Slow seduction

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

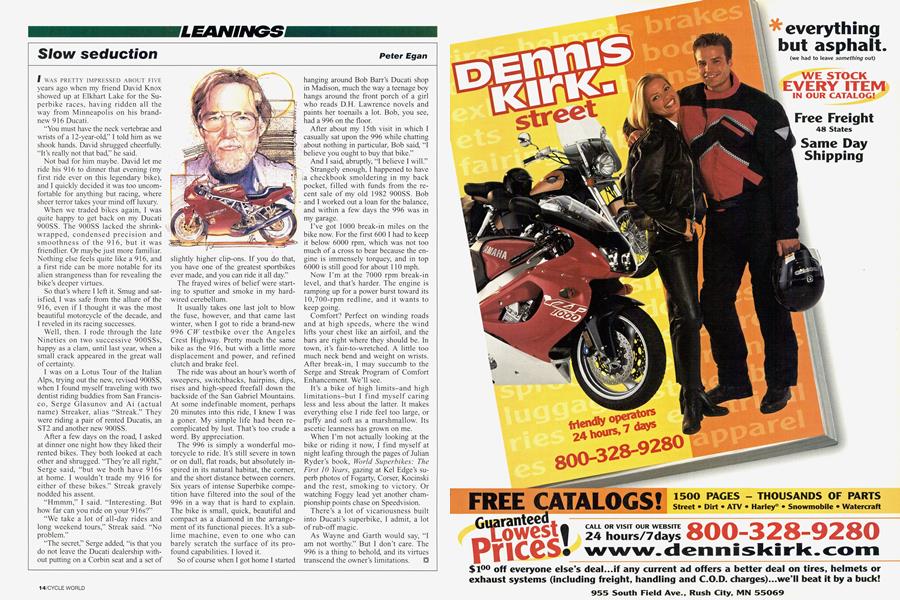

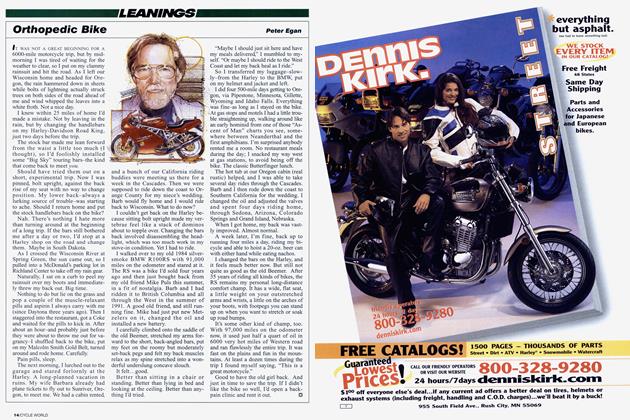

I WAS PRETTY IMPRESSED ABOUT FIVE years ago when my friend David Knox showed up at Elkhart Lake for the Superbike races, having ridden all the way from Minneapolis on his brand-new 916 Ducati.

“You must have the neck vertebrae and wrists of a 12-year-old,” I told him as we shook hands. David shrugged cheerfully. “It’s really not that bad,” he said.

Not bad for him maybe. David let me ride his 916 to dinner that evening (my first ride ever on this legendary bike), and I quickly decided it was too uncomfortable for anything but racing, where sheer terror takes your mind off luxury.

When we traded bikes again, I was quite happy to get back on my Ducati 900SS. The 900SS lacked the shrinkwrapped, condensed precision and smoothness of the 916, but it was friendlier. Or maybe just more familiar. Nothing else feels quite like a 916, and a first ride can be more notable for its alien strangeness than for revealing the bike’s deeper virtues.

So that’s where I left it. Smug and satisfied, I was safe from the allure of the 916, even if I thought it was the most beautiful motorcycle of the decade, and I reveled in its racing successes.

Well, then. I rode through the late Nineties on two successive 900SSs, happy as a clam, until last year, when a small crack appeared in the great wall of certainty.

I was on a Lotus Tour of the Italian Alps, trying out the new, revised 900SS, when I found myself traveling with two dentist riding buddies from San Lrancisco, Serge Glasunov and Ai (actual name) Streaker, alias “Streak.” They were riding a pair of rented Ducatis, an ST2 and another new 900SS.

After a few days on the road, I asked at dinner one night how they liked their rented bikes. They both looked at each other and shrugged. “They’re all right,” Serge said, “but we both have 916s at home. I wouldn’t trade my 916 for either of these bikes.” Streak gravely nodded his assent.

“Hmmm,” I said. “Interesting. But how far can you ride on your 916s?”

“We take a lot of all-day rides and long weekend tours,” Streak said. “No problem.”

“The secret,” Serge added, “is that you do not leave the Ducati dealership without putting on a Corbin seat and a set of slightly higher clip-ons. If you do that, you have one of the greatest sportbikes ever made, and you can ride it all day.”

The frayed wires of belief were starting to sputter and smoke in my hardwired cerebellum.

It usually takes one last jolt to blow the fuse, however, and that came last winter, when I got to ride a brand-new 996 CW testbike over the Angeles Crest Highway. Pretty much the same bike as the 916, but with a little more displacement and power, and refined clutch and brake feel.

The ride was about an hour’s worth of sweepers, switchbacks, hairpins, dips, rises and high-speed freefall down the backside of the San Gabriel Mountains. At some indefinable moment, perhaps 20 minutes into this ride, I knew I was a goner. My simple life had been recomplicated by lust. That’s too crude a word. By appreciation.

The 996 is simply a wonderful motorcycle to ride. It’s still severe in town or on dull, flat roads, but absolutely inspired in its natural habitat, the corner, and the short distance between corners. Six years of intense Superbike competition have filtered into the soul of the 996 in a way that is hard to explain. The bike is small, quick, beautiful and compact as a diamond in the arrangement of its functional pieces. It’s a sublime machine, even to one who can barely scratch the surface of its profound capabilities. I loved it.

So of course when I got home I started hanging around Bob Barr’s Ducati shop in Madison, much the way a teenage boy hangs around the front porch of a girl who reads D.H. Lawrence novels and paints her toenails a lot. Bob, you see, had a 996 on the floor.

After about my 15th visit in which I casually sat upon the 996 while chatting about nothing in particular, Bob said, “I believe you ought to buy that bike.”

And I said, abruptly, “I believe I will.”

Strangely enough, I happened to have ;a checkbook smoldering in my back pocket, filled with funds from the recent sale of my old 1982 900SS. Bob and I worked out a loan for the balance, and within a few days the 996 was in my garage.

I’ve got 1000 break-in miles on the bike now. Lor the first 600 I had to keep it below 6000 rpm, which was not too much of a cross to bear because the engine is immensely torquey, and in top 6000 is still good for about 110 mph.

Now I’m at the 7000 rpm break-in level, and that’s harder. The engine is ramping up for a power burst toward its 10,700-rpm redline, and it wants to keep going.

Comfort? Perfect on winding roads and at high speeds, where the wind lifts your chest like an airfoil, and the bars are right where they should be. In town, it’s fair-to-wretched. A little too much neck bend and weight on wrists. After break-in, I may succumb to the Serge and Streak Program of Comfort Enhancement. We’ll see.

It’s a bike of high limits-and high limitations-but I find myself caring less and less about the latter. It makes everything else I ride feel too large, or puffy and soft as a marshmallow. Its ascetic leanness has grown on me.

When I’m not actually looking at the bike or riding it now, I find myself at night leafing through the pages of Julian Ryder’s book, World Superbikes: The First 10 Years, gazing at Kel Edge’s superb photos of Logarty, Corser, Kocinski and the rest, smoking to victory. Or watching Loggy lead yet another championship points chase on Speedvision.

There’s a lot of vicariousness built into Ducati’s superbike, I admit, a lot of rub-off magic.

As Wayne and Garth would say, “I am not worthy.” But I don’t care. The 996 is a thing to behold, and its virtues transcend the owner’s limitations.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue