THE REDOUBTABLE NORTON

Geoffrey Wood

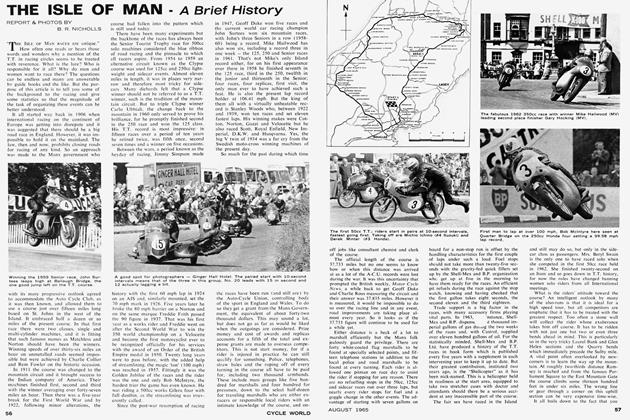

JAMES NORTON started his company very humbly in 1898, but it was not to stay that way for long as the name was destined to become the very symbol for excellence in motorcycle design. Winner of 34 TTs, many hundreds of major Grands Prix, and literally thousands of local races all over the world, the Norton is certainly the greatest name in the history of motorcycle racing.

Born in 1869 in Birmingham, England, James Lansdowne Norton was one of the truly great pioneers of the motorcycle industry. For the first twenty-five years of this century his genius at engineering and production methods helped put the British industry at the very top, and when he died in the spring of 1925 his company was destined to help carry on British supremacy of international sales and racing competition throughout half the century.

Norton launched his little company in 1898, and for the first few years he concentrated on making a 1-1/3 hp engine, and a host of proprietary parts for other motorbike manufacturers. Norton did not build his own engines in those early days, but relied instead on the French Clement, the Moto-Reve from Switzerland, and the V-twin French Peugeot. It was on one of the latter that Norton scored their first TT win, with Rem Fowler up in 1907 in the twin-cylinder class.

"Pa" Norton was hard at work on his own engine design though, and in 1908 the "Big Four" was introduced — a single of 633cc with a bore and stroke of 82mm x 120mm. This side-valver was later stable-mated with a 500cc model with measurements of 79mm x 100mm — measurements which were to become legend with Norton.

These early thumpers proved very popular. They were one of the most reliable motorbikes on the road, and so the reputation of Norton was sealed. The models were steadily improved, and several gearboxes were tried as Norton was a great advocate in those days of two and threespeed countershaft gearboxes. All this, remember, was at a time when nearly everyone else used only a single speed belt drive.

It was apparent to James Norton that the real future lay with the overhead valve engine design, and in the years just prior to World War I he drew up the plans for his new OHV engine. The factory still relied on their 500cc side-valve models for racing after the war, however, for it would take a few years to prove the merits of the new engine. The 1920 side-valve TT machine was no slow poke either; it was by then capable of 75 mph at 4,300 rpm on its 5.25 to 1 gear ratio.

In 1922 the OHV engine was given its first airing, and the 500cc model retained the same 79 x 100mm measurements of its forebearer. in 1923 the new model hit the headlines with two records: the one hour mark at 82.67 mph, and the flying kilometer at 89.22 mph. From then on the OHV engine was used exclusively for racing, although the side-valve model stayed popular many years as a roadster.

