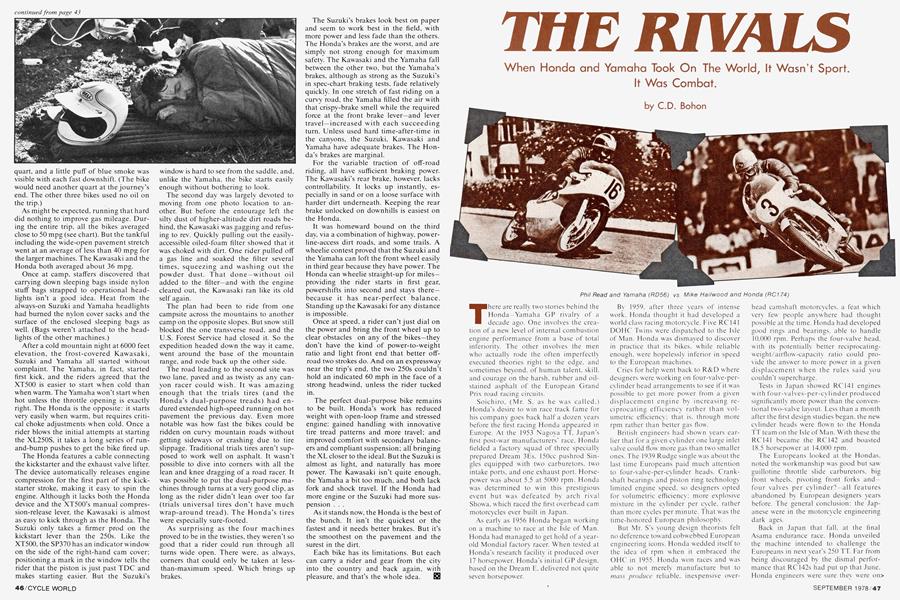

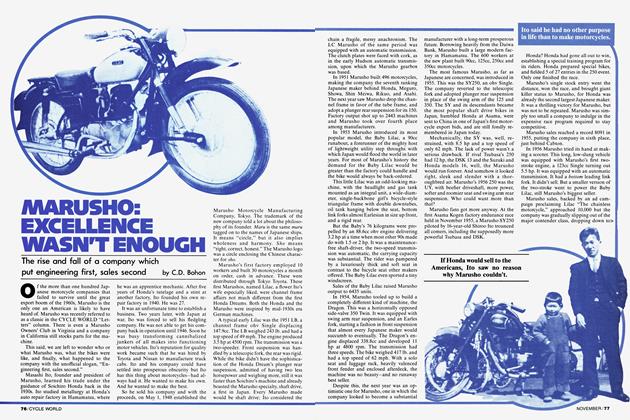

THE RIVALS

When Honda and Yamaha Took On The World, It Wasn’t Sport. It Was Combat.

C.D. Bohon

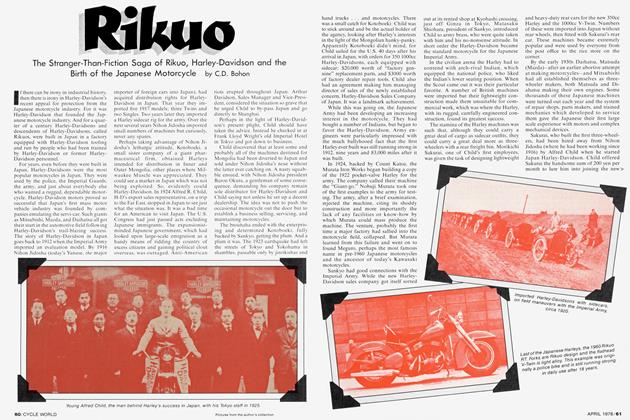

There are really two stories behind the Honda—Yamaha GP rivalry of a decade ago. One involves the creation of a new level of internal combustion engine performance from a base of total inferiority. The other involves the men who actually rode the often imperfectly executed theories right to the edge, and sometimes beyond, of human talent, skill, and courage on the harsh, rubber and oilstained asphalt of the European Grand Prix road racing circuits.

Soichiro, (Mr. S, as he was called.) Honda's desire to w in race track fame for his company goes back half a dozen years before the first racing Honda appeared in Europe. At the 1953 Nagoya TT, Japan's first post-war manufacturers' race, Honda fielded a factory squad of three specially prepared Dream 3Es. 150cc pushrod Singles equipped with two carburetors, two intake ports, and one exhaust port. Horsepower was about 5.5 at 5000 rpm. Honda was determined to win this prestigious event but was defeated by arch rival Showa, w'hich raced the first overhead cam motorcycles ever built in Japan.

As early as 1956 Honda began working on a machine to race at the Isle of Man. Honda had managed to get hold of a yearold Mondial factory racer. When tested at Honda’s research facility it produced over 17 horsepower. Honda's initial GP design, based on the Dream E. delivered not quite seven horsepower. Bv 1959, after three years of intense w'ork. Honda thought it had developed a world class racing motorcycle. Five RC141 DOHC Twins were dispatched to the Isle of Man. Honda was dismayed to discover in practice that its bikes, while reliable enough, were hopelessly inferior in speed to the European machines.

Cries for help went back to R&D where designers were working on four-valve-percylinder head arrangements to see if it was possible to get more power from a given displacement engine by increasing reciprocating efficiency rather than volumetric efficiency; that is. through more rpm rather than better gas flow'.

British engineers had shown years earlier that for a given cylinder one large inlet valve could flow more gas than two smaller ones. The 1939 Rudge single was about the last time Europeans paid much attention to four-valve-per-cylinder heads. Crankshaft bearings and piston ring technology limited engine speed, so designers opted for volumetric efficiency; more explosive mixture in the cylinder per cycle, rathef than more cycles per minute. That was the time-honored European philosophy.

But Mr. S’s young design theorists felt no deference toward cobwebbed European engineering icons. Honda wedded itself to the idea of rpm when it embraced the OHC in 1955. Honda won races and was able to not merely manufacture but to mass produce reliable, inexpensive overhead camshaft motorcycles, a feat which very few' people anywhere had thought possible at the time. Honda had developed good rings and bearings, able to handle 10,000 rpm. Perhaps the four-valve head, with its potentially better reciprocatingweight/airfiow-capacity ratio could provide the answer to more power in a given displacement when the rules said you couldn’t supercharge.

Tests in Japan showed RC141 engines with four-valves-per-cylinder produced significantly more power than the conventional two-valve layout. Less than a month after the first design studies began, the new' cylinder heads were flown to the Honda TT team on the Isle of Man. With these the RC141 became the RC142 and boasted 18.5 horsepower at 14.000 rpm.

The Europeans looked at the Hondas, noted the workmanship was good but saw guillotine throttle slide carburetors, big front wheels, pivoting front forks and— four valves per cylinder?—all features abandoned by European designers years before. The general conclusion; the Japanese were in the motorcycle engineering dark ages.

Back in Japan that fall, at the final Asama endurance race. Honda unveiled thy machine intended to challenge the Europeans in next year's 250 TT. Far from being discouraged by the dismal performance that RC142s had put up that June, Honda engineers were sure they were on> the right track. The four-valve head and lots of cylinders were the way to go. Separate cam lobes and tappets for each valve eased wear problems, so proportionately heavier valve springs could be used. The spark plug could be located dead center in the combustion chamber, equalizing flame paths to all parts of the cylinder, permitting high compression without detonation, and improving combustion by the turbulence of two converging inlet streams. Valve stems could be made longer in proportion to the valve head, thanks to the better flow-area, valve-weight ratio, allowing longer valve guides, which permitted prolonged high rev running without valve seating problems and leakage. Equallyimportant. the longer valve stem allowed the inlet pipe to approach the valve throat at a much shallower angle, eliminating the sudden turn in front of the valve which hampers two-valve designs.

When the Honda engineers figured all this out they must have danced a Japanese polka. It would take some development to get everything right, not just with valves, but with carburetion. throat design, cam timing, and the like, but it was clear they had climbed to a new design plateau. And there was nobody else up there with them.

The Europeans raced 125 Singles. Honda dispatched a Twin. For its first 250. Honda prepared a Four. Why a Four? Peak rpm is limited by stroke length. More cylinders for a given displacement mean shorter stroke for each. Inertia loads in reciprocating components are reduced. Rpm capability is raised. With the fourvalve head, the more revs you can get. the better.

