Clipboard

RACE WATCH

Suzuka, 8 hours later

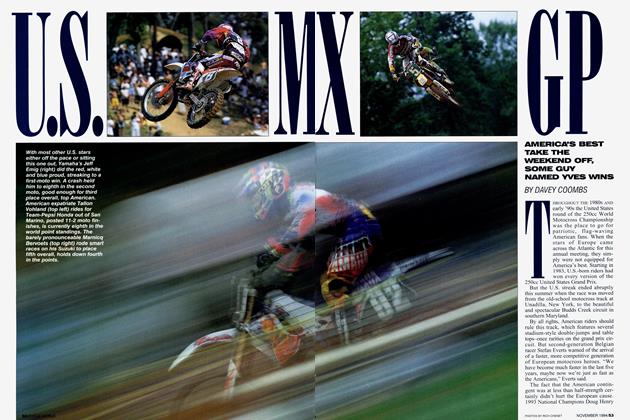

It may not be the longest of endurance races, but the Suzuka 8-Hour is certainly the most prestigious. Which explains why powerhouse Honda brought in the dream team of World Superbiker Colin Edwards and 500cc Grand Prix favorite Valentino Rossi for last July’s race.

Curiously, although Big Red did win the day, it wasn’t the Rossi/Edwards duo that walked away with the massive trophy. That particular glory was extended to Tohru Ukawa, for the third time in the last four years, and his teammate Daijiro Kato.

Yet at first, all eyes were on Edwards and Rossi. During the first session, the American swapped back and forth with Kawasaki’s Hitoyasu Izutsu. As Edwards handed over to Rossi and Izutsu to Akira Yanagawa, the battle continued. Then it seemed Rossi decided it was time to get down to business and opened a gap, but threw away the bike at low speed entering the Hairpin.

He got back to the pits, the bike minimally damaged, but ground was lost and a win was almost out of the question. In an attempt to make up that lost ground, Edwards threw away the bike as well. The team retired when the American complained of dizziness and nausea. He was taken to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with concussion.

Representing the Yamaha camp was spirited Noriyuki Haga and Waturu Yoshikawa. Haga’s claim to Suzuka fame was taking pole position during the race’s “Special Stages,” a qualifying process that inspired WSB’s Superpole. Unfortunately, Yoshikawa crashed and, as a result, the Yamaha team lost 22 minutes in the pits and 12 laps. This was too much for the charging Haga to recover, and they eventually finished 1 1th.

When the dust had settled, Ukawa and Kato were well-ensconced in first place. Second went to the incidentfree Suzuki of Akira Ryo and Keiichi Kitigawa. While never seeming to be on the pace, the Suzuki was always close. As others passed and fell, the GSX-R75()-mounted team just kept it in there and was rewarded. Third place went to Kawasaki’s Peter Goddard and Tamaki Serizawa.

One tragic incident marred the weekend. For the first time in the 23year-history of the Suzuka 8-Hour, a fatality occurred when 47-year-old privateer Mamoura Yamakawa crashed at the end of the back straight. This was Yamakawa’s 12th 8-Hour attempt.

Mark Wernham

Ricky Rules

Probably every dirtbike fan on the planet knows about Jeremy McGrath, the all-time King of Supercross who’s won seven 250cc SX titles. Likewise, almost every extreme-sports enthusiast in the world must know of 16-year-old Travis Pastrana, the charismatic Team Suzuki rider who doubles as the poster boy for ESPN’s X Games.

But almost lost in the mix of McGrath’s old fans and Pastrana’s new ones are the accomplishments of Havana, Florida’s Ricky Carmichael. As the 20-year-old leader of the Kawasaki/Chevy Trucks factory team, Carmichael is building a name for himself as possibly the best American motocross racer ever.

He won the AMA I25cc National MX Championship in each of his first three years, earning a recordtying 25 overall wins. Now, in his first year in the 250cc MX class, the diminutive Carmichael is proving that his abilities are not limited to 125s. At presstime, he was leading the 2000 AMA/Chevy Trucks U.S. National MX Championship.

The all-time record for career AMA National MX wins (37) was set by the legendary Bob “Hurricane” Hannah between 1976 and 1985. In fewer than four years, Carmichael’s career total is already up to 32 and counting.

Carmichael’s arrival at the top of the charts could not come at a better time for American fans. With a smallbut-strong contingent of French imports winning as many races as the rest of the Americans-Sebastien Tortelli and David Vuillemin are right behind Carmichael on the 250cc national circuit while Stephane Roncada is way out front in the 125cc classCarmichael has often been left to carry the flag by himself.

Carmichael’s deep desire to succeed goes back to his days as a minicycle prodigy. Often the shortest kid in the class, he built himself a reputation as one of the best mini racers ever. He won a record nine titles at Loretta Lynn’s Ranch, the site of the annual AMA Amateur National Championships.

Unfortunately, it’s that same ferocious appetite for winning races that has cost Carmichael success-and maybe some fans-on the 250cc Supercross circuit. For the last two years, he has struggled to control his speed on the tighter, more technical stadium tracks, and his crashes have come often. Carmichael is usually quiet and lighthearted, but he never seems able to mask his disappointment when he loses a race, let alone when he crashes out in front of 50,000 spectators.

“I just don’t care about getting second or third when I’m out there on the track,” says Carmichael of his hunger to win every time he goes to the starting gate. “The best way to win championships is to win races. For as long as I’ve been racing, I have been racing to win. That’s just the way I like to ride.”

