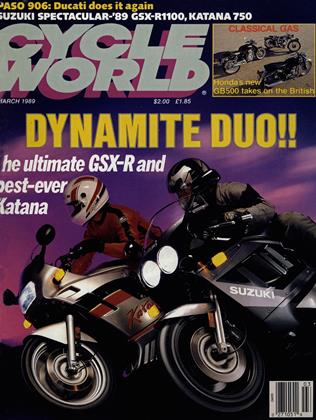

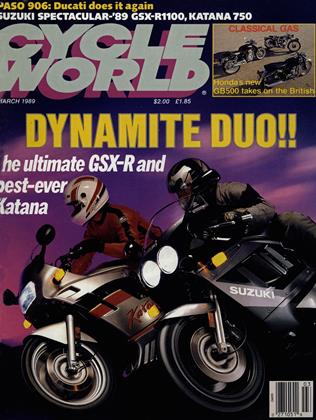

The perfect touring bike

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

I’M TOLD THAT IF YOU LIVE IN CALIfornia too long and don’t visit the Gold Country, the Bureau of Tourism will come and revoke your state citizenship and make you move to a flat place with no curving roads or scenic vistas. Homage must be paid. Having lived here for eight years, my wife Barbara and I finally decided a few weeks ago that it was Time.

With a four-day weekend vacation on tap, we loaded the saddlebags and tank bag onto our new/used Bimmer and got ready to head for the hills. We’d taken only a few short rides together on the R80 and wanted to see if it might make the ideal mount for a much longer trip we have planned for next year—a tour of British Columbia and the greater Northwest.

The first leg of any trip away from the greater Los Angeles area is strategically similar to breaking out of San Quentin, with heavy reliance on cover of darkness. To beat the rush hour, we got up at 4:30, hit the freeways and rode like crazy through darkness and fog and headlights for three hours until sunlight finally burst upon us just south of Bakersfield, where we stopped for breakfast.

Barb got off the bike looking a little cold and stiff. “Whatever you do,” she said, turning toward the cafe, “don’t sell the Kawasaki.”

She was referring to our trusty old KZ1000 MKII. “Why do you say that?” I inquired, fearing the worst.

“Because the Kawasaki has a really comfortable seat, and this one is only fair. It’s way too hard, and you slide downhill all the time.”

Interesting. The BMW did many things well, but its soul was essentially that of a long-distance tourer. Yet here was Barb, telling me that the seat compared unfavorably to that of an 8-year-old Japanese sportbike.

I patiently explained to her that the motorcycle industry had, in the past few years, forgotten how to make a comfortable two-up saddle on any machine weighing and/or costing less than a new Honda Civic, and that the BMW was practically the last sporttourer on earth that even pretended you could carry a passenger for any distance.

“I know,” she said, “that’s why I don’t want you to sell the Kawasaki. We’ll never be able to find another bike that comfortable, unless we get some great big thing with radios and a trailer.”

The front half of the saddle—my half—felt fine, but I made a mental note, in the name of domestic tranquility, to look into buying a slightly more padded aftermarket seat when we got home. Onward to the Gold Country.

We rode up Highway 41 and at Oakhurst finally hit Highway 49, the famous road that links the historic gold-mining towns along the west side of the Sierra Nevada. Here I felt the BMW was in its element, tilting through the sweeping curves with easy agility, spinning smoothly in the middle of its torque curve and whispering down the main streets of such colorful old villages as Coulterville and Chinese Camp. When we stopped for lunch at Angels Camp, I asked Barb how it was going.

“Fine,” she said, “but this bike sure doesn’t have much power. It takes forever to pass a car when we’re going uphill. Not like the Kawasaki.”

It was true that passing cars on a mountain road with the Kawasaki was sort of like pulling a trigger, while the R80 needed a few moments to gather speed. But then it was an 800cc Twin rather than a lOOOcc Four. I tried to explain to Barb that a big Twin might be slower than a highly-tuned Four, but that a Twin had entertainment value; it sounded neat going down the road and made you feel good. It was all tied in with charm, character and a sense of pace.

“I suppose . . .” she said. “Still, I wish we could get around those motorhomes faster.”

I made a second mental note. When we got home I would look into the cost of installing the big lOOOcc jugs on the R80. My friend John Joss had done it and said it was easy, just a barrel and piston swap, and not very expensive.

We spent the next two days riding through absolutely beautiful mountain and pine-forest country. We stopped at the rustic old Murphys Hotel in Murphys on Friday night, and spent the next night at the equally charming St. George Hotel in the tiny village of Volcano, the latter establishment having triple-decker porches with a good drink-sipping view, and a dining room where the food is cooked by a woman named Sarah who can really cook. On Sunday we crossed the mountains over Pacific Grade Summit (el. 8050) on Highway 4, one of the great motorcycle roads of all time.

After a short stop at the surreal, windswept Bodie ghost town, we took Highway 395 back toward LA. This is a road that gets hotter, flatter and duller as you head south—a good case for roadside molecular transmigration booths that beam you instantly back to your own garage, saving hours of boredom. When we stopped at Red Mountain for a cold drink, I asked Barb how it was going.

“Fine,” she said, “but the engine sounds as if it’s running too fast when you go more than 70 on the highway, like it needs another gear. Also, I wish we had a fairing. That wind wears you out after a few hours.”

I explained that Twins actually have a more relaxed gait than Fours, even though they are still turning the same rpm, because there are fewer firing pulses, and so on. Barb shrugged. “It just feels noisy and windy.”

So. I made a third mental note, to see about replacing the R80’s 3.20 differential with the taller 3.0 rear end from the R100RS. And while I was at the parts counter, I might also check on the cost of an R100RS fairing, to cut down the wind fatique.

I figured that if I replaced the seat and the cylinders and the differential and added the fairing, I’d have a nearly perfect touring bike. It wouldn’t be quite as light, smooth and agile as the R80 or as powerful as the Kawasaki, but it would be a pretty good replica of the R100RS. Which was the bike I almost bought instead of the R80, but didn’t, of course, because it cost more money.