Honda’s 250 Asama racer, the RC 160. was a doubled version of the RC142. Bore and stroke were 44 x 41mm. displacement 249.2cc. The two overhead camshafts were driven by a bevel shaft and spur pinions on the right side of the engine. Four flat-slide carburetors fed eight intake valves; the eight exhaust valves exhaled through four open megaphones. Compression ratio was 10.15 to 1. Horsepower was 35 at 14.000 rpm giving the 273-lb. machine a top speed of about 125 mph.

Honda expected to stun the Asama opposition into terrified despair with these machines (which technically, not being based on production equipment, were illegal). In fact. Yamaha chose not to field a factory team in the 250 event. But a fellownamed Taneharu Noguchi, on a privateer Yamaha YDS 250 Twin rated at 20 horsepower at 7500 rpm. fought his way to third place among the mighty Hondas before the Yamaha's crankshaft broke.

After the near embarrassment at Asama. Honda substantially modified the RC160. The rear shocks were improved, the leading link forks were traded for a telescopic unit, front and rear tires were made the same size, and the engine was canted forward 30 degrees, all efforts to improve the machine’s bad handling.

Still, at the 1960 TT the RC161-as the machine was now called—could, piloted byAustralian Bob Brown, finish no higher than fourth. 4.5 mph down on the winning MV.

Europeans considered the Honda far too bulky for the 250 class. Thanks to a six pint oil sump at the base of the crankcase, the engine was set high. The 30 degree forward slant of the engine, together with the steep downdraft angle of the carburetors, cocked the four long carburetor velocity stacks up at an awkward angle, forcing the gas tank into a high arch over them and giving the Hondas their characteristic pregnant whale silhouette.

A hydraulic steering damper raised grave suspicions among observers about handling. Up until then steering dampers had only been used in sidecar racing.

The Hondas were interesting noveltymachines. but posed no threat to the European racing elite. Or so the elite believed.

But throughout the 1960 season Honda riders told of tantalizing bursts of speed that made their bikes almost frighteningly fast. Then for no clear reason revs w'ould drop by 1000 or more and a bike would lose its zing. Still, the machines could run happily at 14.000 rpm —an unheard of speed—and valve float could be held off' until 17.000 rpm (the MVs had a safety margin of only a few hundred rpm). The concepts were right. They just needed some refining. Another Australian. Tom Phillis, showed what the Fours were capable of when he brought his RC 161 home in second place in the Ulster GP. less than three seconds behind the winning MV. his average speed only about a tenth of a mile an hour off' the winner's pace.

Despite this promising showing in only its second year of competition, 1960 was a sad and sobering season for Honda. In Holland two Japanese riders. Tanaka and Taniguchi, were hurt in crashes. Bob Brown, coaching the Japanese riders, cautioned them to curb their enthusiasm. At that time there were no paved road racing circuits in Japan and speeds were low. Even at Asama it was a major event when a lap exceeding 100 kilometers per hour (62 mph) w-as first recorded in 1958. Under such circumstances a mistake in judgement. an equipment failure, was more an embarrassment than a danger.

When the Japanese, some in their teens, were exposed to the European circuits for the first time they tended to race with more courage than skill. Brown tried earnestly to calm them down, teach them what he knew about racing Grand Prix motorcycles.

The Japanese listened, the mishaps in Holland admonished them, but still, racing w'as a sport. . . . Then at the end of July, in practice for the German GP. Bob Brown w'as killed. In the first week of August at the Ulster GP Tanaka was so severely injured that it was years before he could walk again. No, this wasn’t a sport. This was combat.

When Honda returned in 1961 the flatslide carburetors were gone, replaced by standard cylindrical types. The long velocity stacks were eliminated, along with the steep downdraft intake angle. The wet sump on the 250 was replaced by a fourpint tank under the seat. The engine was lowered and the single tube frame changed for a more rigid duplex arrangement. The 125cc RC143 was rated at 23 horsepower at 14.000 rpm, the 250cc RC162 Four at 45 horsepower at the same speed. Both could rev safely to 18,000 rpm.

And Honda was back with foreign riders, men who knew' the European circuits. In addition to Phillis there were Redman, Taveri, Robb, Hailwood, McIntyre. Some of the best Japanese riders stayed on, notably Kunimitsu Takahashi, who finished ahead of Mike Hailwood in championship rider points that year, but for the rest of its Grand Prix campaign Honda would pin its hopes and its reputation on the skill and daring of men from Italy, England. Scotland. Australia, Canada and Rhodesia.

At the Isle of Man in 1961 Honda ran riot, grabbing first, second, third, fourth, and fifth in both the 125cc and 250cc events. Englishman Mike Hailwood was the winner in both the 125 and 250, but Scotsman Bob McIntyre sent spectators reeling with his fantastic performance in the 250. He led from the start. . . not only led, but dominated. His standing start opening lap cut 48.8 seconds off the old record and set him half a minute ahead of the second place MV. The whooping howl of the four megaphones on the Honda left no doubt the old order of Grand Prix motorcycling had very definitely changed.

Hondas romped home to victory after victory in the European GPs that year and garnered two world championships: Tom Phillis was the 125 champ and Mike Hailwood wore the crown in the 250. After that nobody made cracks about Oriental NSUs. During that triumphant march across Europe, something happened to jar Honda’s confidence, although it’s likely the Europeans didn’t notice:

Yamaha fielded a GP team.

The Yamahas appeared at the French GP in May and Taneharu Noguchi, who had put the fear of the two-stroke into Honda at Asama in 1959. cantered home eighth in the 125cc event. Teammate Fumio Ito. who beat a picked Honda factory team in 1955 on a Marusho. placed eighth in the 250.

Yamaha had not fielded a factory team since the 1957 Asama endurance race, when its machines easily trounced Honda in both the 125 and 250 contests.

In 1959 Yamaha acquired Showa. which was foundering. About half that company’s engineers, who had been intensively developing rotary valve technology, joined Yamaha. That year Yamaha built its first rotary valve two-stroke, an experimental model called the YX18. The company was too small to afford its own test course so the machine was tried out on a local bus driver training ground. Results were promising and by 1961 the machine had become the RA41. w hich Noguchi raced in France. This machine, an air-cooled Single, had two carburetors and two rotary disc valves, one on each side of the crankcase.

Why two rotary disc valves on a Single? Yamaha’s go-fast theory in those days was succinctly summed up by a company spokesman as “Fill as much gas as possible and make it explode.” That will do it. It did it for the RA41, which could hit 1 18 mph.

Ito’s 250 was the RD48. a rotary disc valve air-cooled Twin. The Yamaha was clearly influenced by MZ. with central drive and a disc valve to each crankcase.

The rotary disc valve, a solid disc attached to the end of the crankshaft, with an aperture that rotates past the inlet port, is a very precise way to control induction.

The Yamahas suffered numerous problems during their first European outing. Pistons seizures caused by poor cooling occurred repeatedly. There were problems getting efficient induction, combustion and discharge of the fuel/air mix at high revs. There were ignition problems. As with Honda, the design concepts were right, they just needed some reality modifications. So in 1962 Yamaha stayed home and did some engineering.

In 1963 the company was back with a redesigned 250, the RD56. and a new 125. the RA75—essentially half of the RD56. The RD56’s engine w'as basically the RD48 with detail changes, including anodized cylinders, stroke lengthened to 50.7mm, hemispherical combustion chambers, and enlarged exhaust ports, which raised peak reliable horsepower from 40 to 47 at 13,000 rpm. Frame and suspension were entirely new, designed with European circuits in mind.

The RD56s caused a sensation in Europe. repeatedly proving themselves faster than the Honda Fours—although not yet as reliable. Fumio Ito chased Rhodesian Jim Redman and his Honda home in the Isle of Man TT to grab second place, only about one mph down on Redman’s average speed over the whole race, despite the> Yamaha’s thirst for fuel. At one point in the race Ito was timed at 141 mph.

Ito was again on Redman’s heels in the Dutch TT for another second place, and at the Belgian GP in July he blasted away from the mighty Honda multis and not only ripped off the fastest lap of the race but cut 44 seconds from Bob McIntyre’s winning time on a Honda Four the previous year. Another Yamaha was in second place. It was a sweet victory.

And the high point of Fumio Ito’s racing career. At the Singapore Grand Prix the next year Ito. perhaps Japan’s greatest road racer, crashed w'hile pushing an RD56 to the limit. He suffered severe head injuries and never raced for Yamaha again.

Honda had another good year in 1962, winning the 125. 250 and 350cc championships.

The last class was new for Honda, was in fact the first time the factory had entered the 350 events. It was almost by chance they did. and the title extracted a high price.

When he noticed that the ruling Honda 250s were lapping faster than the European 350s, Bob McIntyre suggested an expansion. The team used the RC163, with bore increased from 44 to 47mm. That gave a displacement of 285cc and added three horsepower (49 at 14,000 rpm). The expanded RC163 w'as named the RC170.

At the Isle of Man TT that year Tom Phillis, who had placed third in both the 125 and 250 events earlier, lashed the new 285 to the limit trying to stay with MV riders Gary Hocking and Mike Hailwood, both of whom broke the 100 mph lap barrier in the 350 class for the first time in the Island’s history that day. The Honda couldn't keep up wfith the Italian machines and at Laurel Bank Phillis pushed too far, crashed and was killed. Two months later Bob McIntyre was killed.

In the wake of Phillis’ death Honda designed a new 350 machine, the RC171, with a displacement of 339.26cc. 50 horsepower at 12.500 rpm. and a wider powerband. This was strong enough to give Jim Redman the 350 championship, ending MV's four-year monopoly. The drive for racing dominance continued. For the 1963 season Honda dispatched yet a stronger 350, the RC172. which displaced 349.3cc and delivered 53 hp at 14,000 rpm. Satisfied with the performance of this machine. Honda ran it in the `63. `64. and `65 campaigns. rpm. enough to give Italian Luigi Taveri the title in 1964. But the 250 was a different story. Yamaha, continually tinkering with the RD56, had coaxed 56 horsepower out of the old design and in Phil Read had a pilot to match the best Honda could mount.

At the IM Read cut the fastest lap, coming within a hair of McIntyre’s record, but the Yamaha ate spark plugs and ultimately just didn’t have the stamina to stay with Redman’s Honda. The Twin’s engine finally seized at Bray Hill after Read had traded first and second with Redman for four laps. Redman went on to set a new race record. 97.45 mph. A water-cooled MZ motored to second place and set Yamaha designers to stroking their chins.

Honda did not officially sponsor a racing team in 1963. perhaps hanging back to see how' Yamaha would do. Still Redman won the 250 and 350 championships for the company. And Yamaha saw it was not enough to have the fastest machines. It w'ould have to find riders the equal of those Honda had. The company hired Englishman Phil Read and Canadian Mike Duff.

Suzuki took the 125cc championship away from Honda in 1963. Honda wanted victory in this class and the 250 perhaps more than it cared to defeat MV Agusta in the 350. Honda wanted to prove it was the best Japanese motorcycle maker, not only to the foreign market but back home, where most sales—usually lightweight— were still made. Honda was especially concerned with triumphing over old foe Yamaha. whose privateer machines were gaining a solid reputation in amateur meets throughout Japan.

At the end of 1963 Honda introduced a new four-cylinder 125cc machine, the RC146. which developed 24 hp at 15.000

On the shorter circuits on the continent the Yamaha’s superior power told and Read swept home first in five GPs.

At the Dutch TT Read was able to stay ahead of Redman most of the race, relying on superior acceleration to keep in front of the Honda, but Redman could easily outbrake the Yamaha. Into the corners he would shoot his machine past Read’s braking Tw in, waiting until the last fraction of a second before hauling the Honda down. On the straights Read w'ould sprint away again, gaining ten or more yards, only to lose them going into the sharp bends elbowing the course. In the last mile of the last lap Redman got by Read one final time to win by half a wheel. But it didn't happen that way often enough and Phil Read and Yamaha were 250 w'orld champions at the end of the season.

Honda realized such an outcome was inevitable once Yamaha got its machines sorted out. The only hope Honda had of getting more power was more cylinders. In the spring of 1964 the company began testing a new Grand Prix machine, the RC164. a six-cylinder 250. Equipped with a 7-speed gearbox this machine could rev to 19.000 rpm and hit 145 mph.

