The Last Indian

UP FRONT

David Edwards

IT’S A CHARACTER FLAW, I’M SURE. LIKE the little boy who’s always finding stray dogs, I attract oddball motorcycles in need of a good home. I just can’t seem to help myself.

As already chronicled on these pages, I own a 1946 Velocette GTP 250, a two-stroke model even most Velo experts don’t know about. I’ve also got one of 750 made-in-Schenectady Yankee Zs, a 1972 dual-purpose 500 powered by two OSSA cylinders mounted atop a common crankcase. My 1960 MV Agusta TREL 125 is another seldom-seen model. And a few issues back, I detailed my 1976 Paul Dunstall Honda, a CB750 Four cloaked in the English cafe king’s sporty bodywork. In that column, I also casually mentioned I was on the lookout for a Gilera Bicilindrica 300 and a 1970 Indian Enfield.

Well, I now have the Indian.

Never heard of a 1970 Indian Enfield? Don’t feel bad; virtually nobody else has, either, but it was the last great endeavor of one Mr. Floyd Clymer. If you know Clymer at all it’s probably from the hundreds of automobile and motorcycle manuals the company that still bears his name prints. Or perhaps you remember him as the publisher of Cycle, which he purchased in 1953. Never one to shy away from shameless self-promotion, he blurbed his inaugural issue “Floyd Clymer’s New Cycle Magazine. More Photos! Better Paper! More News!” He ran the magazine until 1967, when he sold out at a handsome profit.

But there was more to the man than publishing. Born in Colorado in 1895, Clymer was captivated by motorcycles and by the entrepreneurial spirit at an early age. With support from his doctor father, he started selling Thomas Auto-Bi motorcycles at age 12. By 1914, he was a successful 19-year-old Excelsior and Harley-Davidson dealer in Greeley, his hometown. Soon he moved to Denver, billed himself as the “Largest Motorcycle Dealer in the West” and became the Indian, Excelsior and Henderson distributor for Colorado and neighboring states. During this time, Clymer also made a name for himself as a racer, winning the first professional Pikes Peak hillclimb and numerous dirt-track events. As part of the Harley-Davidson factory team in 1916, he took an eightvalve V-Twin to a new world record, covering 100 miles in 1 hour, 11 minutes, an average of 83.6 mph.

Ever the wheeler-dealer, Clymer sold his motorcycle interests to form an automobile accessories company, then a California-based publishing house. Late in life, after selling off Cycle, he returned to his roots, promoting national-class races, becoming the Western-states distributor for Royal Enfield, the sole U.S. importer of the German Münch Mammoth and acquiring the trademark rights to the Indian logo, out of circulation since the Massachusetts company’s demise in the late Fifties. It’s not for nothing that in 1969 Cycle affectionately called Clymer, then in his early 70s, the “King of the Hucksters.”

OF Floyd’s dream was to build a latter-day Indian cafe-racer powered by an updated 750cc Sport Scout V-Twin and housed in a downsized version of the Mammoth chassis. Friedei Münch cobbled together one prototype in 1968. To raise funds for production, the Floyd Clymer Motorcycle Division sold three Indian minibike models-the Papoose, the Ponybike and the Boy Racer-and two full-size streetbikes, one powered by a Velocette 500cc Single, the other by Royal Enfield’s 750cc Series II Interceptor vertical-Twin. Both the Clymer Velo and Enfield had a handsome, distinctly Italian air, with frames and suspension from chassis specialist Leo Tartarini, Borrani alloy rims, Pirelli tires and massive Grimeca 2LS front brakes. Incongruously, the fuel tanks were finished in trendy two-tone candy colors, but with the old-timey Indian script logo plastered on their sides.

In his Illustrated Indian Buyer’s Guide, historian Jerry Hatfield notes that 250 of the 1969-70 Indian Velos were produced, while perhaps less than 10 of the Indian Enfields made it off the assembly line. (Hatfield incorrectly refers to these as Norton-powered, probably because by that time financially troubled Enfield had been taken over by the Norton-Villiers group.)

More Indian Enfields might have been manufactured if not for the fact that Clymer keeled over at his desk signing papers one morning early in 1970, a fitting way for the King of the Hucksters to shuffle off this mortal coil.

After Clymer’s death, his widow sold the Indian trademark to a Tiawanese minibike-maker, setting in motion a furor over the rights to the name that hasn’t yet subsided (see Roundup, this issue). Until (if) that dispute is settled, then, the Clymer/Tartarini/Enfield cross-breed remains as the last of the full-size Indians.

Anyway, shortly after the issue mentioning my desire for a ’70-model Indian Enfield hits the newsstands comes a nice telephone call from Steven Schleimer. He has one-no jokes about Schleimer’s Clymer, please-do I want it? Despite a severely depleted bank account, I do. Some horse-trading involving an old Honda XL500 ensues; this, plus a minor misappropriation from a home-improvement landscape loan (is self-embezzlement a punishable crime?) and the Indian Enfield is all mine. Its frame is bent, the mufflers are rusted through, the aluminum is oxidized, the paint is dulled, the engine needs a complete rebuild, and where the money will come from for the restoration, Buddha only knows.