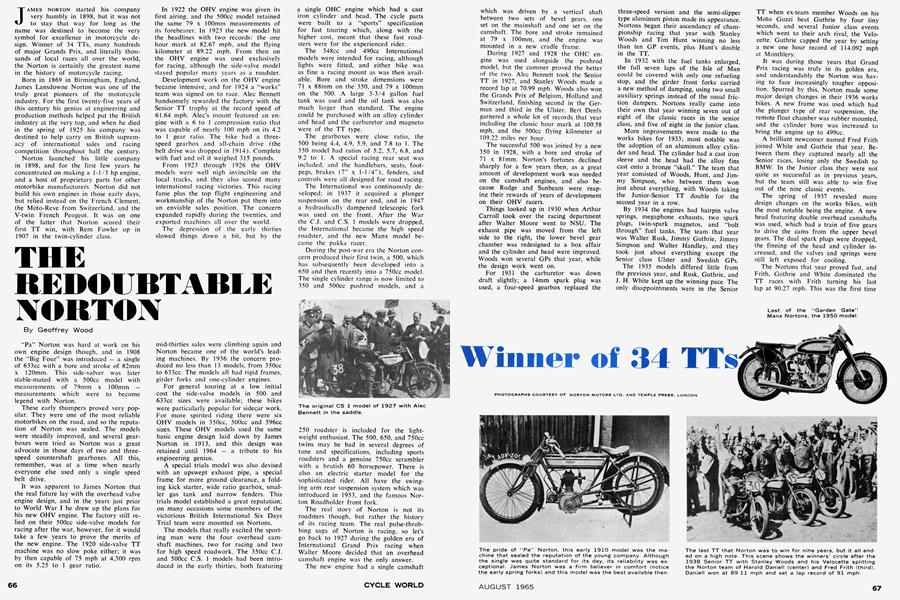

Development work on the OHV engine became intensive, and for 1924 a "works" team was signed on to race. Alec Bennett handsomely rewarded the factory with the Senior TT trophy at the record speed of 61.64 mph. Alec's mount featured an engine with a 6 to 1 compression ratio that was capable of nearly 100 mph on its 4.2 to 1 gear ratio. The bike had a threespeed gearbox and all-chain drive (the belt drive was dropped in 1914). Complete with fuel and oil it weighed 315 pounds.

From 1923 through 1926 the OHV models were well nigh invincible on the local tracks, and they also scored many international racing victories. This racing fame plus the top flight engineering and workmanship of the Norton put them into an enviable sales position. The concern expanded rapidly during the twenties, and exported machines all over the world.

The depression of the early thirties slowed things down a bit, but by the

mid-thirties sales were climbing again and Norton became one of the world's leading machines. By 1936 the concern produced no less than 13 models, from 350cc to 633cc. The models all had rigid frames, girder forks and one-cylinder engines.

For general touring at a low initial cost the side-valve models in 500 and 633cc sizes were available; these bikes were particularly popular for sidecar work. For more spirited riding there were six OHV models in 350cc, 500cc and 596cc sizes. These OHV models used the same basic engine design laid down by James Norton in 1913, and this design was retained until 1964 — a tribute to his engineering genius.

A special trials model was also devised with an upswept exhaust pipe, a special frame for more ground clearance, a folding kick starter, wide ratio gearbox, smaller gas tank and narrow fenders. This trials model established a great reputation; on many occasions some members of the victorious British International Six Days Trial team were mounted on Nortons.

The models that really excited the sporting man were the four overhead camshaft machines, two for racing and two for high speed roadwork. The 350cc C.J. and 500cc C.S. 1 models had been introduced in the early thirties, both featuring a single OHC engine which had a cast iron cylinder and head. The cycle parts were built to a "sports" specification for fast touring which, along with the higher cost, meant that these fast roadsters were for the experienced rider.

The 348cc and 490cc International models were intended for racing, although lights were fitted, and either bike was as fine a racing mount as was then available. Bore and stroke dimensions were 71 x 88mm on the 350, and 79 x 100mm on the 500. A large 3-3/4 gallon fuel tank was used and the oil tank was also much larger than standard. The engine could be purchased with an alloy cylinder and head and the carburetor and magneto were of the TT type.

The gearboxes were close ratio, the 500 being 4.4, 4.9, 5.9, and 7.8 to 1. The 350 model had ratios of 5.2, 5.7, 6.8, and 9.2 to 1. A special racing rear seat was included, and the handlebars, seats, footpegs, brakes (7" x 1-1/4"), fenders, and controls were all designed for road racing.

The International was continuously developed; in 1937 it acquired a plunger suspension on the rear end, and in 1947 a hydraulically dampened telescopic fork was used on the front. After the War the C.J. and C.S. 1 models were dropped, the International became the high speed roadster, and the new Manx model became the pukka racer.

During the post-war era the Norton concern produced their first twin, a 500, which has subsequently been developed into a 650 and then recently into a 750cc model. The single cylinder range is now limited to 350 and 500cc pushrod models, and a 250 roadster is included for the lightweight enthusiast. The 500, 650, and 750cc twins may be had in several degrees of tune and specifications, including sports roadsters and a genuine 750cc scrambler with a brutish 60 horsepower. There is also an electric starter model for the sophisticated rider. All have the swinging arm rear suspension system which was introduced in 1953, and the famous Norton Roadholder front fork.

The real story of Norton is not its roadsters though, but rather the history of its racing team. The real pulse-throbbing saga of Norton is racing, so let's go back to 1927 during the golden era of International Grand Prix racing when Walter Moore decided that an overhead camshaft engine was the only answer.

The new engine had a single camshaft which was driven by a vertical shaft between two sets of bevel gears, one set on the mainshaft and one set on the camshaft. The bore and stroke remained at 79 x 100mm, and the engine was mounted in a new cradle frame.

During 1927 and 1928 the OHG engine was used alongside the pushrod model, but the Cammer proved the better of the two. Alec Bennett took the Senior TT in 1927, and Stanley Woods made a record lap at 70.99 mph. Woods also won the Grands Prix of Belgium, Holland and Switzerland, finishing second in the German and third in the Ulster. Bert Denly garnered a whole lot of records that year including the classic hour mark at 100.58 mph, and the 500cc flying kilometer at 109.22 miles per hour.

The successful 500 was joined by a new 350 in 1928, with a bore and stroke of 71 x 81mm. Norton's fortunes declined sharply for a few years then, as a great amount of development work was needed on the camshaft engines, and also because Rudge and Sunbeam were reaping their rewards of years of development on their OHV racers.

Things looked up in 1930 when Arthur Carroll took over the racing department after Walter Moore went to NSU. The exhaust pipe was moved from the left side to the right, the lower bevel gear chamber was redesigned to a box affair and the cylinder and head were improved. Woods won several GPs that year, while the design work went on.

For 1931 the carburetor was down draft slightly; a 14mm spark plug was used, a four-speed gearbox replaced the three-speed version and the semi-slipper type aluminum piston made its appearance. Nortons began their ascendancy of championship racing that year with Stanley Woods and Tim Hunt winning no less than ten GP events, plus Hunt's double in the TT.

In 1932 with the fuel tanks enlarged, the full seven laps of the Isle of Man could be covered with only one refueling stop, and the girder front forks carried a new method of damping, using two small auxiliary springs instead of the usual friction dampers. Nortons really came into their own that year winning seven out of eight of the classic races in the senior class, and five of eight in the junior class.

More improvements were made to the works bikes for 1933; most notable was the adoption of an aluminum alloy cylinder and head. The cylinder had a cast iron sleeve and the head had the alloy fins cast onto a bronze "skull." The team that year consisted of Woods, Hunt, and Jimmy Simpson, who between them won just about everything, with Woods taking the Junior-Senior TT double for the second year in a row.

By 1934 the engines had hairpin valve springs, megaphone exhausts, two spark plugs, twin-spark magnetos, and "bolt through" fuel tanks. The team that year was Walter Rusk, Jimmy Guthrie, Jimmy Simpson and Walter Handley, and they took just about everything except the Senior class Ulster and Swedish GPs.

The 1935 models differed little from the previous year, and Rusk, Guthrie, and J. H. White kept up the winning pace. The only disappointments were in the Senior TT when ex-team member Woods on his Moto Guzzi beat Guthrie by four tiny seconds, and several Junior class events which went to their arch rival, the Velocette. Guthrie capped the year by setting a new one hour record of 114.092 mph at Monthlery.

It was during those years that Grand Prix racing was truly in its golden era, and understandably the Norton was having to face increasingly tougher opposition. Spurred by this, Norton made some major design changes in their 1936 works bikes. A new frame was used which had the plunger type of rear suspension, the remote float chamber was rubber mounted, and the cylinder bore was increased to bring the engine up to 499cc.

A brilliant newcomer named Fred Frith joined White and Guthrie that year. Between them they captured nearly all the Senior races, losing only the Swedish to BMW. In the Junior class they were not quite as successful as in previous years, but the team still was able to win five out of the nine classic events.

The spring of 1937 revealed more design changes on the works bikes, with the most notable being the engine. A new head featuring double overhead camshafts was used, which had a train of five gears to drive the cams from the upper bevel gears. The dual spark plugs were dropped, the finning of the head and cylinder increased, and the valves and springs were still left exposed for cooling.

The Nortons that year proved fast, and Frith, Guthrie and White dominated the TT races with Frith turning his last lap at 90.27 mph. This was the first time the course had been lapped at over the 90 mark. The team fared less well on the continent, picking up only three out of nine Senior class events, but still gaining sufficient points to edge out BMW for the Championship. In the Junior class they finally went under to the Velocette, and Norton was destined not to win this back for fourteen years.

Winner of 34 TTs

Engineering effort then became intense, and for 1938 there were many splendid technical improvements. The most noticeable was the fitting of a telescopic fork at the front which had main and rebound springs but no hydraulic damping. Massive conical wheel hubs were cast from magnesium alloy with ribbed brake drums, and air scoops were provided for cooling.

In an effort to obtain greater rpm and horsepower, the stroke was shortened from 100mm to 94mm on the five hundred, and from 88mm to 77mm on the 350. The bores were opened up from 79 to 82mm, and from 71 to 76mm on the two engines. The finning was again increased on the head and it acquired that square look which was so appealing to the technical minded. Larger bore carburetors were fitted, with the 500 having a 1-5/16 inch venturi. The Senior mount was said to produce 50 bhp at 6,500 rpm for a top speed of 120 to 125 mph. These were truly magnificent racing machines for their day, but then they had to be because their supercharged competition was crowding 150 mph.

For the Senior TT that year Harold Daniell had joined the team. He carried off the trophy at 89.11 mph, and set a 91.0 mph record on his last lap that was destined to stand for 12 years. On the continent the team was faced with rather fearful opposition, as Georg Meier had nearly double the horsepower in his supercharged BMW. The Britishers fought back valiantly, but in the end Meier's speed proved too much. Their only continental victory was in the Swiss GP where better handling paid off on the tortuous corners of the course.

There was little change in the 1939 machines, but Frith's 350 had a bore and stroke of 73.3 x 82.5mm and these dimensions were adopted for the post-war works 350s. Norton failed to win the TT races that year, and on the Grand Prix trail they took a bad drubbing from the blown Gilera and BMW in the Senior class and from the Velocette and supercharged DKW two-stroke in the Junior.

When racing was resumed after the war supercharging was abolished so the Nortons were again back in contention. Pre-war machines were used with small design improvements. In 1948 the front brake was modified to a twin leading shoe assembly and in 1949 the riding position was lowered by using 19" wheels and shortening the front forks.

Despite the antiquity of the bikes, they returned to their winning form of the mid-thirties, and Harold Daniell, Ernie Lyons, Johnny Lockett and Artie Bell were the men to beat in the Senior class racing. Daniell carried off the Senior TT in 1947 and '49, and Bell took the Senior in 1948. Irishman Artie also dominated the 1947 and '48 Grand Prix scenes and won the Championship for Norton. In the Junior class their 350 was not fast enough and they generally had to be content with runnerup positions to the Velocette.

While it is true that Norton won the 1949 Senior TT, the rest of the season was a different story as the AJS "Porcupine," the new Gilera fours and the Guzzi simply outsped them. In fact, in the season's final race over the fast Monza course the team could not even get into the first six places!

It was obvious that the old veteran works bike was obsolete, and so for

1950 an entirely new mount made its appearance. The famous Irish racing brothers, Cromie and Rex McCandless, had been successfully experimenting with a swinging arm frame for their Nortons, and so they were duly invited to help Joe Craig design the new racer.

The swinging arm frame "Featherbed" Norton was born, and so successful was it that it was used on the 1951 production Manx model. The mechanical genius of Joe Craig plus the brilliant riding of newcomer Geoff Duke began to make itself felt, and Norton swept the first three places in the Junior and Senior TT's. On the continent the opposition was a bit tougher. Duke was edged out by Umberto Massetti (Gilera) for Senior Class honors, but the team did manage to win the manufacturer's championship.

By 1951 there was just no stopping Duke, and he won nine out of a possible sixteen races in the Junior and Senior classes. It was in 1952 that more changes were made to the racers with the engine receiving the most attention. Bore and stroke were changed to 75.9 x 77 mm on the 350, and to 85.93 x 86 mm on the 500 with much larger valves and carburetors fitted. These modifications were subsequently adopted on the production Manx, except with measurements of 76 x 76.7mm and 86 x 85.6mm on the two models. Nortons again swept the TT races, but on the continent they had to settle for only the Junior Championship (Duke) as the 500 Gilera was just too fast that year.

In 1953 Geoff Duke left Nortons for Gilera, and a new team comprised of Ray Amm (Southern Rhodesia), Ken Kavanagh (Australia) and Jack Brett (England) carried on the battle. The dogged courage of Amm paid off in both of the TT races, but for the balance of the season the Gilera and Guzzi proved much too fast. The factory did have the satisfaction of a world record though, when Amm used their low streamlined "kneeler" to set a one hour mark of 133.71 mph.

It was obvious that more speed was needed if Norton was to have a chance, so a completely new engine was designed. The 500 and 350 became oversquare with a bore and stroke of 90 x 78.4mm, and 78 x 73mm on the two models. The connecting rod was shortened, and an outside flywheel used. The engine coupled to a new five-speed gearbox, and several types of fairings were used depending on the course.

On these superb racing singles Amm won the Senior TT in appalling weather conditions and also set a Junior lap record of 94.61 mph before retiring. In the Grand Prix chase he put up a courageous battle, taking the Ulster Junior and Senior and the 350cc German GP. It was too much to defeat Gilera and Guzzi in their heyday though, and so Ray was forced to settle for a lesser spot.

Then it was announced in 1955 that Norton was officially withdrawing from genuine works Grand Prix racing. The reason given was that the pukka GP bikes were getting too far removed from production practice, and Norton would concentrate only on their standard Manx model. This was a pity because although Joe Craig was still full of fight, his horizontal single and, yes, even his drawing board four had to be shelved. Truly, an era was ended.

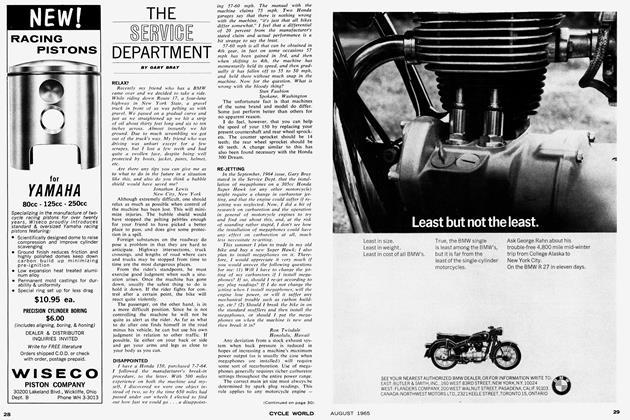

The factory had a team for a few more years which was mounted on the standard 500 and 350cc Manx models with a bore and stroke of 86 x 85.8mm and 76 x 76.85mm. The Manx continued its great reputation as the best production junior and senior mount available, and the marque was even to win two more TTs in 1961 when the lone MV Agustas in each race retired.

In late 1963 it was announced that production of the Manx had ceased, and the factory's only interest in competition was the production machine class where the big 650cc twins have established a fine reputation.

Something has been lost though, and maybe it shall never return. The lusty bellow of the Manx in full flight on the drop down to Creg-ny-Baa, the luster of such names as Woods. Guthrie, Frith, Daniell, Duke, Amm. Mclntyre — this is real history, the kind that just fills the cup full of nostalgia. They say the single is dead, which may or may not be true, but while it lived it was great — the kind of hairy-chested racing machine that will be a legend forever •

View Full Issue

View Full Issue