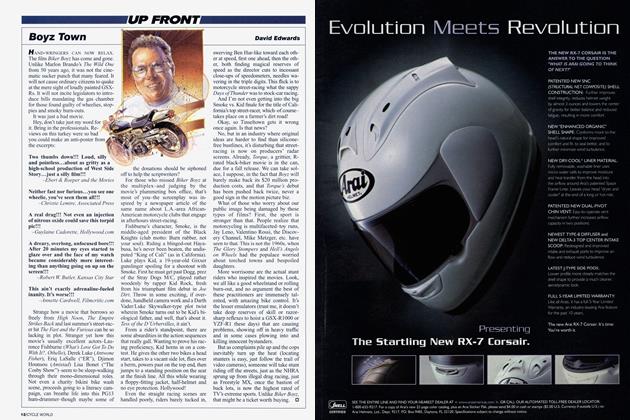

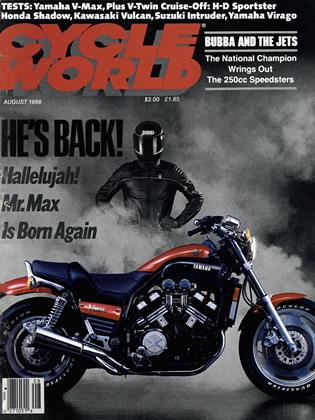

BIG MAX ATTACK

Faster than the speed of fright

DAVID EDWARDS

I HAD BEEN THIS NERVOUS BEFORE, BUT THAT WAS THE time I found myself a half-mile above the earth, white-knuckling a Cessna 172's Wing strut while a jumpmaster tried to persude me that, yes, I really did want to let go. This time, it was a Yamaha V-Max that was giving me an anxiety attack.

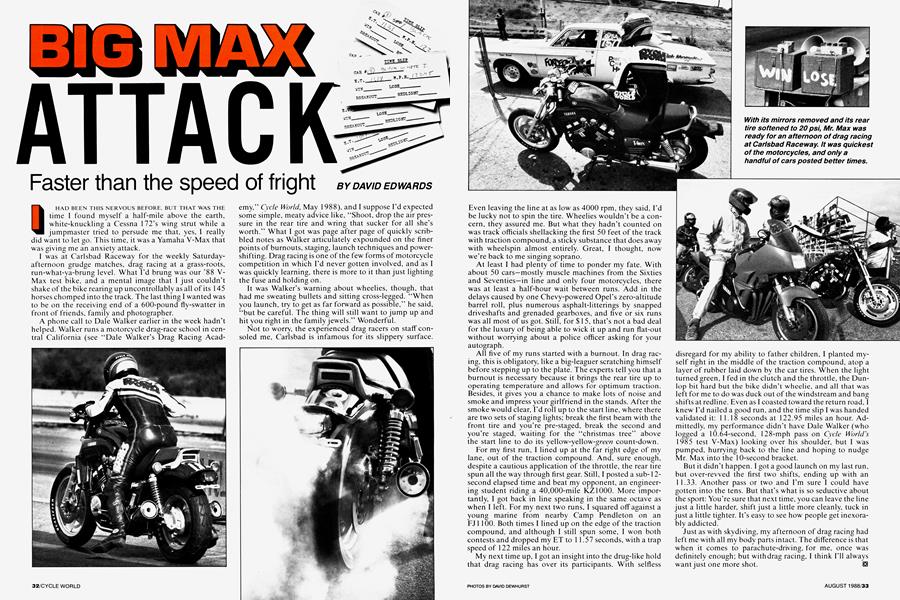

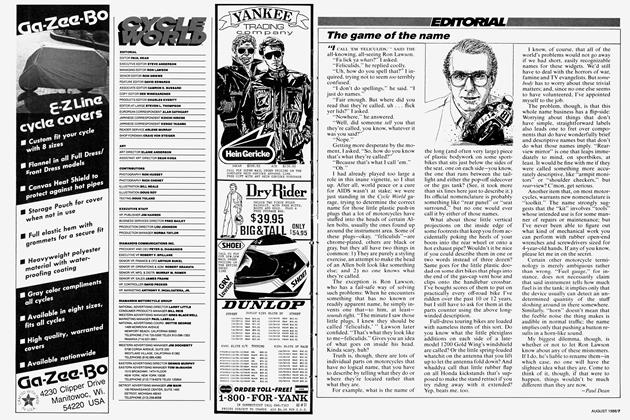

I was at Carlsbad Raceway for the weekly Saturdayafternoon grudge matches, drag racing at a grass-roots, run-what-ya-brung level. What I’d brung was our ’88 VMax test bike, and a mental image that I just couldn’t shake of the bike rearing up uncontrollably as all of its 145 horses chomped into the track. The last thing I wanted was to be on the receiving end of a 600-pound fly-swatter in front of friends, family and photographer.

