ZX-11: The bike can't help it

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

YESTERDAY AFTERNOON I TRIED SOMEthing I’ve never done before. I took my new black Kawasaki ZX-ll out for a two-hour ride during which I attempted to stay within the speed limit.

Okay, I didn’t stay strictly within the speed limit. Nobody, I discovered, goes exactly 55 mph on the highway, except for older folks who appear to be driving themselves to the emergency room because they’ve forgotten the exact order of the digits 9-1-1.

Out on the highway, I cruised at about 62 mph, and still managed to be passed by the last running Yugo in the Midwest and a rusted-out Volvo 240 pulling a trailerload of lawn trash. Two disappointed-looking young boys gazed at me from the back window and waved listlessly. “Why doesn’t he go faster than our dumb old dad and his trailer?” they were no doubt thinking.

A fair question.

The fact is, I was practicing the dismal art of keeping my driver’s license. Since getting this ZX-ll, I’ve had nothing but bad luck. Never mind that nearly all of it is self-generated.

First I got a severe warning from a cop who could have ticketed me, but was kind and humane enough to let me off with a warning because I’d just gotten the bike.

Then I got a speeding ticket for 45 mph in a 25-mph zone while coasting my car into a nearby small town last week. This cop was not moved by the fact that I drive and ride for a living and had not had a speeding ticket in 10 years. He hit me with the full 20 mph over and took 6 points off my license, out of a possible 12.

In other words, if I get one more ticket like this, I can lose my license.

And here I am with a ZX-l l, which can accelerate from 55 to 95 with a nonchalance and lack of commotion that must be experienced to be believed. Every other bike I own becomes somewhat busy as it approaches the magic Ton, but 100 mph is just a minor wrist adjustment away with the big ZX, achieved with stunning ease and composure.

Which is to say, the Kawasaki is a very hard motorcycle to ride slowly. Riding a ZX-ll at 55 mph, in fact, seems a heartbreaking waste of potential, like hiring an attractive person from the world’s most expensive escort service to discuss Proust, or using a Weatherby Magnum to hunt chipmunks.

This is a bike whose forte is speed, and when it isn’t going fast, nothing particularly interesting is happening. It’s just a big solid Japanese bike with a nice four-cylinder engine growl. Its charm lies in all that latent ferocity, waiting to be unleashed. And, boy, does it unleash. Big fun.

Anyway, now that I’m down to 6 points on my license, I’ve been seeing cops and speed traps absolutely everywhere. Either the state and local authorities have suddenly stepped up their speed-enforcement program, or (my paranoid side tells me) I’ve been singled out for special treatment.

I mentioned the latter possibility to my riding pal Chris Beebe the other day and discovered he has a theory about this.

“Remember how, when you graduated from high school or college, everybody seemed to know?” he asked. “You suddenly got letters from the draft board, insurance companies, colleges, trade schools, car dealers, credit card companies and so on. It was as if the act of receiving your diploma sent out secret radio waves to the entire world of commerce and government. Everyone knew.”

“Sure,” I said, “I remember that.” “Well, it works the same way with fast vehicles,” Chris explained. “If you buy a ZX-l l or a Testarossa or a Porsche 930 Turbo, the vehicle itself sends out secret radio waves to all law enforcement agencies for hundreds of miles in every direction. Suddenly everyone in uniform knows there’s a guy at your address with a ZX-11. Your bike is nothing but a transmitter, sending out signals that you intend to break the speed limit. They’ll be watching you until you sell the bike, or go to jail.”

And I thought I was paranoid before.

Truth be told, I considered selling the ZX after that last ticket. It may be the first bike I’ve owned that I simply can’t afford. The payments are reasonable enough, but the legal costs could be high. I just can’t seem to ride it slowly.

The fault, of course, is all mine. The motorcycle is blameless. I’ve put about 2500 miles on the bike during the first two months of summer, doing a number of very pleasurable 300-mile days. I have almost no complaints with the ZX, except that it’s a bit of a stretch from the seat to the bars, even for my long arms. Also, there’s no good way to carry luggage for two and the passenger seat is too high and sloping. As a two-up sporttourer, it’s no BMW.

