THE SCENE

IVAN J. WAGAR

A FAMILIAR and welcome sight for me during the recent ACA international race at Riverside was my old friend Maxie Maxsted, who for many years was the Smith’s competition representative at the Isle of Man and major European races.

It is the rep’s job to see that the riders running on his equipment are well taken care of, and to this end he will always be remembered by hundreds of riders, particularly the ones from foreign countries, who needed advice or help beyond their tachometer calibration.

Maxie retired last year and moved to California to take a position with N ¡songer Corp., the Smith’s distributor for the U.S. When Maxie heard there was to be an international race, he loaded his car with plugs and tach parts and took off like an old fire horse. Although this was something new to many of the competitors, it was good to see the ever-cheerful Maxie still lending a hand to the riders, regardless of the problem.

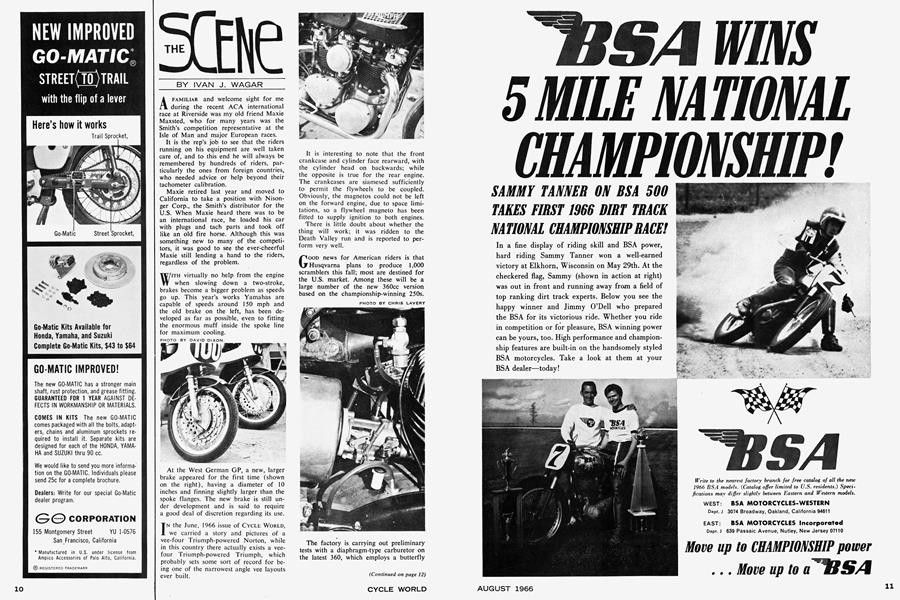

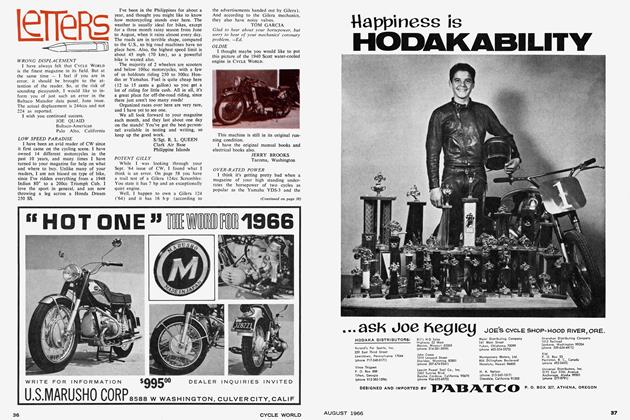

WITH virtually no help from the engine when slowing down a two-stroke, brakes become a bigger problem as speeds go up. This year’s works Yamahas are capable of speeds around 150 mph and the old brake on the left, has been developed as far as possible, even to fitting the enormous muff inside the spoke line

for maximum cooling.

At the West German GP, a new, larger brake appeared for the first time (shown on the right), having a diameter of 10 inches and finning slightly larger than the spoke flanges. The new brake is still under development and is said to require a good deal of discretion regarding its use.

IN the June, 1966 issue of CYCLE WORLD, we carried a story and pictures of a vee-four Triumph-powered Norton, while in this country there actually exists a veefour Triumph-powered Triumph, which probably sets some sort of record for being one of the narrowest angle vee layouts ever built.

