THE BIKES THAT MADE MILWAUKEE FAMOUS

HARLEY-DAVIDSON 90TH ANNIVERSARY ALL-STAR REVIEW

DAVID JOHNSON

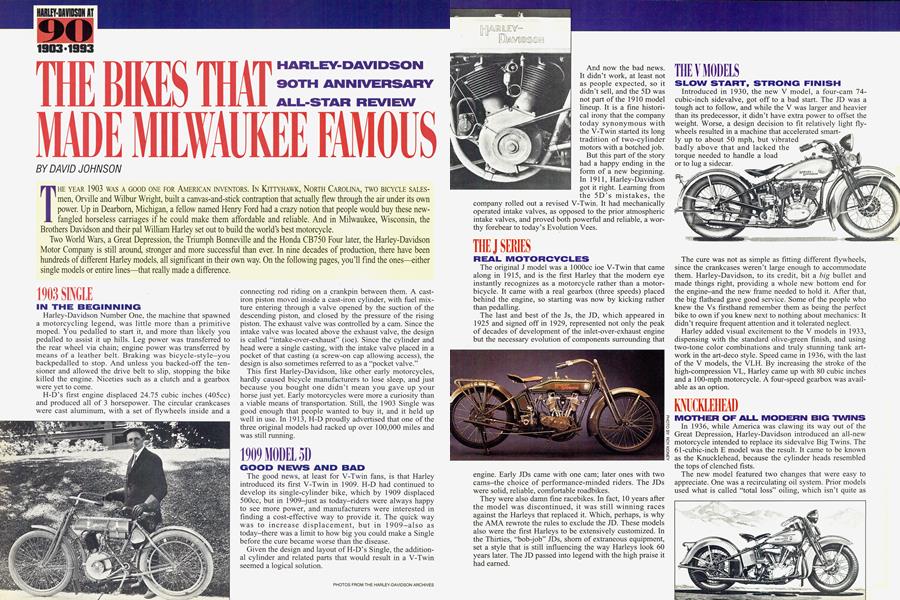

THE YEAR 1903 WAS A GOOD ONE FOR AMERICAN INVENTORS. IN KITTYHAWK, NORTH CAROLINA, TWO BICYCLE SALESmen, Orville and Wilbur Wright, built a canvas-and-stick contraption that actually flew through the air under its own power. Up in Dearborn, Michigan, a fellow named Henry Ford had a crazy notion that people would buy these new-fangled horseless carriages if he could make them affordable and reliable. And in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the Brothers Davidson and their pal William Harley set out to build the world's best motorcycle.

Two World Wars, a Great Depression, the Triumph Bonneville and the Honda CB750 Four later, the Harley-Davidson Motor Company is still around, stronger and more successful than ever. In nine decades of production, there have been hundreds of different Harley models, all significant in their own way. On the following pages, you'll find the ones-either single models or entire lines-that really made a difference.

1903 SINGLE IN THE BEGINNING

Harley-Davidson Number One, the machine that spawned a motorcycling legend, was little more than a primitive moped. You pedalled to start it, and more than likely you pedalled to assist it up hills. Leg power was transferred to the rear wheel via chain; engine power was transferred by means of a leather belt. Braking was bicycle-style—you backpedalled to stop. And unless you backed-off the tensioner and allowed the drive belt to slip, stopping the bike killed the engine. Niceties such as a clutch and a gearbox were yet to come.

H-D’s first engine displaced 24.75 cubic inches (405cc) and produced all of 3 horsepower. The circular crankcases were cast aluminum, with a set of flywheels inside and a

connecting rod riding on a crankpin between them. A castiron piston moved inside a cast-iron cylinder, with fuel mixture entering through a valve opened by the suction of the descending piston, and closed by the pressure of the rising piston. The exhaust valve was controlled by a cam. Since the intake valve was located above the exhaust valve, the design is called “intake-over-exhaust” (ioe). Since the cylinder and head were a single casting, with the intake valve placed in a pocket of that casting (a screw-on cap allowing access), the design is also sometimes referred to as a “pocket valve.”

This first Harley-Davidson, like other early motorcycles, hardly caused bicycle manufacturers to lose sleep, and just because you bought one didn’t mean you gave up your horse just yet. Early motorcycles were more a curiosity than a viable means of transportation. Still, the 1903 Single was good enough that people wanted to buy it, and it held up well in use. In 1913, H-D proudly advertised that one of the three original models had racked up over 100,000 miles and was still running.

1909 MODEL 5D GOOD NEWS AND BAD

The good news, at least for V-Twin fans, is that Harley introduced its first V-Twin in 1909. H-D had continued to develop its single-cylinder bike, which by 1909 displaced 500cc, but in 1909-just as today-riders were always happy to see more power, and manufacturers were interested in finding a cost-effective way to provide it. The quick way was to increase displacement, but in 1909-also as today-there was a limit to how big you could make a Single before the cure became worse than the disease.

Given the design and layout of H-D’s Single, the additional cylinder and related parts that would result in a V-Twin seemed a logical solution.

And now the bad news. It didn’t work, at least not as people expected, so it didn’t sell, and the 5D was not part of the 1910 model lineup. It is a fine historical irony that the company today synonymous with the V-Twin started its long tradition of two-cylinder motors with a botched job.

But this part of the story had a happy ending in the form of a new beginning. In 1911, Harley-Davidson got it right. Learning from the 5D’s mistakes, the the 5D’s mistakes, the company rolled out a revised V-Twin. It had mechanically operated intake valves, as opposed to the prior atmospheric intake valves, and proved both powerful and reliable, a worthy forebear to today’s Evolution Vees.

THE J SERIES REAL MOTORCYCLES

The original J model was a lOOOcc ioe V-Twin that came along in 1915, and is the first Harley that the modem eye instantly recognizes as a motorcycle rather than a motorbicycle. It came with a real gearbox (three speeds) placed behind the engine, so starting was now by kicking rather than pedalling.

The last and best of the Js, the JD, which appeared in 1925 and signed off in 1929, represented not only the peak of decades of development of the inlet-over-exhaust engine but the necessary evolution of components surrounding that

engine. Early JDs came with one cam; later ones with two cams-the choice of performance-minded riders. The JDs were solid, reliable, comfortable roadbikes.

They were also damn fine racebikes. In fact, 10 years after the model was discontinued, it was still winning races against the Harleys that replaced it. Which, perhaps, is why the AMA rewrote the mies to exclude the JD. These models also were the first Harleys to be extensively customized. In the Thirties, “bob-job” JDs, shorn of extraneous equipment, set a style that is still influencing the way Harleys look 60 years later. The JD passed into legend with the high praise it had earned.

THE V MODELS SLOW START. STRONG FINISH

SLOW START, STRONG FINISH

Introduced in 1930, the new V model, a four-cam 74cubic-inch sidevalve, got off to a bad start. The JD was a tough act to follow, and while the V was larger and heavier than its predecessor, it didn’t have extra power to offset the weight. Worse, a design decision to fit relatively light flywheels resulted in a machine that accelerated smartly up to about 50 mph, but vibrated badly above that and lacked the torque needed to handle a load or to lug a sidecar.

The cure was not as simple as fitting different flywheels, since the crankcases weren’t large enough to accommodate them. Harley-Davidson, to its credit, bit a big bullet and made things right, providing a whole new bottom end for the engine-and the new frame needed to hold it. After that, the big flathead gave good service. Some of the people who knew the Vs firsthand remember them as being the perfect bike to own if you knew next to nothing about mechanics: It didn’t require frequent attention and it tolerated neglect.

Harley added visual excitement to the V models in 1933, dispensing with the standard olive-green finish, and using two-tone color combinations and truly stunning tank artwork in the art-deco style. Speed came in 1936, with the last of the V models, the VLH. By increasing the stroke of the high-compression VL, Harley came up with 80 cubic inches and a 100-mph motorcycle. A four-speed gearbox was available as an option.

KNUCKLEHEAD MOTHER OF ALL MODERN BIG TWINS

In 1936, while America was clawing its way out of the Great Depression, Harley-Davidson introduced an all-new motorcycle intended to replace its sidevalve Big Twins. The 61-cubic-inch E model was the result. It came to be known as the Knucklehead, because the cylinder heads resembled the tops of clenched fists.

The new model featured two changes that were easy to appreciate. One was a recirculating oil system. Prior models used what is called “total loss” oiling, which isn’t quite as bad as it sounds: There was an oil tank and a pump delivering oil to the engine, and the rider had a hand pump to introduce extra oil if riding conditions required it. The oil would remain in the engine until it was burned up or leaked out. This system was fine if the mechanical pump and the rider were both in sync with how the bike was being used, not so fine if they weren’t. The other important change was the use of overhead valves, a more efficient design than the sidevalve, which meant more power.

Despite some teething problems, the Knuckle soon became a success. And in engineering terms, it was the branch on H-D’s evolutionary tree from which all subsequent Big Twins sprang-from Panhead in 1948 to Shovelhead in 1966 to Blockhead (Evolution) in 1984.

Look at any modem Big Twin and you can still see the Knucklehead’s tear-drop fuel tank. Look at any Softail model and you can still see the lines of its rigid frame. And look at the Softail Springer and you can see a modem version of its leading-link front fork.

THE 45 LITTLE HARLEY THAT COULD

The W series 45, in over five decades of production, fulfilled more roles with less development than anything else in the H-D family tree. A 750cc sidevalve V-Twin first produced in 1929, the 45 (for 45 cubic inches) was a basic, utilitarian machine for the solo rider, but it became many other things.

In 1932 a three-wheeled version was released. The ServiCar, as this trike was called, functioned as a delivery vehicle, a service-station runabout and a traffic-control cop-cycle. When the AMA attempted to make racing more affordable by creating the C Class in the mid-1930s, the 45 became a racer. With the onset of WWII, the 45 became a military vehicle. It was fitted with a skidplate, a luggage rack, a fork scabbard for guns, an oil-bath air cleaner and blackout lights.

In its roles as commercial vehicle, racebike and military vehicle, the 45 earned a reputation as a bike that did the job, day in and day out. The two-wheeled 45 disappeared in 1952, but the Servi-Car persisted until 1974. And the little

Twin did more than earn its place in history: It fathered the 45-cubic-inch sidevalve K Model, which begat the 55cubic-inch sidevalve KH, which begat the 55-cubic-inch overhead-valve Sportster.

K MODEL THE FLATHEAD'S LAST STAND

In many ways the K model was a direct consequence of WWII. The war had put a lot of young men in contact with English motorcycles, which were quite different in conception from home-market Indians and Harleys. The Britbikes were more sporting-smaller and lighter, with hand clutches and foot shifting.

Rather than compete head-to-head with the British, Harley-Davidson decided to take a different approach, essentially crossing the sporting concept of a British Twin with the rugged reality of its V-Twins. The result, in 1952, was a remarkably modem motorcycle with light telescopic fork, swingarm rear suspension, foot shifter and hand-operated clutch.

Its 750cc engine was a curious mix of old and new. The old part was that it was a sidevalve, essentially an update of

the W series 45. The new part was that it was of unit construction; the transmission no longer existed in a case separate from the engine.

The other old part was that the K was slow-at least for the kind of sporting motorcycle it appeared to be. So in 1954, displacement was bumped up to 55 cubic inches and the K became the KH, which was still not terribly fast. This is odd, because H-D clearly knew how to make flatheads fly. The racing version of the K, the KR, was competitive in flat-track and roadracing into the late 1960s.

At any rate, Harley had more than one cure for the K’s street-performance deficit. One was the KHK of 1955, which included the cams, valves and some other massaging developed for the racing KR. The other was the KL, a radical new engine that never reached production. But the cure that “took” came in 1957, in the form of the overhead-valve XL Sportster models.