It handles with remarkable ease, for a bike built to be stable at 176 mph, and is nearly as docile and easy to ride around town as my 1975 Honda CB550. It’s less clumsy at low speed than my R100RS. In tight corners and gravel-strewn switchbacks, however, it can be something of a long and heavy torpedo. In the real twisties, it’s no CBR600 or 900SS.

What it is is the fastest production bike ever made, and a remarkable technical achievement. It’s also more fun than half a gallon of red ants, because that throttle grip is attached to one of the truly amazing engines of our time.

Whether I can afford to keep turning it is another matter. It may be that a person of my weak willpower needs a sportbike that makes more commotion at lower velocity. Less reality, more illusion of speed.

Risky or not, I may still decide to keep the ZX, just on principle. There’s a certain pleasure to be had, knowing your bike is sitting in the garage at night, sending out secret radio waves. In my dreams, I picture it alone in the dark, pulsing with a deep, luminescent green glow, like Kryptonite. To paraphrase Little Richard, the bike can’t help it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Last Indian

October 1994 By David Edwards -

TDC

TDCGrace In Hardware

October 1994 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1994 -

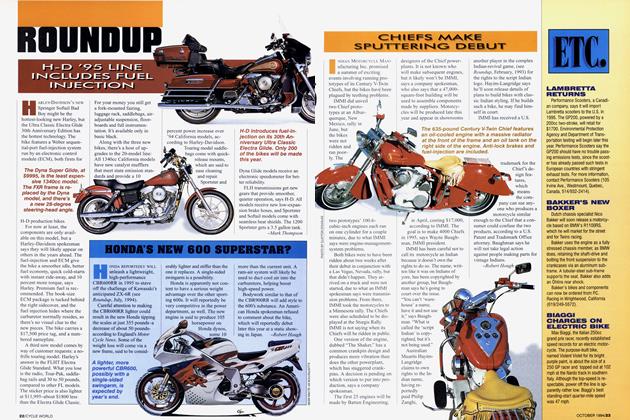

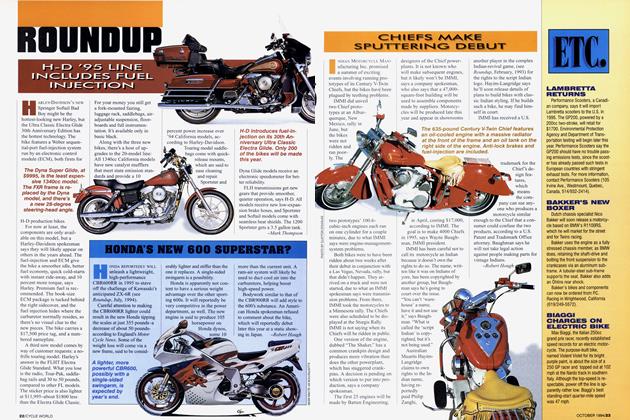

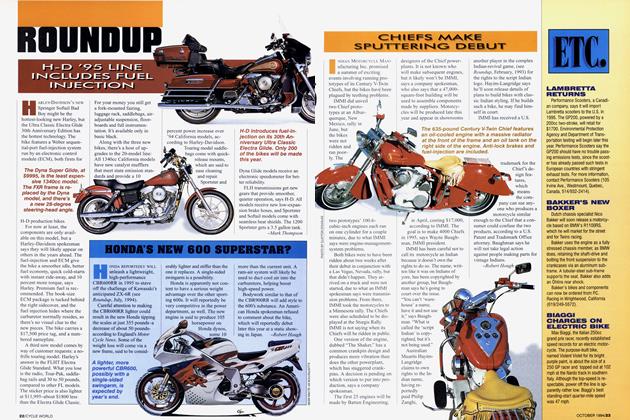

Roundup

RoundupH-D `95 Line Includes Fuel Injection

October 1994 By Mark Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupHonda's New 600 Superstar?

October 1994 By Robert Hough -

Roundup

RoundupChiefs Make Sputtering Debut

October 1994 By Robert Hough