It is interesting to note that the front crankcase and cylinder face rearward, with the cylinder head on backwards; while the opposite is true for the rear engine. The crankcases are siamesed sufficiently to permit the flywheels to be coupled. Obviously, the magnetos could not be left on the forward engine, due to space limitations, so a flywheel magneto has been fitted to supply ignition to both engines.

There is little doubt about whether the thing will work; it was ridden to the Death Valley run and is reported to perform very well.

GOOD news for American riders is that Husqvarna plans to produce 1,000 scramblers this fall; most are destined for the U.S. market. Among these will be a large number of the new 360cc version based on the championship-winning 250s.

The factory is carrying out preliminary tests with a diaphragm-type carburetor on the latest 360, which employs a butterfly and emulsion jets, rather than the float chamber and needle controlled mixture jets usually found on motorcycles. Externally adjusted screws can be set during tuning to give correct mixture, while an accelerator pump, controlled by the butterfly shaft, permits rapid throttle response.

(Continued on page 12)

Although the new carb seems to work quite well, it will not be fitted to the series production models if trouble is encountered. Main advantage with a carburetor of this type is that a large choke diameter can be used without the carb body hitting the top of the crankcase, always a problem with high performance two-strokes, where the inlet port is mounted low in the cylinder.

FTRST photo of the new full double loop Honda frame to reach the U.S. shows the lower members actually bolted into place. While this may seem peculiar in this day of all-welded frames, it is in this case necessary to do it this way; the very low sump on the racing engines would mean extremely low bottom tubes if the engine is to be put in or taken out. A second disadvantage would be long engine plates in order to reach the existing mounting holes.

This has come about as a result of Mike Hailwood’s frank evaluation of the handling last year when he said it was “bloody awful,” and, although it may not be as strong as an all-welded frame, it does get the job done. Even Phil Read admits that last year it was fairly easy when Jim Redman was all alone and the Honda handled badly, but now with Jim and Mike on them, plus the improved handling and without the aid of Duff to back him, the season ahead looks pretty grim. One thing is certain; if the Honda company continues the way it has been going so far this year, they won’t have to compete in the Japanese GP on “the other” course, and that is their goal.

THE sidecar boys are faced with the same problems as the solo runners who try to compete against MVs, Hondas or Yamahas. In sidecar racing, the heavy opposition comes from one or two people having the very precious short-stroke dohc factory BMW engines; the more common longstroke unit is simply no match. And, as a result, some very unusual powerplants turn up among the charioteers.

Latest recruit in the “new” brigade is 1960 sidecar world champion Helmut Fath. Helmut has a good reputation already, having been the brains behind the FCS (Fath-Camathias Special), now owned by Colin Seeley, and which was developed for Florian to wax Deubel, who had a factory engine.

Since his terrible crash at Nurburgring, where he lost a leg and his passenger was killed, Helmut has kept busy building a house completely by himself, in addition to a new sidecar outfit, including engine. The sidecar is interesting, because it is the only one in Grand Prix racing with telescoping front forks; everyone else uses a form of leading link to keep height to a minimum. Helmut has been able to keep his outfit low by mounting the wheel spindle five inches from the bottom of the homemade forks.

The engine, besides being homemade, is unique in several respects. It has fuel injection, favored by Fath on the FCS, the fuel being fed by a positive pump directly to the intake port. Air is controlled by a long, flat slide with four port holes and moving horizontally across the intake ports. At full throttle, all of the ports are lined up, at which point the injector pump,,driven by an auxiliary pinion from the cam drive gears, is on maximum delivery.

All engine castings are aluminum, except for magnesium cambox covers. The cylinders feature hard chrome bores and have super over-square dimensions of 62 x 41 mm; this is a bore/stroke ratio of 3:2! With a compression ratio of 10:1, the engine has good power from 11,000 to 13,000 rpm and 14,000 can be used for short periods.

Titanium connecting rods are used on a five mainbearing crankshaft, which has the cranks set at a 90 degree angle, rather than the usual 180 degrees generally found on four-cylinder engines. A flywheel is used between cylinders one and two, and another flywheel between numbers three and four.

Although there have been some minor problems, the engine appears to be reliable and looks like it could be a real threat by the end of the season.