A phone call to Dale Walker earlier in the week hadn’t helped. Walker runs a motorcycle drag-race school in central California (see “Dale Walker’s Drag Racing Academy,” Cycle World, May 1988), and I suppose I’d expected some simple, meaty advice like, “Shoot, drop the air pressure in the rear tire and wring that sucker for all she’s worth.” What I got was page after page of quickly scribbled notes as Walker articulately expounded on the finer points of burnouts, staging, launch techniques and powershifting. Drag racing is one of the few forms of motorcycle competition in which I’d never gotten involved, and as I was quickly learning, there is more to it than just lighting the fuse and holding on. Even leaving the line at as low as 4000 rpm, they said, Ed be lucky not to spin the tire. Wheelies wouldn’t be a concern, they assured me. But what they hadn’t counted on was track officials shellacking the first 50 feet of the track with traction compound, a sticky substance that does away with wheelspin almost entirely. Great, I thought, now we’re back to me singing soprano.

It was Walker’s warning about wheelies, though, that had me sweating bullets and sitting cross-legged. “When you launch, try to get as far forward as possible,” he said, “but be careful. The thing will still want to jump up and hit you right in the family jewels.” Wonderful.

Not to worry, the experienced drag racers on staff consoled me, Carlsbad is infamous for its slippery surface.

At least I had plenty of time to ponder my fate. With about 50 cars—mostly muscle machines from the Sixties and Seventies—in line and only four motorcycles, there was at least a half-hour wait between runs. Add in the delays caused by one Chevy-powered Opel’s zero-altitude barrel roll, plus numerous asphalt-litterings by snapped driveshafts and grenaded gearboxes, and five or six runs was all most of us got. Still, for $ 15, that’s not a bad deal for the luxury of being able to wick it up and run flat-out without worrying about a police officer asking for your autograph.

All five of my runs started with a burnout. In drag racing, this is obligatory, like a big-leaguer scratching himself before stepping up to the plate. The experts tell you that a burnout is necessary because it brings the rear tire up to operating temperature and allows for optimum traction. Besides, it gives you a chance to make lots of noise and smoke and impress your girlfriend in the stands. After the smoke would clear, I’d roll up to the start line, where there are two sets of staging lights; break the first beam with the front tire and you’re pre-staged, break the second and you’re staged, waiting for the “christmas tree” above the start line to do its yellow-yellow-greeA? count-down.

For my first run, I lined up at the far right edge of my lane, out of the traction compound. And, sure enough, despite a cautious application of the throttle, the rear tire spun all the way through first gear. Still, I posted a sub-12second elapsed time and beat my opponent, an engineering student riding a 40,000-mile KZ1000. More importantly, I got back in line speaking in the same octave as when I left. For my next two runs, I squared off against a young marine from nearby Camp Pendleton on an FJ 1 100. Both times I lined up on the edge of the traction compound, and although I still spun some, I won both contests and dropped my ET to 11.57 seconds, with a trap speed of 122 miles an hour.

My next time up, I got an insight into the drug-like hold that drag racing has over its participants. With selfless disregard for my ability to father children, I planted myself right in the middle of the traction compound, atop a layer of rubber laid down by the car tires. When the light turned green, I fed in the clutch and the throttle, the Dunlop bit hard but the bike didn't wheelie, and all that was left for me to do was duck out of the windstream and bang shifts at redline. Even as I coasted toward the return road, I knew I’d nailed a good run, and the time slip I was handed validated it: 11.18 seconds at 122.95 miles an hour. Admittedly, my performance didn’t have Dale Walker (who logged a 10.64-second, 128-mph pass on Cycle World's 1985 test V-Max) looking over his shoulder, but I was pumped, hurrying back to the line and hoping to nudge Mr. Max into the 10-second bracket.

But it didn’t happen. I got a good launch on my last run, but over-revved the first two shifts, ending up with an 1 1.33. Another pass or two and I’m sure I could have gotten into the tens. But that’s what is so seductive about the sport: You’re sure that next time, you can leave the line just a little harder, shift just a little more cleanly, tuck in just a little tighter. It’s easy to see how people get inexorably addicted.

Just as with skydiving, my afternoon of drag racing had left me with all my body parts intact. The difference is that when it comes to parachute-driving, for me, once was definitely enough; but withdrag racing, I think I’ll always want just one more shot.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue