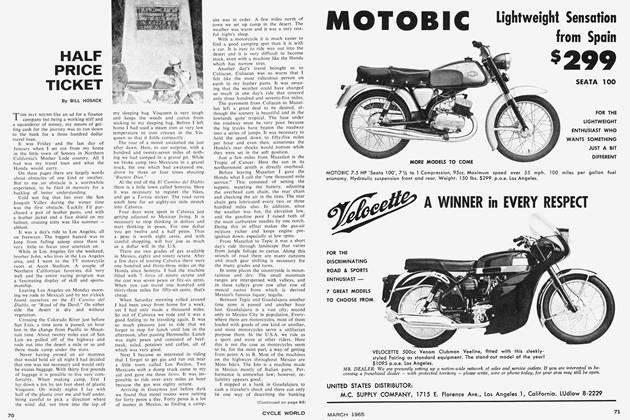

WILD SLICKROCK

Motorcycles to Another World in Canyonland, Utah

DICK WILSON

ONLY IN SELECT areas of the world can a person participate in the sport of slickrocking.

Slickrocking via motorcycle can be wild; it can be, and is, hazardous, and only for the adventurer, for the frontiersman who enjoys the rugged out-of-doors.

The terrain of southeastern Utah is a jumble of rocks-not sharp rocks, such as are found in the arid deserts of the southwestbut rocks that are exposed in compact layers. Erosion has uncovered these layers of sandstone in certain areas along the middle Colorado River, and the weathering of the strata is such that no other place in the world can compare with it.

In and around Canyonlands National Park and Arches National Monument in southeastern Utah, and stretching on to the southwest along the Colorado River, through the area of newly-created Lake Powell and on to Page, Ariz., are vast areas where nature has carved beautiful fantasies in the rock.

Some of the most intriguing and satisfying cycle riding is to be found in these wild, untamed and unspoiled wildernesses-which will some day be discovered by hordes of people. Right now, these amazing regions are for the most part inaccessible, except to the rough-and-tumblers who don’t mind picking their way along dusty jeep trails.

There are specific layers of rock that are especially appealing to a cyclist-strata that the geologists call the Navajo and the Kayenta sandstone. These layers have been eroded into extensive 50-mile-long pavements that undulate and roll-soft appearing rock that resembles whipped cream or marshmallow-yet it’s rock, pure sandstone, almost as hard as concrete.

One of these slickrock areas, and the one most easily accessible at the present time, begins within a half-mile of Moab, Utah, only a few miles from the Colorado border. This area is easily reached by U.S. 160 from either the north or south at any time of year. Other more extensive slickrock areas can be reached by traveling toward the shores of Lake Powell on poor roads which are fine for those who like to see the rougher parts of the country.

The Moab slickrock areas lie between Arches National Monument and Canyonlands National Park, the latter of which is only four years old and still unknown even to thousands. West of the small but modern city of Moab, a vast new area of slickrock has been opened up by uranium exploration within the past two months and is still virtually unexplored, except by early-day cowboys of the region who had a narrow, precipitous trail to the plateau on which the slickrock is found.

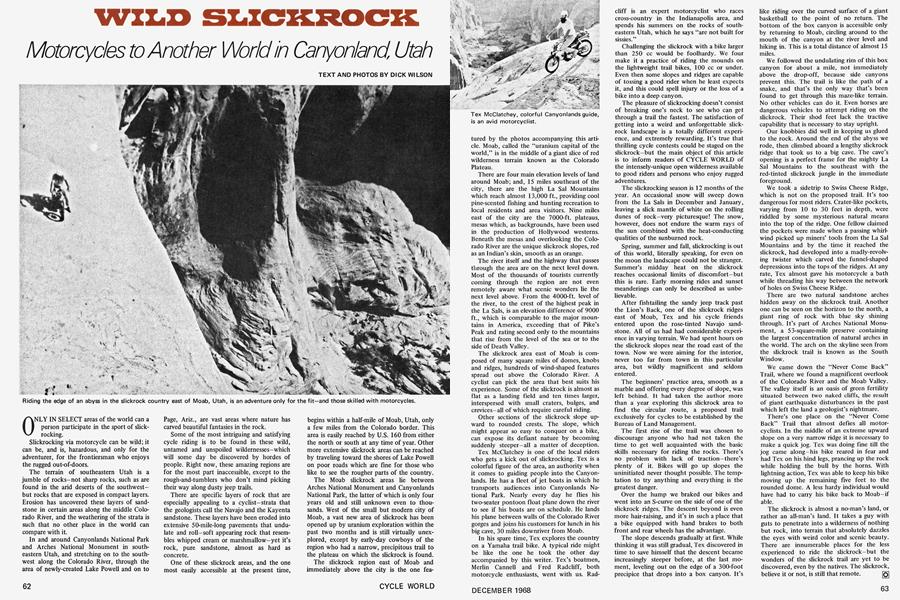

The slickrock region east of Moab and immediately above the city is the one featured by the photos accompanying this article. Moab, called the “uranium capital of the world,” is in the middle of a giant slice of red wilderness terrain known as the Colorado Plateau.

