ossa

An Innovative,Young Company Gives the Big Boys a Lesson.

GEOFFREY WOOD

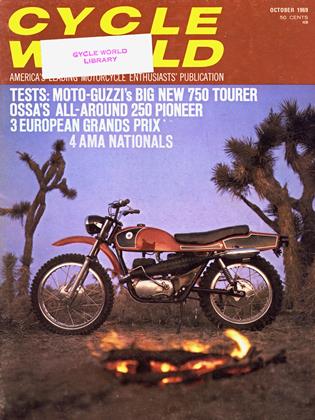

OSSA is a relative newcomer to the international motorcycling scene, but, in just four years, this Spanish marque has established an enviable reputation among the world’s sporting-minded riders. The story of this innovative concern is a fascinating tale of remarkable men who love the sport, and they, perhaps more than the technical excellence of their wares, are a most interesting aspect of Ossa’s history.

The story of Ossa actually began in 1924, when Manuel Giro bought an American-made Cleveland 270-cc twostroke Single. Giro quickly fell in love with motorcycling. Even today, the 61-year-old company boss thinks in terms of two wheels and an engine— especially in its more sporting forms.

Giro spent the early 1920s as a merchant marine officer. After he married, he founded his own small business, and raced motorboats in his leisure time. His company, Orpheo Sincronic, S.A., produced movie projectors and related types of cinema equipment. The name “Ossa” was later to come from the initial letters of the words in this company name, but that was in the future.

The innovative genius of Señor Giro was first demonstrated in his boat racing activities. He designed his own engines, named Soriano, and these outboard motors powered him to several world speed records.

Giro’s interests soon returned to motorcycles, however. In. the early 1930s, he purchased an ES2 model Norton, an outstanding bike for the time. The ohv 500-cc thumper, with its hand-shifted, four-speed gearbox, carried Giro about the Spanish countryside in regal style. By then, his tiger instinct had developed, so Giro decided to race. Luck was with him, for he convinced Norton ace Pejxy Hunt to sell him his works ohc CSl model after the Spanish Grand Prix. The pukka racer had a rigid frame, foot-shift cog box, and 100-plus-mph performance—as well as a reputation for winning races all over Europe. The beastly power proved to be the undoing of Giro. He proceeded to slide down the road on the seat of his britches in the six or seven races he entered.

During the middle 1930s, Giro changed to a 500-cc BMW Twin, but this underpowered model didn’t improve his race record. The answer was more power, so he mounted one of his Soriano outboard motors in the BMW chassis. The six-cylinder ohc Soriano powerplant displaced 998 cc, and had a big, wicked looking supercharger.

The power output was a devestating 112 bhp at 6000 rpm—nearly three times that of other bikes. But the old BMW had a rigid frame and girder front fork—hardly equipment to hold 112 bhp steady down a winding stretch of road! The result usually was a searing screech of rubber laid down each straight, followed sooner or later by a crash at a corner.

After this unsuccessful racing career on two wheels, Giro turned to the sidecar class and won a Spanish championship. Then Giro concentrated on expansion of his cinema enterprise, which today produces 80 percent of all Spanish movie projectors. His final fling at the motorbike game before World War II was the designing and building of a 125-cc single-cylinder prototype. Giro later gave this engine to Montesa. He now ruefully recalls that this engine powered the first road racing Montesa to many Spanish championships.

After the war, Giro’s primary interest was to design and produce a good motorbike. He was motivated by his affection for motorcycle sport, and the excellent business opportunity that existed then. In the late 1940s, Spain was entering an era of increased affluence because of the industrialization and irrigation of the country. Thus, the people could park their burros and begin to ride motorbikes.

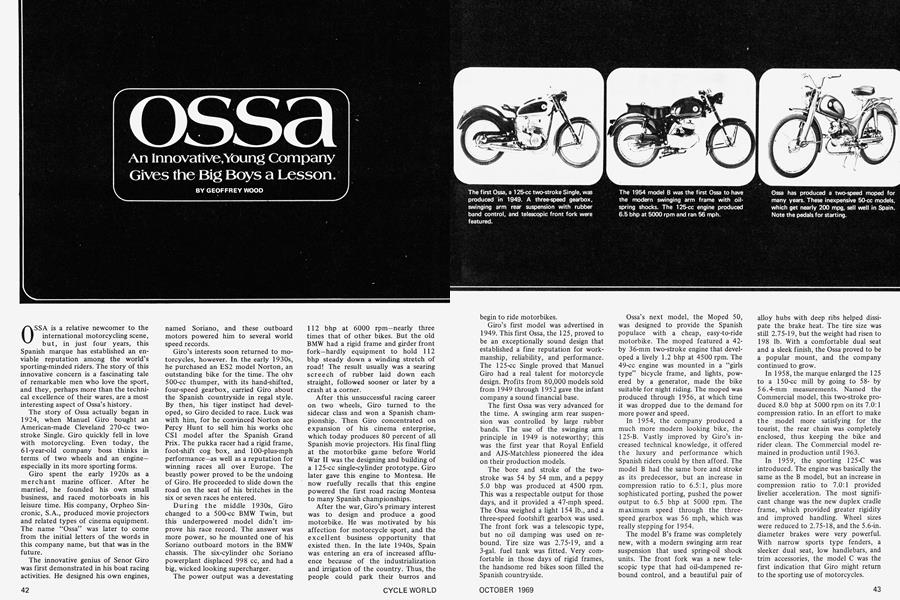

Giro’s first model was advertised in 1949. This first Ossa, the 125, proved to be an exceptionally sound design that established a fine reputation for workmanship, reliability, and performance. The 125-cc Single proved that Manuel Giro had a real talent for motorcycle design. Profits from 80,000 models sold from 1949 through 1952 gave the infant company a sound financial base.

The first Ossa was very advanced for the time. A swinging arm rear suspension was controlled by large rubber bands. The use of the swinging arm principle in 1949 is noteworthy; this was the first year that Royal Enfield and AJS-Matchless pioneered the idea on their production models.

The bore and stroke of the twostroke was 54 by 54 mm, and a peppy 5.0 bhp was produced at 4500 rpm. This was a respectable output for those days, and it provided a 47-mph speed. The Ossa weighed a light 154 lb., and a three-speed footshift gearbox was used. The front fork was a telescopic type, but no oil damping was used on rebound. Tire size was 2.75-19, and a 3-gal. fuel tank was fitted. Very comfortable in those days of rigid frames, the handsome red bikes soon filled the Spanish countryside.

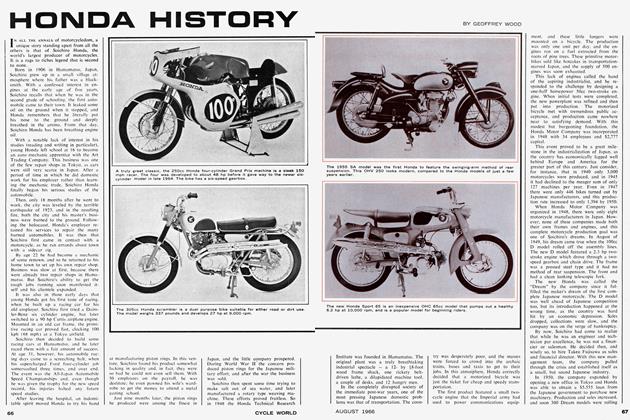

Ossa’s next model, the Moped 50, was designed to provide the Spanish populace with a cheap, easy-to-ride motorbike. The moped featured a 42by 36-mm two-stroke engine that developed a lively 1.2 bhp at 4500 rpm. The 49-cc engine was mounted in a “girls type” bicycle frame, and lights, powered by a generator, made the bike suitable for night riding. The moped was produced through 1956, at which time it was dropped due to the demand for more power and speed.

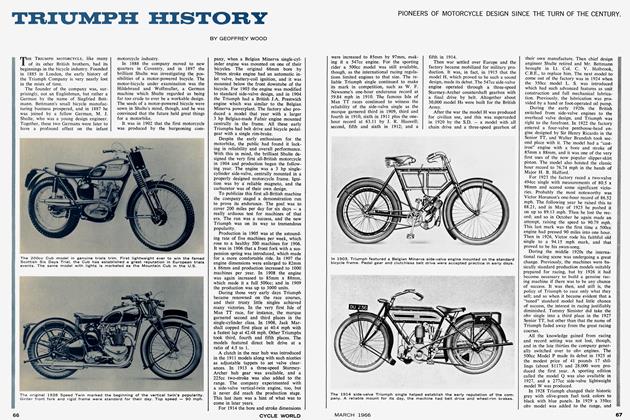

In 1954, the company produced a much more modern looking bike, the 125-B. Vastly improved by Giro’s increased technical knowledge, it offered the luxury and performance which Spanish riders could by then afford. The model B had the same bore and stroke as its predecessor, but an increase in compression ratio to 6.5:1, plus more sophisticated porting, pushed the power output to 6.5 bhp at 5000 rpm. The maximum speed through the threespeed gearbox was 56 mph, which was really stepping for 1954.

The model B’s frame was completely new, with a modern swinging arm rear suspension that used spring-oil shock units. The front fork was a new telescopic type that had oil-dampened rebound control, and a beautiful pair of alloy hubs with deep ribs helped dissipate the brake heat. The tire size was still 2.75-19, but the weight had risen to 198 lb. With a comfortable dual seat and a sleek finish, the Ossa proved to be a popular mount, and the company continued to grow.

In 1958, the marque enlarged the 125 to a 150-cc mill by going to 58by 5 6.4-mm measurements. Named the Commercial model, this two-stroke produced 8.0 bhp at 5000 rpm on its 7.0:1 compression ratio. In an effort to make the model more satisfying for the tourist, the rear chain was completely enclosed, thus keeping the bike and rider clean. The Commercial model remained in production until 1963.

In 1959, the sporting 125-C was introduced. The engine was basically the same as the B model, but an increase in compression ratio to 7.0:1 provided livelier acceleration. The most significant change was the new duplex cradle frame, which provided greater rigidity and improved handling. Wheel sizes were reduced to 2.75-18, and the 5.6-in. diameter brakes were very powerful. With narrow sports type fenders, a sleeker dual seat, low handlebars, and trim accessories, the model C was the first indication that Giro might return to the sporting use of motorcycles.

The model C was followed in 1960 by the model C-2, which was a refinement of its predecessor. But the next model introduced was a real innovation; Ossa left the two-stroke field and produced its first four-stroke model. Called the Gran Turismo model, the new 175-cc Single had a bore and stroke of 60 by 61 mm. The power output on the 8.3:1 compression ratio was 12 bhp at 7000 rpm, which provided a speed of 75 mph. The engine and the new fourspeed gearbox were contained in one case. The gearshift lever was mounted on the right side, the opposite of previous practice.

The Gran Turismo’s frame also was unique in that it resembled so closely the famous Metisse frames produced by the Rickman brothers in England. The GT model was produced as a sports mount, and its large alloy engine finning, 22.5-mm carburetor, 160-mm brakes with an air scoop on the front brake, and sports fenders, seat, and handlebars made it popular with pseudo-racers in Spain. The 242-lb. weight gave the GT a stable feeling, and it soon became known for its fine handling and powerful brakes. The GT was produced through 1963, at which time it was dropped from production. The marque evidently felt that the two-stroke had a better future in Spain, since its production cost was lower.

During the middle 1960s, Ossa sales suffered because, by that time, more Spanish people could afford to purchase small cars. But the firm benefited from the arrival of Eduardo Giro, Manuel’s 28-year-old son. Eduardo is a natural engineering genius, and it is he who is responsible for the current success of Ossa in sales and competition all over the world. Eduardo first demonstrated his talents at age 15, when he designed and built an 18,000-rpm model airplane engine. Since then, this studious young man has applied himself to motorcycle design.

Eduardo’s first designs were the 160 and the 160 Turismo-both 160-cc models with a bore and stroke of 58 by 60 mm, a compression ratio of 8.5:1, and a power output of 10.3 at 5750 rpm. The only real difference between the engines was that the kickstarter and gearshift were on the right side on the 160 and on the left side of the Turismo model. Both models had four-speed gearboxes and ran 65 mph, and both models featured powerful 40by 158-mm brakes. The 160 had the air scoop on the front brake on the right, while the Turismo had the scoop on the left. They are still in production.

By 1965, it was obvious that Ossa would have to develop an export business if it were to survive the decreasing demand in Spain. At that time, Ossa was little known outside of Spain. The problem was how to become known all over the world, and the answer was not long in coming. With Manuel’s love of racing, plus the technical genius of Eduardo, the only logical approach was competition.

With this in mind, Eduardo designed the prototype model, which was to compete in the classical Barcelona 24-hour race. This great endurance event is for standard production models, although there is some leeway in the rules for prototypes by the factories. Since a team of two riders takes turns for the full 24 hours, the bikes must have full lighting equipment. The exhaust systems can be modified for more power, but pukka racing models are not allowed. The idea is to race standard production models with only those modifications that a private owner could make, and the premium is on reliability.

The bike that Eduardo designed was a 175-cc Single with a bore and stroke of 60.9 by 60 mm. The compression ratio was a rather high 11.5:1, and the power output was 19 at 7200 rpm. The fourspeed gearbox was shifted from the left side, and 2.75-18 tires were mounted on alloy rims.

The optimistic factory entered a pair of these prototypes in the Barcelona classic, and they garnered a 1 st and 2nd place in the 175-cc class over the highly favored Bultacos and Montesas. Pedro Millet and Luis Yglesias racked up a total of 584 laps in the 24-hour grind, compared to 631 for the winning Dresda-Triton (650 Triumph in a Manx chassis) and 559 laps for the fastest 175-cc Montesa.

The Ossa managers were so enthused by this stunning upset that they decided to enter a foreign race, the British 5 00-miler at Thruxton. The MilletYglesias team came home 6th in the 250-cc class on their 175 Single. These two fine showings in 1965 made Ossa better known throughout Europe, and created a new demand for the machines in the export market.

Ossa was quick to take advantage of its newfound reputation in 1966 by producing the 175-cc model for export. The new Single featured a 27-mm carburetor and pumped out 21 bhp at 7500 rpm, good enough for a top speed of 85 mph. The gearbox had ratios of 15.9, 10.7, 7.97, and 6.51:1. Dry weight was a light 207 lb., and wheelbase was a short 52.5 in. With powerful brakes, extra fine handling, and outstanding performance, these Ossas made many friends around the world. The 175 is still in production, but very few made their way to this country in 1966.

In 1966, the company again had a bash at the classical Barcelona event, this time with a new 230-cc prototype model. The marque did quite well, taking a 3rd in the 250 class behind Montesas, and a 5th overall with two Montesas, a 500-cc Velocette, and a 650-cc Triumph ahead of Yglesias and Petras.

This fine performance brought the company more publicity, and the company responded by producing the 230-cc model for 1967. The new Single had a bore and stroke of 70 by 60 mm, a compression ratio of 11.0:1, and a 32 mm-carburetor. Peak power was 25 bhp at 7000 rpm, which provided a speed of 87 mph.

This rugged engine was mounted in an excellent duplex cradle frame, and a Telesco front fork provided 4.75 in. of travel. The accent of the 230 is definitely sporting, with such features as a knee-notched 3.9-gal. fuel tank, narrow sports fenders, sports seat, low handlebars, high performance exhaust system that pushes the noise level to the legal limit, and powerful brakes, as effective as they are beautiful. The wheelrims are alloy, and the tire size is 3.00-18. The 2 30 became popular with sportingminded street riders all over the world, and the export market flourished as never before.

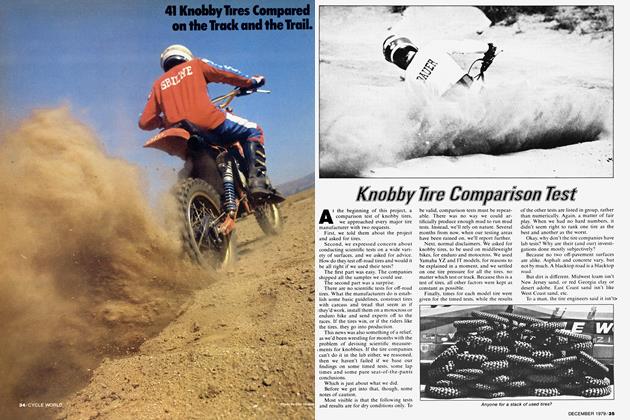

In 1967, the company increased its activity in the production model racing game to a fever pitch, partially because of its desire to become better known, but also because of increased interest in this type of racing throughout Europe. The model used was the already proven 230-cc Single, modified by using the optional race kit that anyone can now purchase for this model. The kit includes such goodies as an expansion box exhaust system, huge 5-gal. fuel tank, racing seat, tachometer, racing tires, clip-on bars, and a rearset footpeg-gearshift-brake kit. With the kit installed, the Ossa is a kissing cousin to a pukka racer, and the top end is pushed to over 100 mph.

The first big event that year was the first of the Isle of Man production model TTs. The lone Ossa entry, in the hands of Trevor Burgess, got off to a poor start when the kickstart lever broke on the starting grid. Trevor eventually got away in last position, but managed to finish 11th at 77.98 mph, which was over 10 mph slower than the Bultacos.

The other big event in 1967 was the rugged Barcelona classic, and the Carlos Giro-Luis Yglesias team gained the marque a tremendous amount of prestige when they romped home the winner over all the big bikes entered. Ossa also took 1st and 2nd in the 250-cc class, and its 662 laps in the 24 hours is still the record for this great race. This stunning victory brought the marque a great deal of publicity, and the export market continued to grow.

In 1968, the company expanded its roadster range by offering new 160and 175-cc models in both touring and sports trim. The 160 Sport pumped out 10.3 bhp and ran 65 mph, while the 175 SE model developed a wicked 21 bhp and ran 87 mph. The 50-cc moped also was produced, mainly for the European market.

In 1967 the company made a significant move in entering the rough-stuff game by producing trials, motocross, and enduro models. All of these models use the new 250-cc (60by 72-mm) engine, but differences in tune distinguish them. The trials model, for instance, runs on a 9.0:1 compression ratio and develops 16 bhp at 6000 rpm. Carburetion is by a small 24-mm carburetor, and an extra wide ratio four-speed gearbox is used. The motocross model uses a 33-mm carburetor on a 12.5:1 compression ratio, and it pumps out 32 bhp at 7000 rpm. The enduro model runs on an 11.0:1 ratio and develops 20 bhp at 6800 rpm. The enduro model is equipped with lights, and is produced especially for the American market.

The trials model has been fairly successful in European events, winning a Gold Medal in the 1967 International Six Days Trial in the hands of Englishman Mick Andrews. The British ace also gained the marque great recognition by taking 3rd place in the 1968 Scottish Six Days Trial. Other Ossas placed well throughout the field.

In 1968, the company once again featured prominently in the international production machine racing game. Ossas took 4th, 5th, and 7th in the Barcelona grind, as well as 2nd, 3rd, and 4th in the 250 class. Perhaps the marque’s greatest hour came in the IOM production class TT, when Trevor Burgess trounced the 250-cc field on his 230-cc thumper at 87.21 mph. This speedy performance would have given him a 4th place in the 500 class and a 6th in the 750-cc class—not bad for a 230-cc Single with a bolt-on kit!

This success in production model racing and trials competition brought the company a further boost in prestige and export sales, but to the brilliant Eduardo this was not enough. Eduardo believes the greatest glory is reserved for the fire-breathing grand prix machines, and that success in this field is the very summit of achievement for an engineer. With this in mind, Manuel gave his son his blessings to produce a genuine grand prix racer.

Eduardo began the design work in 1966, bearing in mind that his small company could not afford to finance exotic multis or a vast works team. The goal was maximum performance on a modest budget; Eduardo chose the trusty old single-cylinder design.

By late 1966, the engine was completed and on the test bed, and early in 1967 the completed bike was given its first test runs. The specifications of the Ossa GP are rather unique, and technical aficionados are fascinated by it. The engine features a rotary valve, since Eduardo found that a disc valve would better charge the crankcase than a conventional piston-controlled port. The exhaust system must be the largest expansion box ever built, and the gearbox is a six-speeder. Ignition is by a unique transistorized setup, and the engine finning is immense.

The frame is totally unorthodox with its monocoque chassis. Made from alloy sheet, the frame is extremely light, yet very strong. Probably the most unusual specs were the oleo-pneumatic front and rear suspension units, throwbacks to the old KTT Velocette air-oil shocks. The advantages are that the air pressure and/or oil flow can be quickly adjusted to suit local track conditions, and the large reservoir of oil does not overheat or aerate—thus changing the suspension characteristics during a race.

With an impressive 45 bhp on tap, the Ossa is considered the fastest 250-cc two-stroke Single on the grand prix circuit. The new Ossa’s first race was the 1967 Spanish GP, in which Carlos Giro took the bike to 6th place. More work obviously was needed.

In 1968, the GP model reappeared in the hands of 1967 and 1968 Spanish 250 champ Santiago Herrero. Many minor changes had been made to improve the handling, suspension, and reliability. The first race was the German event at the Nurburgring, where Santiago took a 6th place. In the Spanish GP over the twisty Barcelona circuit, Santiago actually led the 70-bhp Yamaha V-4s until his engine blew, but Carlos Giro saved company honor by finishing 4th. By then, the racing world was astounded at the sheer speed of the disc-valve Ossa Single.

In the famous TT races, the Spanish ace could fare no better than 7th, but the 37.75-mile island course does take a bit of learning. In the timed section on the drop to Sulby, the Ossa was clocked at a cool 121.6 mph, the fastest by a single-cylinder 250 in the race.

Santiago then proceeded to take a 6th in the Dutch, 5th in the Belgian, and a 3rd in the Monza GP. Despite missing several races that season, Santiago finished in 7th position in the 250-cc World Championship, and Ossa garnered 4th in the manufacturers’ championship. In races he finished, Santiago was never headed by another single-cylinder model.

And so ends this tale of Ossa—a story of fascinating personalities, brilliant engineering on a modest budget, and a typical Spanish love for competition. Currently one of the most interesting makes on the market, the Ossa surely must have a great future ahead of it in international motorcycle sport. Unknown until recently in this country, the company nevertheless has a colorful history that began when Manuel Giro pointed his Soriano-BMW down that winding Spanish road. A rigid frame, 112 horsepower, and a girder front fork—the screeching of rubber and then a horrible crashing of metal. That was just the beginning.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

OCTOBER 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

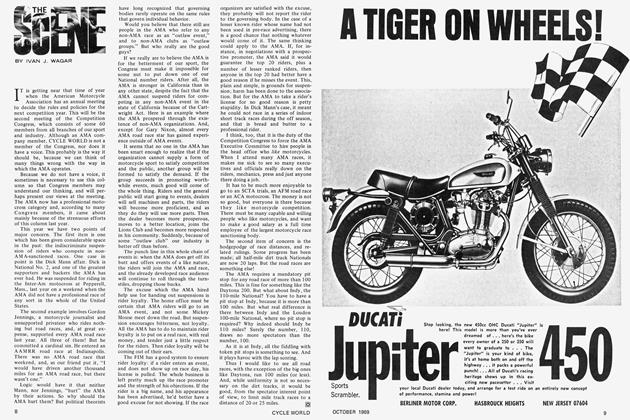

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

OCTOBER 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Service Department

OCTOBER 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

OCTOBER 1969 -

Competition

CompetitionAll-Bike Drags At Lions the Big Guns Share A $1500 Purse.

OCTOBER 1969 By Dan Zeman -

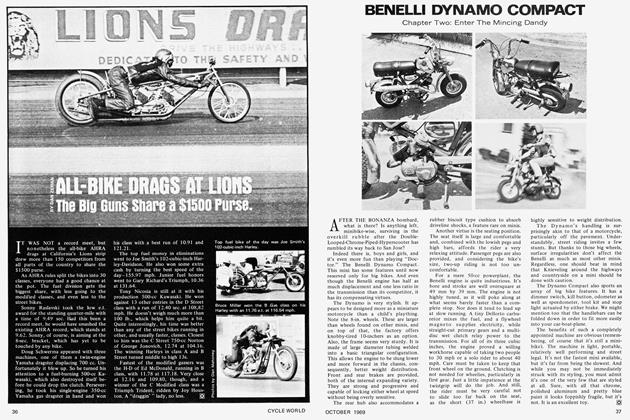

Tests

TestsBenelli Dynamo Compact

OCTOBER 1969