MARUSHO: EXCELLENCE WASN'T ENOUGH

The rise and fall of a company which put engineering first, sales second

C.D. Bohon

Of the more than one hundred Japanese motorcycle companies that failed to survive until the great export boom of the 1960s, Marusho is the only one an American is likely to have heard of. Marusho was recently referred to as a classic in the CYCLE WORLD “Letters” column. There is even a Marusho Owners’ Club in Virginia and a company in California still stocks parts for the machine.

This said, we are left to wonder who or what Marusho was, what the bikes were like, and finally, what happened to the company with the unofficial slogan, “Engineering first, sales second.”

Masashi Ito, founder and president of Marusho, learned his trade under the guidance of Soichiro Honda back in the 1930s. Ito studied metallurgy at Honda’s auto repair factory in Hamamatsu, where he was an apprentice mechanic. After five years of Honda’s tutelage and a stint at another factory, Ito founded his own repair factory in 1940. He was 27.

It was an unfortunate time to establish a business. Two years later, with Japan at war, Ito was forced to sell his fledgling company. He was not able to get his company back in operation until 1946. Soon he was busy transforming cannibalized junkers of all makes into functioning motor vehicles. Ito’s reputation for quality work became such that he was hired by Toyota and Nissan to manufacture truck cabs. Ito and his company could have settled into prosperous obscurity but Ito has this thing about motorcycles—had always had it. He wanted to make his own. And he wanted to make the best.

So he sold his company and with the proceeds, on May 1, 1948 established the Marusho Motorcycle Manufacturing Company, Tokyo. The trademark of the new company told a lot about the philosophy of its founder. Maru is the same mam tagged on to the names of Japanese ships. It means “circle,” but it also implies wholeness and harmony. Sho means “right, correct, honest.” The Marusho logo was a circle enclosing the Chinese character for sho.

Marusho’s first factory employed 10 workers and built 30 motorcycles a month on order, cash in advance. These were distributed through Tokyo Toyota. These first Marushos, named Lilac, a flower Ito’s wife especially liked, were channel frame affairs not much different from the first Honda Dreams. Both the Honda and the Marusho were inspired by mid-1950s era German machines.

A typical early Lilac was the 1951 LB, a channel frame ohv Single displacing 147.9cc. The LB weighed 243 lb. and had a top speed of 49 mph. The engine produced 3.5 hp at 4500 rpm. The transmission was a two-speeder. Front suspension was handled by a telescopic fork, the rear was rigid. While the bike didn’t have the sophistication of the Honda Dream’s plunger rear suspension, admitted of having two less horsepower and weighing more, still it was faster than Soichiro’s machine and already boasted the Marusho specialty, shaft drive, a first in Japan. Every Marusho made would be shaft drive; Ito considered the chain a fragile, messy anachronism. The LC Marusho of the same period was equipped with an automatic transmission. The clutch plates were faced with cork, as in the early Hudson automatic transmission, upon which the Marusho gearbox was based.

In 1951 Marusho built 496 motorcycles, making the company the seventh ranking Japanese maker behind Honda, Meguro, Showa, Shin Meiwa, Rikuo, and Asahi. The next year saw Marusho drop the channel frame in favor of the tube frame, and adopt a plunger rear suspension for its 150. Factory output shot up to 2443 machines and Marusho took over fourth place among manufacturers.

In 1953 Marusho introduced its most popular model, the Baby Lilac, a 90cc runabout, a forerunner of the mighty host of lightweight utility step throughs with which Japan would flood the world in later years. For most of Marusho’s history the demand for the Baby Lilac would be greater than the factory could handle and the bike would always be back-ordered.

This little Lilac was an odd-looking machine, with the headlight and gas tank mounted as an integral unit, a wide-diameter, single-backbone girl’s bicycle-style triangular frame with double downtubes, oil tank hanging below the seat, bottom link forks almost Earlesian in size up front, and a rigid rear.

But the Baby’s 76 kilograms were propelled by an 88.6cc ohv engine delivering 3.2 hp at a time when most other 90s made do with 1.5 or 2 hp. It was a maintenancefree shaft-driver, the two-speed transmission was automatic, the carrying capacity was substantial. The rider was pampered by a luxuriously thick and soft seat in contrast to the bicycle seat other makers offered. The Baby Lilac even sported a tiny windscreen.

Sales of the Baby Lilac raised Marusho output to 6435 units.

In 1954, Marusho tooled up to build a completely different kind of machine, the Dragon. This was a horizontally opposed side-valve 350 Twin. It was equipped with swing arm rear suspension, and an Earles fork, starting a fashion in front suspension that almost every Japanese maker would succumb to eventually. The Dragon’s engine displaced 338.8cc and developed 11 hp at 4800 rpm. The transmission had three speeds. The bike weighed 417 lb. and had a top speed of 62 mph. With a solo seat and luggage rack, heavily valenced front fender and enclosed afterdeck, the machine was no beauty—and no runaway best seller.

Despite this, the next year was an optimistic one for Marusho, one in which the company looked to become a substantial manufacturer with a long-term prosperous future. Borrowing heavily from the Daiwa Bank, Marusho built a large modern factory in Hamamatsu. The 600 workers at the new plant built 90cc, 125cc, 250cc and 350cc motorcycles.

The most famous Marusho, as far as Japanese are concerned, was introduced in 1955. This was the SY250, an ohv Single. The company reverted to the telescopic fork and adopted plunger rear suspension in place of the swing arm of the 125 and 350. The SY and its descendants became the most popular shaft drive bikes in Japan, humbled Honda at Asama, were sent to China in one of Japan’s first motorcycle export bids, and are still fondly remembered in Japan today.

Mechanically, the SY was, well, restrained, with 8.5 hp and a top speed of only 62 mph. The lack of power wasn’t a serious drawback. If rival Tsubasa’s 250 had 12 hp, the DSK 13 and the Suzuki and Honda models 16, well, the Marusho would run forever. And somehow it looked right, sleek and slender with a thoroughbred air. Marusho’s 1956 250 was the UY, with beefier driveshaft, more power, softer and roomier seat and swing arm rear suspension. Who could want more than that?

Marusho fans got more anyway. At the first Asama Kogen factory endurance race held in November 1955, a Marusho SY250 piloted by 16-year-old Shiroo Ito trounced all comers, including the supposedly more powerful Tsubasa and DSK. Honda? Honda had gone all out to win, establishing a special training program for its riders. Honda prepared special bikes, and fielded 5 of 27 entries in the 250 event. Only one finished the race.

Marusho’s single stock entry went the distance, won the race, and brought giant killer status to Marusho, for Honda was already the second largest Japanese maker.

It was a thrilling victory for Marusho, but was not to be repeated. Marusho was simply too small a company to indulge in the expensive race program required to stay competitive.

Marusho sales reached a record 8091 in 1955, putting the company in sixth place, just behind Cabton.

In 1956 Marusho tried its hand at making a scooter. This long, low-slung vehicle was equipped with Marusho’s first twostroke engine, a 123cc Single turning out 5.5 hp. It was equipped with an automatic transmission. It had a bottom leading link fork. It didn’t sell. But a smaller version of the two-stroke went to power the Baby Lilac, still Marusho’s biggest seller.

Marusho sales, backed by an ad campaign proclaiming Lilac “The chainless motorcycle,” approached 10,000 but the company was gradually slipping out of the major contender class, dropping down to> eighth place among manufacturers as such new giants as Yamaha and Suzuki outbuilt and out-engineered it. The concept of a four-stroke Single was getting a bit dated, and even 10 hp was no longer enough from a quarter-liter machine when other 250s were delivering 18.

Ito said he had no other purpose in life than to make motorcycles

If Honda would sell to the Americans, Ito saw no reason why Marusho couldn't.

Ito considered the chain a fragile, messy anachronism.

Marusho decided to reinvigorate its whole line, starting with the venerable Baby Lilac. The concept of a shaft drive, maintenance-free, light utility machine was still good, and equipped with an upto-date two-stroke motor, plenty of power could be provided.

The Baby Lilac DP90, as the new bike was called, was powered by a 90cc (47 x 50mm) single cylinder two-stroke developing 5 hp at 5000 rpm. Most other Japanese 90s could do 55 or 60 kph. The new Baby Lilac could exceed 70. And it was competitively priced.

But the latest Baby Lilac didn’t sell. Perhaps it was too stark, too obviously an engineer’s concept of the ultimate in lightweight utility transportation. There was nothing on the machine that did not serve a purpose. There were no frills, no fakery, nothing but honest machine.

It was a beautiful machine in its way, but it was, as one Marusho freak recalls it, “not a fashionable motorbike. It looked too much the machine, especially for the ladies. They preferred the Super Cub, with its enclosed engine and weather protection.”

An equally stark two-stroke, the EN 125, met a similar fate.

The Marusho was substantially faster than any of its competitors. None were shaft drives, none looked so clean and straightforward—the Yamaha in particular looked especially ugly, although it sold well.

So what was wrong with the new Marushos? Or was it the machines that were at fault? Yamaha and Suzuki were backed by large organizations. Tohatsu and Honda had canny businessmen as well as engineers. Marusho was not backed by any large business relations, and the company and its president were not sales oriented. Ito really did seem more concerned with engineering than sales, and would reportedly stop the production line to make a minor modification that would rectify a problem which had appeared in bikes on the street, or to make some change which was not really necessary, although an improvement.

Japanese government pressure to rationalize the motor industry and reduce the number of manufacturers would also have serious effects on the company.

The CY250, which debuted in 1958, was the last of the 250cc Singles. The bike looked an awful lot like a Honda, with plenty of pressed sheet steel components, a bottom leading link front fork, and a bicycle seat mounted right up against the chromed gas tank. The 242cc ohv engine delivered 15.5 hp but the transmission still had only three speeds. Turn signals, front and rear, were standard.

The CY was a good try, as was its more Marusho-like brother, the FY, which had a tube frame and telescopic front forks, but the bike clearly showed its age in a fast changing motorcycle world: Honda had unveiled its 250cc C70. That twin cylinder wonder was capable of 18 hp.

Ito wasn’t about to be caught napping by his old master. Sales fell through 1957 and 1958, dropping to a little over 8000; Ito and company had some engineering to do.

Dawned 1959 and Marusho unveiled its first V-Twin, the Lilac CS28. Still lots of pressed steel but good handling telescopic forks, four speeds in the transmission. And a lovely 125cc 60-degree V-Twin motor developing almost 11 hp, delivered to the rear wheel by the now traditional shaft and spiral bevel gears. For power comparison, the 1959 Suzuki 126 produced 8 hp, the Yamaha 6.8. But Honda’s C92 put out 15 hp—at 9500 rpm. Oh, well, the Marusho handled better than the Honda. Marusho fans were satisfied.

Ito wasn’t. He went after Honda in the 250 class, and the machine he came up with made the Honda, in particular the C71, look positively stodgy. Japanese enthusiasts call Marusho’s masterpiece, the LS38, the best 250 built in Japan during the Fifties—or for years to come.

Not a scrap of pressed steel on the Lilac frame. Elliptical cross-section double downtubes cradled the engine. Telescopic forks handled suspension up front, a swing arm took care of the rear. The 3.00-18 in. tires were whitewalls. The light sports fenders were burnished aluminum. The seat was a luxurious bench type, or, on later models, a sporting solo. The rider’s knees gripped a beautifully sculptured racing tank. A tool kit was tucked in between the seat and the license mounting plate on the rear fender and supported a small luggage rack.

The engine, an enlarged version of the CS28 unit, was a jewel, producing 21 hp at 8000 rpm. The bore and stroke were square at 54 x 54mm. displacement 247.2cc. The compression ratio was 8.2:1. Both connecting rods ran on the same crankpin, like today’s Moto Guzzi V-Twins. Lightweight Duralumin pushrods permitted safe revs to almost 9000 rpm. A dry, single plate clutch engaged a four-speed constant mesh rotary transmission which had ratios of 5.43, 2.95, 2.22, and 1.69. The 353-lb. machine could exceed 85 mph, easily shutting down the Honda C71 and even the Yamaha 250S, a five-speed Twin with 18 hp on tap.

To add icing to the Lilac cake, the LS38 came equipped with an electric starter, neutral and third gear indicator lights, and turn signals with integrated warning buzzer—a first. The rear wheel could be removed by simply releasing the rear axle. The wheel hubs were full width and enclosed powerful single leading shoe brakes.

Not content with the power of the LS38, powerful as it was, Marusho unleashed the MF39 300 in 1959. This was the LS38 with the piston stroke lengthened to 62mm, and displacement upped to 288cc. Horsepower was increased to 23.5 at 7800 rpm. It was said that no motorcycle made in Japan could touch the MF in a speed or handling contest, with the usual exception of the limited production Hosk 500. A prone rider on the MF39 could see 90 mph without trying too hard.

As might be imagined, Marusho’s declining sales figures reversed and 1959 saw Marusho record its greatest sales ever, turning out 11,241 motorcycles and still leaving thousands of unsatisfied customers waiting in line.

In 1960 Marusho went after the 50cc mass market. Hoping to establish a broader manufacturing base, the company unveiled the A71, successor to the Baby Lilac. This was a fully weather-protected scooter powered by a 50cc, 4 hp two-stroke engine. An electric starter was fitted. The transmission was automatic. Top speed was 75 kph.

Renovating its whole line, Marusho also unveiled a sporting 125, the CF40, that was everything the LS38 was, only on a smaller scale. A stronger LSI8 250 also appeared.

