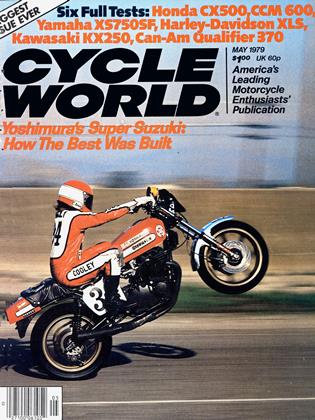

THE NEW WHIZZER

“Ride One and You’ll Buy One”

Henry N. Manney III

As you have probably noticed, dear reader, from time to time we like to present a Salon of some bit of significant machinery which has. for better or worse, made its mark on motorcycling history. Such a case was the celebrated Whizzer, of course not a proper motorcycle at all technically speaking but a motorizing kit for bicycles. It is not to laugh, however, at this arrangement (historically speaking) as did not many racing voiturettes of the early 1900s go under different proprietary names when powered by the universal De Dion-Bou ton engine? At any

rate the Whizzer sprung from the brow of Dietrich Kohlsaat, pres of the Whizzer Motor Corp of Detroit. Mich, sometime in the late ’30s or early '40s and sounds very much like a child of the depression, boasting as it did that one could ride five miles for a penny. Nowadays you can't get a poke> in the eye with a burnt stick for a penny. Now the idea of '‘clip-on” motors for bicycles is nothing new. indeed the Russian engineer P.I. Boya produced an ermine-powered one for the Czarevitch in the late '80s, and the flavour of Pres Kohlsaat’s name prompts one to turn to the library for a book on Derivations & Variations except that there doesn't seem to be one. Most early motorcycles were, in effect, nothing but Velos with ciip-ons and it seems that through the years, in Europe more than in the USA. elip-ons (or mopeds. as they came to be known) have been with us.

The Whizzer. however, is w orthy of special attention as not only is it Americanmade but also four-stroke, a rare bird indeed. The moot point of whether the reliable Whizzer engine was simply an adaptation of some industrial power plant or a fresh re-do of already familiar specifications is lost in the mists of antiquity but the fascination of the Whizzer lies in how the hoary belt-drive concept, old as the industry, could be revived to be given a new life. Part of the appeal was the “package." in today's marketing terms, which included the complete engine itself, fuel tank, jockey-pulley clutch, rear sheave, belts for same plus all necessary hardware to attach the 27 lb. lump to a suitable bicycle, in the case of our Salon subject a gent's model heavy-duty Schwinn. (What ladies did is not mentioned although there is a nice drawing of some young thing in shorts and saddle shoes riding one-up in the Rockies, no less.) In 1942 the package cost S59.95 for which one received a nice big box from Pontiac freight prepaid, these being the days when you could still count on having freight delivered, let alone arriving at all. In addition, easy terms or C.O.D. w ere available and if the order were sent in within seven days (prettv tricks as our brochure is undated) a heavy-duty stand was yours for an additional $2. Imagine. The mouths of paper-boys all over America were undoubtedly salivating as real motorcycles, even superannuated Harley JDs. were far too heavy and complicated (not to mention illegal) for impecunious kids.

What you got for your $59.95 was a fairly straightforward fiathead Single of oversquare dimensions (2‘A x 2N in.) giving 8.5 eu. in. displacement ( 133cc) w hich produced on a good day 1% bhp. The three-ring piston rode on a bushed little end and at the beginning rejoiced in roller rod and mains, the rod bearing later being simplified toa plain insert which probably also indicates some drastic modification to the oiling system, perhaps to accommodate an eventual rise in horsepower to approximately 3 bhp at 3700 rpm. The valves. looking rather like glorified roofing nails in the fashion of the day. w ere of 0.75 in. diameter and although the compression ratio started at 6.5:1 it eventually dropped to 6.32:1 by 1947 which perhaps says something about the quality of even the cheapest regular at that time.

Ignition was looked after by the familiar flywheel mag. points condenser et al even as on Bultacos although a magneto air gap clearance is listed along with the other normal ones. From the brochure it seems as if a side-draft carb. very modern and car-type with float bowl etc was used although the very complete manual warns prospective purchasers not to fiddle with the carburetor screws or other engine settings (such as points, magneto, or fullyenclosed tappets) as they were set at the factory. If anything horrid comes up. take the machine to your Whizzer dealer and we thought that was new? Later, it seems, a straight-in carb was fitted even if the bore probably stayed at a healthy Vis in. Lighting in those days was usually looked after by a visit to the bicycle shop where all sorts of battery-powered devices could be found or, in desperate cases, one of those nasty little generators that ran off the tyre. Much later Whizzer marketed its own built-in generator which didn't fall off in full flight, anyway.

The owner's manual for the Whizzer is a model of its kind and our lives would all be a lot easier if motorcvcle ow ner's manuals, let alone the so-called workshop manuals, were as complete. Nice large draw ings not only showed but numbered all the little bits the purchaser was supposed to get with his Box and additionally showed step by step just how to install the apparatus on the bicycle. Fundamentally, the engine sat in three clamps in the middle of the loop frame, just above the pedals in what was known in the 1910s as the Werner Position (nothing to do with the Kama Sutra). These clamps were rubber-insulated from the frame and according to the brochures practically eliminated all vibration. From there, or properly speaking from the crankshaft pulley, a short Vee-belt ascended to the jockey-pulley-clutch lashup and thence down again, via a longer belt, to a sheave or final drive rim nipped into the spokes of the rear wheel. Rear wheel, as is normal, and engine were both subject to “budging” in their mountings to give the proper belt tension; these days with nice Gates belts (made for various industrial uses) their life is three to five thousand miles but 1 have heard many horror tales of incurable slip . . . the parts list mentions longer and shorter belts)... or else a loud and paralyzing thwack on the bum at some critical moment. The manual, besides giving full instructions on what and w hat not to do installing the engine, featured an illustrated parts list that made the life of the Whizzer owner in Owl Foot. Wis. a little easier plus prices for representative parts such as float bowl 79c, complete gasket set $6.40, dutch pulley bearing bushing 8c, exhaust tail pipe 65C. piston $2.25 (to 0.020 over), crankcase Welch plug (!) 2c, head gasket 31C and so on. Where have we gone wrong? In later years the accessory list expanded as accessory lists tend to do, satisfying the craving for speed or comfort with ohv conversions, trick pipes (as on our Salon bike), saddlebags, foxtails and probably bigger rear sheaves.

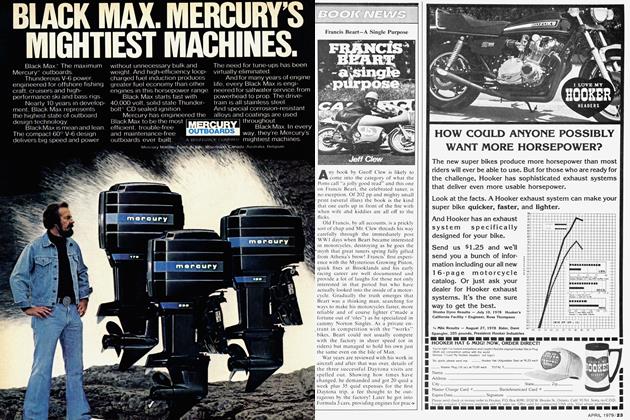

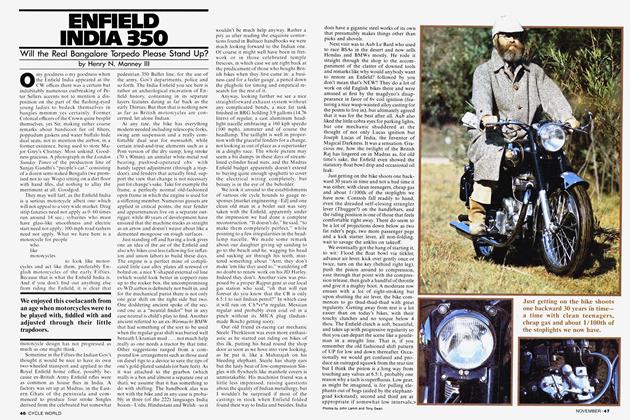

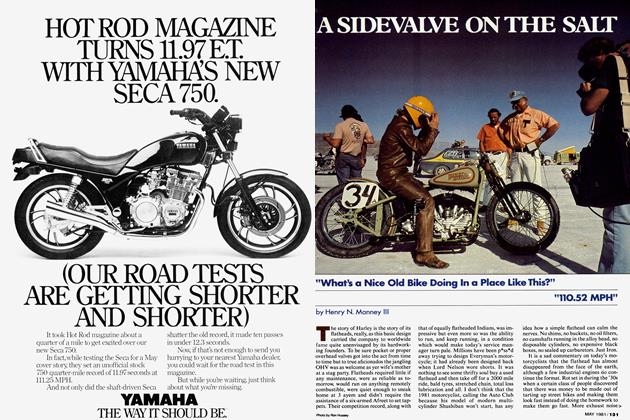

Riding the Whizzer is no great trick, apparently, even such a splendid example as shown belonging to Sterling Pope w ho is one of the Locomotives of the Whizzer O.C. His. as you can see, is in a fine state of fettle and boasts of a late 1952 engine w hich puts out 3 bhp at 4500 rpm. The drill is to put the bike on the stand, turn on the gas from the 5 qt. tank (there is 8 oz. of 30 wt. in the sump), apply the carburetor choke, depress the handlebar mounted compression release and then pedal like sixty, dropping the compression release at some appropriate time. Alternatively the bike may just be pedaled away or rolled down a hill but the method above is easier on the belts. In any case, the end result should be a subdued popping from the exhaust followed by a more definite sound which indicates that all 133ec are in fact running. The next step is to depress the clutch lever on the left handlebar, roll the Whizzer off its stand, and in time honoured fashion regulate both throttle (normal m/c on right) and clutch to get under way. perhaps with a little Light Pedal Assistance. Because of the 9:1 engine to rear wheel ratio, acceleration is not particularly brisk at first (Mr. Pope races mopeds) but as the rpm gather themselves the device goes along well on its 26 x 2.125s and can even work up to 40-45 mph although according to the owmer. it “runs best” around 20. Mr. Editor Girdler essayed a tour of the block and returned satisfied with the machine’s performance. Equally to his liking was the straight-pipeeum-megaphone, suitable for boys of all ages. Mr. Pope reports that when chopper riders ride up for a closer look he revs the Whizzer engine, to their apparent delight.

The Schwinn frame seems solid enough, even with rigid bicycle suspension, to hold the road properly and not play tricks with twisting of the frame or even the dreaded

sideslip on corners, even though nobody would mistake it for a Manx Norton. Brakes are another matter, as New Departure coaster hubs are fitted front and rear which look (and feel) as if you had no brakes at all although in 1942 nobody had very much. A more rapid deceleration can be managed by smartly mashing on that decompression lever. What with the way things are going with the Ayrabs and oil. we had better start looking in those old barns. Whizzers in decrepit form are still fairly common and cheap. 100 mpg is not to be sneezed at vs the bus stop, especially w hen you can always pedal the bike home!