The Six w'as fast and powerful (58 bhp at 18.000 rpm), but the powerband was extremely narrow and, despite an 8-speed gearbox added for the '65 season, just couldn’t handle the by now thoroughly debugged RD56 and Phil Read—not to mention Mike Duff, who was usually right behind his teammate to ensure a Yamaha sweep. At the French GP Read finished six miles in front of the second place Honda.

In contrast to the less than successful debut of the Honda Six, Yamaha found it had real competition from the new Benelli Four. At the Spanish GP Read and Tarquinio Provini on a Benelli battled wheel to wheel, never more than one second apart for the whole race. The pace set by the two riders w'as so fast that by the 30th lap. with three more to go. they had lapped Duff on the other factory Yamaha. In a last lap bid to beat Read. Provini left his braking so late for a fast bend that he locked the front wheel and crashed.

But the real contest was undeniably between Honda and Yamaha. At the Isle of Man Redman won the 250 and 350 for the third year—the first time that had been accomplished—and Read’s Yamaha scorched off the first ever “over the ton" lap in the 250 race. From a standing start Read ripped through the first lap at 100.01 mph.

Read started 20 seconds behind Redman but made up 16 seconds on the flying Honda that first lap. New Yamaha rider Englishman Bill Ivy was also flying and to keep in front Redman pushed his screaming six to a new lap record of 100.9 mph, eclipsing Read’s just-recorded time. Then Read’s crankpin broke. Ivy crashed when mist clouded in at Brandywell corner and he surprised a slower man on his line. All wasn’t lost for Yamaha, however. Mike Dufif brought his machine home to second place . . . but minutes behind Redman's Honda. In the 125 class, on a brand new watercooled Twin never before raced, Read blasted 12 mph off the old record, averaging 94.28 mph in the process of trouncing Honda’s lightweight ace, Luigi Taveri. The machine he used was the RA97, which developed 28 bhp at 10,000 rpm and could safely rev to 14.000. The transmission-had nine speeds.

When it was working right the Honda 250 Six was the fastest thing on two wheels; at the East German GP Redman beat Read and his peak-performing RD56 by more than two minutes. It was clear to Yamaha that despite the astonishing riding of Read, Duff and Ivy, the Honda Six would eventually prove too strong for its roadster-based, air-cooled Twin. Yamaha won the 250 title in ’65 and Read and Duff were 1-2 in rider points but it was obvious the RD56 wasn’t up to making it three in a row in 1966.

Honda meanwhile, hard pressed by MZ in the 350 class and defeated by Suzuki in 125. knew’ it was time to multiply cylinders in those classes as well.

At the last European meet of 1965, at

Monza, Yamaha unveiled the RD05. successor to the venerable RD56. The RD05 was a water-cooled 80 degree V-4 wfith four overlapping rotary disc valves, an eightspeed transmission. 58 horsepower at 14.000 rpm, and a top speed of 150 mph. The motor was made up of two of the IoM water-cooled 125s hooked together, or so it appeared. But originally the V-4 had been air-cooled. The switch to water-cooling was made only when the mass of finning was shown to cause uncontrollable vibration. fuel foaming, frame cracking, and related ills. Both upper and lower crankshaft pinions drove a common transmission gear. Cylinders, heads, and flywheel assemblies w'ere separate. An impeller kept coolant circulating and banished heating problems (when it worked). The engine layout, with crankcases for two vertical cylinders mounted above those for two horizontal cylinders, meant a very high center of gravity and consequent bad handling; an unending nightmare for the engineers trying to solve the problem and for the riders who had to fight not only the track, the weather and other riders, but their own machines as well.

The new7 rocket fizzled at Monza, first refusing to fire and then sidelining Read during the race, w'ith minor ailments. Undeterred. Yamaha’s men modified the RD05 into the RD05A. The rotary valve timing was changed, horsepower w'as upped to 60 bhp at 14,000 rpm. CDI ignition was fitted and 50 extra pounds were pared away.

Honda knew' there would be competition in 1966. To meet it the larger firm mounted its greatest-yet assault on the worldclass titles. In 1965 Honda had seized the 50cc title from Suzuki, which had held> it since its inception in 1962. with a very slick machine, the RC115. a two-cylinder design delivering 15 horsepower at 21.000 rpm via a nine or 10-speed transmission. With a bit of tweaking it became the RC116 with peak power coming on at 21.500 rpm.

Honda hooked two and a half of these together to produce the RC149 five-cvlinder 125cc racer, with which it intended to reclaim the 125cc crown from Suzuki. The Five produced more than 34 bhp. could rev to 22 grand and had a top speed of 131 mph.

In the 250 class Honda’s Six was putting out a sustainable 60 horsepower at 18.000 rpm and had a much wider powerband than the first six. The RC173 350cc fourcylinder machine had power output boosted to 70 at 14.000 rpm. And for the first time Honda fielded a 500cc machine, the RC181. This monster Four delivered 85 horsepower at 12.000 rpm. That much power w'as more than its frame and swing arm could handle and Mike Hailwood, again racing for Honda, had his hands full riding it. Honda engineers seriously considered asking an Italian firm to build a frame for the machine.

Honda banzaied through 1966. Despite game efforts by Phil Read, who set the fastest lap in the Belgian G P. crashed while leading in the West German and won the Finnish, and by Bill Ivy, who won the Spanish. Dutch, and Manx 125 contests, w hen it was all over it was all Honda-and Hailwood. It seemed that every time and every place Mike the Bike raced, he won:

Spain, the Germanes. France. Holland. Belgium. Czechoslovakia. France. Ulster. Man. Italy; he won them all.

Some European marquesmen grumbled it wasn't Honda who beat them, it was Hailwood, who was individual rider champion in the 250. 350. and 500cc classes. Certainly there could be no question of Hailwood's riding genius, from his run and bump starting technique—jumping aboard sidesaddle he would rap the throttle wide open and with the engine at full shriek swing on board under full drasstrip acceleration like Tom Mix mounting some Star Wars version of a horse—to his deceptively graceful ballet-like progress at phenomenal speed around circuit after circuit. Time and again he finished minutes—and sometimes laps—ahead of his nearest competitor. In the 250 event at the Isle of Man he finished six minutes ahead of the second placing Honda. There can be no question that he was good.

But Yamaha hands knew that not only Hailwood, but undeniably Honda, had beaten them. Phil Read. Bill Ivy: they were a match for Hailwood. Ivy brought a 125 Yamaha home to first in the Spanish GP seven minutes faster than Hailwood ran the circuit on a 250 Honda. Phil Read on a 250 was second behind Hailwood in the Dutch TT. the Belgium GP. the East German GP. and the Czech GP. But the Yamaha V-4s handled far worse than the Hondas ever had. despite two steering dampers. Read continually had to second guess his mount into the corners and fight to stay aboard on the straights.

When the 1966 world titles were read off they were 50cc: Honda; 125cc: Honda: 250cc: Honda; 350cc: Honda; 500cc:

Honda. The company deserved as much credit for the fabulous accomplishment as its riders did. Yamaha had to be content with second place in the 125 and 250. as did Ivy and Read. But next year . . . next year. Just wait.

The next year was the beginning of the payoff for Yamaha. The company's 125cc was now a 9-speed V-4. a miniature '05A. putting out a solid 40 horsepower at 18.000 rpm. and incredibly fast. Ivy and Read traded firsts and seconds throughout the season to bring the 125 crown into the Yamaha camp for the first time. It was ironic that Ivy became champion rider in the class, for his machine never handled as well as Read’s—which was no dogcart pony—and he was thrown so often it became a joke.

The 250 V-4s were also fast. Read was able to win in the Spanish. East German. Czech, and Italian GPs. and Ivy in the French and Belgian, but it wasn't enough to hold off Hailwood and the wailing Honda Six. which was now pumping out something like 62 bhp at 18.000. The Yamaha had the power to cope with the Honda but handling was not improved; in fact it was so bad that at the Isle of Man Read's hands were blistered by the effort it took to hold the head-shaking two-stroke on course. Still Read managed to bring the viciously misbehaving, crash-bent Yamaha home to second place in one of the finest rides every witnessed.

In an attempt to control the evil tempered V-4 Yamaha engineers fitted a hydraulic diaphragm steering damper supplemented by a telescopic strut to the front wheel, and added an adjustable steering head, designed to vary rake. The steering head featured a pivot at the bottom rear. The bottom front was extended forward by a flat-sided block which pivoted between two parallel ears machined with slotted holes. Adjustment was made by fitting different width spacers between the upper rear of the head and the frame.

It was a nice try and it was successful on some of the smoother, less demanding GP circuits, but on the bumpy, twitching Manx course it just wasn’t enough to overcome the inherently poor handling of the topheavy Yamaha. The combination of 75 horsepower (from 249cc) and a three-inch tire was a handful on the demanding IoM circuit.

Mike Hailwood took the 350 championship on Honda’s ultimate GP racer, the RC174. a 297cc Six putting out 65-plus horsepower at 17.000 rpm. But in the 500cc tourney the RC181 Four was not quite up to the challenge of Agostini and the MV Agusta.

Bad handling still prevented the Honda from realizing the speed potential of its 85 horses. In '66 Hailwood dropped the Honda trying to keep up with Ago in the Dutch TT, and at the Belgian GP a week later Jim Redman, w ho was leading in 500 points, crashed pursuing the MV Agusta. was badly hurt, and never raced motorcycles again.

For 1967 Honda engineers tried a scheme to adjust trail, employing eccentric mountings to carry the wheel spindle, but had not gotten much improvement by season’s end. The 500 crown went to MV and Agostini.

Honda had had enough. Yamaha’s 250 was putting out over 15 per cent more power than Honda’s 350. At the Czech GP in the latter half of the season Hailwood's 250 Six lost 10 seconds a lap on Read's V-4 and despite determined riding by Hailwood, the Honda finished a humiliating third, more than a minute behind second place Bill Ivy’s Yamaha. The ululating, brain-piercing metallic scream of the Yamaha two-stroke multi sounded the doom of Honda’s four-stroke technology as surely as the how l of the Honda Fours only a half dozen years earlier had blasted aw ay old-order European engineering supremacy.

In the 500cc class MV Agusta w'as not a champion to be lightly unseated. In the smaller categories Suzuki and Yamaha were no longer challengeable: a four-cylinder DOHC sixteen valve 50. a six or eight-cylinder 125. V-12 250s and 350s. what would it take to match the twostroke’s power output? And what was to stop the two-stroke companies from playing Honda’s game and adding cylinders, too?

There was a limit and Honda had reached it. The company withdrew from competition. Mr. S had seen his name become a byword and his company become a legend throughout Europe and America. In nine years Honda scored 137 Grand Prix wins, including 18 Manx TT victories, and captured 18 manufacturer’s world championships and 16 individual championships. In 1966 alone Honda won 29 world championship races and five world championships. Mr. S could be satisfied.

After Suzuki announced it. too. would withdraw from the Grand Prix battleground. Yamaha thought it might as well follow suit, but then decided to allow its machines to race on, hoping to eclipse the glory Honda has won itself.

In 1968 Bill Ivy again won the 125cc championship for Yamaha, on a machine developing 325 bhp per liter, the highest specific output ever registered in that displacement. In the process he recorded the first ever over 100-mph lap on a 125cc machine at the Isle of Man. Ivy also won the 250ce Manx event, rocketing around the first lap at 105.51 miles an hour—from a standing start. That lap was miles an hour faster than the fastest lap Hailwood and the Honda Six had recorded the previous year.

But it was the Mt. Fuji climbing races all over again. Yamaha had the hardware to blow all comers—in particular Honda— into the weeds, but no comers were to be found. Now' that the company was getting a handle on its bike's steering problems, there was nobody in the same league with Yamaha.

After Yamaha stormed around the GP circuit virtually unopposable in 1968. the E1M decided things had gone too far. In a move meant to give the small European makers a chance, the organization outlawed the Yamaha V-4s. restricting future 125 and 250ec machines to two cylinders and six speeds.

One of the grandest eras in Grand Prix motorcycle racing history was over. It ended in default, by fiat. It was probably just as well. The speeds Yamaha and Honda found themselves capable of delivering were greater than the frame, suspension and tires could cope wfith.

That the machines, wicked handling, unwieldy and terrifically, frighteningly fast, did not kill in wholesale numbers the riders who dared force them to their maximum performance is the final, greatest tribute to the heroic skill of the young men who rode them; machines designed by equally young engineers half a world away, who had been given a blank checkbook and the instructions. “Make it go fast."El