In Memorium

LEANINGS

AFTER THE FUNERAL SERVICE, ALLAN Girdler and I walked around to the back parking lot of the church and climbed into my van for the drive to the cemetery. Somehow, we lost track of the funeral procession in the labyrinth of suburban streets in Corona del Mar. We'd just pulled over to consult a map when a beautifully restored Triumph 650 and sidecar rig rumbled past, ridden by a man in a suit and sunglasses. "Follow that bike," Allan said. "Unless I'm wrong, that guy is a friend of Henry's and is on his way to the cemetery."

He was indeed, and the burbling exhaust note of his lovely old Speed Twin led us right to the cemetery. Rescued by a British bike; Henry would have loved it.

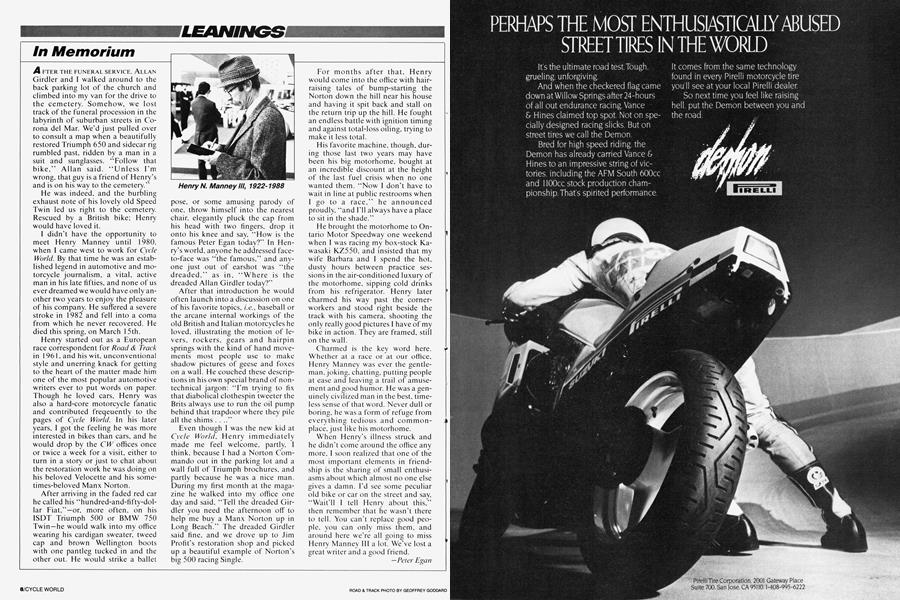

I didn’t have the opportunity to meet Henry Manney until 1980, when I came west to work for Cycle World. By that time he was an established legend in automotive and motorcycle journalism, a vital, active man in his late fifties, and none of us ever dreamed we would have only another two years to enjoy the pleasure of his company. He suffered a severe stroke in 1982 and fell into a coma from which he never recovered. He died this spring, on March 1 5th.

Henry started out as a European race correspondent for Road & Track in 1961, and his wit, unconventional style and unerring knack for getting to the heart of the matter made him one of the most popular automotive writers ever to put words on paper. Though he loved cars, Henry was also a hard-core motorcycle fanatic and contributed freqeuently to the pages of Cycle World. In his later years, I got the feeling he was more interested in bikes than cars, and he would drop by the CW offices once or twice a week for a visit, either to turn in a story or just to chat about the restoration work he was doing on his beloved Velocette and his sometimes-beloved Manx Norton.

After arriving in the faded red car he called his “hundred-and-fifty-dollar Fiat,”—or, more often, on his ISDT Triumph 500 or BMW 750 Twin —he would walk into my office wearing his cardigan sweater, tweed cap and brown Wellington boots with one pantleg tucked in and the other out. He would strike a ballet

pose, or some amusing parody of one, throw himself into the nearest chair, elegantly pluck the cap from his head with two fingers, drop it onto his knee and say, “How is the famous Peter Egan today?” In Henry’s world, anyone he addressed faceto-face was “the famous,” and anyone just out of earshot was “the dreaded,” as in, “Where is the dreaded Allan Girdler today?”

After that introduction he would often launch into a discussion on one of his favorite topics, i.e., baseball or the arcane internal workings of the old British and Italian motorcycles he loved, illustrating the motion of levers, rockers, gears and hairpin springs with the kind of hand movements most people use to make shadow pictures of geese and foxes on a wall. He couched these descriptions in his own special brand of nontechnical jargon: “I’m trying to fix that diabolical clothespin tweeter the Brits always use to run the oil pump behind that trapdoor where they pile all the shims . . ..”

Even though I was the new kid at Cycle World, Henry immediately made me feel welcome, partly, I think, because I had a Norton Commando out in the parking lot and a wall full of Triumph brochures, and partly because he was a nice man. During my first month at the magazine he walked into my office one day and said, “Tell the dreaded Girdler you need the afternoon off to help me buy a Manx Norton up in Long Beach.” The dreaded Girdler said fine, and we drove up to Jim Profit’s restoration shop and picked up a beautiful example of Norton’s big 500 racing Single.

For months after that, Henry would come into the office with hairraising tales of bump-starting the Norton down the hill near his house and having it spit back and stall on the return trip up the hill. He fought an endless battle with ignition timing and against total-loss oiling, trying to make it less total.

His favorite machine, though, during those last two years may have been his big motorhome, bought at an incredible discount at the height of the last fuel crisis when no one wanted them. “Now I don’t have to wait in line at public restrooms when I go to a race,” he announced proudly, “and I’ll always have a place to sit in the shade.”

He brought the motorhome to Ontario Motor Speedway one weekend when I was racing my box-stock Kawasaki KZ550. and insisted that my wife Barbara and I spend the hot, dusty hours between practice sessions in the air-conditioned luxury of the motorhome, sipping cold drinks from his refrigerator. Henry later charmed his way past the cornerworkers and stood right beside the track with his camera, shooting the only really good pictures I have of my bike in action. They are framed, still on the wall.

Charmed is the key word here. Whether at a race or at our office, Henry Manney was ever the gentleman, joking, chatting, putting people at ease and leaving a trail of amusement and good humor. He was a genuinely civilized man in the best, timeless sense of that word. Never dull or boring, he was a form of refuge from everything tedious and commonplace, just like his motorhome.

When Henry’s illness struck and he didn’t come around the office any more, I soon realized that one of the most important elements in friendship is the sharing of small enthusiasms about which almost no one else gives a damn. I’d see some peculiar old bike or car on the street and say, “Wait'll I tell Henry about this,” then remember that he wasn’t there to tell. You can't replace good people, you can only miss them, and around here we're all going to miss Henry Manney III a lot. We’ve lost a great writer and a good friend.

Peter Egan

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialThe Game of the Name

August 1988 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Times They Are A-Changin'

August 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

August 1988 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupDestinations

August 1988 By Ron Lawson -

Features

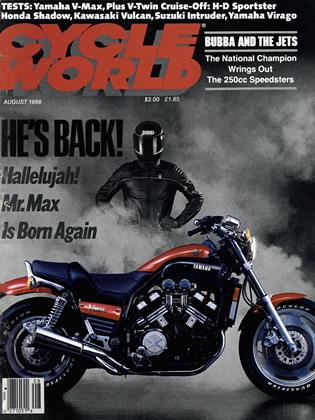

FeaturesBig Max Attack

August 1988 By David Edwards