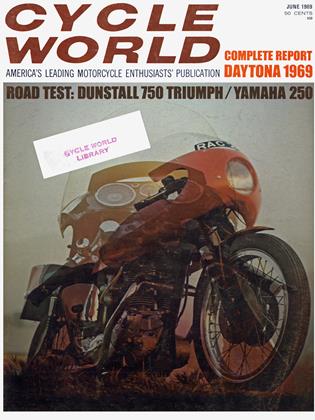

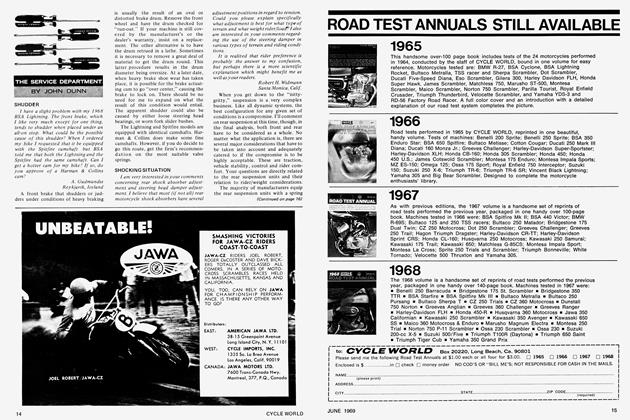

DAYTONA1969

What Do These People Have In Common?

They All Endured...Enjoyed (pick one or both)

IVAN J. WAGAR

DAN HUNT

AH, DAYTONA. Sleepy Florida coast town of dank motels, little old retired ladies, corny music and slow service—an odd setting for America’s biggest motorcycle road race.

But it is the closest thing to the Isle of Man that we can muster, and there are even a few similarities. Nearby water, the week-long buildup to a climactic three days of racing, droves of colorful (or off-color) bikeys patrolling the streets, and the massive attendance of trade and press, all politicking it up in a clammy deluge of alcohol and mediocre food. There is revelry for all. But it must be looked upon as a nightmare of endurance by those who are there to conduct business. Even the Daytona branches of Hertz and Avis regard the festivities with terror. They know they’ll have to write off several of their cars, either as wrecks or floating corpses. One racer is alleged to have “used up” four of them during his stay. Another, who was frolicking with his rent-a-car near the old beach race course, had to leave the cockpit hastily when the water got too deep. For those who survived the wrath of Avis, the Medusean hordes, the dull trade show, the nightly short track races (Expert Mark Brelsford didn’t), and a week-long delay for the big-bore feature, the races were ample reward. This may have been the greatest Daytona yet, for competition was extremely close in all classes.

The entry was more international than ever before. Two-wheeled drifting, fairing to fairing, in the fast infield turns was the rule. The over-150-mph speeds on the banking are awesome. The quality of AMA road racing has improved markedly in the past few years, and foot dropping and wide bars are a thing of the past. A rider who doesn’t make at least a superficial attempt to ride European style is now the butt of laughter.

The improvement is not a sui generis renaissance within the circle of AMA professionals. It is the result of crosspollination. The AMA inner circle may never idolize European grand prix champions, but it surely listens to what they have to say about the craft. The top placings reveal not a preponderance of hard-core damn-the-outlaws AMA heroes, but a significant share of riders who learned the art of vitesse in FIMaffiliated groups. This is not to say that AMA road racing has not been exciting in the past. It has always been a hairy spectacle, in the brave do-or-die tradition of Roman gladiator sport. But, this year, baby, you couldn’t just gas it. You had to have class, too.

200-MILE EXPERT

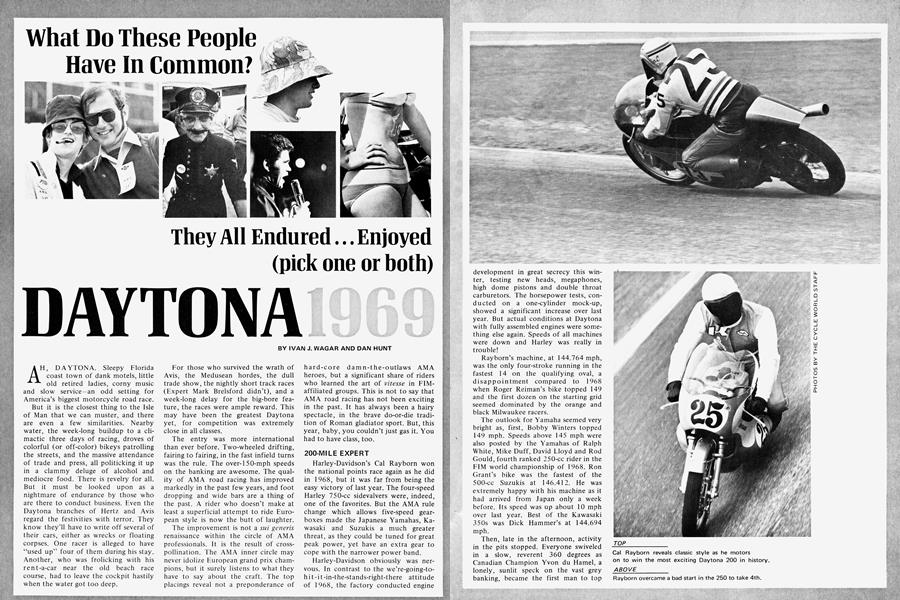

Harley-Davidson’s Cal Rayborn won the national points race again as he did in 1968, but it was far from being the easy victory of last year. The four-speed Harley 750-cc sidevalvers were, indeed, one of the favorites. But the AMA rule change which allows five-speed gearboxes made the Japanese Yamahas, Kawasaki and Suzukis a much greater threat, as they could be tuned for great peak power, yet have an extra gear to cope with the narrower power band.

Harley-Davidson obviously was nervous. In contrast to the we’re-going-tohit-it-in-the-stands-right-there attitude of 1968, the factory conducted engine development in great secrecy this win ter, testing new heads, megaphones, high dome pistons and double throat carburetors. The horsepower tests, con ducted on a one-cylinder mock-up, showed a significant increase over last year. But actual conditions at Daytona with fully assembled engines were some thing else again. Speeds of all machines were down and Harley was really in trouble!

Rayborn's machine, at 144.764 mph, was the only four-stroke running in the fastest 14 on the qualifying oval, a disappointment compared to 1968 when Roger Reiman's bike topped 149 and the first dozen on the starting grid seemed dominated by the orange and black Milwaukee racers.

The outlook for Yamaha seemed very bright as, first, Bobby Winters topped 149 mph. Speeds above 145 mph were also posted by the Yamahas of Ralph White, Mike Duff, David Lloyd and Rod Gould, fourth ranked 250-cc rider in the FIM world championship of 1968. Ron Grant's bike was the fastest of the 500-cc Suzukis at 146.412. He was extremely happy with his machine as it had arrived from Japan only a week before. Its speed was up about 10 mph over last year. Best of the Kawasaki 350s was Dick Hammer's at 144.694 mph.

Then, late in the afternoon, activity in the pits stopped. Everyone swiveled in a slow, reverent 360 degrees as Canadian Champion Yvon du Hamel, a lonely, sunlit speck on the vast grey banking, became the first man to top 150 mph (150.501) in qualifying. His 350-cc Yamaha, sponsored by Canadian distributor Fred Deeley Ltd., had nothing special going for it in comparison to the others, save for meticulous assembly and blueprinting by tuner Bob Work.

The Harley camp groaned, realizing they would spend the remaining three nights without sleep. The engines were torn down and reassembled again and again, then tested on a lonely road out in the Florida flatlands. None of the measurements seem to match specifications, and these were more critical than the tuners had dreamed. Carburetion was a shambles. False plug readings abounded. Changing megaphones to straight pipes and to reverse cones seemed to make no difference.

On Sunday it was raining, but it seemed that the race would run anyway. But, after practice, a large contingent of riders convinced AMA officials that racing in the rain would be too dangerous because of the gigantic rooster-tails thrown by the 150-mph bikes, and the constantly changing surfaces in the infield turns. So the race was delayed for one week. Much has been made of how the week-long delay benefited Harley, but the facts do not bear out such a statement. The two-strokes are quite skittish on wet surfaces, and lose traction without warning. The Harleys, as well as the other four-strokes, have heavier flywheels and may be accelerated in the wet with relative impunity. Several Yamaha riders, including du Hamel and Gould, admitted that they probably would not have finished in the rain, for their clutches already were slipping from the feathering necessary to exit from turns during wet practice. So it was all equal. Harley had time to recover its lost performance, and the two-strokes had time to replace their clutches...and they would run on dry pavement.

