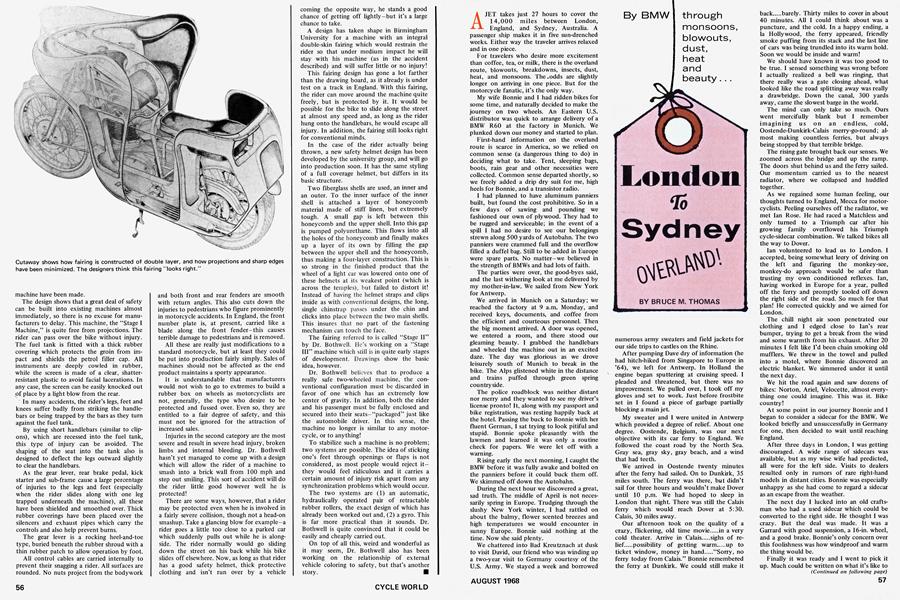

London To Sydney OVERLAND!

through monsoons, blowouts, dust, heat and beauty...

BRUCE M. THOMAS

A JET takes just 27 hours to cover the 14,000 miles between London, England, and Sydney, Australia. A passenger ship makes it in five sun-drenched weeks. Either way the traveler arrives relaxed and in one piece.

For travelers who desire more excitement than coffee, tea, or milk, there is the overland route, blowouts, breakdowns, insects, dust, heat, and monsoons. The odds are slightly longer on arriving in one piece. But for the motorcycle fanatic, it's the only way.

My wife Bonnie and I had ridden bikes for some time, and naturally decided to make the journey on two wheels. An Eastern U.S. distributor was quick to arrange delivery of a BMW R60 at the factory in Munich. We plunked down our money and started to plan.

First-hand information on the overland route is scarce in America, so we relied on common sense (a dangerous thing to do) in deciding what to take. Tent, sleeping bags, boots, rain gear and other necessities were collected. Common sense departed shortly, so we freely added a drip dry suit for me, high heels for Bonnie, and a transistor radio.

I had planned to have aluminum panniers built, but found the cost prohibitive. So in a few days of sawing and pounding we fashioned our own of plywood. They had to be rugged and serviceable; in the event of a spill I had no desire to see our belongings strewn along 500 yards of Autobahn. The two panniers were crammed full and the overflow filled a duffel bag. Still to be added in Europe were spare parts. No matter—we believed in the strength of BMWs and had lots of faith.

The parties were over, the good-byes said, and the last withering look at me delivered by my mother-in-law. We sailed from New York for Antwerp.

We arrived in Munich on a Saturday; we reached the factory at 9 a.m. Monday, and received keys, documents, and coffee from the efficient and courteous personnel. Then the big moment arrived. A door was opened, we entered a room, and there stood our gleaming beauty. I grabbed the handlebars and wheeled the machine out in an excited daze. The day was glorious as we drove leisurely south of Munich to break in the bike. The Alps glistened white in the distance and trains puffed through green spring countryside.

The police roadblock was neither distant nor merry and they wanted to see my driver's license pronto! It, along with my passport and bike registration, was resting happily back at the hotel. Passing the buck to Bonnie with her fluent German, I sat trying to look pitiful and stupid. Bonnie spoke pleasantly with the lawmen and learned it was only a routine check for papers. We were let off with a warning.

Rising early the next morning, I caught the BMW before it was fully awake and bolted on the panniers before it could buck them off. We skimmed off down the Autobahn.

During the next hour we discovered a great, sad truth. The middle of April is not necessarily spring in Europe. Trudging through the slushy New York winter, I had rattled on about the balmy, flower scented breezes and high temperatures we would encounter in sunny Europe. Bonnie said nothing at the time. Now she said plenty.

We chattered into Bad Kreutznach at dusk to visit David, our friend who was winding up a two-year visit to Germany courtesy of the U.S. Army. We stayed a week and borrowed numerous army sweaters and field jackets for our side trips to castles on the Rhine.

After pumping Dave dry of information (he had hitch-hiked from Singapore to Europe in '64), we left for Antwerp. In Holland the engine began sputtering at cruising speed. I pleaded and threatened, but there was no improvement. We pulled over, I took off my gloves and set to work. Just before frostbite set in I found a piece of garbage partially blocking a main jet.

My sweater and I were united in Antwerp which provided a degree of relief. About one degree. Oostende, Belgium, was our next objective with its car ferry to England. We followed the coast road by the North Sea. Gray sea, gray sky, gray beach, and a wind that had teeth.

We arrived in Oostende twenty minutes after the ferry had sailed. On to Dunkirk, 35 miles south. The ferry was there, but didn't sail for three hours and wouldn't make Dover until 10 p.m. We had hoped to sleep in London that night. There was still the Calais ferry which would reach Dover at 5:30. Calais, 30 miles away.

Our afternoon took on the quality of a

crazy, flickering, old time movie in a very

cold theater. Arrive in Calais sighs of relief possibility of getting warm.....up to

ticket window, money in hand "Sorry, no

ferry today from Calais." Bonnie remembered the ferry at Dunkirk. We could still make it back barely. Thirty miles to cover in about

40 minutes. All I could think about was a puncture, and the cold. In a happy ending, a la Hollywood, the ferry appeared, friendly smoke puffing from its stack and the last line of cars was being trundled into its warm hold. Soon we would be inside and warm!

We should have known it was too good to be true. I sensed something was wrong before I actually realized a bell was ringing, that there really was a gate closing ahead, what looked like the road splitting away was really a drawbridge. Down the canal, 300 yards away, came the slowest barge in the world.

The mind can only take so much. Ours went mercifully blank but I remember imagining us on an endless, cold, Oostende-Dunkirk-Calais merry-go-round; almost making countless ferries, but always being stopped by that terrible bridge.

The rising gate brought back our senses. We zoomed across the bridge and up the ramp. The doors shut behind us and the ferry sailed. Our momentum carried us to the nearest radiator, where we collapsed and huddled together.

As we regained some human feeling, our thoughts turned to England, Mecca for motorcyclists. Peeling ourselves off the radiator, we met Ian Rose. He had raced a Matchless and only turned to a Triumph car after his growing family overflowed his Triumph cycle-sidecar combination. We talked bikes all the way to Dover.

Ian volunteered to lead us to London. I accepted, being somewhat leery of driving on the left and figuring the monkey-see, monkey-do approach would be safer than trusting my own conditioned reflexes. Ian, having worked in Europe for a year, pulled off the ferry and promptly tooled off down the right side of the road. So much for that plan! He corrected quickly and we aimed for London.

The chill night air soon penetrated our clothing and I edged close to Ian's rear bumper, trying to get a break from the wind and some warmth from his exhaust. After 20 minutes I felt like I'd been chain smoking old mufflers. We threw in the towel and pulled into a motel, where Bonnie discovered an electric blanket. We simmered under it until the next day.

We hit the road again and saw dozens of bikes: Norton, Ariel, Velocette, almost everything one could imagine. This was it. Bike country!

At some point in our journey Bonnie and I began to consider a sidecar for the BMW. We looked briefly and unsuccessfully in Germany for one, then decided to wâit until reaching England.

After three days in London, I was getting discouraged. A wide range of sidecars was available, but as my wise wife had predicted, all were for the left side. Visits to dealers resulted only in rumors of rare right-hand models in distant cities. Bonnie was especially unhappy as she had come to regard a sidecar as an escape from the weather.

The next day I lucked into an old craftsman who had a used sidecar which could be converted to the right side. He thought I was crazy. But the deal was made. It was a Garrard with good suspension, a 16-in. wheel, and a good brake. Bonnie's only concern over this foolishness was how windproof and warm the thing would be.

Finally it was ready and I went to pick it up. Much could be written on what it's like to (Continued on following page) ride a combination for the first time. Let me say only that it's an experience.

We headed back to Dover the next morning after I snapped up the top to completely enclose Bonnie in the sidecar. There she sat, grinning in her windproof, waterproof contraption. Communication was impossible. I felt sorry for myself all the way to Dover. Especially when it started to rain.

Breezing into the ferry booking office, I requested tickets to Calais. "Sorry, friend," came the reply, "No boats to Calais today." I thought, here we go again! It turned out that French workers were showing general displeasure of their government by a one-day, nationwide strike. The English operated Dover-Boulougne ferry was running, however.

Moving quickly down the poplar-lined roads of northern France, we reached Paris and turned east to Strasbourg. It was raining off and on. Off Bonnie and on me that is.

We re-entered Munich and set about getting spare parts and having the rear drive pinion ratio lowered for sidecar use. My choice of what spares to carry was hardly imaginative. I settled for two sets of cables, bulbs, gaskets, wire (electrical and baling), tape, nuts and bolts, and a grab bag of other items. In London I had purchased two Avon tires, one 16-in. for the sidecar and one 18-in. for the bike, and two tubes for each. After adding extra patch kits I figured the machine was well set for road wear. We considered carrying a spare piston, rings, and valve springs, but decided against it as the bike was new.

We left Munich and aimed south for Australia. In hilly, wet, winding country we approached the Alps and Gross Glockner Pass. Crossing was delayed an hour while a recent snow was cleared. The trip up and over was through swirling, spitting snow, the road cutting between 12-ft. walls of white.

Twisting down from the pass proved a sidecar brake is necessary and there is such a season as spring! Beautiful green valleys unfolded. Picturesque Alpine villages appeared along with rushing, sparkling, mountain streams. A deer paused obligingly for pictures. Bonnie put down the canvas top and we became reacquainted after our cold weather separation. We drove through the sunshine into Italy.

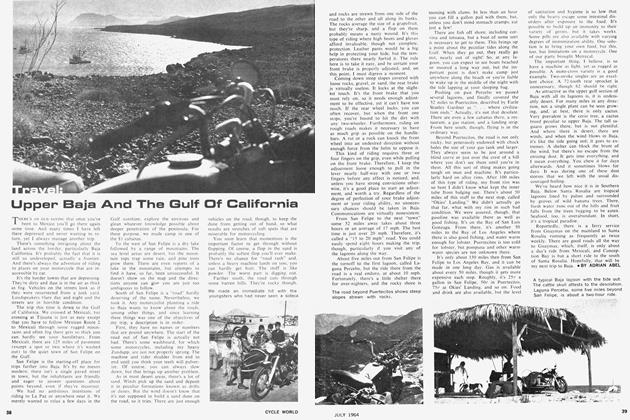

From Trieste our route led to Rijeka, Yugoslavia, and down the twisting, well-paved road by the Adriatic Sea. Slower than the freeway which rolls through the middle of Yugoslavia to Greece, the coastal route is far more scenic. The only drawback is the dozens of German tourists who rocket around the curves pulling large, swaying, camping trailers. When meeting or passing one of these monsters, I sorely missed the acceleration and maneuverability of a solo machine.

After resting a while in the old, walled city of Dubrovnik, we prepared for our first ordeal by road. The coast road runs smoothly down through Albania to Greece. But the Albanian government isn't welcoming American tourists at the moment. Cursing politicians, we set off to circle the forbidden land and join the freeway at Skopje.

First on the obstacle course was a mountain range crossed by what can only be called an improved goat path. Pavement was nonexistent. Any motorist who reaches the summit deserves more than the sign which greets him in English with, "Congratulations! You have just completed 31 switchbacks to reach the top of Mt. Lovcen Pass. 4871 feet!" As if every one of those switchbacks wasn't im-

pressed for life on aching muscles.

Darkness caught us halfway down the other side and nobody's going to drive that road for the first time at night. We slept two feet off the road, pressed close to the sheer rock wall, and were often thundered fearfully awake by madmen who courted death by grinding their trucks down that mountain in the dark.

The next. day saw us bouncing toward Skopje on a Detroit torture test track; potholes, football sized rocks, with an inch of fine dust. Ten mph was tops and Bonnie became a jack-in-the-box popping up and down in the bucking sidecar. Meeting the good road to Greece was like entering the Pearly Gates.

The army had just taken over the government in Greece, but it had no effect on us as tourists in Athens. It did, however, mean more business for the army dispatch riders who scurried around the sun drenched city on their WW II tank shift Harley-D avid sons.

We finally departed from Athens, heading north again, then turning for the road to Istanbul. This is the part of Europe where most people traveling overland funnel together for their crossing into Asia. We shared the road with scores of young people in Land Rovers, Jeeps, converted ambulances, old trucks, and even an ex-taxi from London.

For the overlander, Istanbul provides the first real taste of the East. A city of 1000 minarets, it offers sights, sounds, and smells that dazzle the senses. One can spend days exploring its crowded streets and bustling bazaars.

Having met an Australian couple in a little Austin car, we joined forces and drifted down the western coast of Turkey to Izmir and beyond. These were pleasant days, filled with fine food, fine weather, and friendly people. We were off the beaten path and the hospitality offered by the villagers was fantastic. On leaving, we often had to refuse armsfuL of food because there was simply no more room to carry it.

On the way up to Ankara we had our first flat and our second an hour later. The last one tore the tire badly so the spare Avon was put on. I wasn't allowed to lift a finger during these stops. Passing Turks insisted on changing the tires and patching the tubes out of friendship.

At the capital city of Ankara we checked in at a BP (British Petroleum) Mocamp. These affairs feature a camp ground, showers, gas stoves for cooking, and a small grocery. After camping by the road for a few weeks, the Mocamp seemed plush.

Overlanders traveling by vehicle usually stop at the Mocamp s where the latest gossip and road information is batted around. In this way we learned the need of a carnet de passage to continue our journey. "A what?" I asked. A carnet, I was told, is a document issued after the assessed value of the vehicle has been placed in bond with a bank. If the vehicle is subsequently sold in Iran, for example, the government there claims the money in bond. This is to deter people from selling vehicles on the black market in countries which place high taxation on imported foreign vehicles.

Naturally we had no interest in selling our outfit on the black or any other market, but try and convince some minor embassy official of that! The Iranian consul told us flatly; "No admittance without a carnetV

Discouraged, we drove back to the Mocamp, only to find it awash after a heavy

downpour; clothes and sleeping bags floated in 4 in. of water and were as soggy as our spirits.

The next day a young Englishman arrived, traveling alone on a 1953 Triumph 650. He was bound for Karachi, Pakistan, where he would board ship for Australia. He was very shy and only weighed about 130 lb. Bonnie was certain he would be eaten by buzzards on the Iranian desert route he had chosen. But having worked as a motorcycle mechanic, he was quietly confident and knew what he was doing; a damn sight better than we did....^e had a carnet\

I spent a few days picking at the carnet problem and tightening nuts. Then one day, we heard that familiar sound. Into camp pulled a 1959 BSA 650 with bright red Avon fairing. "England to Australia" was lettered boldly across it. Wow! Our kind of people! Colin Irons and Tony Willis dismounted and we soon became fast friends. They were young British seamen who decided to reach Australia by land for a change. And, they had no carnet either! We quickly compared notes. They had been told in London that no carnet was really needed for motorcycles. Together we revisited the Iranian Embassy. And, so help me, in the very same room we were told one wouldn't be needed.

Deciding to cross our bureaucratic bridges as they came, we shoved off the next morning in good cheer.

That afternoon, Tony and Cohn were crossing a wooden bridge when their front wheel slipped between two planks. The BSA lurched into a post which broke, but prevented them from plunging to the river bed below. The heavily laden bike fell over, throwing Tony clear but dragging Cohn underneath. Both lads were badly cut and shaken. Colin's foot, already swelling, was thought to be badly sprained.

Almost a week was spent getting through Turkey. The road, leading by the Black Sea, then over the mountains to Ezerum, was a poor dirt affair, its loose, gravelled surface making balance difficult. The sidecar was an advantage here. Though we carried some of our friends' luggage, the going was rough for them. Cohn couldn't stand on his foot and Tony had to wear socks over his raw palms while driving, but neither complained.

A bright spot occurred one afternoon as we were bouncing along. Raising a cloud of dust were two approaching motorcycles. We all bounced to a stop. When the dust settled we shook hands with two Australians who had shipped their 250-cc Jawas to Bombay and from there were heading overland to London.

They gave us some first hand, discouraging information on the roads ahead. We offered the encouraging news that they were only two days away from the pavement that began in Ankara. The two mentioned they were going to work for two years in London, then return to Australia. "By bike?" I asked, still enthusiastic and naive. The Aussies, bearded, dirt covered, eyes weary, looked at me with tolerance. "No, mate, BOAC for us!"

Crossing the mountains, we careened towards Ezerum in eastern Turkey. A particularly bad bump snapped one of the two main sidecar fittings and we ground to a halt, sagging like an old sofa. Whipping out 50 ft. of Dacron rope, I lashed the break together, and we limped into Ezerum. The BSA's rear fender, bearing the full weight of their panniers, had crumpled under the pounding and was taking greedy bites out of the rear tire.

We sought out a mechanic and in two hours a new fitting, machined to order, graced the sidecar and simple but strong braces cured the BSA. The total bill was $1.80. We were so overjoyed that we agreed to his request of driving the machines briefly. Off he roared, first on the outfit then on the BSA, scaring us considerably, but no doubt upping his community standing by being seen on two such machines in one afternoon.

Reaching the Iranian border was a relief as it meant another country. The road to Teheran offered the usual surface with one basic difference. Now the dust, rocks, gravel, and potholes were laid on a surface patterned after the roughest washboard grandmother ever used. The regularity of the ripples set up terrific vibrations no matter what speed we drove. Our windshield shattered into a dozen pieces and lay behind in the road. Blowouts and punctures were becoming routine.

In Tabriz we purchased a tire for the BSA and more tubes for both machines. We took our change in more patches. Thus fortified, we made it to Mayana where we ran into one of the village children. Literally.

For the overland motorist, children are a problem in the Middle East. Some are fond of throwing rocks at passing vehicles. While this anti-social group never managed to hit us, from our curses you'd have thought they had. Worse is the youngsters' penchant for running into the road even after seeing an approaching vehicle. The kid in Mayana did just this, was clipped by the BSA's fairing.

Advice is if the tourist hits anyone or anything, keep going—if not out of the country, then straight to the nearest Embassy. That's easier said than done, thinking the way we do about hit and runs. Besides, a cop on a donkey could have overtaken our overloaded, low geared caravan. We stopped. The inevitable crowd gathered and the lengthy wrangling, so incomprehensible to the Western mind, began. What to do? Get the police. Who will go? Not the persons involved. The villagers bicker endlessly and and wring their hands. On and on and on while the boy still lies injured in the sun.

Two hours later Bonnie and I were allowed to leave and get the police. We led them back to the scene. The crowd had become ugly and Tony and Cohn were relieved to see us, and really relieved to see the police! More questions and reports followed. Finally, after four hours, the boy was put in a passing car and we all went to the police station.

Tony, the driver, was held, but we were free to leave. Naturally we did not go without him. Colin called the British Embassy in Teheran. The Consul was out. The police wanted money. The doctor wanted money. We offered to make one lump payment, but were not guaranteed Tony's freedom even then. We spent the night in jail with him, believing there is strength in numbers.

The next morning a judge freed Tony on payment of 1000 Rials ($14) which went to the boy's mother. Considerably relieved, we departed for Teheran. Reaching the British Embassy there was like regaining one's sanity. The Consul, ready to leave for Mayana, was amazed to see us. He explained that usually the driver is held until the injury heals, then the money claims begin. The Embassy can do nothing but try and obtain better food for the prisoner.

We found a hotel and lay down, exhausted. There was a heat wave in Teheran and 184

cases of food poisoning were reported. Bonnie, Tony, and Colin were three of them. I somehow escaped, and went with Colin to the Embassy doctor for medicine. The doctor noticed him limping and X-rayed his foot, "sprained" two weeks before. It was broken. A plaster cast was recommended. "We're not staying long enough for that," said Cohn. He rewrapped the bandage, collected the medicine, and hobbled out. We left.

The heat was still terrific and numerous stops were required to cool the engines. Twenty miles from the Caspian Sea a tremendous clatter erupted from our right cylinder. Pulling in the clutch, jamming on the brakes, all I could think of was a broken rod.

Stripping that cylinder was one of the great depressing moments of my life. The head came off to reveal a shattered exhaust valve seat. I couldn't believe it, but for proof the pieces were lying in my hand. Both the piston and the head itself were badly pitted. Misery and gloom. Removing the pushrods from the damaged cyhnder, I nursed the injured machine along to the next little town.

