they are doing, and have been doing it for a long time.

Also, the luggage capacity is terrific for touring-the suitcase-saddlebags detach in about two seconds-and the fairing keeps you warm when it’s cold.

Much has been made of the eccentric handling characteristics of the big Beemers-mostly involving torque reaction from the shaft drive. Quite honestly, this is rather minimal, especially on the late bikes with lighter flywheels, and after a day of riding you don’t notice it anymore. With progressive fork springs installed, front-end dive has been reduced under braking, and I can generally ride the Beemer as fast and confidently on a winding road as all but the most steroid-packed sportbikes-and with less drama.

If there is one other accusation that has been leveled at Boxer Twins it is that they lack the charisma of, say, Harleys, Ducati Twins or screaming Japanese Fours. I’d agree that the RS is not as soul-stirring in the sound and fury department as some of these bikes, but it has its own special, grayghost kind of personality. Call it effectiveness without ostentation.

It’s a motorcycle that wears well; the more you ride it, the greater your respect for the thinking that went into its design and evolution. Any number of bikes do one or two things better, louder or more colorfully, but for allaround, do-everything balance, I would rank the R100RS as one of the best motorcycles I’ve ever owned. Even at 85,000 miles.

Any regrets in buying the old RS?

No, not really. It’s always fun to rescue and refurbish a motorcycle in need, even though costs inevitably exceed the resale value of the bike. But I wouldn’t advise anyone to turn down a low-mileage example, either. Miles is miles, even on a BMW.

Nevertheless, the old Beemer passes two of my basic tests for quality and greatness in any piece of machinery, whether it’s a motorcycle, an airplane, a drill press or a toaster: (a) You can repair it, and (b) after you do, you’ve still got something worth having, regardless of its age. Or yours.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue