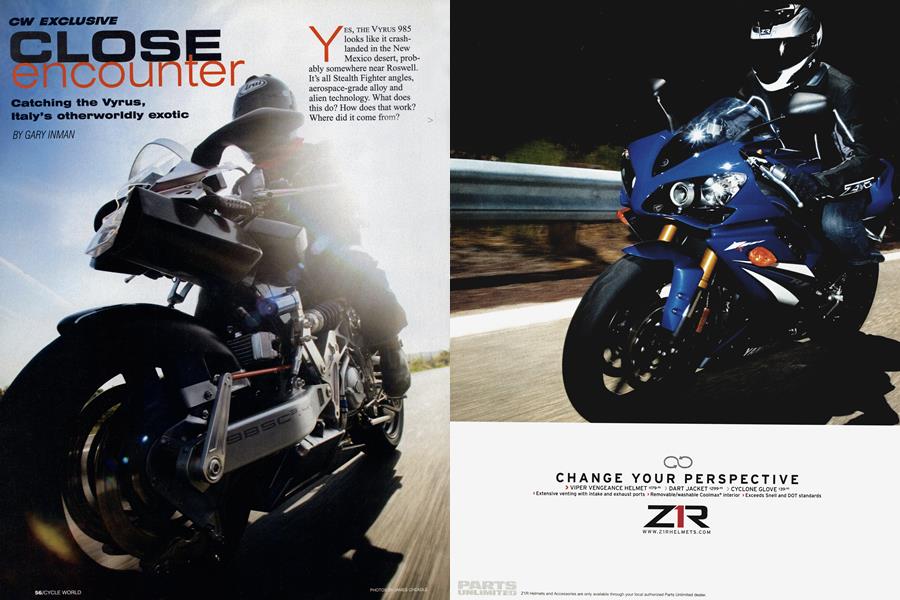

CLOSE encounter

CW EXCLUSIVE

Catching the Vyrus, Italy's otherworldly exotic

GARY INMAN

YES, THE VYRUS 985 looks like it crash-landed in the New Mexico desert, probably somewhere near Roswell. It's all Stealth Fighter angles, aerospace-grade alloy and alien technology. What does this do? How does that work? Where did it come from? But right this minute is not the time to investigate. We've flown in for a day ride on the $85,000 Vyrus ³ 4V, which even if you had the money you can't buy in the States. This range-topper is powered by a sandcast Ducati Testastretta 999R motor; it starts with a slight reluctance as huge showerhead injectors piss fuel down 54mm throttle bodies. Then it clicks and the Zard oval twin exhausts bark a death-metal idle riff. The numbers on the Microtek digital dash dance as I prepare to sling my leg over the most expen sive road bike I've ever been trusted with.

Riding position is on the comfortable side of normal sport bike ergonomics. The flat bars are connected to a feather light top yoke. The yoke can be so minimal because it doesn't clamp fork tops but just acts as something to connect the handlebars to the steering mechanism. Everything up here is radical. The steering-head bearings are sunk straight

into the carbon-fiber airbox-there are no aluminum cups to support them. You've got to be confident with your toleranc es to do that. The bottom of the steering stem is connected to a beautifully 3D-machined tiller that, in turn, is linked by a red steering rod to a triangular cam that pushes and pulls another rod to steer the front wheel. With linkage rods zigzagging forward and backward, it looks like there should be more siop than a galosh top, but the Vyrus feels as natural as skinny-dipping. So good, that within a mile I've forgotten the bike's front end is radically different from anything else I've ridden before. I aim for a few potholes-not hard to find in Northern Italy-and discover the bike doesn't jar. I brake hard and discover it doesn't dive. Then I just enjoy the ride. Soon, all I'm thinking about is the heavy clutch and awesome stomp of the 999R motor. It wheelies like no road bike I've ever ridden. Vyrus says the ³ 4V weighs 346 pounds wet, has a wheelbase of 54.1 inch es and makes 150 horsepower. Top speed has been measured at 181 mph. Radical figures for a radical naked bike.

I'm not the most analytical of riders, not a Princess and Pea-style tester who can tell the difference between five and six turns of preload, but I'm not a complete numptie, either. And the Vyrus is so good to ride, even on Emilio Romagna's polished dusty roads, so beautiful, so danm life affirming just to be next to that the price starts making sense. Almost. I struggle to pick faults. The 2V Vyrus, pow ered by Ducati's air-cooled 1000DS motor, has all the visual impact of the 4V but "only" costs $52,000. I start thinking about what I'd need to liquidate in order to buy one. If I did, I'd never need to buy another bike. Nothing would ever trump it-well, until GSX-Rs start hovering.

The hub-center concept is not new. Englishman Jack DiFazio experimented with it in the Sixties. Elf, Tony Foale, Yamaha and, of course, Bimota with its Tesi, among many others going back to the Neracar of the 1920s, have all had a crack. But Ascanio Rodorigo, 45, the brains, muscle and driving force behind Vyrus, is dismissive of them all, including the early Tesi.

In fact, when the Tesi made its reappearance in 2003, the 2D design had been largely fettled by Rodorigo, and Vyrus built the bikes for Bimota. The two companies have since gone their own ways.

"Our production is handmade and `fit-to-size' (about 30 per year); theirs is industrialized (a few hundred per year), so we had to stop supplying them bikes and now they make their own 3D~' he says.

Though the Vyrus design looks similar to previous Bimotas, every component has been altered. The relationship between the front and rear swingarm-pivot points differs from that of the Tesi and, therefore, so does the frame. The front swingarm is bent in two directions, laterally and tor sionally, and to form the spars, extruded 7020 aluminum is baked overnight at a temperature of 950 degrees Fahrenheit. In the morning it's filled with dry ice (carbon dioxide at minus 110 degrees) and twisted. 7020 aluminum is notori ously hard to work with; it age-hardens, but the complicated and ultra-precise bend Vyrus demands calls for this protracted method.

Internally, the motor remains untouched. Ducati is so happy with how its engines are treated by Vyrus that the Bologna factory offers warranty coverage. No Vyrus cus tomer has ever made a claim. Vyrus fits an Italian Microtek engine-management system, and the loom is Formula Onespec, using 51-pin connectors. Each connector costs $350. There are at least half a dozen of them.

To lighten the whole package and get the road bike to its ultra-low wet weight, the 999R motor has its mechanical water pump replaced by an electric one. Twin radiators made by an Italian F-i supplier are plumbed in using silicone hoses and aluminum tubing. It's incredibly neat. Only the regulator/rectifier sticks out like a sore thumb.

The Zard exhausts are another groundbreaking element of the Vyrus design. Conventional wisdom says a Twin's exhausts have to be of roughly similar measurements to have the same tuned length. This leads to packaging problems. But Vyrus took Ducati's experiments with variable lengths and diameters to extremes. The pipe from the front cylinder is 78.7 inches front-to-back, the rear is just 23.6.

Rodorigo is a man obsessed with quality and weight. Even the bike's fasteners are specially made. "You cannot put pro duction bolts on a bike like this," he says. Each Allen bolt's head is tapered. Only one bracket on the whole bike has not been machined from solid, and that's the one that holds the sidestand. Even the connectors that feed coolant into the cylinders' water jackets are machined from solid. The $85-grand price tag isn't plucked out of thin air. Attention to detail like this doesn't come cheaply.

When it comes to weight, the frame is as minimal as it gets. The airbox and bar support is 1 .5mm-thick carbon fiber formed in an autoclave. Wheels are forged PVMs.

Despite all this, the Vyrus is fully homologated throughout Europe and passes Euro 3 emissions-although it must be pointed out that the 4V doesn't make it through the test with the optional Zard pipes fitted to my bike. And every Vyrus comes with a three-year warranty. Radical had never been this sensible.

When I was 10, I drew motorcycles all the time," Rodorigo says. "Later, I would go to school every day with black hands from working on motorcycles. After school I would stand outside the door of the workshop of Dervis Macrelli (the father-son outfit com missioned to make prototypes of all the Bimotas and even the Ducati 916). I'd stand there and see what I could learn. One day the father was ill and Dervis was struggling, so he said `Ascanio, come in here and help."

Rodorigo worked for Macrelli full-time before join ing Bimota, where he fell in love with Marconi's Tesi. He left Bimota after two years to set up ARP, a company that built specials. This business continued until an old friend, race engineer Matthew Casey, encouraged him to improve the Tesi concept. The result was the first Vyrus. It was unveiled at the Milan Show in 2002. The reception the oneoff received encouraged him to mothball ARP and launch Vyrus. Since then he's sold 98 bikes-that breaks down as 82 of the 984 2Vs and 16 of the 985 4Vs.

T he entire Vyrus workforce-six people-is housed in a factory just off the SS16. It's actually more of a workshop on the southern outskirts of Rimini. Small, with residential flats above. Tiled floor, nuts and washers in orderly lines. Past the assembly area and hidden by screens is a tidy machining section with lathe, mill and welders. Turn left and there is Rodorigo's own private workshop where prototypes are worked on. He has one of the most inquiring minds in modern motorcy cling. His Scientologist background (the religion favored by roadrace guru Keith Code and 4V customer Tom Cruise) seems to allow him to strip long-held motorcycling rules back to the bare minimum and reinvent them. This window less corner of the workshop is where the ideas crawl from

the drawing board and into life. But the parts ware house is the most impres sive area of Vyrus HQ. Machined aluminum turns me on, and so this room is heaven. As noted, virtually every component is made by Vyrus in limited batches, everything but wheels, engines, electrical components and suspension units. In the stores sit tubs and parts bins full ofjewel like components, enough to build a number of bikes. An almost incomprehensible investment for an operation of this size. But it works because the whole structure of the company, according to Rodorigo, has been deconstructed and re-engineered. He tries to explain, and while it is fascinating, I can't pretend to understand it all. What I do like is the fact that even the most skilled engineer is still expected to clean the toilets once a week. All for one and one for all at Vyrus.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue