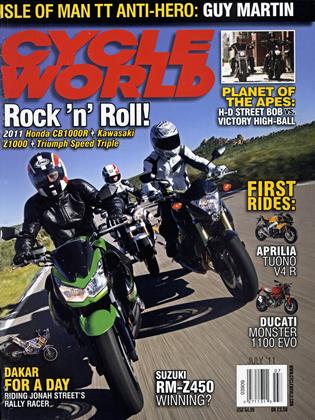

TT Anti-Hero

RACE WATCH

The rise and rise of Guy Martin

GARY INMAN

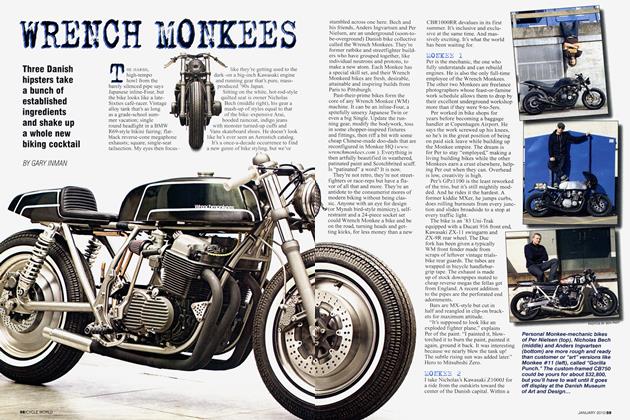

"I’D JUST LIKE TO APOLOGIZE TO THE TT organization and all our sponsors about the failure of our rider to attend this event,” says a sheepish Philip Neill, boss of the factory-supported Relentless Suzuki by TAS Racing team. The event is the April press launch of the 2011 Isle of Man TT races. The rider is Guy Martin.

Every other key name is here. Riders have flown in from Australia, New Zealand, France and the United States. Martin is on The Island, but no one at the launch knows where. People are annoyed by his absence but only mildly surprised.

Fifteen-time TT winner John McGuinness is here to be introduced to the world’s press. Fie finished fifth in the Bol d’Or 24-hour endurance race in France a little more than a day ago. Here, too, is record-breaking five-TT-wins in-a-week Ian Hutchinson, despite the fact his shattered leg is surrounded by a cage that would hold a lion. With all due respect-and I respect TT racers more than any other sports peopleit's Guy Martin, without a single TT win to his name, who is the most-popular and in-demand man in 21 st-century "real road" racing. And if he doesn't want to turn up, no matter how much sponsor pressure is put on him, he doesn't. It's disrespectful, brattish, rude, exasperating.

Sometimes, though, Martin's behavior makes me laugh. Here's a rider not willing to toe any one's party line, and hitting him in his pocketwhere it seems to hurt riders most-doesn't make any difference.

I've known about Martin for six years and spoken with him on a regular basis for the last four. In that time, he’s gone from a promising short-circuit privateer to the most famous motorcyclist in Britain. A TT racer hasn’t been a household name in the U.K. since Mike Hailwood’s era, but Guy Martin is just that.

In the last couple of years, Martin has become the star of the much-anticipated feature-length documentary, TT 3D: Closer To The Edge, on-screen presenter of “The Boat That Guy Built,” a six-part primetime BBC1 series on the Industrial Revolution, and a brand ambassador for AGV and Dainese. In the global marketing nerve center of the Italian apparel-maker’s Vicenza HQ, where the opinion-formers are free to surround themselves with what they dig right now, a poster of the Englishman dwarfs that of Valentino Rossi.

Guy Martin might be a team manager’s nightmare, but he’s a journalist’s dream. He tells the truth, as he sees it,

in that instant, to whomever is listening. Fans love his call-a-spade-a-spade honesty, but it drives manufacturers, bosses and race organizers wild. When their patience runs out, there is always another willing to sign up Martin.

“If I kill myself, so what?” he says. “My girlfriend might miss me, my mum might miss me, but screw it. If I worried about ‘ifs’ all the time, I wouldn’t get out of bed.”

Martin laid out this view on life-anddeath halfway through my first big interview with him back in early 2006. A few years later, I’m positive he still believes it. It’s not a death wish. It’s the opposite: He’s found something he loves so much that a life without road racing is barely worth living. Ask him why he races and the reply is always the same: “Where else can I get this kind of buzz?” He respects riders who walk away from road racing, but he’s not ready to leave it yet. “I’m not going to the grave ’til I win a TT,” he says. “No way.”

Motorcycle race fans have built-in B.S. detectors, and riders who don’t walk it like they talk it aren’t tolerated for long. Martin certainly walks the walk. Sure, he may not have won a TT, but don’t think he’s an also-ran. He’s set lap records, stood on the podium nine times and won other major “mass-start” road races. You think the TT is crazy? You should see a dozen top riders tunneling into the first turn of the Ulster GP or freight-training down the 200-mph straights at the Northwest 200 in Ireland.

Martin was leading the Senior TT last year when he crashed, his Honda CBR1000RR exploding spectacularly, causing the race to be red-flagged for the first time in its history. He broke three vertebrae, a few ribs and singed his eyebrows. He was racing on the roads again—and scoring podiums— before the end of the same season.

So much opinion surrounds Martin that it’s sometimes easy to forget what a talent he is. The level at which he and other top TT riders operate was reiterated when he described last year’s crash.

Martin lost the front end through 170-mph Ballagarey Corner. There’s next to nowhere you’d want to crash on the TT course, but if there’s one corner you really don’t want to go badly, it’s Ballagarey. TT regulars have long referred to it as “Ballascary,” and it had already claimed one racer’s life that week—Kiwi Paul Dobbs. But, when most humans, even most top-level motorcycle racers, would be watching their lives flashing before their eyes, Martin was working on a plan. A plan that ultimately saved his life.

“I thought, ‘I’ve got it, I’ve got it, I’ve got it, I’ve got it,”’ he explains. “You sometimes get away with front-end tucks. You save them on your knee or give it a bit of throttle or a bit of back brake and it’ll come back to you. You don’t do anything major and you don’t panic because that’s when you come off. I went through all that process and thought ‘game over.’”

Martin made this series of tiny adjustments, processing the feedback and thinking of the next thing to try as he was heading for a dry-stone wall, just a few yards from the apex of Ballagarey, at 170 mph. That was the point when he realized there was no saving this one. He slid down the road, hit a wall, bounced over the other side of the road and hit another wall. He was knocked out by the time his bike exploded, engulfing him in a 25-foot-tall fireball.

“I didn’t think, ‘This is going to hurt,’ just, ‘Whatever will be, will be,”’ he says.

Feeling the tire lose traction the instant it did and trying to correct the slide is what saved Martin’s skin. He held onto the bike long enough to ensure his trajectory was down the road,

so he hit the walls at a glancing angle, not head-on.

This Englishman lives by the Irish phrase, “We’re not here for a long time, we’re here for a good time.” He’s not the only roads man to use this motto as a guide to life. It’s said one current star used to book a one-way ferry ticket to The Island in case he didn’t need the return. It’s morbid bravado: “Don’t get in my way; I don’t even care if I get out of here alive.” Of course, they do care. Most of them, anyway.

Until recently, Martin lived with his former girlfriend and her parents. Now, he’s lodging with a friend. When he travels to races, he does so in a small van, and he often sleeps in the back of it. Yet he bought an Aston-Martin V12 Vantage, a $ 180,000 automobile, on a whim. He’s barely driven it. He’s more excited about his turbocharged Suzuki GSX-R1100 streetfighter. He’s clearly not planning for the future.

For years, Martin worked in the family firm servicing 18-wheeler trucks and harvested on local farms in the evening. Now, he’s laboring on building sites, laying concrete, demolishing walls, fixing roofs—whatever’s required. He cycles to work and back. In the evenings, he tunes engines and skims heads for local garages. “I used to sit on the bench when I was in nappies watching my dad build Triumph engines,” he says. “I was mesmerized.” He’s proud that he’s hardly ever seen the inside of a gym. “I need to work to keep motorcycle racing feeling special. I don’t want it to feel like a job.”

Things happen to, for and around Guy Martin mainly because he lives three men’s lives every week. He’s in perpetual motion. He doesn’t have a manager, mostly because he’s as unmanageable as his hedgerow hair and trademark Wolverine sideburns.

Public-road racing has never been short of characters, and the current crop is a lovable freakshow compared to the sponsor-loving, polished athletes on the world scene. But, despite being the son of an amateur TT racer, Martin isn’t a born-and-bred real roads man like, say, Robert Dunlop’s youngest son, Michael. Martin only took to the roads after being banned by the U.K. racing’s governing body, the ACU.

Back in 2002, Martin had a second place in a British National Junior Supersport race taken away from him after he cut a chicane. He lost time, rather than gaining it, but was still docked 10 seconds. He went to complain and ended up slamming a laptop on the race secretary’s fingers. That action seems out of character now, even though he boycotted the podium at last year’s TT after disagreeing about the severity of a 30-second penalty for being 0.08 mph over the pit-lane speed limit.

It’s out of character because Martin is a lover of life. He loves experiences. He admits he’s not the sharpest knife in the drawer, but he craves nuggets of information and is as happy talking to lords as laborers. One thing he’s beginning to hate is the attention that just being himself has brought. Because he has always been so approachable, he’s constantly approached, often when he’s getting in the frame of mind to take on the most dangerous challenges in professional sport.

“He’s changed,” some sneer. Really, the biggest change is the fact that it’s not 10 well-wishers wanting to shake Martin’s hand but a thousand. During TT fortnight, he’s a hunted man and goes underground, avoiding the pits as much as he can.

Later the same day of the TT press conference no-show, I sit at a table with Martin and the father-and-son Relentless Suzuki team boss and owner pairing, Philip and Hector Neill. They’re laughing and joking like nothing happened. There’s a pint of Guinness in front of the rider as he shovels curry and rice down his neck. Guy Martin is so lovable and charming that it takes a lot of letdowns, crossed wires and missed appointments for people around him to cry “Enough!” But people eventually do. If the multi-national sponsorship dried up tomorrow, I doubt Martin would lose a minute’s sleep. He’d dig deep, sell the sports car that he never drives, buy his own bikes and go racing. In fact, I think he’d probably prefer it that way.

The lid will blow off The Island if Guy Martin scores his maiden TT win this year. And it is a big “if.” He’s missed out by fewer than 3 seconds in a four-lap race that lasts 72 minutes with 127-mph-plus average lap times on a 600. Average lap times! The concentration is mind-boggling. But if he never wins a TT or bags 15,1 won’t alter my opinion of him. Guy Martin is one of best things to happen to British bike racing in the last 30 years, and that won’t change whether he finishes 3 seconds in front or behind someone else. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Mysteries of Grandpa

JULY 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

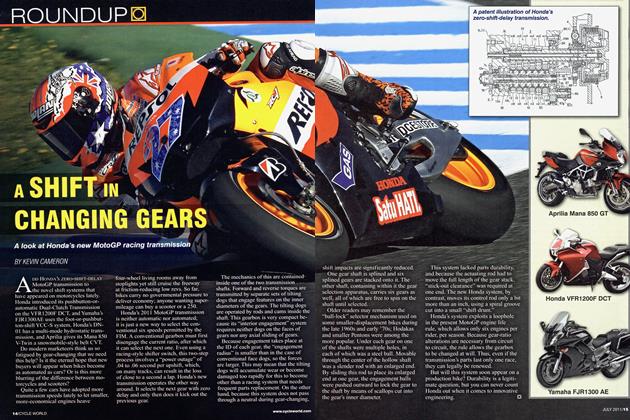

Roundup

RoundupA Shift In Changing Gears

JULY 2011 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupBmw S600rr

JULY 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

Roundup“chrome” Hawk

JULY 2011 By John Burns -

Roundup

RoundupCycleworld.Com Poll Results

JULY 2011 -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago July 1986

JULY 2011 By Blake Conner