Besides funding, one of the challenges of restoring oddball bikes is that there is little printed material available and few experts to turn to. So, if you have an Clymer Indian Enfield, know someone involved in the bike’s manufacture or have parts (especially a left sidecover), contact me c/o the magazine; I’d love to talk with you.

One more thing. If you have a Gilera 300 for sale, please don’t call.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

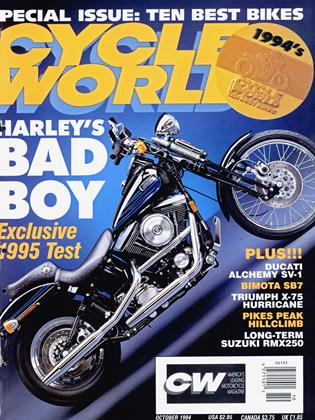

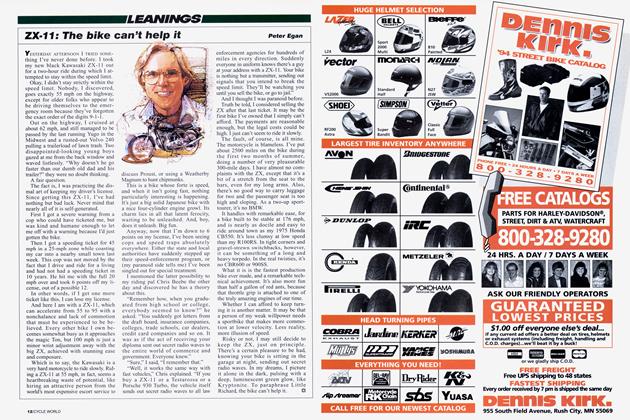

Leanings

LeaningsZx-11: the Bike Can't Help It

October 1994 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCGrace In Hardware

October 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1994 -

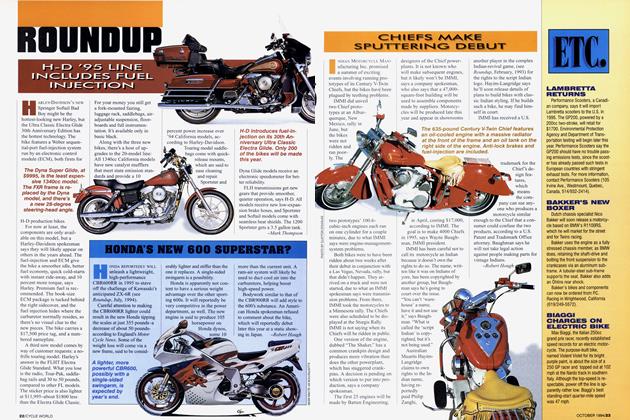

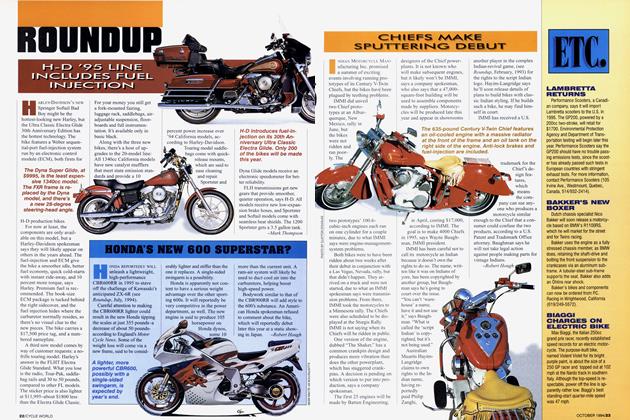

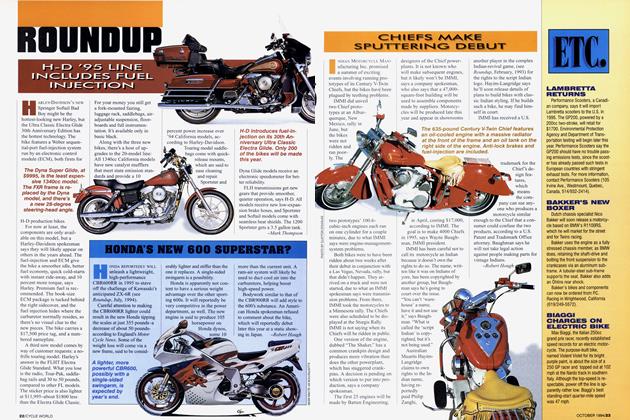

Roundup

RoundupH-D `95 Line Includes Fuel Injection

October 1994 By Mark Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupHonda's New 600 Superstar?

October 1994 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupChiefs Make Sputtering Debut

October 1994 By Robert Hough