Marusho sales were rising with every week that passed, thanks to this new range of V-Twins and the 50cc runabout, and the old plant in Hamamatsu just couldn’t handle any greater output. Ito made a decision, logical, necessary, perhaps a bit optimistic. He borrowed heavily to construct a new, larger plant. With the new plant, output would be raised to 27,600 units a year, more than double the 1959 record output.

Originally the plant was scheduled to be completed by April 1960. When it was not, the company found itself in a bind. Marusho was undercapitalized. The complete change of model line had cost heavily. The investment in the new factory had been a gamble based on hopes of doubled sales to keep the cash flowing. When this did not happen on time the company found itself short of cash as bills fell due.

Ito and his company faced an increasingly disastrous situation. Marusho’s bank, Daiwa, to which the company was deeply in debt for the plant loans, recommended that Marusho merge with Suzuki which, in its battle against Honda, would be glad to get Marusho’s four-stroke technology and engineering expertise. But Ito remembered his days as a Honda apprentice. The personal feeling of gratitude the Japanese maintain toward former superiors throughout a lifetime forbade Ito to accept Daiwa’s suggestion. He could not throw in with Suzuki.

Perhaps exasperated, Daiwa refused to loan the hard-pressed company any more money.

At this point Mitsubishi, whose Silver Pigeon scooter sales had begun to decline after 1958 and were seriously down by

1961, stepped in and offered to form ajoint venture company with Marusho for the production of the A71 under the Mitsubishi label of Girlpet. Mitsubishi promised to loan Marusho 300,000,000 yen to tide the company over and help retool.

Ito jumped at the offer. He needn’t feel he was betraying his old boss because the bank that is the heart of the colossal Mitsubishi combine had rescued Mr. Honda himself when his company had come a cropper in almost the same way Marusho had.

Counting on the promised Mitsubishi money, Marusho set about preparing its factory to produce 10,000 of the little Girlpet scooters each year. But Mitsubishi got cold feet. It dropped its targeted needs to 6000 scooters a year, then to only 3000. Mitsubishi actually handed over to Marusho only 50,000,000 yen of the promised loan. Then Mitsubishi backed out of the deal completely.

Ito and his company were staggered. He tried to rebuild the company, get the beautiful V-Twins, on which he had lavished so much talent and love, back in production and somehow save his company. But the dealer network Marusho had built up over the last decade refused, after the plan to distribute the A71 through Mitsubishi outlets, to handle Lilacs again. The company was stuck. Capitalized at 180,000,000 yen, the company owed 1,700,000,000 yen. On October 12, 1961, Marusho Motorcycle Manufacturing Company was declared bankrupt.

That should have been the end of Marusho, and the marque should have disappeared, leaving no more trace on the American motorcyclists’ consciousness than did half a dozen other Japanese companies which failed about the same time. But Ito wouldn’t give up. By January

1962, he had gotten his company a berth as a subcontractor for his old boss Honda, and set about paying off the company’s debts.

In the early Sixties a new idea was sweeping the Japanese motorcycle industry: Export! Previous to this Japanese companies had assumed that their machines were simply too inferior to compete with foreign motorcycles in the world market. But Honda had proved this idea mistaken, and the saturated home market was shown not to put a limit on manufacturing. Ito saw no reason why, if Honda would sell to the Americans, Marusho couldn’t. His company could be revived and go on to even greater heights.

In 1963 the Lilac rose phoenix-like out of its economic ashes when the C82 was put in production.

But the C82 was only a stopgap. Ito studied the American market. In 1964 he went to Los Angeles to check out the American scene in person and discover what the American rider wanted. Ito found 500cc motorcycles selling for about $ 1000. He calculated his factory could turn out 100 500cc machines a month and sell them with a small profit at $530 each.

The fact that Marusho didn’t have a 500cc motorcycle and had never built one didn’t bother him. Marusho could make a 500 and a good one, too. That was not the problem. Money was. While in Los Angeles, Ito, totally unfamiliar with the ways of American business and finance, made an agreement with Matsusushi, a Japanese restaurant, to act as his agent in the U.S.

Ito had said that he had no other purpose in life at the time than to make motorcycles. Perhaps it was this fascination with his machines that blinded him to the long odds against his plans. But still he tried. He talked to his creditors and attempted to convince them that if they would back him once again he could export his new machines to America and easily repay his company’s debts.

While this was going on Marusho designed new bikes, started production, and began to export. Ito’s agreement with Matsusushi specified numbers and dates. Marusho had a deadline to meet.

For the design of the new 500, Marusho went back to the layout of the old Dragon 350, and came up with a horizontally continued on page 94 opposed Twin, the R92, called the Magnum in the U.S. This Lilac was first built in 1964 and had a bore and stroke of 68 x 68mm. identical with the BMW R50. It is fairly obvious Marusho was influenced by the Bavarian, but bore and stroke don't necessarily reveal relationships. The Laverda and Yamaha 750 Twins of the Seventies share bore and stroke dimensions, yet are scarcely copies of each other.

lí you’ve got a Marusho, keep it. If you can find a Marusho, buy it.

continued from page 79

In any event, the 493cc R92’s engine pumped out 36 hp at 6500 rpm. The BMW R50 was a slug by comparison, producing only 26 hp at 5800 rpm. Handling of the R92 was quite good. Top speed was 100 mph.

In 1965 Marusho started production of its biggest V-Twin. aimed specifically at the American market. This was the Lilac M330. a redesigned model with a bore and stroke of 58 x 63mm. Perhaps haunted by a desire to cut costs, initially neither the R92 nor the M330 was equipped with an electric starter, previously standard on all Marushos.

These final Marushos were well-designed machines but in the rush to get machines out of the factory and sold quickly, assembly was often sloppy, as was the manufacture of parts. There was no rubber boot shielding the connection of the driveshaft with the transmission on the R92 and road dirt and water had free access to the rear hub and gears. A drain plug was supposed to be fitted, but often was not. Some machines had oil filters, others did not. The spiral bevel gears used in the final drive, made by Brother Industries (the sewing machine and typewriter people), were substandard and 20 percent had to be rejected by Marusho. These gears on R92s running today are usually pitted and in poor condition.

Both the M330 and the R92 were really only stopgap machines built to get the cash flowing and the company back on its feet. Ito had more advanced designs on his mind for future Marushos. We can gain some idea of Ito's thinking by looking at two Marusho prototypes built in 1964. the Lilac 103 series.

These were both horizontally opposed overhead-camshaft Twins, one a 125cc producing 14.8 hp at 11.000 rpm, and the other a 160cc machine developing 16 hp at 10.500 rpm. Equipped with 5-speed transmissions the bikes could reach 80 and 85 mph, respectively.

While Marusho was busy designing, building, and exporting, the company’s creditors decided they were not impressed with Ito’s arguments. They demanded immediate repayment of all debts, telling Ito that if his company had enough money to build and export motorcycles it had enough to pay them.

Suppliers demanded cash in advance before selling material to the Marusho> factory. Without a single dealer handling the marque in Japan, prospective buyers had to come to the factory to pick up their machines. Not the best way to make volume sales.

On top of this the first Marushos arriving in the States had teething problems, as well they might, considering the rush in which they were made. Ito himself flew to L.A. to make them right.

Despite determined efforts, Marusho was not able to deliver the required number of bikes to Matsusushi in the time specified by their agreement. Matsusushi’s bank refused further financial backing, pulling the rug from under Marusho on the American side. It was the final straw. Ito had lost the toss and Marusho was dead, despite a game fight to resurrect it. The year was 1966.

Back in Japan Ito put the company’s affairs in order and withdrew into retirement, after saying goodbye to the remaining 30 employees on the Marusho payroll. Almost all his personal funds—and his wife’s—went to pay Marusho creditors.

Reorganized and headed by one of the remaining employees, Marusho is still in business, working to repay the accumulated debts yet outstanding. It has nothing to do with motorcycles.

Ito spent his time in retirement bowling, a new fad in Japan then, and playing golf, sometimes thinking about how close he had come to saving his company. If only he had had better financial backing ... if only the Japanese government hadn’t squeezed small manufacturers ... if only he had taken up the Suzuki offer ... if only . ■ .

if you’ve got a Marusho, keep it. If you can find a Marusho, buy it. The motorcycle named for a flower represents the special vision of one man and his small company, dedicated to the motorcycle as an ideal and firmly pledged to making what they sincerely believed were the best motorcycles in the world. [Q!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

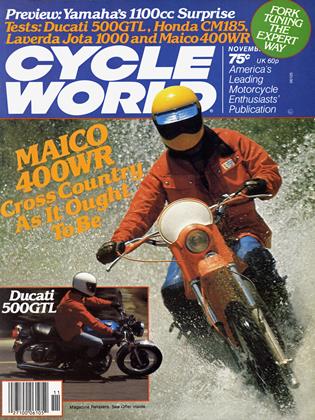

Up FrontSelling the Sizzle

November 1977 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1977 -

Departments

DepartmentsService

November 1977 By Len Vucci -

Features

FeaturesToo Much Government Is In Our Future

November 1977 By Lane Campbell -

Features

FeaturesItalian Spoken Here

November 1977 By Jean Crabb -

Roundup

RoundupThe Victory Continues

November 1977