HONDA HISTORY

HONDA

IN ALL THE ANNALS of motorcycledom, a unique story standing apart from all the others is that of Soichiro Honda, the world’s largest producer of motorcycles. It is a rags to riches legend that is second to none.

Born in 1906 in Hamamatsu, Japan, Soichiro grew up in a small village atmosphere where his father was a blacksmith. With a confessed interest in engines at the early age of five years, Soichiro recalls that when he was in the second grade of schooling, the first automobile came to their town. It leaked some oil on the ground when it stopped, and Honda remembers that he literally put his nose to the ground and deeply breathed in the aroma. From that day, Soichiro Honda has been breathing engine oil.

With a notable lack of interest in his studies (reading and writing in particular), young Honda left school at 16 to become an auto mechanic apprentice with the Art Trading Company. This business was one of the few repair shops in Tokyo, as cars were still very scarce in Japan. After a period of time in which he did domestic work for his employer rather than learning the mechanic trade, Soichiro Honda finally began his serious studies of the automobile.

Then, only 18 months after he went to work, the city was leveled by the terrible earthquake of 1923, and in the resulting fire, both the city and his master's business were burned to the ground. Following the holocaust, Honda's employer retained his services to repair the many burned automobiles. It was then that Soichiro first came in contact with a motorcycle, as he ran errands about town with a sidecar rig.

By age 22 he had become a mechanic of some renown, and so he returned to his home town to set up his own repair shop. Business was slow at first, because there were already two repair shops in Hamamatsu. But Soichiro's ability to get the tough jobs running soon manifested itself and his clientele expanded.

It was also in those early days that young Honda got his first taste of racing, when he built up a racing car for his old employer. Soichiro first tried a Daimler-Benz six cylinder engine, but later switched to a 90 hp Curtis airplane engine. Mounted in an old car frame, the primitive racing car proved fast, clocking 100 kph (68 mph) at a Tokyo airfield.

Soichiro then decided to build some racing cars at Hamamatsu, and he later raced them with a fair amount of success. At age 31, however, his automobile racing days came to a screeching halt, when his supercharged Ford four-cylinder job somersaulted three times, end over end. The event was the All-Japan Automobile Speed Championships and, even though he was given the trophy for the new speed record, his injuries halted any future speed studies.

After leaving the hospital, an indomitable spirit moved Honda to try his hand at manufacturing piston rings. In this venture. Soichiro found his product somewhat lacking in quality and, in fact, they were so bad he could not even sell them. With 50 employees on the payroll, he was destitute; he even pawned his wife’s wardrobe to get the money to attend a metal casting school.

Just nine months later, the piston rings he produced were among the finest in Japan, and the little company prospered. During World War II the concern produced piston rings for the Japanese military effort, and after the war the business was sold.

Soichiro then spent some time trying to make salt out of sea water, and later manufactured a rotary type weaving machine. These efforts proved fruitless. So in 1948 the Honda Technical Research Institute was founded in Hamamatsu. The original plant was a truly breathtaking industrial spectacle — a 12by 18-foot wood frame shack, one rickety beltdriven lathe, a dilapidated machine tool, a couple of desks, and 12 hungry men.

GEOFFREY WOOD

In the completely disrupted society of the immediate post-war years, one of the most pressing Japanese domestic problems was that of transportation. The country was desperately poor, and the masses were forced to crowd into the archaic trains, buses and taxis to get to their jobs. In this atmosphere, Honda correctly decided that a motorized bicycle was just the ticket for cheap and speedy transportation.

The first product featured a small twocycle engine that the Imperial army had used to power communications equipment, and these little lungers were mounted on a bicycle. The production was only one unit per day. and the engines ran on a fuel extracted from the roots of pine trees. These primitive motorbikes sold like hotcakes in transportationstarved Japan, and the supply of 500 engines was soon exhausted.

This lack of engines called the hand of the aspiring industrialist, and he responded to the challenge by designing a one-half horsepower 50cc two-stroke engine. When initial tests were completed, the new powerplant was refined and then put into production. The motorized bicycle met with tremendous public acceptance, and production came nowhere near to satisfying demand. With this modest but burgeoning foundation, the Honda Motor Company was incorporated in 1948 with 34 employees and $2,777 capital.

This event proved to be a great milestone in the industrialization of Japan, as the country has economically lagged well behind Europe and America for the greater part of this century. Just consider, for instance, that in 1940 only 3,000 motorcycles were produced, and in 1945 it had declined to the meager sum of only 127 machines per year. Even in 1947 there were only 446 bikes turned out by Japanese manufacturers, and this production rate increased to only 1,394 by 1950.

When Honda Motor Company was organized in 1948, there were only eight motorcycle manufacturers in Japan. However, none of these companies made both their own frames and engines, and this complete motorcycle production goal was one of Soichiro's dreams. In August of 1949, his dream came true when the lOOcc D model rolled off the assembly lines. The new D model featured a 2.3 hp twostroke engine which drove through a twospeed gearbox and chain drive. The frame was a pressed steel type and it had no method of rear suspension. The front end had a clean looking telescopic fork.

The new Honda was called the “Dream” by the company since it fulfilled the maker’s dream of the first complete Japanese motorcycle. The D model was well ahead of Japanese competition too, but its introduction happened at the wrong time, as the country was hard hit by an economic depression. Sales dropped, collections were slow, and the company was on the verge of bankruptcy.

By now, Soichiro had come to realize that while he was an engineer and technician par excellence, he was not a financier or salesman. He decided then, and wisely so, to hire Takeo Fujisawa as sales and financial director. With this new management team, the company pulled through the crisis and established itself as a small, but sound Japanese industry.

In 1950, the company expanded by opening a new office in Tokyo and Honda was able to obtain a $5,555 loan from the Japanese government to purchase new machinery. Production and sales increased, and soon 300 Dream models were rolling off the assembly lines each month. This was a truly remarkable feat, as all the other Japanese manufacturers together were producing only about 1,600 machines per year.

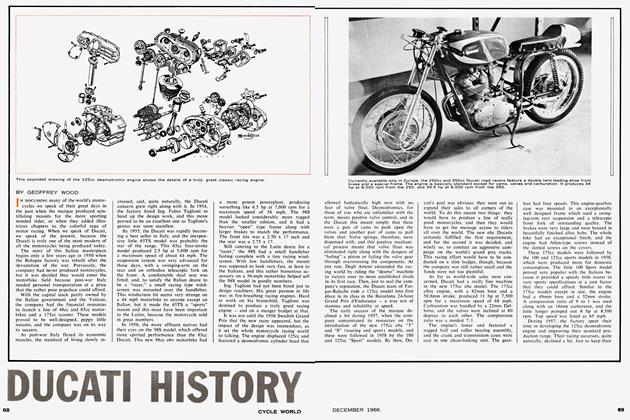

During the early 1950s, Japan began a rapid industrial growth, and Honda grew right along with it. With the standard of living in a sharp rise, Soichiro decided that the luxury of a four-cycle engine could be afforded by the populace, and so the 150cc E model made its debut. The initial testing of the E model was a tense moment at the factory though; on the day of the test a typhoon raged over Japan. The factory test rider rode the new 150 to the top of Hakone Mountain and back in a driving rain. The rider’s evaluation was that Honda had a real winner in the E model, and into production it went.

The E model featured a 5.5 bhp engine mounted in a pressed-steel frame as had its predecessor, the D model. Still rather primitive and looking like a mid-1935 German motorcycle, the E model nevertheless was a sensation in Japan. With a top speed of 50 mph, the new Honda sold to the tune of 32,000 in 1953 — an unheard of figure in the Japanese industry. With the mushrooming sales, the company continued to expand, and capital was listed at $166,000, sixty times what the concern was worth only five years earlier.

In May of 1952. the company again returned to the motorized bicycle field with the introduction of the 50cc Cub unit. The public response to the little onehalf horsepower two-stroke was tremendous, and production was soon up to 6,500 units per month. This Cub model, which was designed by Soichiro, himself, garnered more than seventy per cent of the domestic “clip-on’’ market, and this feat earned him the coveted Blue Ribbon Medal by the Emperor.

By then a greater percentage of the company’s profits was being plowed back into research, while a succession of great models began emerging from the designer's desk. In June of 1953, the 90cc fourstroke Benly came off the line, and this model found an immediate acceptance by the motorcycling public. The new Benly produced a healthy 3.8 hp and it had a three-speed footshift gearbox. The frame was an entirely new pressed sheet-steel type, with a telescopic front fork and a type of torsion arm rear suspension. The Benly was a much more modern looking Honda than previous models, and production was soon up to 1,000 per month.

By this time. Honda had reached the limit with his archaic machinery, as nearly all of his factory equipment was either pre-war or domestically produced. The engineering ability of his technical department exceeded the production capabilities of l)is machinery. Additionally, Soichiro had ideas of worldwide marketing of his Hondas, but his plant was incapable of producing a machine that could successfully compete in the world market.

Soichiro announced that $1,111,000 worth of American, German, and Swiss machine tools were being purchased to make his factory one of the most modern in the world. The timing of this expansion was once again a critical factor in the history of the company, as Japan again experienced an economic recession in 1953 and 1954. After some anxious financial moments, managing director Fujisawa brought the company through to quieter waters and the expensive new machinery began paying its way.

With the company pnce again doing well and his confidence restored, Soichiro announced in March of 1954 that Honda would soon enter the very pinnacle of motorcycle racing, the famed Isle of Man TT races. Honda's reasoning was most logical; in order to expand sales worldwide. it would be necessary to successfully compete against Europe's best to demonstrate the superiority of the Honda. With this in mind, the company president made a trip to the Isle of Man to gain some experience for their upcoming venture.

So off to the 1954 TT races he went, full of confidence that his machines, which were used in Japanese racing, could be competitive to the best that Europe produced. Two weeks later, Soichiro returned home, half in shock and half in despair. He had found the European racing bikes developing three times the best power he could raise, and the overall technical superiority of their bikes was devastating to his confidence. All he promised was that he would be back; when, he didn’t know, but he would return.

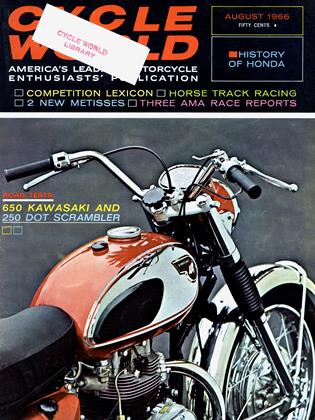

Back in Japan, he turned his efforts toward improving his range of machines, and in 1955 several new models made their appearance. One, the SA model, was a clean looking OHV 250 with a swinging arm rear suspension. With the standard of living constantly increasing, the home country populace could afford more comfort, more performance, and more luxury.

The program continued to expand in 1958, with another great milestone in the company’s history — the 50cc Super Cub. This new Honda was not designed for

the motorcyclist, but rather for the

“everyman-on-the-street.’’ An enclosed engine and step-through frame made this

the most popular of Hondas, with moms, dads, and kids, all in on the fun.

This was followed in 1959 by the expansion of Honda throughout the world, including the United States, and the subsequent introduction of the overhead camshaft twins. Since then, Honda sales charts go in a nearly vertical direction

and today, they are the undisputed sales leaders in the world.

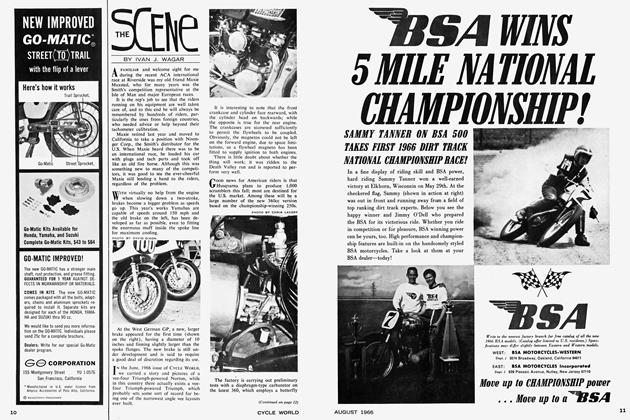

The highlight of the range is, no doubt, the recently introduced 444cc double overhead camshaft model. Designed to satisfy the most discriminating buyer of a motorcycle, the new double knocker model develops 43 hp at 8,500 rpm for a top speed of more than 100 mph. With the first double overhead cam engine ever featured in a road bike, the new Honda sets a trend in performance, combined with such luxury touring features as an electric starter.

In the whole story of Honda, the reallv great rise of the company occurred when their racing bikes began winning on the classical grand prix road racing courses of the world. After Soichiro visited the Isle of Man in 1954, the company contented itself with winning their homeland races until 1959, when they returned to the TT races with a team of 125cc twins. The little DOHC Hondas produced a claimed 18.5 hp at 14,000 rpm, and the camshaft drive was by bevel gear and vertical shaft. The front fork was a cumbersome looking leading link affair, and the total weight was 176 pounds.

The race results netted the little twins sixth, seventh, eighth, and eleventh places, which were good enough to win them the team prize, as no other team finished intact. Their speed seemed to suggest that the horsepower claim was a bit exaggerated, and the handling was described as being “plain terrible." Obviously, Honda had a lot to learn.

Back to Japan they went, and the 125cc twin was joined by a 250cc four-cylinder model for the national Asama Championship race. Hondas made a clean sweep of the two classes, before being recalled to the design shop for a winter’s work.

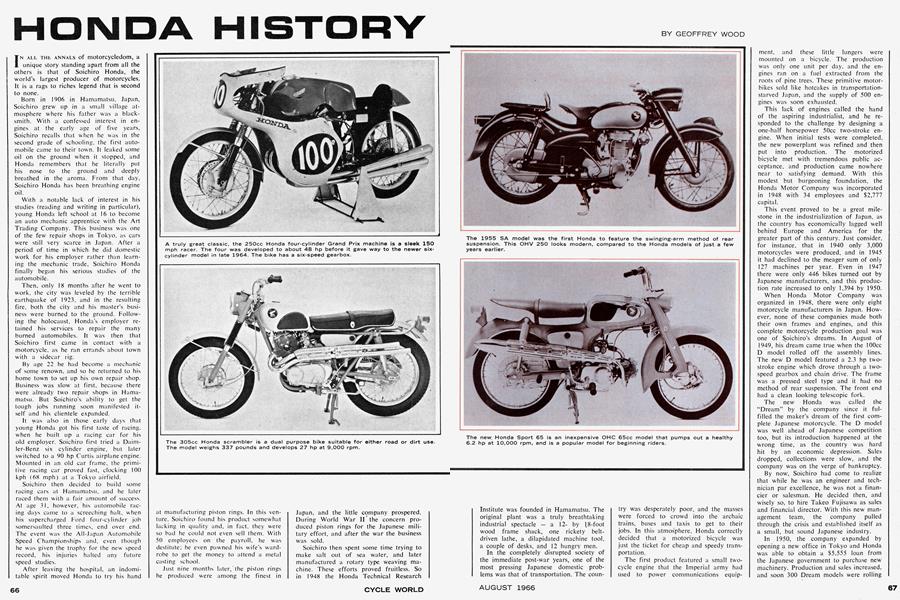

In 1960, Honda returned to Europe with the new 125cc-twin and 250cc-four cylinder racers. Gone was the old frame and fork; in its place a more orthodox frame with a telescopic fork. The engines were canted forward in the frame to give better cooling, and the camshaft drive was changed to a set of spur gears. Another innovation was the four valves per cylinder arrangement, an idea copied from their earlier experimental 125cc twin.

(Continued on page 88)

The handling of the new racers was notably improved, and horsepower was obviously greater. Ridden by both Japanese and experienced European grand prix riders, the team put up a respectable showing. In the TT, a 250 took sixth place, and the 125 class had Hondas in fourth, fifth, and sixth places.

In the Dutch GP, a sixth was obtained in the 125 class. Then followed the fast Belgian event and Honda drew a blank. Next was the German event and the 250four garnered a third and a sixth place. Honda followed this up with a second and fifth in the Ulster GP. The last event of the season at Monza had 250 models in second, fourth, fifth and sixth places, as well as fourth and sixth in the 125cc class. Altogether it was a good year, but still down on speed from the European machines.

Another winter’s work yielded more horsepower plus a general refinement of the two models. The little twin was by then developing 25 hp at 13,000 rpm for a top speed of about 112 mph. The 250 four was rated at 45 hp @ 14,000 rpm for a maximum speed of 137 mph. Both models featured six-speed gearboxes and had the four valves per cylinder arrangement.

Soichiro, always a quick one to recognize talent, had come to the conclusion that his Japanese riders were just not good enough to successfully compete against the more experienced grand prix riders. By hiring such aces as Jim Redman, Southern Rhodesia, Tom Phillis, Australia, Luigi Taveri, Switzerland, and Mike Hailwood, England, to head up the racing effort, Honda had a truly formidable team. In addition, the great Bob McIntyre was engaged just before the Isle of Man classic.

In the opening race of the season, Tom Phillis notched Honda’s first grand prix win when he garnered the 125cc event in Spain. Gaining momentum, the team swept on to the TT races, where Hailwood took both the 125 and 250 events, and in the latter race McIntyre put in his incredible 99.58 mph lap from a standing start. By the end of the season, it was Hailwood with the 250cc World Championship and Phillis wearing the 125 crown.

During 1962, the Hondas continued their domination of lightweight class racing, with a new 50cc-single added to the range for the just recently included 50cc class. Hailwood quit the team and went over to MV Agusta, and Irishman Tommy Robb joined the team. Hondas swept the board in the 125 and 250 classes, but in the 50cc class, their little single was getting slaughtered by the Kreidler and Suzuki two strokes.

Luigi Taveri, their popular little Swiss rider, took the 125cc Championship, and Redman won the 250 crown. A big surprise was Redman also winning the 350cc class on a 250 model bored out to 285cc. Altogether a truly great year.

For 1963, Honda’s interest in racing seemed to sag a bit, and Redman proved to be their only rider winning a championship. Jim easily won the 350 crown, but in the 250cc class he had to win the final event in Japan to defeat Tarquinio Provini and his embarrassingly fast Morini-single. The season’s score was only 15 classic wins, and six of these were in the “competitionless” 350 class.

For 1964, Honda made a determined effort with a new 50cc-twin and a 125four, both turning to something like 19,000 to 20,000 rpm. Horsepower on the 250-four was up to 48 for a speed of about 150, and the 56 hp 350 was capable of around 156 mph.

The new 50cc twin proved very fast, but Suzuki retained their title by winning the last event of the season in Finland. On the remarkably fast 125, Taveri squashed the two-stroke opposition, and Redman had a walkover in the 350 class. In the prestigious 250 class, the 250-four was beaten back by the speedier Yamaha two-stroke twin. Honda, obviously, could not endure such humiliation, and so late in the season a new 250 six-cylinder model made its debut.

Once again making a determined effort in 1965, Honda unveiled the very ultimate in GP equipment. The 50 remained a twin, the 250 a six, and the 350 a four, but the new 125 had the rather unusual number of five cylinders and with revs up to 22,000. The 1965 Hondas all proved to be very fast, and they certainly represent the ultimate in four-stroke engine technology. In the Isle of Man, for instance, riders were timed through a two-mile section that has several curves and swerves. The little 50cc twin rocketed through at 109 mph, Jim Redman’s 350 clocked 133 mph, and even the 125s averaged 122 mph.

After several years of trying, the little 50cc twin finally won the championship in the hands of Irishman Ralph Bryans, and Redman once again took the 350 crown, after a torrid battle with Giacomo Agostini on the MV Agusta “three.” In the 250 class the Yamaha still held the edge, as did Suzuki in the 125 class.

With obvious intentions of gaining back some of their lost prestige, Honda announced, late in 1965, that Mike Hailwood would ride for them during the 1966 season. By adding what is generally considered to be the finest rider in the world to their team, Honda is serving notice on the racing world that they are going to make a determined effort to gain the championships. Having been promised a 500cc model, Hailwood’s entrance into the senior class should really make the sparks fly.

The real goal of Honda, however, has been to offer a range of motorcycles for the everyday rider. From 50cc transportation mounts to the super-sporting double knocker 450 — there is a Honda for everyone. Surely, Soichiro Honda must go down in history with such names as Daimler-Benz and Henry Ford as being a truly great milestone in the transportation era.