The first laps of the 200-miler had all the close-in excitement of a scratchers’ race at Brands. The lead changed an incredible 17 times in 19 laps. Du Hamel picked up early lap money, followed a few feet back by Rayborn, Gould, and 19-year-old Ron Pierce, on another fast running Yamaha. Both Gould and Rayborn drove to the front and switched places with du Hamel until the 10th lap, when Pierce drove around the whole bunch of them. While attempting to stretch his lead, Pierce went down on an oil slick from Dave Scott’s crashed Yamaha and broke his fairing. Du Hamel led again, but was passed by Rayborn. The tiny Canadian’s machine began showing signs of ignition failure in the 20th lap, and he pitted. His machine would not restart so he was out for keeps.

Back in the pack, several favorites dropped by the wayside with assorted mechanical woes.

Hammer’s Kawasaki got no farther than one lap, then seized a piston. Takeshi Araoka’s Kawasaki also retired somewhat later. Dick Mann rode with his usual great style after a poor start, then lost a gas cap from his Yamaha and could not get under way again after a pit stop. Ralph White’s Yamaha also died during a gas stop. Don Vesco suffered similar heartbreak after an exciting ride into 4th place. It was theorized that some of these failures may have been due to gasoline spilling onto the cylinders during refill, causing sudden contraction of the barrels and resultant partial seizure, ring damage and loss of compression.

In the Harley camp, Roger Reiman, who had dropped his bike in practice and damaged his clutch casing, retired with a foul smell after his clutch fried. Fred Nix’s bike, running too lean in the rear cylinder, melted a piston. Walt Fulton, one of the best road racers Harley has, yet on the slowest H-D, was running steadily at least, in contest with teammate Dan Haaby.

The trio of Suzuki 500s fared half bad, half good. Jimmy Odom ran well until a slack chain mangled the rear wheel sprocket. Art Baumann and Ron Grant linked up and “freight-trained” into the top four, then Art had to pit with broken expansion chambers. Grant then picked up 2nd spot as Gould, farther and farther behind Rayborn, pitted. Grant placed 2nd at the finish, but only after he met with near-disaster in his scheduled gas stop. His pit attendant failed to tighten the gas cap and, when gasoline sprayed from the tank as he left the pit apron, he fell. Fortunately, he was far enough ahead of 3rd place Mike Duff to push the Suzuki back for more gas, restart, and recapture 2nd place.

Rayborn finished at an average speed of 100.882 mph, slower than last year’s winning record.

Mert Lawwill, running on the same lap as Yamaha rider Duff, had inherited 4th. Another lap back, Englishman. Gould finished 5th after three pit stops. Bart Markel—oblivious to the fact that his rear brake disc had broken off completely—vindicated his unusually conservative tactics by coming in 6th, the first time he has even finished.

Most of the Triumphs and BSAs were noncompetitive, as these companies have been well out of the hunt since 1967 when Gary Nixon won Daytona. Thus it was somewhat amazing that AMA No. 1 Nixon motored to a 9th place finish, his engine sounding very ratty. Best of the BSAs was Eddie Wirth’s, and while Eddie is not a road racing specialist by any means, he rode smoothly to finish 20th.

Best of the Kawasakis was the 500-cc Three of Dave Simmonds, finishing in 17th. Also on the same lap and placing 19th was Bill Manley’s 500. It was not a bad performance, considering that the Three has only been in production a few short months.

In terms of national points, Rayborn’s 1st place gives him a great start on the AMA season. Markel’s prudence paid off well, giving him a nice bonus as he enters the summer season of halfmile nationals—his strongest card. Both Nixon and Lawwill also will be very much in the fray.

200-MILE EXPERT

250 AMATEUR/EXPERT

It is a wonder that Amateurs and Experts can race together in the 250 class, but cannot on big bikes. Many of the 250s are faster than the big bikes. But that is the AMA for you (the brands which control the AMA do not have 250s and, as for motocross, couldn’t care less what happens).

The two qualifying heats for the 250 race provided an insight to the sort of action expected in the 100-mile combined feature. The first heat was won by Yvon du Hamel, but the timer screwed up and stopped the clocks when the starter put the checker out, as du Hamel was lapping two slower riders. Consequently, time was measured from du Hamel’s start until an almost-lapped rider finished. So, officially, there is no official time for Yvon. Behind Yvon came another Canadian, Mike Duff; the Fred Deeley Yamahas already were setting the pace for others to follow. Third place went to Cal Rayborn on the bright green Kawasaki.

Ron Pierce, a Bakersfield, Calif., student, proved to everyone that the racing management at Yamaha International had made a good choice, despite this being Ron’s first year as an Expert. He ran away with the second heat race. A surprise 2nd place in the opening laps was Canada’s Dave Lloyd. Dave has raced in Europe, and even did a winter in California, racing in non-AM A events. Unfortunately Dave unloaded on Gould’s bend (Turn 3, a 100-mph sweeper) and although he escaped with a bad bruising, he was unable to race in the main event., England’s Rod Gould pulled through from the seventh row to take 2nd place behind Pierce. And Baumann, 3rd in the 200-miler last year, brought his green Kawasaki into 3rd place.

This meant the front half dozen in the lineup for the 100-mile 250 race would consist of three foreigners and three Californians, riding four Yamahas to two Kawasakis. As the flag dropped to start the feature, young Pierce gained 20 lengths in the first 10 seconds. Du Hamel forged ahead of Pierce on the long trip around the oval on Lap 1, and as the riders came into the infield to start the first real lap, it was du Hamel, Pierce, Duff, Gould, and Canadian Tim Coopey. Don Vesco was 10th, and carving through the pack. Also carving at an alarming rate was Cal Rayborn on his Kawasaki, as he passed three riders in Turn 1 to take 14th place. A lap later, Rayborn was in 6th place, and passing like mad through the infield portion of the circuit.

The fiery little du Hamel had gained one second on Pierce and three seconds on the Gould, Duff, Coopey group battling for 3rd place, as he came into the infield the second time. Previous 200 winner Ralph White was way down, after starting with his gas turned off. Gary Nixon also had lost a lap because of some misfortune on the grid. As engines were fired up for the clutch start, Dick Hammer had a great deal of trouble starting his Kawasaki, as did Dick Mann and Dickie Newell with their Yamahas. The pre-race problems seemed to hang on for the actual start, as all of these riders were back in the pack trying to make ground.

On the third tour, du Hamel, closely followed by Pierce, had pulled out eight seconds on the Gould-Duff affair, which Nixon was beginning to join. At this point Rayborn slipped into 5th spot, and teammate Baumann brought the second green screamer into 7th. Although down some 15 seconds on the leader, Rayborn was plowing through the field, and on the next lap passed both Nixon and Duff in the dangerous, decreasing radius first turn. By Lap 7, Rayborn was only four seconds behind Pierce, who had lost ground to du Hamel. Some 20 seconds down on the Nixon, Duff, Gould trio came the Coopey, Fulton, Camillieri, Baumann and Vesco quintet, no one giving an inch as they repassed constantly through the infield each lap.

On Lap 10, Rayborn dove inside Pierce in the sharp left out of the infield. Ken Aroaka, former winner of the Malaysian GP, and Kawasaki’s fourcylinder grand prix specialist, had worked his way up to 20th from a bad start, as he adjusted to the heavier production racing 250. Bobby Winters, winner in 1966, was having a big scrap with Dick Hammer for 14th place. Out on the oval, Pierce was able to pass Rayborn, only to lose ground as they screamed into the infield at horrible angles on the next lap.

Duff, Nixon and Gould were having a battle royal for 4th place. Almost every lap they would hurtle into Turn 1 abreast, braking and changing down almost in unison, and accelerate fiercely away to the 180-degree Turn 2. Rayborn and Pierce were pulling away from this group at something like a second per lap, and reduced du Hamel’s lead to 12 seconds on Lap 12. Don Vesco, apparently tired of following Camillieri and Coopey, passed them both on the 12th tour.

Du Hamel was still averaging more than 99.5 mph, and on a 250!

As the leader completed Lap 14, there were indications of rain. Rain at Daytona is like rain nowhere else, especially in the early stages, before the oil and rubber from numerous car races have been washed away. Even after considerable rain the surface is unpredictable. This year, too, the banking has deteriorated from the pounding imposed by the high-speed stock cars, and all of the 140-mph-plus machinery waggled badly. Despite the race’s premature ending last year, and the threatening, overcast skies this year, the AMA had no definite plan for inclement weather.

Consequently, when du Hamel approached the finish line on his 16th lap, the checkered flag went out, with no black flag. This meant the riders had no one-lap-to-go warning. Normally the black flag would have been used and positions would have been taken from the previous lap. Rayborn was in 3rd place one lap before the flag. Whether Rayborn could have held off the persistent Gould, if he had had a warning, is doubtful because of gear selector problems on his Kawasaki. Art Baumann crashed his Kawasaki at the first turn on his last lap when the rear brake anchor boss tore away from the backing plate.

So, it was the little French Canadian tiger, for the second consecutive year, averaging 98.348 mph. Yvon’s ride was flawless. Wet or dry, he was just on the verge of adhesion everywhere on the circuit. His sense of grip, whether braking or accelerating, is almost uncanny. The polished young Pierce went almost unnoticed in 2nd place, as he circulated alone after shaking the Rayborn menace. Rod Gould’s 3rd place proved it was not a fluke for a non-Yamaha International entry to win. In fact, Yamaha’s eight of the first 10 finishers was taken by one official team machine in 2nd place and another in 10th, with 8th place going to first Amateur Frank Camillieri.

It also is interesting to note that of the first 10 finishers only two learned their trade in AMA racing: Cal Rayborn in 4th and Bobby Winters in 10th. This is food for thought the next time the AMA considers suspending riders for competing in non-AMA races.

250-CC AMATEUR/EXPERT

100-MILE AMATEUR

Frank Camillieri, the Massachusetts road racer who does a great job in AAMRR (“Alphabet Association”) racing, was the fastest Amateur in qualifying, his Yamaha 350 posting a 134.831. It was hardly a clear-cut power grab, with Ron Muir (Yamaha) at 134.308; Art Ninci (H-D) at 133.432 and George Russell (Yamaha) at 132.081. Most astonishing was the fifth fastest qualifying time of 130.928 set by Ron (“Whispering”) Wakefield on a 500-cc Kawasaki Three that, to all ascertainable evidence, was completely stock, including street mufflers.

Muir took command from the start, and led all the way to a record average of 96.100 mph.

More exciting was “Whispering” Wakefield’s ride on that Three. He managed to stay in 2nd for several laps, albeit riding somewhat over his head, until the bike was slowed by detonation. Then, on Lap 7 he was passed by Art Ninci (H-D), Virgil Davenport (Triumph), and Ray Hempstead (Matchless G50). Wakefield finally retired when his clutch failed.

Davenport and Hempstead squeezed by Ninci, when the latter got into a wobble dashing off the straight into Turn 1, and the two continued to swap places.

George Russell (Yamaha) then drove through this group to 2nd place, but ran out of gas on the last lap! So at the finish it was Muir, Davenport and Hempstead in the first three places. Russell, who had gone 26 of 27 laps, still managed to place 4th, as the race stops when the checkered flag drops.

100-MILE AMA TEUR

NOVICE 250-CC RACE

This year’s Novice 250 was won at a speed considerably faster than the 1966 Amateur/Expert 250 event. In fact, the top Novice would have finished in the first 10 of the top-caliber 250 race this year. Harry Cone, a quiet, modest, 18-year-old high school senior, seemed content to watch the opposition for the first 30 miles, as the tigers came and went. At the halfway point of his 78-mile ride, the young Texan visibly turned up the wick and left his pursuers behind. In the opening stages it looked like fellow Texan Rusty Bradley might do the job. Recovering from a rather slow start, Bradley flew through the field on his Kawasaki, until Lap 5. On the fast left-hand Turn 3, Bradley overdid it, coming to rest at least 100 yards into the infield.

At this point we saw the typical Daytona disaster crew in action. An ambulance was necessary, granted. But instead of an ambulance to remove the rider, and then later a truck to remove the machine (or better still, why worry about the motorcycle? It’s not a very big target), three vehicles went to scene. Now this is no ordinary spot. It is, in fact, the very spot where a rider and his machine stopped after a crash. The AMA “blue hats” are all nervous about a photographer on the outside of a turn, but think nothing of parking three vehicles exactly where the next rider will crash. The ambulance left the area in six minutes and, for reasons we cannot understand, the two trucks stayed on the outside of Turn 3 for more than 10 minutes. Another case of the amount of mental constipation among the once-a-year demigods.

After Bradley expired, the coolheaded Cone had things all his own way and proceeded to pile up an unassailable lead on the remainder of the pack. Last year’s winner, Don Hollingsworth, had his H-D Sprint in the first three during the opening laps, but horsepower left its mark as he slowly dropped back from contention, and finally expired to be credited with 48th place. While running, Hollingsworth was the smoothest, most consistent rider in the race.

At the flag it was Cone by a half minute on Randolph Johnston, followed by Gary Fisher and Jerry Christopher. Yamaha only managed nine of the top 10 finishers in the Novice race. Maybe next year they will realize their ambition to take all of the top 10 in a Daytona race.

78-MILE NOVICE

SPORTSMAN 101-125CC

SPORTSMAN 100 CC

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

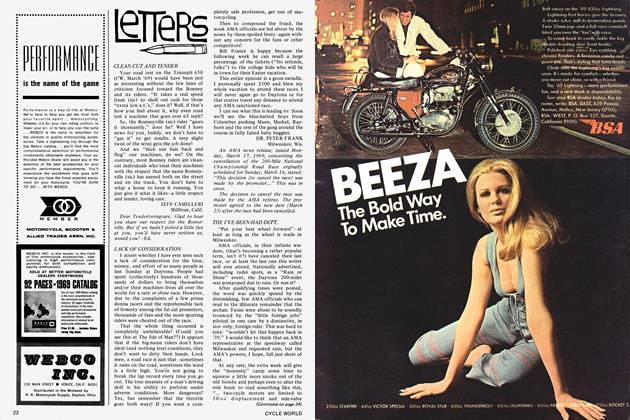

Round Up

June 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Scene

June 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

The Service Department

June 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1969 -

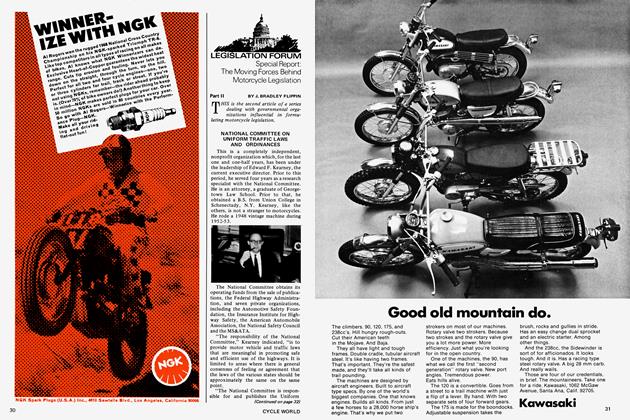

Legislation Forum

Legislation ForumSpecial Report: the Moving Forces Behind Motorcycle Legislation

June 1969 By J. Bradley Flippin -

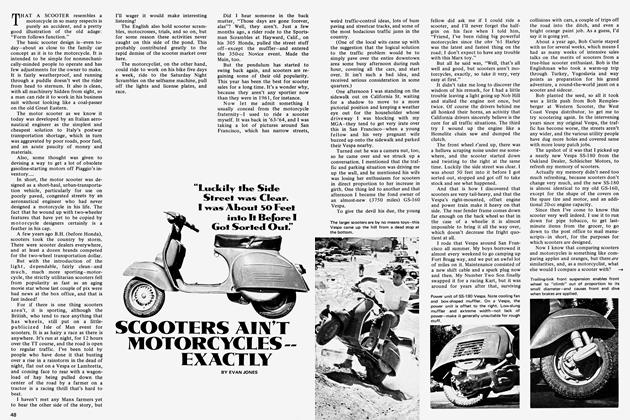

Offshoot Dept.

Offshoot Dept.Scooters Ain't Motorcycles-- Exactly

June 1969 By Evan Jones