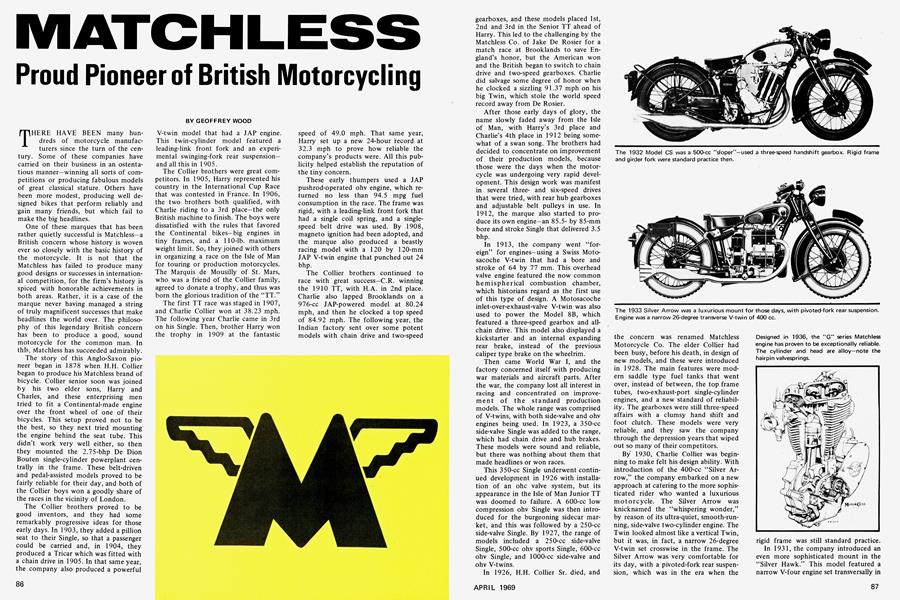

MATCHLESS

Proud Pioneer of British Motorcycling

GEOFFREY WOOD

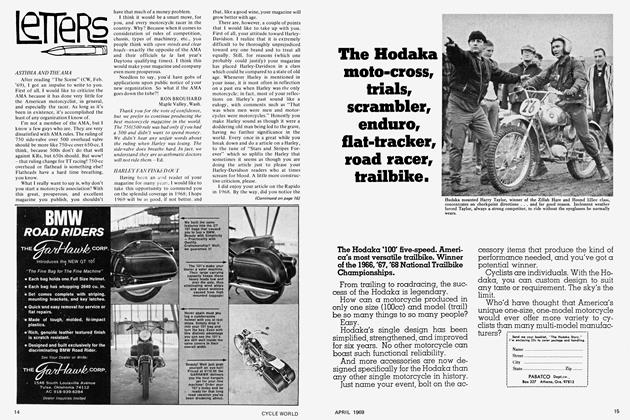

THERE HAVE BEEN many hundreds of motorcycle manufacturers since the turn of the century. Some of these companies have carried on their business in an ostentatious manner—winning all sorts of competitions or producing fabulous models of great classical stature. Others have been more modest, producing well designed bikes that perform reliably and gain many friends, but which fail to make the big headlines.

One of these marques that has been rather quietly successful is Matchless—a British concern whose history is woven ever so closely with the basic history of the motorcycle. It is not that the Matchless has failed to produce many good designs or successes in international competition, for the firm’s history is spiced with honorable achievements in both areas. Rather, it is a case of the marque never having managed a string of truly magnificent successes that make headlines the world over. The philosophy of this legendary British concern has been to produce a good, sound motorcycle for the common man. In this, Matchless has succeeded admirably.

The story of this Anglo-Saxon pioneer began in 1878 when H.H. Collier began to produce his Matchless brand of bicycle. Collier senior soon was joined by his two elder sons, Harry and Charles, and these enterprising men tried to fit a Continental-made engine over the front wheel of one of their bicycles. This setup proved not to be the best, so they next tried mounting the engine behind the seat tube. This didn’t work very well either, so then they mounted the 2.75-bhp De Dion Bouten single-cylinder powerplant centrally in the frame. These belt-driven and pedal-assisted models proved to be fairly reliable for their day, and both of the Collier boys won a goodly share of the races in the vicinity of London.

The Collier brothers proved to be good inventors, and they had some remarkably progressive ideas for those early days. In 1903, they added a pillion seat to their Single, so that a passenger could be carried and, in 1904, they produced a Tricar which was fitted with a chain drive in 1905. In that same year, the company also produced a powerful V-twin model that had a JAP engine. This twin-cylinder model featured a leading-link front fork and an experimental swinging-fork rear suspension— and all this in 1905.

The Collier brothers were great competitors. In 1905, Harry represented his country in the International Cup Race that was contested in France. In 1906, the two brothers both qualified, with Charlie riding to a 3rd place-the only British machine to finish. The boys were dissatisfied with the rules that favored the Continental bikes—big engines in tiny frames, and a 110-lb. maximum weight limit. So, they joined with others in organizing a race on the Isle of Man for touring or production motorcycles. The Marquis de Mousilly of St. Mars, who was a friend of the Collier family, agreed to donate a trophy, and thus was born the glorious tradition of the “TT.”

The first TT race was staged in 1907, and Charlie Collier won at 38.23 mph. The following year Charlie came in 3rd on his Single. Then, brother Harry won the trophy in 1909 at the fantastic speed of 49.0 mph. That same year, Harry set up a new 24-hour record at 32.3 mph to prove how reliable the company’s products were. All this publicity helped establish the reputation of the tiny concern.

These early thumpers used a JAP pushrod-operated ohv engine, which returned no less than 94.5 mpg fuel consumption in the race. The frame was rigid, with a leading-link front fork that had a single coil spring, and a singlespeed belt drive was used. By 1908, magneto ignition had been adopted, and the marque also produced a beastly racing model with a 120 by 120-mm JAP V-twin engine that punched out 24 bhp.

The Collier brothers continued to race with great success—C.R. winning the 1910 TT, with H.A. in 2nd place. Charlie also lapped Brooklands on a 976-cc JAP-powered model at 80.24 mph, and then he clocked a top speed of 84.92 mph. The following year, the Indian factory sent over some potent models with chain drive and two-speed gearboxes, and these models placed 1st, 2nd and 3rd in the Senior TT ahead of Harry. This led to the challenging by the Matchless Co. of Jake De Rosier for a match race at Brooklands to save England’s honor, but the American won and the British began to switch to chain drive and two-speed gearboxes. Charlie did salvage some degree of honor when he clocked a sizzling 91.37 mph on his big Twin, which stole the world speed record away from De Rosier.

After those early days of glory, the name slowly faded away from the Isle of Man, with Harry’s 3rd place and Charlie’s 4th place in 1912 being somewhat of a swan song. The brothers had decided to concentrate on improvement of their production models, because those were the days when the motorcycle was undergoing very rapid development. This design work was manifest in several threeand six-speed drives that were tried, with rear hub gearboxes and adjustable belt pulleys in use. In 1912, the marque also started to produce its own engine—an 85.5by 85-mm bore and stroke Single that delivered 3.5 bhp.

In 1913, the company went “foreign” for engines—using a Swiss Motosacoche V-twin that had a bore and stroke of 64 by 77 mm. This overhead valve engine featured the now common hemispherical combustion chamber, which historians regard as the first use of this type of design. A Motosacoche inlet-over-exhaust-valve V-twin was also used to power the Model 8B, which featured a three-speed gearbox and allchain drive. This model also displayed a kickstarter and an internal expanding rear brake, instead of the previous caliper type brake on the wheelrim.

Then came World War I, and the factory concerned itself with producing war materials and aircraft parts. After the war, the company lost all interest in racing and concentrated on improvement of the standard production models. The whole range was comprised of V-twins, with both side-valve and ohv engines being used. In 1923, a 350-cc side-valve Single was added to the range, which had chain drive and hub brakes. These models were sound and reliable, but there was nothing about them that made headlines or won races.

This 350-cc Single underwent continued development in 1926 with installation of an ohc valve system, but its appearance in the Isle of Man Junior TT was doomed to failure. A 600-cc low compression ohv Single was then introduced for the burgeoning sidecar market, and this was followed by a 250-cc side-valve Single. By 1927, the range of models included a 250-cc side-valve Single, 500-cc ohv sports Single, 600-cc ohv Single, and 1000-cc side-valve and ohv V-twins.

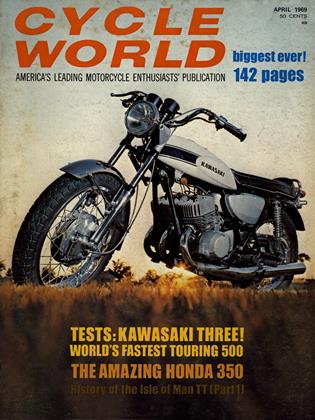

In 1926, H.H. Collier Sr. died, and the concern was renamed Matchless Motorcycle Co. The elder Collier had been busy, before his death, in design of new models, and these were introduced in 1928. The main features were modern saddle type fuel tanks that went over, instead of between, the top frame tubes, two-exhaust-port single-cylinder engines, and a new standard of reliability. The gearboxes were still three-speed affairs with a clumsy hand shift and foot clutch. These models were very reliable, and they saw the company through the depression years that wiped out so many of their competitors.

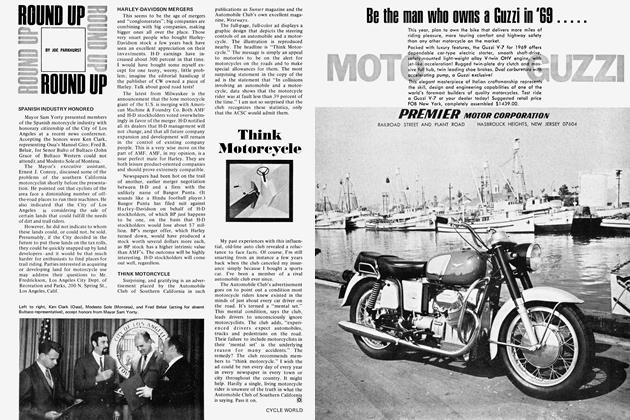

By 1930, Charlie Collier was beginning to make felt his design ability. With introduction of the 400-cc “Silver Arrow,” the company embarked on a new approach at catering to the more sophisticated rider who wanted a luxurious motorcycle. The Silver Arrow was knicknamed the “whispering wonder,” by reason of its ultra-quiet, smooth-running, side-valve two-cylinder engine. The Twin looked almost like a vertical Twin, but it was, in fact, a narrow 26-degree V-twin set crosswise in the frame. The Silver Arrow was very comfortable for its day, with a pivoted-fork rear suspension, which was in the era when the rigid frame was still standard practice.

In 1931, the company introduced an even more sophisticated mount in the “Silver Hawk.” This model featured a narrow V-four engine set transversally in the frame. The 593-cc powerplant featured ohc valve operation. The deluxe specifications included such things as a chromed fuel tank and an instrument panel. A fully s prung sidecar was available. This V-four sold at a price that was actually not terribly far above the ohv 500-cc Single’s price, but the scarcity of pounds in those depression years prevented the sales figure from ever attaining a commercially profitable rate. The Four was dropped from production within a few years-the verdict being excellent engineering, but unsound business practice. Today, the Silver Hawk is prized as a collector’s item, and as a great classic, but few are known to exist. During these years, the international road racing scene had taken on great stature, with many companies fielding works teams on everything from fine handling ohc Singles to exotic watercooled and supercharged Fours. The Matchless name (under the company name of Associated Motor Cycles, after 1938) was quietly absent from this grand prix game, preferring instead to develop a range of bikes for the man on the street. In all fairness to the marque, it should be stated that the firm conducted an intensive racing program under the AJS banner, which was a policy that was continued after World War II.

In 1931, the Matchless Co. bought the A.J. Stevens concern, and thereafter the AJS and Matchless began to acquire similar specifications. During the early 1930s, the fashion in England was for “sloping” Singles, and Matchless responded with 500-cc side-valve and ohv models that were quite light. With a rigid frame, girder front fork, and three-speed gearbox, the side-valve machine weighed only 220 lb.

The big side-valve V-twin had been redesigned in 1929, and this model, called the Model X, was produced until World War II. The market for the husky 1000-cc V-twins was substantial during the prewar days in England, since the sidecar owners loved the low-speed power, reliability, and low maintenance expense that these chuggers possesed.

In 1936, the amalgamation of the AJS and Matchless was apparent when the “G” series was introduced. These 3 50-cc and 500-cc Singles featured pushrod-operated ohv powerplant, a four-speed footshift gearbox, a rigid frame, and a girder front fork. About the only difference between the AJS and Matchless in later years was the location of the magneto—which was in front of the cylinder on the AJS and behind the cylinder on the big “M.” These thumpers were known as exceptionally rugged bikes, and their handling and performance were up to the high standards that motorcyclists had come to expect during the late 1930s.

These G models were soon followed by the Clubman and Clubman Special models, which were more highly tuned Singles for the sporting minded riders. The Clubman Special model could be purchased in competition trim with a 21-in. front wheel, knobby tires, upswept exhaust, and special gear ratios. These Singles were used in trials and scrambles events with great success during the late 1930s, and this publicity helped further the marque’s export sales.

During the war, the factory once again was switched over to wartime production, only this time it was for military motorcycles. The model produced was the G3L—the ohv 350 thumper that was exceptionally reliable. Altogether, no less than 80,000 bikes were produced during the war, and even today one can occasionally see the trusty little Singles thumping down the country lanes of England.

After the war, the marque narrowed its range down to the G-3 (350-cc) model and G-80 (500-cc) model—both with “iron” engines and the new hydraulically dampened telescopic front fork. The design was cleaned up a little from the prewar days, but it remained the basic design that was laid down in 1936.

The company also produced some trials mounts, which were mainly 350s set up with 21-in. front wheels, knobby tires, upswept exhaust, wide ratio gears, and alloy fenders. These were superb little trials mounts, and men such as Hugh Viney and the Ratcliffe brothers established a splendid reputation with these machines. The 500-cc model was used extensively in motocross racing, and Basil Hall scored many wins on his factory model.

It was during these immediate postwar years that the company greatly expanded its export market, with the United States figuring prominently in this expansion. The fine Singles were especially loved by California desert riders, because handling, traction, and reliability were better than any of the others for cross-country and scrambles races of that era. Indeed, AJS and Matchless riders were the most successful of all the riders until the late 1950s, and it would take a story in itself just to cover all of the victories racked up by riders such as Dutch Sterner, Del Kuhn, Julius Kroeger, Guy Louis, Aub LeBard, Earl Flanders, Don Bishop, Rod Coates, Ralph Adams, Lee Carey, Dalton Holliday, Vern Hancock, Bud Ekins, Butsy Mueller, Dick Dean, and Fred Borgeson.

In 1949, the marque made another great step forward when the new “Super Clubman” model was introduced. The new Matchless was a 500-cc Twin with a bore and stroke of 66 and 72.8 mm. It featured a three-bearing crankshaft, alloy head, and a comfortable dual seat.

The Twin displayed an additional characteristic—the new swinging arm rear suspension. This new frame was a major contributor to rider comfort and roadability, and it was available on all of the models.

During the next several years, the range of models expanded to include mounts for trials and motocross riders, and these fine Singles established a great record on both sides of the Atlantic. The 1952 catalog listed a total of nine models-one Twin and eight Singles. This also was the year that the AJS and Matchless Singles became virtually the same bike, with the magneto being mounted in front of the cylinder on both makes.

(Continued on page 110)

Continued from page 89

Serious touring riders loved the G-9 500-cc Twin for its comfort, 90-95 mph performance, and sporting appearance. The Twin had a four-speed gearbox with ratios of 13.35:1, 8.8:1, 6.4:1, and 5.0:1. A favorite with everyday riders was the 350-cc Single—a reliable model with brisk performance. The G-3L model was built around a rigid frame; the G-3LS had a spring frame. Next came the G-80 and G-80S models—both 500-cc Singles in rigid and spring frame trim. An improvement to the Singles that year was the alloy head, which helped the engines run cooler and allowed higher compression ratios to be used. These 85-90-mph thumpers were known for their reliability and low maintenance expense, and they proved popular with riders the world over.

The 1952 catalog listed four competition models—two rigid frame models (350 and 500 cc) for trials and two spring frame models (350 and 500 cc) for motocross. The engines were considerably modified on these competition mounts, with alloy cylinders and heads, special cams, high compression pistons on the two motocross models, and a heavier gearbox with wide ratio gears on the trials bikes and close ratio gears on the scrambler models. Both the trials and scrambles versions were delivered with 3.00 by 21-in. front tires and 4.00 by 19-in. rear tires. Both models were fitted with small 2.25-gal. fuel tanks. The wheelbase was a short 52.5 in. on the competition models, and alloy fenders, sports solo seats, and upswept exhaust systems were fitted.

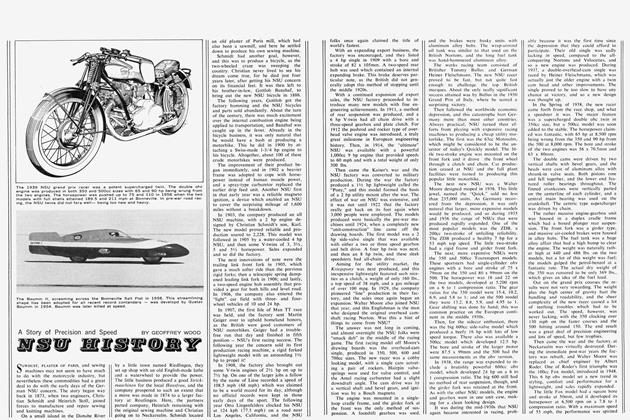

The next significant chapter in the history of the marque began in 1951 when a racing department was established to develop the 500-cc Twin. The idea was to determine if the standard G-9 Twin showed potential as a road racing model, with the long range goal being to produce a pukka racing machine at a cost well below that of an ohc Single. The Twin first appeared in the 1951 Manx Grand Prix in the hands of Robin Sherry, who proceeded to garner a 4th place with the machine behind the famous Norton Manx Singles. Justifiably encouraged, the factory continued to develop the Twin in preparation for the 1952 Manx GP. Derek Farrant rode the Matchless prototype that year, and he led from start to finish-setting up race and lap records at 88.65 and 89.64 mph.

This sensation virtually required the factory to start production of the Twin, which appeared in 1953 as the G-45 model. The G-45 was produced for five years, during which time it underwent detailed improvements. By 1956, the 66 by 72.8-mm Twin was producing 48 bhp at 7200 rpm on a 10.0:1 compression ratio, which provided a level road speed of 120 mph without a fairing. The G-45 had a four-speed gearbox with ratios of 8.57:1, 6.19:1, 5.0:1, and 4.58:1 ; and the wheelbase was 55.25 in.

A deep, knee-knotched 6-gal. fuel tank was used, and the dry weight was 320 lb. Tire sizes were 3.00 by 19-in. front and 3.25 by 19-in. rear, and both brakes were a huge 8.25-in. size with an air scoop and twin leading shoe arrangement being used on the front brake. This Twin was a beautiful thing with its massive alloy cylinder and head, plus the pair of 1.094-in. GP carbs, and it attained a splendid record in the hands of private owners the world over.

This range of models remained much the same until 1956, when a new 600-cc Twin was introduced that had a bore and stroke of 72 and 72.8 mm, respectively. Gone were the rigid frame models, with the catalog down to only seven machines—the 500and 600-cc Twins, the 350and 500-cc road Singles, the G-80CS scrambler, the G-45 road racer, and the new G-3LC trials model.

This new trials model was a direct result of the works mounts that had done so well in 1954 and 1955 (Artie Ratcliffe won the 1954 Scottish Six Days Trial), and it had the swinging arm frame for the first time. A trim and fine handling Single, the G-3LC ran on a 6.5:1 compression ratio and pumped out 18 bhp at 5750 rpm. The bike weighed a light 320 lb. and had gear ratios of 21.0:1, 16.0:1, 10.3:1, and 6.6:1. Very few of these superb trials models ever made their way to this country, but they achieved a great number of outstanding successes in British and Scottish trials.

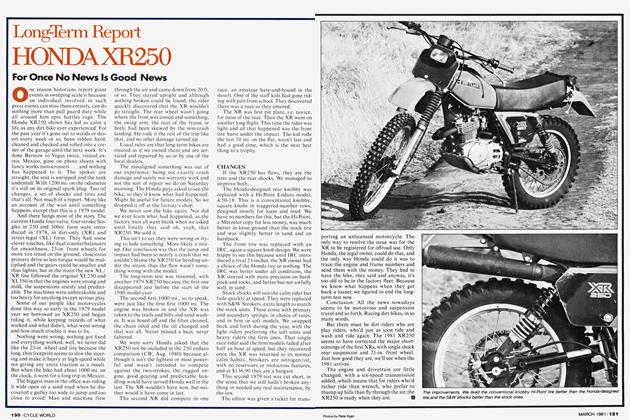

The range of machines continued much the same until 1959, when the G-45 Twin was dropped and the G-50 ohc Single was introduced. The G-50 also was derived from a previous model—this one the 350-cc 7R AJS racer. The big Single had a bore and stroke of 88.5 by 76.7 mm, and it pumped out 47 bhp at 7200 rpm on a 10.6:1 compression ratio. The Single breathed through a huge 1.375-in. GP carburetor, and it was known for being able to power a very high gear ratio. The Matchless was slightly slower than the double-knocker Manx Norton, but its simple chain-driven single-cam engine was easier to tune and less expensive to maintain than the Manx. With a top speed of 125 mph, plus good handling, the G-50 proved to be especially popular with the private owners.

Other notable changes in 1959 included the increasing of the 600-cc Twin’s stroke to 79.3 mm, thus making it a full blown 650. The trials 350 also was improved by chopping the weight to 306 lb. and increasing the ground clearance to a whopping 10 in. The trials mount continued to be the finest bike of its type in the world.

During the early 1960s, the international motorcycle scene underwent a great change with the arrival of the Japanese models on the market. This had a profound effect on the British scene, and especially upon the Matchless. In 1956, AMC purchased Norton Motors, Ltd., and within a few years the standardization began within the AJSMatchless-Norton range of machines. The first to go were the Norton Singles in favor of the AMC design, and then the AMC Twin went by the board in favor of the big 650and 750-cc Norton powerplants. The lusty G-50 racer also was dropped at the end of the 1963 season—a fact that saddened motorcycle sportsmen throughout the world.

During these years, the design progress seemed to stagnate at the factory, with the only new model being the G-85CS scrambler. This 500-cc Single was produced in 1966 and 1967 as a fire breathing motocross mount with a 1.375-in. GP carburetor, Métissé type frame with the central frame tube serving as an oil tank, light 300-lb. weight, and 42-bhp engine. The red hot twostrokes already had taken the play away, though, and this expensive scrambler faded from the picture.

During 1967, the company was known to be virtually bankrupt, and it appeared that the famous name would disappear. At the last hour, a new company was formed when Manganese Bronze Holdings bought out the Norton-Matchless Co., plus the old Villiers concern, and today the future looks brighter for the big M. At present, the range is comprised of the Norton Atlaspowered street and scrambles Twins, plus the G-80CS scrambles model. The bore and stroke of the trusty old thumper was changed to 86 by 86 mm a few years ago in order to obtain greater rpm and power, but the design is still much the same as it was in 1952, or even 1936, for that matter! These fine Singles are probably the most reliable scrambles type mounts going, though, and this, plus the good handling, ensures a devoted following of American riders, [o]