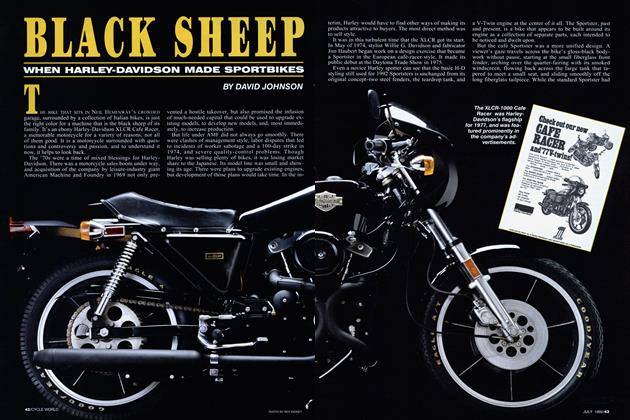

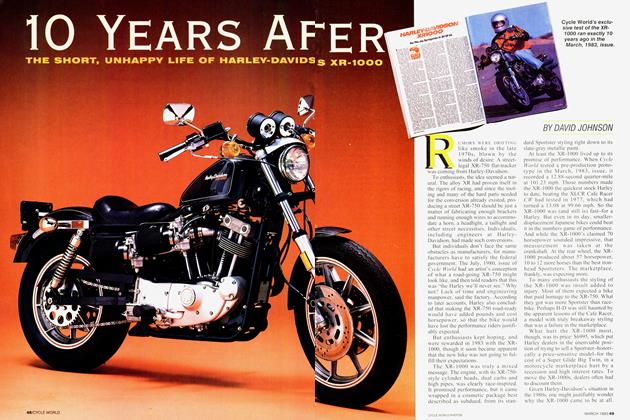

XLCH KING SPORTSTER

Yes, the Sportster was introduced in 1957, but that first one still wore K Model styling: It looked like a scaled-down version of H-D’s Big Twin touring machines. The bike that to this day personifies the Sportster came along a year later in 1958. With its solo saddle, staggered-dual exhaust and signature small gas tank, the CH was a V-Twin motorcycle distilled to its essence. It was also a genuine superbike in its day, and even into the late 1960s; many ended up on the racetrack in competition.

In 1972, the Sportster was enlarged to lOOOcc, and in the ensuing years H-D occasionally tried to reshape the Sportster as a touring bike (the 1977 XLT), as a Euro-style café racer (the 1977 XLCR), as a cruiser in Big Twin style (the 1979 XLS) and as a quasi-racer hot rod (the 1983 XR1000). But, as Coca-Cola discovered, when an original becomes a classic, you better leave it alone. Which is why when the Sportster was bom again in Evolution form for 1986, it came first at the original displacement of 883cc and with the spartan, single-seat styling of the 1958 CH.

Though Sportsters no longer sell on performance, that spare CH style is as popular today as it was in the beginning. And in an odd twist of fate, the 883 Sportster is again a competition machine, with classes all its own on both pavement and dirt.

ELECTRA GLIDE KING Of THE HIGHWAY

Some background first. In 1949, one year after the Knucklehead engine evolved into the Panhead, a hydraulically dampened telescopic fork replaced Harley’s leadinglink fork. With that change came a name: Hydra-Glide. When the Hydra-Glide discovered rear suspension in 1958, it got a new name: Duo-Glide, perhaps the shortest possible

way of saying it had hydraulically damped suspension front and rear. In 1965, something new was added to the mix-electric starting-and with that came a new label: Electra Glide. The kick-start pedal was still there, for those who had the need or the inclination, but the die was cast. With an increasing emphasis on comfort and convenience, the Electra Glide gained weight and bulk, and was locked into the role of tourer.

The Electra Glide got a new top end in 1966, and the engine came to be called the Shovelhead. But that was not the end of the changes. An alternator replaced the 12-volt generator in 1970, a fiberglass handlebar fairing and rear tote box (Tour-Pak in Harley-speak) appeared in 1971, a front disc brake in 1972, a rear disc brake in 1973.

