Remaking Triumph

UP FRONT

David Edwards

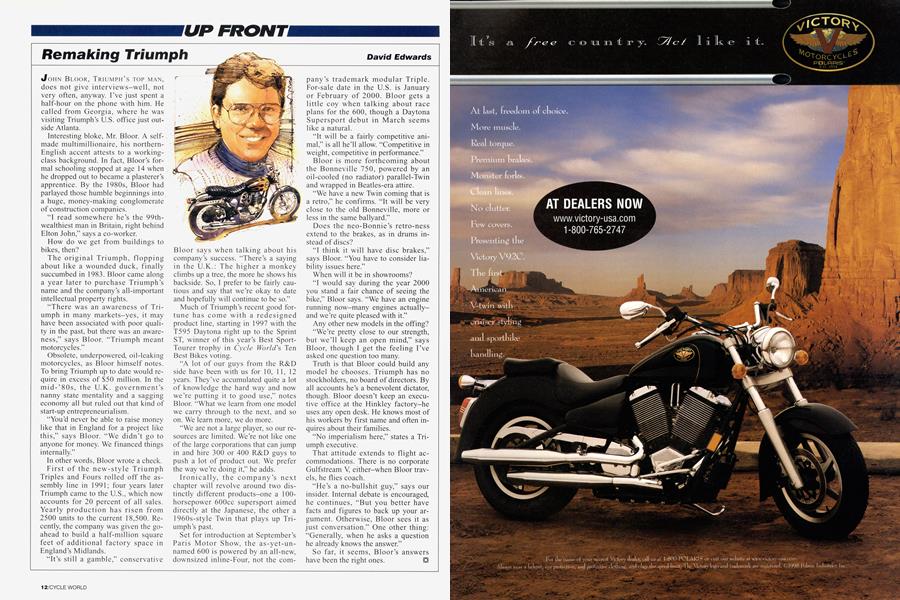

JOHN BLOOR, TRIUMPH’S TOP MAN,R does not give interviews-well, not very often, anyway. I’ve just spent a half-hour on the phone with him. He called from Georgia, where he was visiting Triumph’s U.S. office just outside Atlanta.

Interesting bloke, Mr. Bloor. A selfmade multimillionaire, his northernEnglish accent attests to a workingclass background. In fact, Bloor’s formal schooling stopped at age 14 when he dropped out to became a plasterer’s apprentice. By the 1980s, Bloor had parlayed those humble beginnings into a huge, money-making conglomerate of construction companies.

“I read somewhere he’s the 99thwealthiest man in Britain, right behind Elton John,” says a co-worker.

How do we get from buildings to bikes, then?

The original Triumph, flopping about like a wounded duck, finally succumbed in 1983. Bloor came along a year later to purchase Triumph's name and the company's all-important intellectual property rights.

"There was an awareness of Tri umph in many markets-yes, it may have been associated with poor quali ty in the past, but there was an aware ness," says Bloor. "Triumph meant motorcycles."

Obsolete, underpowered, oil-leaking motorcycles, as Bloor himself notes. To bring Triumph up to date would re quire in excess of $50 million. In the mid-'80s, the U.K. government's nanny state mentality and a sagging economy all but ruled out that kind of start-up entrepreneurialism.

"You'd never be able to raise money like that in England for a project like this," says Bloor. "We didn't go to anyone for money. We financed things internally."

In other words, Bloor wrote a check. First of the new-style Triumph Triples and Fours rolled off the as sembly line in 1991; four years later Triumph came to the U.S., which now accounts for 20 percent of all sales. Yearly production has risen from 2500 units to the current 18,500. Re cently, the company was given the go ahead to build a half-million square feet of additional factory space in England's Midlands.

"It's still a gamble," conservative Bloor says when talking about his company's success. "There's a saying in the U.K.: The higher a monkey climbs up a tree, the more he shows his backside. So, I prefer to be fairly cau tious and say that we're okay to date and hopefully will continue to be so."

Much of Triumph `s recent good for tune has come with a redesigned product line, starting in 1997 with the T595 Daytona right up to the Sprint SI, winner of this year's Best Sport Tourer trophy in Cycle World's Ten Best Bikes voting.

"A lot of our guys from the R&D side have been with us for 10, 11, 12 years. They've accumulated quite a lot of knowledge the hard way and now we're putting it to good use," notes Bloor. "What we learn from one model we carry through to the next, and so on. We learn more, we do more.

"We are not a large player, so our re sources are limited. We're not like one of the large corporations that can jump in and hire 300 or 400 R&D guys to push a lot of product out. We prefer the way we're doing it," he adds.

Ironically, the company's next chapter will revolve around two dis tinctly different products-one a 100horsepower 600cc supersport aimed directly at the Japanese, the other a 1960s-style Twin that plays up Tri umph's past.

Set for introduction at September's Paris Motor Show, the as-yet-un named 600 is powered by an all-new, downsized inline-Four, not the cornpany’s trademark modular Triple. For-sale date in the U.S. is January or February of 2000. Bloor gets a little coy when talking about race plans for the 600, though a Daytona Supersport debut in March seems like a natural.

“It will be a fairly competitive animal,” is all he’ll allow. “Competitive in weight, competitive in performance.” Bloor is more forthcoming about the Bonneville 750, powered by an oil-cooled (no radiator) parallel-Twin and wrapped in Beatles-era attire.

“We have a new Twin coming that is a retro,” he confirms. “It will be very close to the old Bonneville, more or less in the same ballyard.”

Does the neo-Bonnie’s retro-ness extend to the brakes, as in drums instead of discs?

“I think it will have disc brakes,” says Bloor. “You have to consider liability issues here.”

When will it be in showrooms?

“I would say during the year 2000 you stand a fair chance of seeing the bike,” Bloor says. “We have an engine running now-many engines actuallyand we’re quite pleased with it.”

Any other new models in the offing? “We’re pretty close to our strength, but we’ll keep an open mind,” says Bloor, though I get the feeling I’ve asked one question too many.

Truth is that Bloor could build any model he chooses. Triumph has no stockholders, no board of directors. By all accounts he’s a benevolent dictator, though. Bloor doesn’t keep an executive office at the Hinkley factory-he uses any open desk. He knows most of his workers by first name and often inquires about their families.

“No imperialism here,” states a Triumph executive.

That attitude extends to flight accommodations. There is no corporate Gulfstream V, either-when Bloor travels, he flies coach.

“He’s a no-bullshit guy,” says our insider. Internal debate is encouraged, he continues, “But you better have facts and figures to back up your argument. Otherwise, Bloor sees it as just conversation.” One other thing: “Generally, when he asks a question he already knows the answer.”

So far, it seems, Bloor’s answers have been the right ones.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue