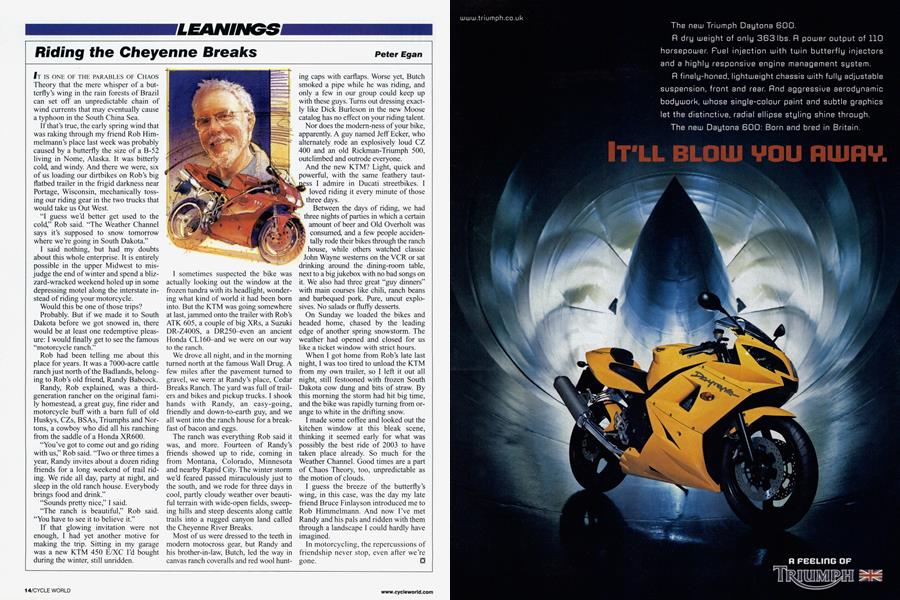

Riding the Cheyenne Breaks

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

IT IS ONE OF THE PARABLES OF CHAOS Theory that the mere whisper of a butterfly’s wing in the rain forests of Brazil can set off an unpredictable chain of wind currents that may eventually cause a typhoon in the South China Sea.

If that’s true, the early spring wind that was raking through my friend Rob Himmelmann’s place last week was probably caused by a butterfly the size of a B-52 living in Nome, Alaska. It was bitterly cold, and windy. And there we were, six of us loading our dirtbikes on Rob’s big flatbed trailer in the frigid darkness near Portage, Wisconsin, mechanically tossing our riding gear in the two trucks that would take us Out West.

“I guess we’d better get used to the cold,” Rob said. “The Weather Channel says it’s supposed to snow tomorrow where we’re going in South Dakota.”

I said nothing, but had my doubts about this whole enterprise. It is entirely possible in the upper Midwest to misjudge the end of winter and spend a blizzard-wracked weekend holed up in some depressing motel along the interstate instead of riding your motorcycle.

Would this be one of those trips? Probably. But if we made it to South Dakota before we got snowed in, there would be at least one redemptive pleasure: I would finally get to see the famous “motorcycle ranch.”

Rob had been telling me about this place for years. It was a 7000-acre cattle ranch just north of the Badlands, belonging to Rob’s old friend, Randy Babcock.

Randy, Rob explained, was a thirdgeneration rancher on the original family homestead, a great guy, fine rider and motorcycle buff with a bam full of old Huskys, CZs, BSAs, Triumphs and Nortons, a cowboy who did all his ranching from the saddle of a Honda XR600.

“You’ve got to come out and go riding with us,” Rob said. “Two or three times a year, Randy invites about a dozen riding friends for a long weekend of trail riding. We ride all day, party at night, and sleep in the old ranch house. Everybody brings food and drink.”

“Sounds pretty nice,” I said.

“The ranch is beautiful,” Rob said. “You have to see it to believe it.”

If that glowing invitation were not enough, I had yet another motive for making the trip. Sitting in my garage was a new KTM 450 E/XC I’d bought during the winter, still unridden.

I sometimes suspected the bike was actually looking out the window at the frozen tundra with its headlight, wondering what kind of world it had been born into. But the KTM was going somewhere at last, jammed onto the trailer with Rob’s ATK 605, a couple of big XRs, a Suzuki DR-Z400S, a DR250-even an ancient Honda CL160-and we were on our way to the ranch.

We drove all night, and in the morning turned north at the famous Wall Drug. A few miles after the pavement turned to gravel, we were at Randy’s place, Cedar Breaks Ranch. The yard was full of trailers and bikes and pickup trucks. I shook hands with Randy, an easy-going, friendly and down-to-earth guy, and we all went into the ranch house for a breakfast of bacon and eggs.

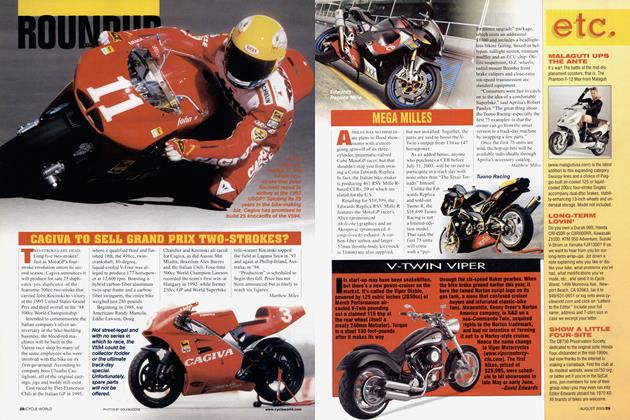

The ranch was everything Rob said it was, and more. Fourteen of Randy’s friends showed up to ride, coming in from Montana, Colorado, Minnesota and nearby Rapid City. The winter storm we’d feared passed miraculously just to the south, and we rode for three days in cool, partly cloudy weather over beautiful terrain with wide-open fields, sweeping hills and steep descents along cattle trails into a rugged canyon land called the Cheyenne River Breaks.

Most of us were dressed to the teeth in modern motocross gear, but Randy and his brother-in-law, Butch, led the way in canvas ranch coveralls and red wool hunting caps with earflaps. Worse yet, Butch smoked a pipe while he was riding, and only a few in our group could keep up with these guys. Turns out dressing exactly like Dick Burleson in the new Moose catalog has no effect on your riding talent.

Nor does the modem-ness of your bike, apparently. A guy named Jeff Ecker, who alternately rode an explosively loud CZ 400 and an old Rickman-Triumph 500, outclimbed and outrode everyone.

And the new KTM? Light, quick and powerful, with the same feathery tautss I admire in Ducati streetbikes. I loved riding it every minute of those three days.

Between the days of riding, we had three nights of parties in which a certain amount of beer and Old Overholt was consumed, and a few people accidentally rode their bikes through the ranch house, while others watched classic John Wayne westerns on the VCR or sat drinking around the dining-room table, next to a big jukebox with no bad songs on it. We also had three great “guy dinners” with main courses like chili, ranch beans and barbequed pork. Pure, uncut explosives. No salads or fluffy desserts.

On Sunday we loaded the bikes and headed home, chased by the leading edge of another spring snowstorm. The weather had opened and closed for us like a ticket window with strict hours.

When I got home from Rob’s late last night, I was too tired to unload the KTM from my own trailer, so I left it out all night, still festooned with frozen South Dakota cow dung and bits of straw. By this morning the storm had hit big time, and the bike was rapidly turning from orange to white in the drifting snow.

I made some coffee and looked out the kitchen window at this bleak scene, thinking it seemed early for what was possibly the best ride of 2003 to have taken place already. So much for the Weather Channel. Good times are a part of Chaos Theory, too, unpredictable as the motion of clouds.

I guess the breeze of the butterfly’s wing, in this case, was the day my late friend Bruce Finlayson introduced me to Rob Himmelmann. And now I’ve met Randy and his pals and ridden with them through a landscape I could hardly have imagined.

In motorcycling, the repercussions of friendship never stop, even after we’re gone. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue