Pressing matters

TDC

Kevin Cameron

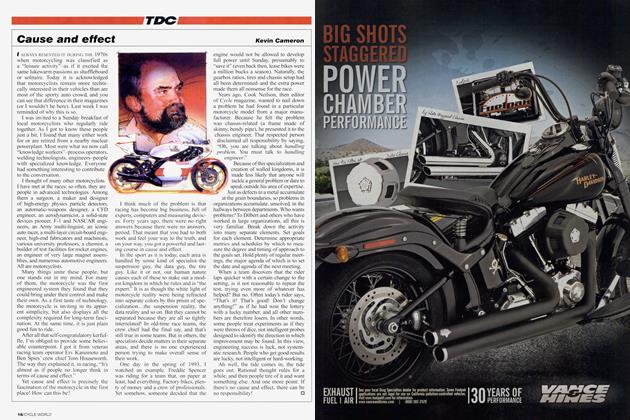

BUILDING PRESSED-TOGETHER CRANK shafts was once a regular part of motorcycling. I found it in the service manual for my AJS 500 Single, and read more in Phil Irving’s classic Tuning for Speed, but had no practical knowledge of the task.

Finally, a trusting person handed me his Montesa crank and a new rod kit consisting of con-rod, crankpin and big-end needle-bearing cage. I found a private place for this first attempt-in a university student machine shop on a summer afternoon. To press out the original crankpin, 1 had to make a support plate that passed between the two flywheels, and somehow get that into the hydraulic press. With only myself watching, I made the classic mistakes and took the first teetery steps toward knowing what I was doing.

After an hour or so, I had the new parts in place, but the two flywheels were both slightly twisted and tilted on the new crankpin, causing the indicator on my dial gauge to whirl and wave. In quiet desperation I had to reason out which alignment problems corresponded to what movements of the dial gauge. Peak readings at 90 degrees to the pin indicated twist, peaks at zero or 180 indicated tilt. Sort of.

Cranks are trued with a soft hammer. Hold the crank in one hand, find the place I’d decided to hit, and strike a measured blow. How hard to hit for an error of .010-inch? Experiment. Little hits changed nothing. I hit harder. Still nothing. Finally, WHAM! Success. I moved it-now the error had jumped to the opposite direction. Back and forth I went, out 10 plus, out 10 minus. I wanted lunch but first, as Sam Cooke said in his song, “I got to work right here.” It was a long afternoon, but finally I had a crank whose two mainshafts were reasonably close to the same centerline. The dial gauge had been calmed.

I was impressed with how much metal deforms around a press-fitted crankpin-turning the crank on V-blocks with the dial gauge touching the outside of a flywheel revealed a big bulge every time the crankpin came past. Today, a rebuild-and-align on a Twin crank retails for more than $250. In 1966, I thought getting $10 for this was easy money, and I did quite a few for a local dealer. The work mostly had to do with being methodical and patient. Sometimes, 1 had to pretend on the patience. And once, assembling a Kawasaki Triple’s crank while talking to a shop visitor, I got out of sequence and had to start all over again. No wonder the crusty old mechanic is a man of few words, even to the point of rudeness.

It would take me many years to admit that I no longer enjoyed this work. How do you discover that TZ750 Yamaha inner flywheels are indexed in matched pairs? You assemble a pair of cranks using the best-looking flywheels you have, only to discover upon completion of the entire engine that you have large and uncorrectable timing differences between cylinders. And how do you fix it? You take the engine all apart, then you take the cranks you have just rebuilt all apart, and you find that the inner pairs have index numbers. Duh. Face becomes red. Anger, embarrassment at self. Rummaging through the “dirty laundry” of assorted flywheels produces same-numbered pairs at last. I do the work over again. Now there are 180 degrees between TDCs on the same crank. Point taken.

Con-rod rollers on 1971 Kaw race cranks broke up in 50-150 miles, while cranks the previous year had run 1000 miles. I found a supplier of German needle rollers in the correct dimensions, enabling us to finish races.

In 1974, Yamaha TZ750A cranks would do 1000 racing miles. As the years passed, we made power at higher revs, and flywheels began to crack or even explode into two big pieces. Big cracks could be detected by eye, and little ones by dye-penetrant. Clean the suspect part with solvent, then wet the crack zone with a dye that wicks its way into any crack. Clean the part again, then spray it with a white chalky powder. Dye from the crack soaks outward into this white layer, tracing the failure in crimson. Kits available at welding-supply stores everywhere. Even smaller cracks required Magnaflux. At any discontinuity in the metal, an imposed magnetic field arcs over the gap through empty space. A magnetic powder is attracted to this escaped field. For every critical aircraft engine part there are instructions on which direction to magnetize the f part and where to look for cracks.

For motorcycle engine parts, you build your own failure history.

In 1965, motorcycle racing was a working-class sport, but 20 years later parts prices had become Gold Coast. People were asking me to piece things together-make one workable crank out of two wiped-out ones. It helped that I’d always saved used-but-usable parts. From having been a rebuilder of racing cranks, with some pretensions of precision, I became a junkman, making 400-mile specials for vintage racers with overhanging mortgage payments. In the beginning, I had ascended with the two-stroke engine on its upward curve of popularity and power. Now I was riding back down as its sun set. Here, this crankpin still has an okay roller track and this big-end roller cage isn’t worn through the plating. These sidewashers have plenty of silver on them. And this flywheel set isn’t cracked, doesn’t have a damaged drivegear keyway, and its crankpin holes aren’t ruined by fretting. Soon, voila! A newly assembled, but nevertheless used crankshaft.

Racing had made the work fun-even at 4 in the morning, in the winter, with the wood stove not quite keeping up. I would warm TZ flywheels by setting them on the stove, and they would warm my hands as I stacked up the parts and pushed them together, then aligned the wheels. But when I stopped living and working at trackside, building cranks became like being on a low-carbohydrate diet and trying to bake bread. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue