THE ISLE OF MAN - A Brief History

B. R. NICHOLLS

"THE ISLE OF MAN RACES are unique." How often one reads or hears those words and wonders why a mention of the T.T. in racing circles seems to be treated with reverence. What is the lure? Who is responsible for it all? Why do men and women want to race there? The questions can be endless and many are answerable by guide books and the like. But the purpose of this article is to tell you some of the background to the racing and give some statistics so that the magnitude of the task of organizing these events can be better understood.

It all started way back in 1906 when international racing on the continent of Europe was getting into disrepute and it was suggested that there should be a big road race in England. However, it was impossible to hold it on the mainland. The law, then and now, prohibits closing roads for racing of any kind. So an approach was made to the Manx government who with its more progressive outlook agreed to accommodate the Auto Cycle Club, as it was then known, and allowed them to use a course just over fifteen miles long based on St. Johns in the west of the Island. It embraced half a dozen or so miles of the present course. In that first race there were two classes, single and multi-cylinder machines, and it is fitting that such famous names as Matchless and Norton should have been the winners. Winning speeds of over thirty-six miles an hour on unmetalled roads seemed impossible but were achieved by Charlie Collier and Rem Fowler on the historic occasion. In 1911 the course was changed to the mountain circuit and it brought success to the Indian company of America. Their machines finished first, second and third with the winner averaging over forty-seven miles an hour. Then there was a five-year break for the First World War and by 1922, following minor alterations, the course had fallen into the pattern which is still used today.

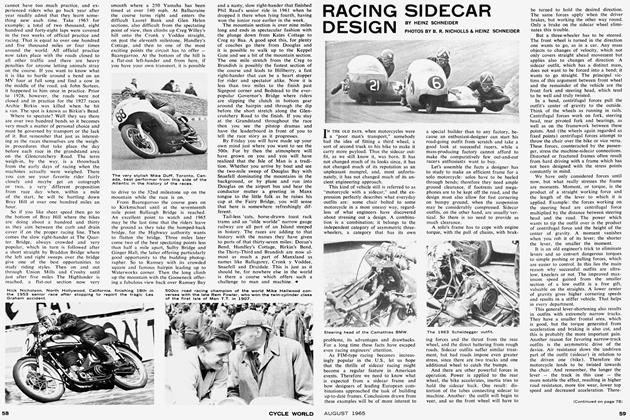

There have been many experiments but the backbone of the races has always been the Senior Tourist Trophy race for 500cc solo machines considered the blue ribbon of road racing and the pinnacle to which all racers aspire. From 1954 to 1959 an alternative circuit known as the Clypse course was used for 125cc and 250cc lightweight and sidecar events. Almost eleven miles in length, it was in places very narrow and therefore most tricky for sidecars Many diehards felt that a Clypse winner should not be referred to as a T.T. winner, such is the tradition of the mountain circuit. But to triple Clypse winner Carlo Ubbiali, the change back to the mountain in 1960 only served to prove his brilliance, for he promptly finished second in the 250 race and won the 125 class. His T.T. record is most impressive: in fifteen races over a period of ten years he retired twice, was fifth once, second seven times and a winner on five occasions.

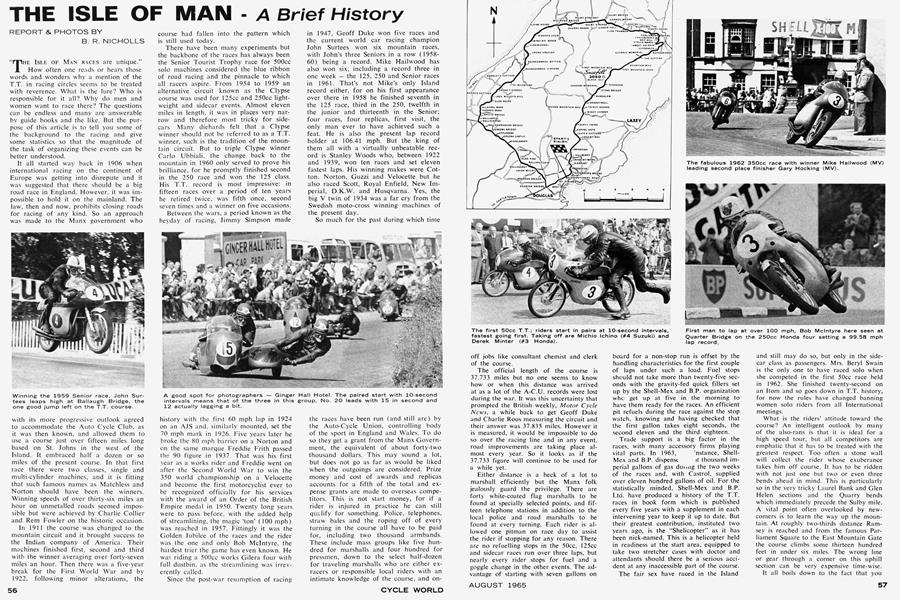

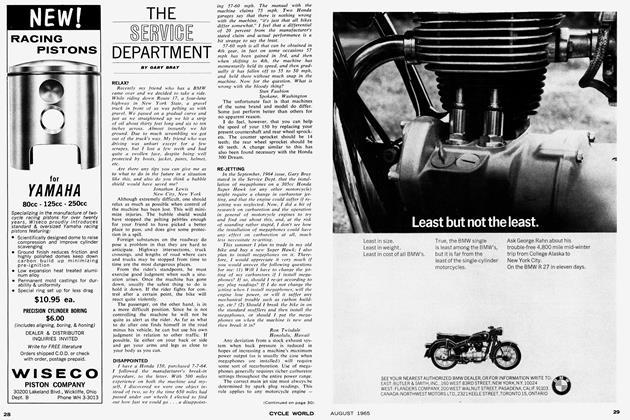

Between the wars, a period known as the heyday of racing, Jimmy Simpson made history with the first 60 mph lap in 1924 on an AJS and, similarly mounted, set the 70 mph mark in 1926. Five years later he broke the 80 mph barrier on a Norton and on the same marque Freddie Frith passed the 90 figure in 1937. That was his first year as a works rider and Freddie went on after the Second World War to win the 350 world championship on a Velocette and become the first motorcyclist ever to be recognized officially for his services with the award of an Order of the British Empire medal in 1950. Twenty long years were to pass before, with the added help of streamlining, the magic 'ton' ( 100 mph) was reached in 1957. Fittingly it was the Golden Jubilee of the races and the rider was the one and only Bob Mclntyre, the hardest trier the game has even known. He was riding a 500cc works Gilera four with full dustbin, as the streamlining was irreverently called.

Since the post-war resumption of racing in 1947, Geoff Duke won five races and the current world car racing champion John Surtees won six mountain races, with John's three Seniors in a row ( 195860) being a record. Mike Hailwood has also won six, including a record three in one week — the 125, 250 and Senior races in 1961. That's not Mike's only Island record either, for on his first appearance over there in 1958 he finished seventh in the 125 race, third in the 250, twelfth in the junior and thirteenth in the Senior; four races, four replicas, first visit, the only man ever to have achieved such a feat. He is also the present lap record holder at 106.41 mph. But the king of them all with a virtually unbeatable record is Stanley Woods who, between 1922 and 1939, won ten races and set eleven fastest laps. His winning makes were Cotton. Norton, Guzzi and Velocette but he also raced Scott, Royal Enfield, New Imperial, D.K.W. and Husqvarna. Yes, the big V twin of 1934 was a far cry from the Swedish moto-cross winning machines of the present day.

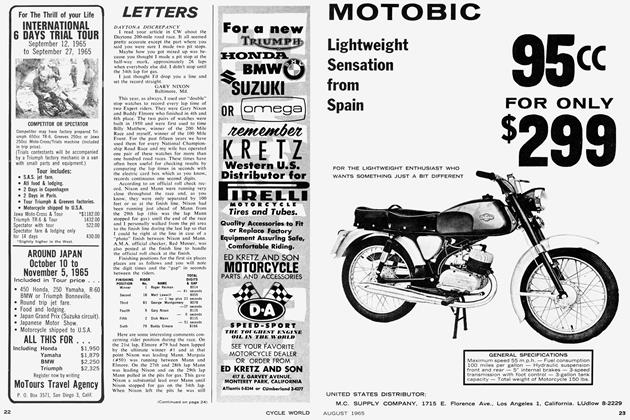

So much for the past during which time the races have been run (and still are) by the Auto-Cycle Union, controlling body of the sport in England and Wales. To do so they get a grant from the Manx Government, the equivalent of about forty-two thousand dollars. This may sound a lot, but does not go as far as would be liked when the outgoings are considered. Prize money and cost of awards and replicas accounts for a fifth of the total and expense grants are made to overseas competitors. This is not start money, for if a rider is injured in practice he can still qualify for something. Police, telephones, straw bales and the roping off of every turning in the course all have to be paid for, including two thousand armbands. These include mass groups like five hundred for marshalls and four hundred for pressmen, down to the select half-dozen for traveling marshalls who are either exracers or responsible local riders with an intimate knowledge of the course, and on-

off jobs like consultant chemist and clerk of the course. The official length of the course is 37.733 miles but no one seems to know how or when this distance was arrived at as a lot of the A-C.U. records were lost during the war. It was this uncertainty that prompted the British weekly, Motor Cycle News, a while back to get Geoff Duke and Charlie Rous measuring the circuit and their answer was 37.835 miles. However it is measured, it would be impossible to do so over the racing line and in any event, road improvements are taking place almost every year. So it looks as if the 37.733 figure will continue to be used for a while yet. Either distance is a heck of a lot to marshall efficiently but the Manx folk jealously guard the privilege. There are forty white-coated flag marshalls to be found at specially selected points, and fifteen telephone stations in addition to the local police and road marshalls to be found at every turning. Each rider is allowed one pitman on race day to assist the rider if stopping for any reason. There are no refuelling stops in the 50cc, 125cc and sidecar races run over three laps, but nearly every rider stops for fuel and a goggle change in the other events. The advantage of starting with seven gallons on board for a non-stop run is offset by the handling characteristics for the first couple of laps under such a load. Fuel stops should not take more than twenty-five seconds with the gravity-fed quick fillers set up by the Shell-Mex and B.P. organization who get up at five in the morning to have them ready for the races. An efficient pit refuels during the race against the stop watch, knowing and having checked that the first gallon takes eight seconds, the second eleven and the third eighteen.

Trade support is a big factor in the races, with many accessory firms playing vital parts. In 1963, :nstance, ShellMex and B.P. dispense it thousand imperial gallons of gas dunng the two weeks of the races and, with Castrol, supplied over eleven hundred gallons of oil. For the statistically minded, Shell-Mex and B.P. Ltd. have produced a history of the T.T. races in book form which is published every five years with a supplement in each intervening year to keep it up to date. But their greatest contribution, instituted two years ago, is the "Shelicopter" as it has been nick-named. This is a helicopter held in readiness at the start area, equipped to take two stretcher cases with doctor and attendants should there be a serious accident at any inaccessible part of the course. The fair sex have raced in the Island and still may do so, but only in the sidecar class as passengers. Mrs. Beryl Swain is the only one to have raced solo when she competed in the first 50cc race held in 1962. She finished twenty-second on an Itom and so goes down in T.T. history, for now the rules have changed banning women solo riders from all International meetings.

What is the riders' attitude toward the course? An intelligent outlook by many of the also-rans is that it is ideal for a high speed tour, but all competitors are emphatic that it has to be treated with the greatest respect. Too often a stone wall will collect the rider whose exuberance takes him off course. It has to be ridden with not just one but two or even three bends ahead in mind. This is particularly so in the very tricky Laurel Bank and Glen Helen sections and the Quarry bends which immediately precede the Sulby mile. A vital point often overlooked by newcomers is to learn the way up the mountain. At roughly two-thirds distance Ramsey is reached and from the famous Parliament Square to the East Mountain Gate the course climbs some thirteen hundred feet in under six miles. The wrong line or gear through a corner on this uphill section can be very expensive time-wise.

It all boils down to the fact that you cannot have too much practice, and experienced riders who go back year after year readily admit that they learn something new each time. Take 1963 for example; a total of two thousand, eight hundred and forty-eight laps were covered in the two weeks of official practice and racing. That is equal to over one hundred and five thousand miles or four times around the world. All official practice now takes place with the roads closed to all other traffic and there are heavy penalties for anyone letting animals stray on the course. If you want to know what it is like to hurtle around a bend on an MV four at full song and find a cow in the middle of the road, ask John Surtees, it happened to him once in practice. Prior to 1928, however, the roads were not closed and in practice for the 1927 races Archie Birkin was killed when he hit a van. The spot is known as Birkin's Bend.

Where to spectate? Well they say there are over two hundred bends so it becomes very much a matter of personal choice and must be governed by transport or the lack of it. But remember that just as interesting as the races themselves are the weighin procedures that take place the day before each race in the grandstand area on the Glencrutchery Road. The term weigh-in, by the way, is a throwback from the early days of racing when the machines actually were weighed. There you can see your favorite rider fairly closely and maybe get an autograph or two, a very ' different proposition from race day when, within a mile of the start, he will be hurtling down Bray Hill at over one hundred miles an hour.

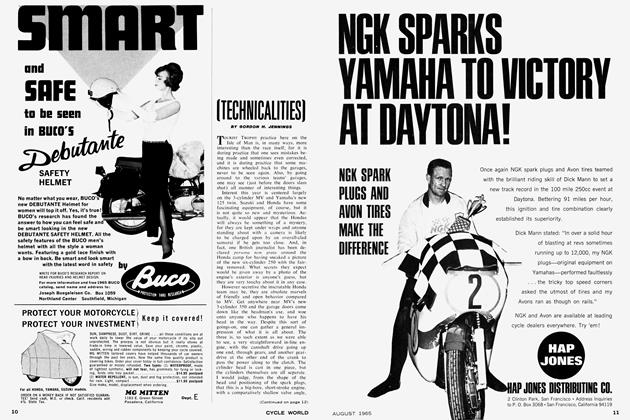

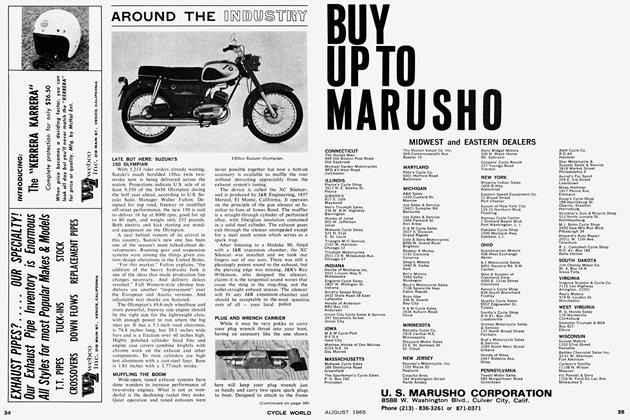

So if you like sheer speed then go to the bottom of Bray Hill where the bikes are doing about a hundred and thirty as they aim between the curb and drain cover if on the proper racing line. Then comes the slow right-hander at The Quarter Bridge, always crowded and very popular, which in turn is followed after a short straight by Braddan Bridge where the left and right sweeps over the bridge give one of the best opportunities to study riding styles. Then on and out through Union Mills and Crosby until just after five miles The Highlander is reached, a flat-out section now very smooth where a 250 Yamaha has been timed at over 140 mph. At Ballacraine the course turns right and enters the difficult Laurel Bank and Glen Helen sections, also difficult from the spectating point of view, then climbs up Creg Willey's hill onto the Cronk y Voddee straight, on past the eleventh milestone, Handley's Cottage, and then to one of the most exciting points the circuit has to offer — Baaregarroo. At the bottom of the hill is a flat-out left-hander and from here, if you have your own transport, it is possible

to drive to the 32nd milestone up on the mountain while the race is on. From Baaregarroo the course goes on to Kirkmichael until at the seventeenth mile point Ballaugh Bridge is reached. An excellent point to watch and 1965 may be the last time that the riders leave the ground as they take the humped-back bridge, for the Highway authority wants to flatten the bridge. Three miles later come two of the best spectating points less than half a mile apart, Sulby Bridge and Ginger Hall, the latter offering particularly good opportunity to the budding photographer. So to Ramsey with its crowded square and famous hairpin leading up to Waterworks corner. Then the long climb up the mountain with the Gooseneck offering a fabulous view back over Ramsey Bay and a nasty, slow right-hander that finished Phil Read's senior ride in 1961 when he dropped it there when lying fourth, having won the junior race earlier in the week.

The mountain section is over nine miles long and ends in spectacular fashion with the plunge down from Kates Cottage to Creg ny Baa. A good spot this, for plenty of coaches go there from Douglas and it is possible to walk up to the Keppel Gate and see a bit of the mountain section. The one mile stretch from the Creg to Brandish is possibly the fastest section of the course and leads to Hillberry, a fast right-hander that can be a heart stopper for rider and spectator alike. Now it is less than two miles to the finish past Signpost corner and Bedstead to the everpopular Governor's Bridge where riders are slipping the clutch in bottom gear around the hairpin and through the dip before the short stretch along the Glencrutchery Road to the finish. If you stay at the Grandstand throughout the race then you see the pitstop dramas and have the leaderboard in front of you to tell the race story as it progresses.

By Friday you will have made up your own mind just where you want to see the 500s. For by then the atmosphere will have grown on you and you will have realized that the Isle of Man is a tradition. Whether you arrive by boat and see the two-mile sweep of Douglas Bay with Snaefell dominating the mountains in the background, or by plane and run into Douglas on the airport bus and hear the conductor mutter a greeting in Manx tongue to the little folk as he raises his cap at the Fairy Bridge, you will sense that here is somewhere refreshingly different.

Tail-less 'cats, horse-drawn toast rack trams and an "olde worlde" narrow gauge railway are all part of an Island steeped in history. The races are adding to that history with the names they have given to parts of that thirty-seven miles: Doran's Bend, Handley's Cottage, Birkin's Bend, the Thirty-Third and Brandish are now almost as much a part of Manxland as names like Ballagarey, Cronk y Voddee, Snaefell and Druidale. This is just as it should be, for nowhere else in the world is there a course which offers such a challenge to man and machine. •

View Full Issue

View Full Issue