The final version of the old-style FLH Electra Glide in 1984, which looked and worked pretty much like its predecessors from the 1970s, had a solidly mounted 80-cubicinch Shovelhead engine, belt final drive and a larger Tour-Pak. By then it was no match for the touring bikes from Japan, or even for Harley’s own mbber-mount FLT, but the Electra Glide will be fondly remembered by many riders as the original King of the Highway.

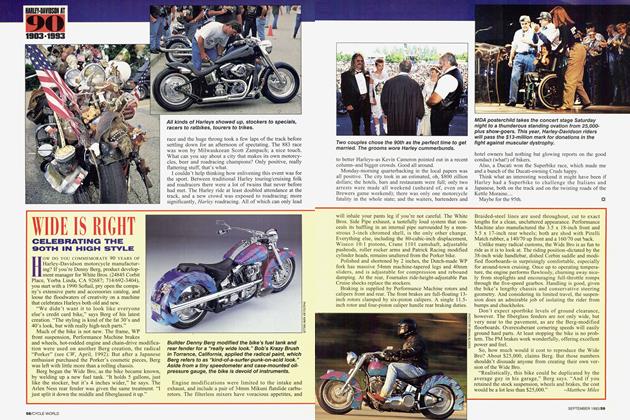

1971 SUPER GLIDE THE CHOPPER GOES CORPORATE

While the first Super Glide, as a motorcycle, was not remarkable, its effects continue to be felt.

In the simplest terms, the FX was a stripped-down Electra Glide. It dispensed with the Glide’s huge battery and electric starter in favor of a small battery and kickstarter; footboards were replaced with footpegs; a 3.5-gallon tank took up residence in place of the tourer’s 5-gallon tank; and instead of the dual exhausts of the dresser, the Super Glide used the single exhaust fitted to police bikes. But the most apparent changes were at front and back: The front wore a Sportster fork assembly, and out back there was a fiberglass seat-fender combination, not so lovingly referred to by some observers as the “boat-tail.”

Strictly speaking, this wasn’t a chopper. In spirit, it was a

bob-job, the less-is-more kind of machine that people who liked big-bike power without big-bike bulk started building in the 1930s. But to H-D, the idea of building a model that might be seen as a chopper-the kind of bike outlaws rode-was scary indeed and a major leap of faith. With the Super Glide began Harley’s careful walking of the line between the motorcycle as outdoor fun and the motorcycle as personal statement with an edge of rebellion.

With the Super Glide, Harley also more fully realized that it could create new models by mixing parts and changing cosmetics. Thus, that first Super Glide gave birth to numerous variants, some of which are landmarks in their own right-the Low Rider, the Sturgis, the Wide Glide. The ability to generate numerous models from a single powertrain was perhaps a genius bom of necessity, but to this day no one does it more or better than H-D.

Most importantly, with the Super Glide H-D created not just a new kind of Harley, but a new class of motorcycle: the cmiser.

XR750 LIVING LEGEND

The XR750 flat-tracker you see in your mind’s eye-the one with the huge, finely finned aluminum cylinders, the dual carbs and filters stretching back along the right side, and the twin high pipes running along the left-was not the way the first XR750 looked.

What the first XR750 engine looked like was an early Sportster engine-which, in a way, it was. Why? Because the rules of Class C racing, which originated in the 1930s, changed in a big way in 1968. Gone was the previous 750cc sidevalve/500cc overhead-valve formula, replaced by a class based only on a 750cc displacement limit. The change didn’t immediately render Harley’s flathead KR racer uncompetitive, but the handwriting was on the wall. The change came too suddenly for Harley to respond with a truly new design, so the racing department destroked the iron-barrelled, 883cc XLR Sportster engine, squeezed it into the KR frame, and had a racer for the 1970 season.

Except that it was down on power. And it broke. So in 1970 and 1971, the national championships went to British bikes.

The iron XR had been viewed from the start as a stop-gap model. In 1972, the XR was reborn in all alloy form, and that’s

the bike we all see when we think of the XR750. It returned the national number-one plate to H-D in 1972, and in the 21 years since then, it’s won too many victories to list here. There were downs along the way-when Honda finally got its flattrack V-Twin right and took several championships-but today, as in 1972, the XR750 is the benchmark, the bike to beat.

1980 TOUR GLIDE SOMETHING OLD, SOMETHING NEW

Evolution or revolution? For H-D, the choice has not been based upon a set of abstract principles argued in a vacuum. Financial conservatism and a knowledge of its market’s resistance to new ideas has caused Harley to carefully control the pace of change. That’s why an old engine ends up in a new chassis, or why a new engine starts out in an old chassis. Tradition is the spoonful of sugar that helps the medicine of change go down.

The 1980 Tour Glide (FLT in H-D shorthand) followed this formula, but had a lot more medicine than sugar. The bodywork, including a frame-mounted fairing, was new. The five-speed transmission was new. The fully enclosed drive chain was new. The chassis was new-to accommodate a rubber powertrain-mounting system that allowed the engine to shake to its heart’s content without those vibrations troubling the rider or destroying the bike’s components. Only the engine was familiar: the 80-cubic-inch Shovelhead.

Traditionalists were a bit put off, but to riders who wanted a Harley touring bike that worked better than the FLH, the FLT was good medicine. It was smooth and it handled-not just compared to the Electra Glide but to the best that Japan had to offer-and people who wouldn’t have considered a Harley before were interested. The FLT sent a message that H-D was serious about bringing the function of its motorcycles up to date.

THE SOFTAILS HAPPY DAYS ARE HERE AGAIN

If you were building a chopper in the ’60s or ’70s, you might have started with a stock 1950-something HydraGlide, extended the fork, fitted a narrow 21-inch front wheel, bobbed the rear fender, and fitted a fender-hugging stepped saddle. And you would have ended up with something that looked pretty much like the 1984 Softail.

What set the Softail apart from Harley’s other street customs was its frame, which-at least in terms of style-took a giant leap backward, to the time when Harleys had no rear suspension beyond what an underinflated 16-inch tire provided. But this new frame did have suspension-a swingarm, actually, designed to look like a rigid rear section, with shock absorbers mounted unobtrusively below the transmission and working in extension rather than compression.

The frame was a stroke of genius. But H-D’s genius was not in inventing it-they didn’t. An independent engineer by the name of Bill Davis did. Harley’s genius was in reading the winds of change, which were blowing in the direction of retro-style, and then in having the courage to ride the wind at a time when being wrong could have spelled financial

ruin. That retro-styling hit new heights in 1986 when the Heritage Softail debuted, looking for all the world like a 1949 Hydra-Glide that had escaped from a museum.

The Heritage Softail Classic, fitted with old-style leather saddlebags and windshield, is perhaps the most complete expression of nostalgia ever mass produced. And it will remain so until H-D again follows the lead of the aftermarket and marries its leading-link front end with a 1940s-style valanced front fender to yield a Heritage Softail Springer Classic, at which point the resemblance to the 1936 Knucklehead will be inescapable. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

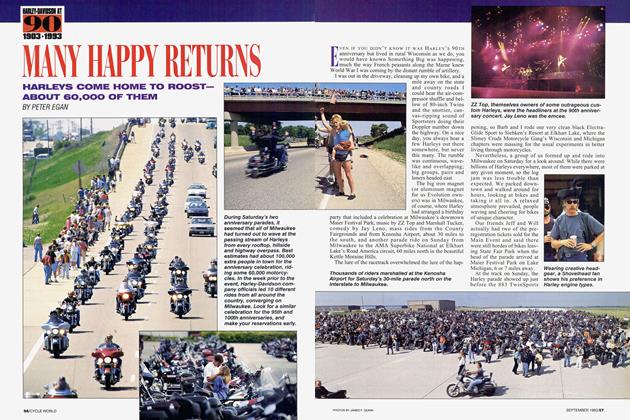

Up Front

Up FrontTomb of the Unknown Harleys

September 1993 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsDo Loud Pipes Save Lives?

September 1993 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCVicious Cycles

September 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupBmw Sings A Song of Singles

September 1993 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupPick A Pair of Yamaha 600s

September 1993