The lone cycle shop dealt only with small displacement bikes of obscure origin and his stock of spare parts could be held in one hand. None, needless to say, were for BMWs. "No matter," he seemed to say (no English), "let's have a look." While I sat, planning to hitch back to Teheran and wire for parts from Munich, he farmed the head out to a nearby machine shop, the cyhnder barrel to someone else, and happily set to work on the piston itself. A new seat was machined, inserted and ground (though hardly to BMW specifications). The piston was smoothed and the barrel certified useable. Assembly took little time and at dusk I kicked it over. Back from the grave! It spit compression at me from a handful of places and lacked much of its old power but it sure beat hitching back to Teheran! The total bill for that day was $4.40, and included some minor work on the BSA. The mechanic was so happy that we were happy that he took us all home for the night and blew his new profits on a chicken dinner that swelled our grateful stomachs.

In Iran, the roads were thoroughly depressing. Ahead of us lay 560 miles to the Afghanistan border. Soon we were resting once every hour from the pounding, then every 45 minutes. During these breaks we made a sadistic game of seeing who could first discover new damage to his machine.

What really broke our hearts was watching the new superhighway being built adjacent to our hellish route. We made grim jokes about describing the trip to our children who would yawn and say "Come on Dad, it couldn't have been that bad!" as they mounted their superbikes for a fast two-week ride to Australia.

A full day's ride usually took us about 130 miles. Knocking off 150 brought congratulations all around. We slept in Gendarmeries, the Iranian equivalent to our State Police barracks. These compounds were useful as they provided an escape from the inevitable crowds that gathered every time we stopped in a populated area. The people were friendly, but excessively so, crowding, shoving, touching, and endlessly repeating their three stock English phrases, "What is your name? Where do you come from? Where are you going?"

We left Iran in late afternoon after checking out with the Army, customs, police, and the secret police. Naturally the four offices are in distant parts of the town. Oh, yes. There was one more check at the actual border 8 miles away. There, returning our passports, the official stared at our machines and us. "You must be crazy," he offered. "Couldn't agree with you more, mate," snapped Cohn, "Open the gate!" He did, and we were in the mile-wide "no man's land" between the defined borders of Iran and Afghanistan.

Afghanistan.

This road, ignored by the maintenance crews (if such things exist) of both countries, featured sharp rocks that stuck up through the surface like daggars. We could have made it faster on foot, but at the end lay Afghanistan, the promised land for the overland motorist with its new Russianand U.S.-built highways. First, there were 80 miles of desert to cross. (Continued on page 91)

Entering Afghanistan is like turning back the centuries. Turbaned men wearing baggy outfits ride by on haughty camels. Women are rarely seen. The few visible are covered with heavy veils. Weird, walled towns of undetermined age sit at distances off the road and have no visible means of entry. We passed the night on the floor of a mud walled Afghan tea house in the middle of the desert.

Ten miles out of Herat, a solitary figure approached, trailing a cloud of dust. It was another Australian and a fellow BMW rider. His bike was new and shiny. He was dustless and fresh as though he'd just stepped out of an ad for Barbour jackets. We couldn't have been more the opposite. "Hello, mates," he said. "What lies ahead?" We laughed mirthlessly and told him. Slowly his grin faded.

We started off for Kandahar the next day at noon. We assumed an easy run on the Russian-built, two-lane concrete highway. We had forgotten the heat. Not a tree or rock breaks the sun on that stretch of desert. Camels stand simmering in the heat. Not another vehicle was seen for three hours. Our engines were like blast furnaces. The gallon of water we had brought was being rapidly consumed.

The heat was unbearable. If stopping helped the engines, it failed to relieve us. Mirages played tricks on our vision. At 4 p.m. we reached a roadside hotel. Miraculously, it had a swimming pool.

A hotel thermometer, placed on the road at 2 p.m. had registered 137 degrees. We had been stupid and lucky. A breakdown or flat in that heat would have invited sunstroke or heat exhaustion.

We spent the next day at the hotel, unwilling to leave the pool, and being a little afraid of the road. The hotel itself was insane. Built by the Russians in Hilton style, it contained about 100 rooms. Rent was 50 cents a night. The huge, thoroughly modern and completely equipped kitchens were spotless and unused-the simple menu was prepared in a mud hut out back.

At 3 a.m. we left again for Kandahar trying to beat the sun. That infernal afternoon had finished the rings in my right cyliner. I tailgated a friendly Land Rover for three days and 500 miles to Kabul, attempting to cut wind resistance and ease strain on the engine.

Kabul is a popular stopping place for overlanders mainly because they're half dead when they get there and its 5000-ft. altitude provides a cool climate in which to cure physical and/or mechanical ills. I longed for a BMW dealer and regretted my choice of spare parts. On stripping the cylinder, the rings had completely crumbled out in my hand.

After considerable searching, I found an old Russian auto whose rings looked similar to BMWs. They weren't, but with a little filing they fit and we were off again. Efficiency was dropping with each of these repairs and top speed was now 40 mph.

We were delayed while the Indian Embassy told us how awful we were for not having a carnet. Finally, after a week of bureaucratic stalling, we were issued entry permits for the bikes, and were off for the Khyber Pass.

Entering Pakistan via the Khyber is exciting. On maps, this area is marked "Tribal Territory" which means the Pakistani government has little authority there. An occasional column of troops is sent in to remind the tribesmen that other people have weapons as well but the Khyber population is left largely to its own devices. And these devices are guns. Every man, from the soft drink seller at the border, to the fierce, old, turbaned fighters of the villages, is armed to the teeth.

govern(Contlnued on page 92)

The pass is closed to traffic after 4 p.m. Brigands rule the area after dark. We did a lot of smiling and waving in those parts. To our knowledge no tourist has been bothered recently, but it is said that 3000 murderers reside along that stretch of road.

Camping that night at Peshawar, we awoke to find our large tire pump had been stolen. This we considered a serious loss as all handbooks on motoring through India warn of punctures galore. Both hand pumps for the BSA and BMW had packed up weeks ago from excessive use.

We were now on the Grand Trunk Road which runs from the Khyber Pass all the way to Calcutta, India, our destination, 1400 miles away. It is paved but narrow. It teems with traffic, most of it on foot. Having crossed deserted country for so long, running into such competition was a shock. Also new was the Monsoon, a trick of nature designed to thoroughly soak travelers.

India is truly unique. If we thought Pakistani roads were crowded, India is the big league! The road swarms with birds, chickens, dogs, pigs, donkeys, Indians, water buffalos, camels, elephants, slow moving carts, and sacred cows. The human population of India is approximately 500 million persons. Every one of them lives ON the Grand Trunk Road.

After a while we developed a technique for negotiating especially crowded areas. Closing up tight, the lead bike would hold steady on the horn and we would blast through the towns, hopefully close enough together that the curious wouldn't step between.

As we entered the capital city of Delhi, an unusually severe monsoon rain crashed down and flooded the streets with up to 3 ft. of water. Finding a high spot (only a foot deep) we could only wait it out as crates and furniture floated by.

After leaving Delhi the monsoon rains became worse and our progress was like a trials course over, or rather through, flooded and washed out roads. We stuck to the patented underwater procedure of slipping the clutch and keeping the revs high enough to blow water out of the mufflers.

Motorcycling in that country is not all cursing at pedestrians and scraping off rust. Between times, we explored a sampling of India's cultural treasures and met many of its people. Seeing the Taj Mahal was worth all the rain. We found it to be far more beautiful than its photographs.

One advantage of a motorcycle was that its openness enabled us to see and almost touch the fantastic variety of animal life that fills the roadsides-6-ft. tall cranes, wild monkeys, and flocks of multi-colored parrots.

We left our bikes in Benares, the Hindu holy city on the Ganges, and took a train to Nepal for two weeks of relaxation high in the Himalayan foothills. We chose not to drive because the rains had rendered roads to the north in even worse condition than those on which we had been traveling.

Back in India we reclaimed our bikes and set out for Calcutta, 425 miles away. In our absence the Ganges had risen even higher and the Grand Trunk Road was under 4 ft. of water. Returning to Benares, we shipped the bikes and ourselves to Calcutta by train.

Greater Calcutta is a city of some 8 million people, an estimated 2 million of whom are homeless, living and dying in the streets. Traffic consists of wheezing Indian homemade taxis, cars, and trucks, animal drawn carts, and a goodly portion of the 8 million Indians themselves. Local motorcyclists are provided with 350-cc Royal Enfields made under franchise in Madras.

We now faced the problem of where to go. For unknown (to us at least) reasons, Burma issues only 24-hour visas to travelers. And Mike Hailwood couldn't drive through Burma in 24 hours, even if the roads had been improved since the end of World War II, which they hadn't. We could ship the bike to Malaysia and drive up to Bangkok or ship it straight to Sydney, our final destination. We chose the latter, having been on the road seven months and learning that shipping schedules in southeast Asia were badly disrupted by the closing of the Suez Canal. Tony and Colin, being seamen, began to hunt for work on a ship bound for Australia.

Vowing to have a real party when we met up in Sydney, Bonnie and I left our companions and flew to Rangoon, then Bangkok. We soon drifted down to Singapore and got passage on a ship to Australia. Claiming our BMW on the dock in Sydney was like meeting an old friend.

Having gotten over the novelty of being able to have good food, soft beds, and even beer when we wanted them, we started thinking about the advice we could have used when planning our trip. For what they're worth, here are a few paragraphs:

1) Travelers need a passport with visas, vaccination certificate, driver's license, insurance (in Europe), and a title for the vehicle. Get the visas before leaving if possible. Keep these documents in order and up to date!

2) Get a carnet de passage, if the trip is to extend beyond Europe. While the trip can be done without one, having it will save much time and energy wasted in bickering and pleading with officials.

3) Use good sense in selecting tools and spare parts. I would stress extra tubes, a supply of patches, a sturdy pump, enough spare nuts and bolts to get you through Iran, and an extra air cleaner (I shook the Sahara out of mine every other night). While we made the whole trip on the original cables and bulbs there's no guarantee anyone else will. Tires are available in most places, but cost varies and quality may be poor. For every Avon and Dunlop there are six obscure brands. We carried a socket wrench and five heads to fit all BMW bolts. While this added some weight, it saved much valuable time.

Know your bike well! If a weak part is suspected, take a spare. Our mechanical troubles were unusually severe. Most bikes have made the trip with only a puncture or two at the worst. But be prepared. Breakdowns will probably occur miles from any formal repair shop. Be flexible in your thinking and get the machine running again no matter how crazy the method of repair.

Continued on following page)

If a breakdown occurs, take advantage of the iocal mechanics wherever possible. While their shops may appear ill equipped, they are original thinkers and can do wonders with their limited facilities.

4) Select a reliable, sturdy bike. Though we met a chap who did the trip on a Honda Trail 90, we wouldn't recommend it (neither would he). A heavy bike is a nuisance in the extremely slow, darting traffic of Eastern cities. But the machine must be able to cruise at speed for hundreds of miles through the desert and its heat.

5) Take enough money. While Tony and Colin made it from London to Calcutta on $140 each, that's cutting it close. Europe is relatively expensive. Assuming that you're camping, figure a minimum of $5 per day. I know there's a book around that says you can sleep in hotels as well for that amount, but remember there are gasoline, oil, and repairs to worry about.

East of Greece, $3 per day will get you by. I recommend upping these figures to deal with emergencies and delays.

6) Take care in regard to food and water. About four of five overlanders suffer some form of dysentery. Try to be the one that doesn't! Americans have the reputation abroad of being super scared to consume anything not boiled or purified. This is absurd and deprives the taste buds of fantastic local delicacies.

Carry a small first aid kit and a selection of pills. Take something for an upset stomach.

Get a prescription for some good, allpurpose antibiotic capsules such as Tetracyclin. These can fix anything from dysentery to infection from cuts. The East is ridden with germs to which the Westerner is especially susceptible. Don't be a hypochondriac, but if something is wrong with you, get it fixed pronto! That stomach trouble may be dysentery which can lead to hepatitis very quickly. Some anti-malaria pills are a good bet as well.

7) Travel lightl That favorite cardigan and transistor radio increase strain on the engine. Give the bike a break. A light, strong pair of gloves and a medium weight sweater for Europe are handy. For outerwear, Bonnie and I used Barbour jackets and recommend them highly.

If we had it to do again, we'd leave the sidecar behind. The experience of having it was fun, but we felt the lack of maneuverability was a drawback in crowds and on bad roads. But for all the rain and troubles, the trip itself was fantastic! In our worst moments we wouldn't have traded our outfit for two jet plane tickets.

A motorcycle acts as a magnet for people. If this at times was a nuisance, it was also the key to meeting hundreds of friendly people, which was the purpose of the trip.

While thousands of young English, Europeans, and Australians have traveled overland, relatively few Americans have set out on this route. Give it some thought. If you enjoy a challenge, take some time, save a little money, and GO! And if you want more laughs, tears, and experiences, take a motorcycle when you do.

Would we do it again? At the moment we're enjoying good food, soft beds, and air conditioned cocktail lounges. But, well-this sort of thing gets in your blood. ■