A case in point is the recent outdoor round at Washougal, Washington. After crashing while leading early in the first moto, Carmichael battled from the back of the pack to finish second behind Team Yamaha’s Vuillemin. In the process, the Kawasaki rider padded his narrow points lead over Honda’s Tortelli, who finished fourth, in their duel for the numberone plate. But even with that added bonus, Carmichael could not hide his anger over his earlier mistake. When a reporter made reference to the fact that second place was 4 points better than Tortelli’s finish, Carmichael snapped, “I’m not interested in finishing second."

In a time of polished Supercross superstars, pre-packaged by their marketing people to be NASCAR-smooth, Carmichael’s rough-and-tumble exterior is a refreshing change of pace. (When was the last time you saw a rider doing a TV interview without his shirt, or even going on camera after the race with a dirty face and spitting a couple of times between answers?)

He’s already the fastest motocross racer on the planet, and once Carmichael figures out how to harness the throttle inside stadiums, that dirty, freckled face might also become the new look of Supercross.

Davey Coombs

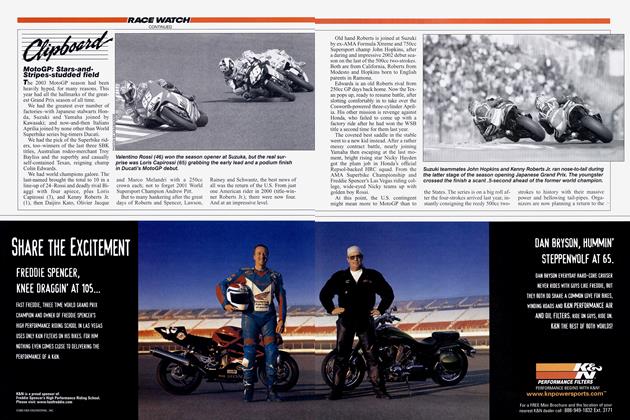

Rossi up and coming

Grand Prix racing’s midsummer break came after 10 of 16 races. Which means the second part of the season will be something of a sprint, in more than just the usual way. No prisoners, and-as yet-no foregone conclusions.

The first part of the new century’s season was a time of amazing variety in the premier 500cc class. Until the 10th round, only one rider had won more than a single race. That was Kenny Roberts Jr. on the Telefonica MoviStar Suzuki, and properly enough that meant he had a healthy points lead when he went home to Modesto, California, to relax and wonder whether Suzuki was going to come up with some more power for him.

The question was increasingly important, but not because of the danger posed by the man now lying third. Marlboro Yamaha’s Carlos Checa had been dropping back ever since the early part of the year, and even seemed to be reviving his 1999 reputation as a frequent faller after having achieved enviable consistency.

Instead, the threat to Roberts’ first world title was coming from another quarter-a pair of Hondas, ridden by the new star of the class Valentino Rossi, and Alex Barros, who narrowly fended off the importunate youngster at the 10th round in Germany to win his second race of the year.

“Trouble with those Hondas,” growled Roberts, “is you can’t see how talented the people riding them are. If the setup is good, they only have to ride them half-decent.”

This seemed a little unfair to nascent supernova Rossi, who joined the class as a novice, albeit with a fresh 250cc title in his pocket alongside his earlier 125cc crown. By the ninth race, however, he’d mastered his Nastro Azzurro-sponsored NSR so well that he could claim his first win (over Roberts and V-Twin Aprilia rider Jeremy McWilliams) in a wet race in England.

Can Rossi catch Roberts before the season is out? Possibly. Roberts’ nightmare must be just one more nonfinish-like the first-lap engine seizure that sent him looping over the handlebars and out of the points in the Dutch TT at Assen.

Rossi's blaze to glory has quite overshadowed some other fancied runners. Defending Champion Alex Criville has won a single race, but along with his teammates in the factory Repsol Honda team has succumbed to a strange malady of being unable to get his bike set-up to his satisfaction. Result: lots of crashes, and no hope in the championship. Much the same has afflicted Max Biaggi on the other factory Yamaha. Meanwhile, early GP winner Garry McCoy (Red Bull Yamaha) has dropped out of touch after several bad gambles on tire choice in a season when bad weather has played a role in nine out of 10 rounds.

The way it’s going, only by the very last lap of the final race of the season will this year’s champion be known.

Michael Scott

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontShameless Plugs

November 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Convertible

November 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCGp Four-Strokes

November 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

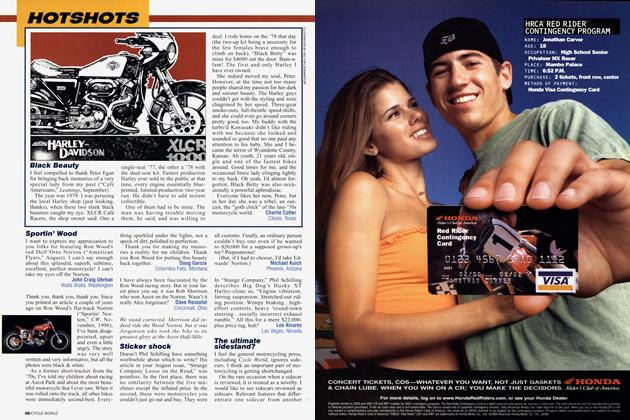

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupDan Gurney's Alligator: Alternative Corner Carver

November 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupHart Attack

November 2000 By Eric Johnson