There are four main elevation levels of land around Moab; and, 15 miles southeast of the city, there are the high La Sal Mountains which reach almost 13,000 ft., providing cool pine-scented fishing and hunting recreation to local residents and area visitors. Nine miles east of the city are the 7000-ft. plateaus, mesas which, as backgrounds, have been used in the production of Hollywood westerns. Beneath the mesas and overlooking the Colorado River are the unique slickrock slopes, red as an Indian’s skin, smooth as an orange.

The river itself and the highway that passes through the area are on the next level down. Most of the thousands of tourists currently coming through the region are not even remotely aware what scenic wonders lie the next level above. From the 4000-ft. level of the river, to the crest of the highest peak in the La Sals, is an elevation difference of 9000 ft., which is comparable to the major mountains in America, exceeding that of Pike’s Peak and rating second only to the mountains that rise from the level of the sea or to the side of Death Valley.

The slickrock area east of Moab is composed of many square miles of domes, knobs and ridges, hundreds of wind-shaped features spread out above the Colorado River. A cyclist can pick the area that best suits his experience. Some of the slickrock is almost as flat as a landing field and ten times larger, interspersed with small craters, bulges, and crevices-all of which require careful riding.

Other sections of the slickrock slope upward to rounded crests. The slope, which might appear so easy to conquer on a bike, can expose its defiant nature by becoming suddenly steeper—all a matter of deception.

Tex McClatchey is one of the local riders who gets a kick out of slickrocking. Tex is a colorful figure of the area, an authority when it comes to guiding people into the Canyonlands. He has a fleet of jet boats in which he transports audiences into Canyonlands National Park. Nearly every day he flies his two-seater pontoon float plane down the river to see if his boats are on schedule. He lands his plane between walls of the Colorado River gorges and joins his customers for lunch in his big cave, 30 miles downriver from Moab.

In his spare time, Tex explores the country on a Yamaha trail bike. A typical ride might be like the one he took the other day accompanied by this writer. Tex’s boatmen, Merlin Cannell and Fred Radcliff, both motorcycle enthusiasts, went with us. Radcliff is an expert motorcyclist who races cross-country in the Indianapolis area, and spends his summers on the rocks of southeastern Utah, which he says “are not built for sissies.”

Challenging the slickrock with a bike larger than 250 cc would be foolhardy. We four make it a practice of riding the mounds on the lightweight trail bikes, 100 cc or under. Even then some slopes and ridges are capable of tossing a good rider when he least expects it, and this could spell injury or the loss of a bike into a deep canyon.

The pleasure of slickrocking doesn’t consist of breaking one’s neck to see who can get through a trail the fastest. The satisfaction of getting into a weird and unforgettable slickrock landscape is a totally different experience, and extremely rewarding. It’s true that thrilling cycle contests could be staged on the slickrock-but the main object of this article is to inform readers of CYCLE WORLD of the intensely-unique open wilderness available to good riders and persons who enjoy rugged adventures.

The slickrocking season is 12 months of the year. An occasional snow will sweep down from the La Sals in December and January, leaving a slick mantle of white on the rolling dunes of rock-very picturesque! The snow, however, does not endure the warm rays of the sun combined with the heat-conducting qualities of the sunburned rock.

Spring, summer and fall, slickrocking is out of this world, literally speaking, for even on the moon the landscape could not be stranger. Summer’s midday heat on the slickrock reaches occasional limits of discomfort-but this is rare. Early morning rides and sunset meanderings can only be described as unbelievable.

After fishtailing the sandy jeep track past the Lion’s Back, one of the slickrock ridges east of Moab, Tex and his cycle friends entered upon the rose-tinted Navajo sandstone. All of us had had considerable experience in varying terrain. We had spent hours on the slickrock slopes near the road east of the town. Now we were aiming for the interior, never too far from town in this particular area, but wildly magnificent and seldom entered.

The beginners’ practice area, smooth as a marble and offering every degree of slope, was left behind. It had taken the author more than a year exploring this slickrock area to find the circular route, a proposed trail exclusively for cycles to be established by the Bureau of Land Management.

The first rise of the trail was chosen to discourage anyone who had not taken the time to get well acquainted with the basic skills necessary for riding the rocks. There’s no problem with lack of traction—there’s plenty of it. Bikes will go up slopes the uninitiated never thought possible. The temptation to try anything and everything is the greatest danger.

Over the hump we braked our bikes and went into an S-curve on the side of one of the slickrock ridges. The descent beyond is even more hair-raising, and it’s in such a place that a bike equipped with hand brakes to both front and rear wheels has the advantage.

The slope descends gradually at first. While thinking it was still gradual, Tex discovered in time to save himself that the descent became increasingly steeper before, at the last moment, leveling out on the edge of a 300-foot precipice that drops into a box canyon. It’s like riding over the curved surface of a giant basketball to the point of no return. The bottom of the box canyon is accessible only by returning to Moab, circling around to the mouth of the canyon at the river level and hiking in. This is a total distance of almost 15 miles.

We followed the undulating rim of this box canyon for about a mile, not immediately above the drop-off, because side canyons prevent this. The trail is like the path of a snake, and that’s the only way that’s been found to get through this maze-like terrain. No other vehicles can do it. Even horses are dangerous vehicles to attempt riding on the slickrock. Their shod feet lack the tractive capability that is necessary to stay upright.

Our knobbies did well in keeping us glued to the rock. Around the end of the abyss we rode, then climbed aboard a lengthy slickrock ridge that took us to a big cave. The cave’s opening is a perfect frame for the mighty La Sal Mountains to the southeast with the red-tinted slickrock jungle in the immediate foreground.

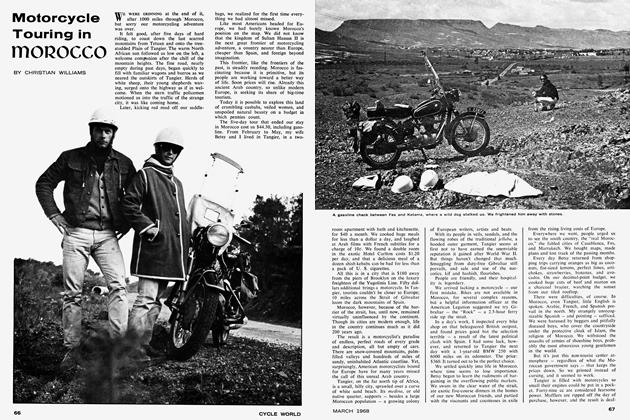

We took a sidetrip to Swiss Cheese Ridge, which is not on the proposed trail. It’s too dangerous for most riders. Crater-like pockets, varying from 10 to 30 feet in depth, were riddled by some mysterious natural means into the top of the ridge. One fellow claimed the pockets were made when a passing whirlwind picked up miners’ tools from the La Sal Mountains and by the time it reached the slickrock, had developed into a madly-revolving twister which carved the funnel-shaped depressions into the tops of the ridges. At any rate, Tex almost gave his motorcycle a bath while threading his way between the network of holes on Swiss Cheese Ridge.

There are two natural sandstone arches hidden away on the slickrock trail. Another one can be seen on the horizon to the north, a giant ring of rock with blue sky shining through. It’s part of Arches National Monument, a 53-square-mile preserve containing the largest concentration of natural arches in the world. The arch on the skyline seen from the slickrock trail is known as the South Window.

We came down the “Never Come Back” Trail, where we found a magnificent overlook of the Colorado River and the Moab Valley. The valley itself is an oasis of green fertility situated between two naked cliffs, the result of giant earthquake disturbances in the past which left the land a geologist’s nightmare.

There’s one place on the “Never Come Back” Trail that almost defies all motorcyclists. In the middle of an extreme upward slope on a very narrow ridge it is necessary to make a quick jog. Tex was doing fine till the jog came along-his bike reared in fear and had Tex on his hind legs, prancing up the rock while holding the bull by the horns. With lightning action, Tex was able to keep his bike moving up the remaining five feet to the rounded dome. A less hardy individual would have had to carry his bike back to Moab—if able.

The slickrock is almost a no-man’s land, or rather an all-man’s land. It takes a guy with guts to penetrate into a wilderness of nothing but rock, into terrain that absolutely dazzles the eyes with weird color and scenic beauty. There are innumerable places for the less experienced to ride the slickrock-but the wonders of the slickrock trail are yet to be discovered, even by the natives. The slickrock, believe it or not, is still that remote. [Q]