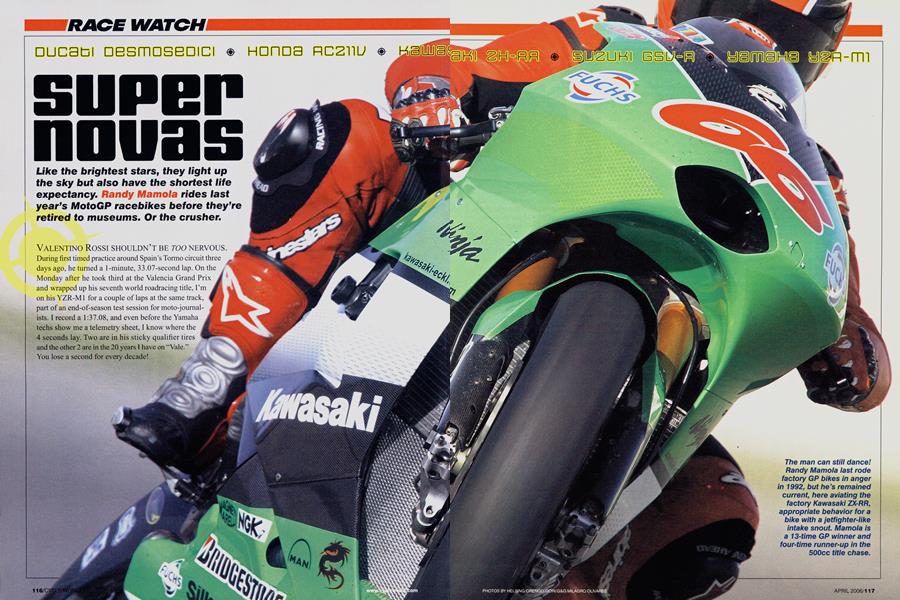

SUPER novas

RACE WATCH

Ducati Desmoseoici Hono Rc211v Kawa aki ZH-RR SUZUKI GSV-Yamaha y2R-m1

Like the brightest stars, they light up the sky but also have the shortest life expectancy1 Randy Mamola rides last year's MotoGP racebikes before they're retired to museums. Or the crusher.

VALENTINO Rossi SHOULDN'T BE TOO NERVOUS. During first timed practice around Spain's Tormo circuit three days ago, he turned a 1-minute, 33.07-second lap. On the Monday after he took third at the Valencia Grand Prix and wrapped up his seventh world roadracing title, I'm on his YZR-M1 for a couple of laps at the same track, part of an end-of-season test session for moto-journal ists. 1 record a 1:37.08, and even before the Yamaha tcchs show me a teknietrv sheet, I know where the 4 seconds lay. Two are in his sticky qualifier tires and the other 2 are in the 20 years I have on Vale." You lose a second for every' decade!

I retired from Grand Prix racing in 1992 but have never been very far away from the paddock, closely following the evolution of the two-stroke 500s as well as the arrival and development of the 990cc MotoGP four-strokes. Time spent as a test consultant, trackside commentator, BMW BoxerCup racer and pilot of the two-seat Ducati GP demonstration bike has kept my 46-year-old body and mind in fairly race-ready shape-at least for a few laps at a whack.

Seat time at these joumo gang-rides is short, and while I get on the bikes smiling, once the visor goes down it’s all business. On my out-lap, I try to get a general feeling for the machine and get my track references down in order to be able to give it a real go on the next two laps. To really see how these bikes behave, you have to get down into lap times that are close to race pace. Not easy, as each bike feels and acts differently; you have to be a real chameleon to adapt quickly.

T he main problem for the manufac turers when faced with the task of designing their first MotoGP motorcy cles for 2002 was that they had no real references. It was a completely new class, and initially, each brand had to pretty much go out on a limb with a to tally unproven design concept. Only Honda with its V-Five hit the nail square during that first year. They had the bike, they had the team. . . and, of course, they had Valentino Rossi. rL~

The first season Rossi rode the Honda RC2 liv, he was on the best bike by a long shot. Crew chief Jerry Burgess remem bers, "In 2002, we only took advantage of 40 percent of the Honda's possibilities; we still had 60 percent left in reserve. It was incredible. And we didn't need to do any thing, because the other bikes were like streetbikes-they looked like they were go ing fast but really were not." Yamaha, certainly, struggled a great deal in those first years of four-stroke GP. I remember testing the Ml in `03, and it was a complicated, confounding motorcycle. The gas tank actually came up and smacked my chin bar several times as the engine's erratic power came in and made the whole bike unstable. It was violent and unpredictable. I imagine the first time Rossi tried the Yamaha af ter jumping camp he must have wanted to cry-though his tears probably didn't last too long because along came Yama ha and Burgess with a crate of different engines to try. More importantly, riders now have help from computers. If you think back to those first years, you will remember how all the bikes moved around on the brakes and how uncontrolled the corner-exit slides looked compared to now. Evolution of the species has eliminated everything in the bikes' behavior that is not forward motion; now they hardly move around and are much more stable and controllable.

Thank the black boxes, much-refined and now an indispensable part of motor cycle racing's premier class. Yes, you need a good mechanical base, but it's electron ics that make the difference. Tuning rider aids such as tractionand wheelie control has become one of the main ar eas of work for teams.

A perfect example of the importance of power delivery can be found in the Yamaha’s evolution. In 2004, they softened up the M1 but were short on power compared to the Honda and Ducati. The problem was that when horsepower was increased, they ran into problems with the rear end stepping out, which in turn accelerated tire wear. The team tried many different suspension settings, but it wasn’t until they refined the power curve and optimized traction-control that the sliding went away.

With 250 horsepower on tap, control is the key, especially during a full race, where consistency and tire wear are allimportant. You need a flat torque curve, not nervous, two-stroke-style power. Whatever the fusion of latest technologies may be to arrive at this point, it’s clear to me after riding these bikes that this is the main difference between a machine that is capable of winning races and one that is not. CPUs rule.

This season, the Italians made a risky bet going from Michelin to Bridgestone. At the beginning of the year, it looked like they might have made a mistake, but in the latter part of the season, the tires evolved to suit the big Ducati. Being the development leaders for Bridgestone definitely has its advantages.

From the start, Ducati’s MotoGP project has been loyal to the brand’s philosophy of cutting its own path in a different direction from the Japanese. The Desmosedici V-Four has the shortest stroke among all of the four-cylinder bikes, with a bore of about 88mm, allowing higher rev capabilities. Its cylinders are 90 degrees apart, the widest angle currently raced, forcing the “D 16” to be the longest. But it’s also the smoothest, with no need for vibration control.

Another big difference is Bologna’s desmodromic valvetrain. It’s efficient and a company signature but does have some limitations at high revs, and it is unknown how many rpm it will permit. This will be a decisive factor in 2007 when new equipment rules drop displacement and move redlines up.

In the chassis department, the Desmosedici is also unique. The engine forms an integral part of the frame instead of just hanging from it, uniting the trellis steel upper frame to the swingarm and rear suspension.

Ducati has worked with Marelli electronics and fuel-injection from the beginning. One of the D16’s main problems has been fuel consumption, and during the year, an innovative way to save the fuel wasted under braking was tested. The system works by disengaging the engine from the rear wheel as if going into neutral with the engine at idle. It senses brake-lever pressure to engage and disengage, adjusting engine rpm to match rear-wheel speed before it disengages. The system was hard for the riders to adapt to, however, and still needs to evolve.

In 2004, Ducati changed the engine's firing to what they called a "Twin Pulse" configuration that basically turned the V Four into a big V-Twin with each pair of cylinders firing at once. But it wasn't until the arrival of the latest Bridgestones that Ducati moved to the front The tires are radically different, with taller and wider construc` tion than before. Bottom line: increased contact patch, more gnp and more durability

bucati works with Ohlins suspension but uses compo nents that have already been developed, nothing radical. In addition to working with sus pension settings, the Ducati tech nicians adjust frame flex with different configurations and rein forcements in the trellis frame sec tions. In a blow for manual tuning, these can be bolted in or out to change chassis rigidity, no CPU required!

HRC completely restructured its Mo toGP racing division after 2004's dis astrous results (remember the "We don't need Rossi" comments?), and the RC211V was changed considerably for `05.

This latest version of the Honda has a smaller and more powerftil engine that spins an extra 1000 rpm. Figure an 83 x 37mm bore/stroke combination. Engine architecture remains unchanged, with the four outer cylinders set at 360 degrees and the fifth center piston working at a slightly different angle. Under this con figuration, the front and rear outer cylin ders share the same exhaust while the middle cylinder has its own. Honda con tinues to have the most-powerful and best-accelerating engine on the grid with out any weight handicap from their fifth cylinder. A

Honda is the only manufacturer j that uses conventional throttle control, as opposed to the "fly-by-wire" solutions adopted by Ducati, Suzuki, Kawasaki and Yamaha. In the first three gears, a me chanical system physically limits throt tle opening. So HRC's electronic traction control acts upon the fuel and ignition curves but not -throttle position as do the others' 100 percent electronically managed systems.

During the 2005 season, the focus was on increasing the power~, and the side ef fects were some very un-Hondalike engine failures As agy4~ result, at some races redline was re duced slightly for safety. Even so, fail ures like the one that Sete Gibernau ex perienced during the first laps of the race at Valencia show that the RC21 1V is now working at its limit. Sand forces it to be placed high in the frame to achieve necessary cornering clearance.

The main chassis has not changed much, although swingarm-pivot points and different shock-linkage systems were areas that the HRC guys played around with to increase rear grip. The steeringhead angle was also varied to improve agility. So many geometry variations are uncommon for Honda; historically, their GP bikes are the ones with the fewest chassis adjustments. This season, I would not expect to see very many changes; it's almost like they started working on `06 halfway through the `05 season. -

r Last year, only three riders worked with full-factory HRC bikes: Repsol men Nicky Hayden and Max Biaggi, and Movistar's Gibernau. The rest of the Honda field was aboard 2004 models that re ceived updates during the season. Interestingly, these `04 bikes are the ones that collected most of the Honda victories.

Afl fter Kawasaki's mid-pack 2004 season, both the team and the riders knew what they needed from the ZX RR: a "Big Bang" engine. They watched closely as MotoGP's other inline-Four, the Yamaha Ml, went from a violent "screamer" to a bike capable of win ning world championships. No more research was needed. - -. Kawasaki did an un characteristic thing for a Japanese company in hiring ex-Yamaha engineer Ichiro Yoda, who helped turntheRR into a Banger.

The Kawasaki engine is quite conven tional in design. It's high-revving, with a short stroke and big bore (maybe 86mm), which makes the engine relatively wide

To change the firing sequence, Kawasaki went from 180-degree crankpin positions to ones between 130 and 150 degrees, achieving the irregular sequence that favors traction and control over maximum power. The new firing order required a different exhaust system, and the team tested many configurations before deciding to use individual pipes with no mufflers that end at the back of the fairing. This option gave the Kawi more midrange power but less top end.

One problem brought on by the new configuration was increased vibration. There is no counterbalancer. The original 180-degree engine design didn’t need it, and adding one would have required completely new cases. This will be coming in ’06, bringing the ZX-RR that much closer to the Yamaha in design layout.

Besides the engine, the team focused on electronics and the bike’s slipper clutch. Apparent even on the TV screen, the ZXRR still is not the smoothest bike out there, but Kawasaki’s tractionand wheelie-control now alters fuel-injection as well as ignition, helping to smooth out power delivery.

The chassis is virtually the same as before, but the swingarm has been redesigned to increase rigidity without changing its measurements. The only other significant change has been fitment of the new-generation Bridgestones, although Kawasaki did not experience the same immediate benefits as Ducati.

S uzuki started the new era of Grand Prix racing with an engine configuration it had no experience with. It's the only Japanese V-Four in MotoGP and is built to very compact specifications. It has the smallest angle among the Vee configurations, coming in at 65 degrees, and because of this it is also the shortest of the Vees back-to-front.

The problem is that some of the com ponents are a bit crowded, especially around the intake area. With such a small cylin der angle, the Suzuki is also far from the perfect primary balance point of a 90degree motor, so it requires a balance shaft to keep the vibes down. The GSV-R has the longest stroke of all the bikes, between 82 and 83mm, and its pistons are about 5mm smaller in diameter than those of the Ducati.

Suzuki originally designed a motorcy cle that relied heavily on electronics to keep it under control. Too heavily. As I mentioned previously, the better and more refined an engine is to start with, the less input you need from the CPU and the more you can be in control of the rear wheel Suzuki's problem was that the bike was "over-controlled" by its on board computers Dial on the gas, you get no reaction at first, so you ask for more throttle and then it comes on all at once1

Since then, the engine has evolved and become more rider-friendly, but the team's challenge for 2006 will be to move the bike much more in that direction.

The GSV-R's crankpins are set at 360 degrees, even though the counterbalancer would have allowed for different align ments. The firing configuration is not quite as radical as the Ducati Twin Pulse. Instead of firing two cylinders at once followed by the next two 90 degrees lat er, the Suzuki fires two with a separation of 65 degrees and the other two with the same separation one revolution later. This system allows for two separate 2-into-i exhausts that exit under the engine.

Because the engine is very narrow, the Suzuki can get away with using a fairly conventional chassis. It wraps around the engine, and the rear shock is directly at tached to it as opposed to being bolted to the engine. In spite of the fact that Su zuki engineers made the chassis and swin garm more rigid, like their counterparts at Kawasaki, they do not seem to have obtained the same benefits from the ar rival of the new Bridgestones as has Ducati. Will the Japanese teams get more attention in 2006?

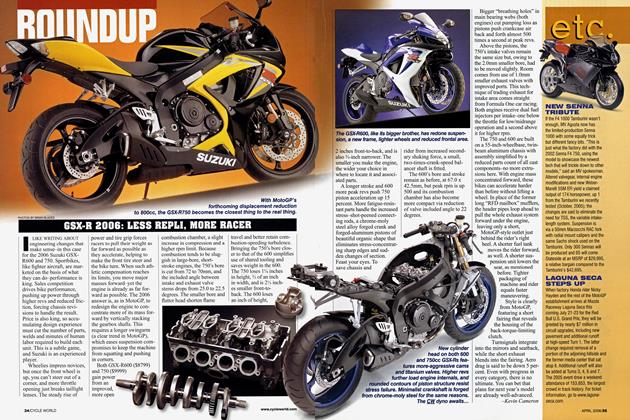

P leasantly surprised by Rossi's world championship first year out, Yamaha redoubled its efforts and built a com pletely new bike for 2005. It is better in all areas than previous versions, with more power and a better delivery. The development team of engineers led by Masahiko Nakajima got more power by reducing stroke and raising the engine's redline to over 17,000 rpm. In doing so, they increased cylinder bore to about 85mm, which made the cylinder block wider. In order to maintain the same overall engine width, they were forced to move the camdrive gears from the side of the engine and hide them behind the cylinders. Now the gears only act on the intake cam and it, in turn, activates the exhaust cam.

Since "The Doctor's" arrival, the (~ Ml `s crank has also received heavy modification, although it continues to rotate "backwards." Its pins are now set at 180 degrees, with the outer cylin ders firing at the same time and the center two 180 degrees later. This way there is a 540-degree break before the outer two fire again, allowing the bike to get better traction.

With this firing sequence, the Ml can continue to use a conventional 4-2-1 ex haust with a muffler and achieve good top-end power. Marelli is in charge of Yamaha's electronics, which include trac tion, anti-wheelie and engine-braking controls. To efficiently and precisely con trol the engine, the Marelli CPU analyzes information from many sensors located in the engine, suspension, wheels and rid er controls, and adjusts the ignition and injection curves as well as actually oper ating the injector throttle bodies.

The new engine is shorter, with verti cally stacked gearshafts allowing the swingarm to be longer and achieve better anti-squat characteristics without affect ing overall wheelbase.

The smaller engine, along with the

newly designed fuel tank, has helped con centrate mass. These improvements have been complemented with a more rigid chassis that is shorter and has a reinforced steering head as well as lateral reinforce ments. The shock mount has disappeared from the chassis and now directly attach es to the back of the engine.

Yamaha leads Ohlins' development program in MotoGP, and they have in Valentino an ideal test rider. Likewise, the team gets all the attention of the Miche un tire techs. Anything else, Mr. Rossi?

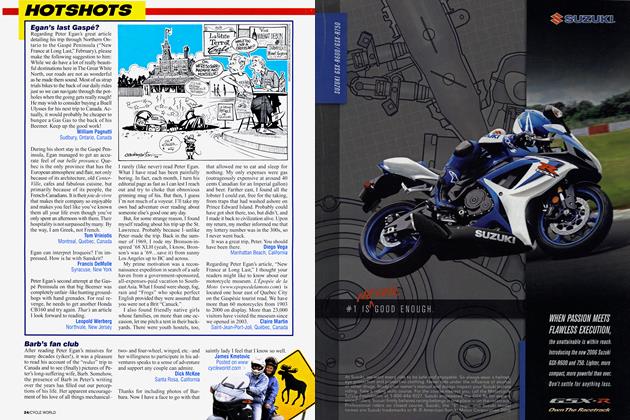

There is a clear division that sepa rates the MotoGP field, with Yama ha, Honda and Ducati one or two steps ahead of Suzuki, Team Roberts (now with Honda V-Five power for 2006, the less said about the Roberts-KTM "disagree ment" the better) and Kawasaki-although the green bike is quickly closing in on the lead group.

This doesn't mean that it's impossible to go fast on the Suzuki, but it is defi nitely not as easy, and it would be very difficult to be consistent during a race. The engine is the main difference, but the whole balance of the top bikes is bet ter. Take riding position, for instance: The Suzuki just felt wrong, with a short tank that places you too close to the handle bars, and footpegs that are too far back. It was like I was an Olympic runner bent down at the starting line with my feet in the blocks. I had to brace myself hard under braking and lock my elbows, mak ing corner entrances awkward. A good test rider back in Japan would have solved these problems before the season started.

The Big Bang configuration was defi nitely the way to go for Kawasaki. The ZX-RR is a much better motorcycle this year, even if it is still a little rough around the edges. It feels the same way it sounds, Grrrrrr!, with more vibration than the rest. Kinda like holding onto an old alarm clock, but it is much more effective on corner exits than it used to be.

Riding the Ducati two-seater at all of the GPs meant I was at home on Loris Capirossi's Desmosedici as soon as I left pit row-a good thing, as the gearbox start ed acting up, and I only got one lap at speed. I immediately noticed a big im provement from the 2004 model. The `05 version is much easier to ride, with smooth er power delivery and a lighter feel, al though it's still not as agile as the Kawa saki or Yamaha. The Desmosedici's en gine is still strong off the bottom with good power and traction, though com pared to the optimized Yamaha, you need to have more throttle control to keep it from spinning up.

The Honda felt very similar off the bottom. It's important to mention here that Honda did its GP press tests two weeks after everybody else, at the Sepang circuit in Malaysia, which is a very different track than Valencia. Nevertheless, it's clear the RC211V is more powerftil down low than its predecessor. It is easy to control but wanted to slide out of corners and, as with the Ducati, I had to be careful with the throttle.

Even with this stronger power deliv ery, the Honda is still the easiest motor cycle to ride out `of these five because even with the slides, you still have a lot of drive accelerating out of the corners and are not forced to carry so much corner speed. The Yamaha has less of a tendency to step out, but you need to carry higher corner speed because you don't have quite as much acceleration to get you

moving again if you lose momentum.

IHuvfl1~, a~~tii 11 yvu iu~c 111V111~11Luui. For more experienced and talented riders, though, the Yamaha is a sure win ner. It surprised me that the same overall easy character that the bike had last year has been maintained but now with added power. The engine feels electric, soft even, with its muffled exhaust (the only bike out there that lets you hear your own thoughts). The Ml just invites you to give it more gas and to push it a little harder. With Rossi aboard, it's almost an unfair advantage.

A n the Yamaha, it is hard to tell when the traction-control is working. It's so good and in tune with the power de livery that you just forget about it, but it's not magic that lets you control the bike so smoothly, it's the CPU.

On the Kawasaki, sometimes it seems like the computer's bells and whistles are working against you because you can feel so much electronic "interference." It's distracting the way it cuts out if the rear slides or the front comes up a bit:

On the three "A Group" bikes, the electronics work almost invisibly. Good traction control does not stop a slide, it just smoothes it out and allows you to have a more controlled feel when the rear breaks away. You also don't lose as much time when the bike slides because instead of spinning up and slewing side ways, rear wheel speed doesn't go off the scale-it keeps driving you forward. As Burgess told me, "To get a com petitive engine in MotoGP, you need to work hard on the electronics. Your work has to be transparent so that it doesn't in terfere with the rider but instead is work ing in the background to help him."

The Honda's semi-electronic traction control works this way also, allowing controllable and predictable slides. But the evolution in power of the rest of the MotoGP field has forced Honda to ex tract more horses out of their RC-V en gine, giving the bike a stronger response down low than before. The Honda has the best acceleration of any bike out there and allows for a real stop-and-go style. The downside is the motorcycle feels heavier and not as agile as the Yamaha, and it still moves around too much on the brakes.

B raking is another area in which elec tronics help these bikes, along with highly tuned slipper-clutch mechanisms, though some work better than others. When you gear down to first on the Su zuki, the rear wheel moves around and loses grip, while on the Ducati and the Yamaha, you just feel like someone is pulling you backward-no matter what you do, the rear wheel stays planted and helps you brake. It's like both wheels are working under you instead of having all of the weight on the front.

The Kawi is real close to these two, but, once again, it feels very mechanical and rough.

And where does the Honda place in engine braking? Last! You read that right, the Honda is the worst on the brakes. Click down through the gears too fast, the Honda will lock the rear wheel for a moment and then you feel some chatter as the electronics fight the engine brak ing. With the Marelli systems of Yamaha and Ducati, you feel nothing except smooth braking.

I n general, all of the new-generation MotoGP bikes feel lighter and quicker. Every year, they are growing closer to 250s and farther away from Superbikes, and in 2007 when the new 800cc rules come into play, we will really see how agile big 200-plus-hp four-strokes can be. If! had to pick a bike to race, it would definitely be the Yamaha because it is the most balanced and rider-friendly. Part of being a great rider is knowing how to optimize your equipment, and Rossi didn't just get on the Ml, close his eyes and give it a big handful to win his back-to-back titles. He raised the Ml to a higher level that allowed him to be competitive. And no matter how much the new-age electronics smooth things out, as Valentino says, "It's still the rider who takes it to the limit."