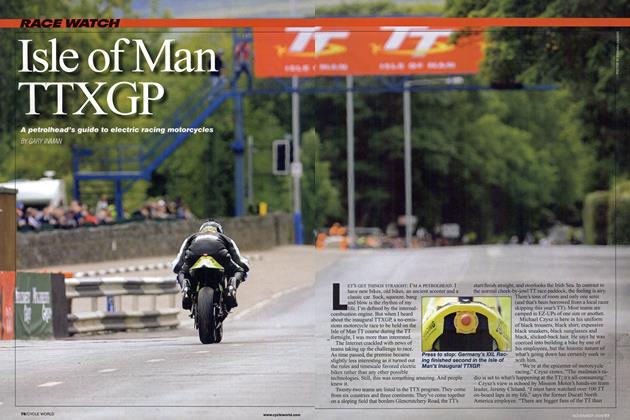

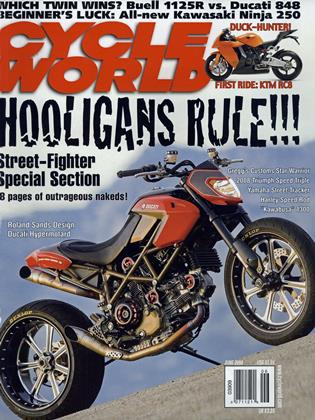

FREEDOM FIGHTER

SPECIAL SECTION STREET FIGHTERS

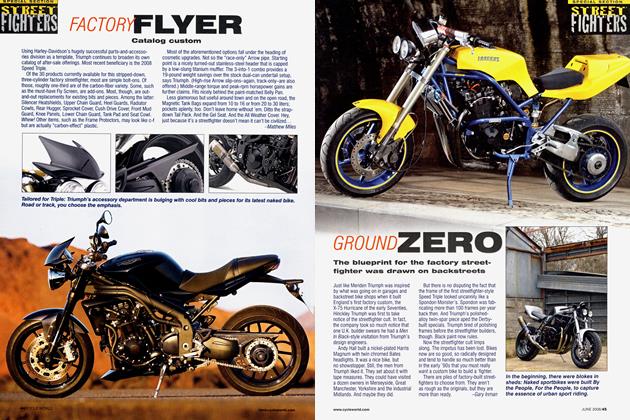

Triumph's stripped-down sportbike came from the street

GARY INMAN

EVER FOUND YOURSELF EXPERIENCING AN OUT-OFbody moment, where all hindsight is removed, and you look down and think, "I never saw that coming"?

It’s what I’m feeling right now. I’m sitting in the small conference room of a hotel that is pretending to be a hollowed-out volcano listening to one of Triumph’s sales team describe the soon-to-be released, revamped Speed Triple 1050.

That’s not too unusual. What metaphorically pokes me in the eye is when Triumph’s representative proudly labels his company’s latest incarnation of the Speed Triple a “streetfighter.” I can’t help but smile. Thirteen years ago, my first full-time journalism job was on the cult British magazine, Streetfighters. Back then it never occurred to me, or anyone else involved with the scene, that a serious global player would even acknowledge this minority cult, never mind actually admit they built one.

The very idea was preposterous. We were on the most extreme fringes of Northern European motorcycling making a nuisance of ourselves. We even made a sticker that wallowed in all the negative connotations of the one-off specials we built, rode and wrote about: “It’s bikes like this that’ll spoil motorcycling for everyone.”

These bikes were two-wheeled hot-rods in the very purest sense. Stripped down and tuned up. Noisy, aggressive, antieverything except fun and speed. Just the ingredients that have drawn men onto two wheels for 100 years.

The origins of the species are disputed. Some say the Germans put high-bar conversions on sportbikes to lessen the soft tissue damage of the annual high-mileage pilgrimage to the Isle of Man for the TT races, and these were the first streetfighters. Others say-and I agree-that young British GSX-R riders removed their bikes’ fairings after crashes. They were already up to their Simpson Bandits in debt to buy the bikes; they still owed three years of payments and dared not claim on the insurance for fear of having their policies loaded to the point the road. The situation wasn’t helped by the Japanese firms replacement-parts pricing structure making new bodywork out of the question. And the old oil-cooled Gixxer Four is just about the best-looking Japanese motorcycle engine ever, so why not show it off?

In many ways it was getting back to our roots. Motorcycles have engines. Big heavy engines. They weren’t supposed to be the plastic-covered appliances that all the manufacturers’ fast, big-bore bikes were back then. Yes, full fairings are good, but there was no choice.

Because most of the bikes were crashed mid-stunt, it made sense to the nascent streetfighter builders to make their machines even more adept at wheelies and stoppies by fitting risers and a motocross handlebar.

Wire in some new headlights to tidy up the front end and all the boxes were checked. The bike was finished; you had yourself a streetfighter.

While the exact genesis of the breed may be up for interpretation, the first use of the evocative name of these bikes is not; My friend Clink coined it. This British photojournalist and serial bike builder used it first in print to describe a Harley. A hot-rodded Harley custom that used sportbike suspension and eschewed the chrome and engraving of the day for powdercoating and motorsport finishes. Clink also noticed the groundswell of Japanese custom sportbikes being built, mainly in the north of England, that would all later

be described as streetfighters. He is related to these bikes in the same way Tom Wolfe is to Kandy-Kolored Tangerine

Flake Streamline Babies. But Clink wouldn’t look as good in a white suit and Fedora.

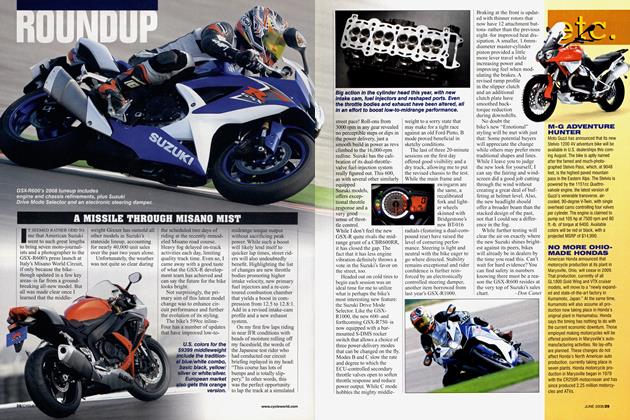

I have no idea to what degree the current staff of Triumph is aware of all this, but their bike’s big, black heart is certainly in the right place. This is the latest version, what I like to think of as Version 4.1, as it is a mainly cosmetic revamp of the fourth iteration of Speed Triple.

The Speed Triple is a factory streetfighter. With chromeshelled Bates-style twin headlights (subtly redesigned for ’08), moto-style bars, exposed engine and stumpy rear end, the Trip apes a hundred GSX-Rs built in Britain in the early to mid ’90s. The frame, a development of one introduced

by Triumph in 1997, was surely inspired by the streetfighter cult’s dream frame, the tubular aluminum Spondon Monster.

Back in the hollowed-out volcano and the Speed Triple is, Triumph tells me, an icon. Now, I don’t think a company is allowed to inform us that its own products are iconic; it’s up to the rest of the world to decide and for the manufacturers to graciously acknowledge the accolade. But in the global marketing moshpit we have been dragged into, such things are forgotten. Icon or not, the bike is important to Triumph.

It is the company’s best seller, with

47.000 Speed Triples sold globally since 1994, and an additional

10.000 slated for production in 2008. “It is the bike that best sums up the company,” I’m told. “Unique, distinctive, stylish, with bags of character.”

The essence of Triumph in one shiny $10,300 package. And as a Brit, Uve got to say I’m pretty proud of that take on things.

I’m proud because of all the things the Speed Triple does well-and there are plenty-it does misbehaving better than anything else. I like the fact a company I regard as pretty conservative loves its errant bad boy the most.

And V4.1 ’s improvements don’t dilute that hooligan spirit one bit.

The Triple now has a .4-inch-longer seat and longer pillion footpeg hangers, because existing buyers wanted better passenger-carrying arrangements. What difference less than an

inch of seat will make is up to Triumph’s customers to decide, but this minor change called for a whole new subframe, seat unit, plastic and undertray. My thinking is if you want to carry a pillion any more regularly than once an equinox, you want to choose a different bike. If your heart’s set on a Triumph, there are plenty that are better-equipped. The Speed Triple wasn’t built for two-up tootling with your sweetheart.

Escaping from the faux volcano and out onto the road.

I’m reminded that every crack of the throttle makes the front wheel go light. This 1050cc of British beef delivers big torque. Anyone can wheelie a Speed Triple. With an extra human perched above the rear-wheel spindle, you must have to ride like an undertaker to keep it sensible.

The rear end is all-new, but the most significant introduction are the multi-spoke wheels. The 17-inchers are a fresh design penned by Marabese (who designed the most recent Tiger) and cast in the Far East. They’re like nothing else on the market. The rear is beautifully presented due to the

fact it’s bolted to the Speed Triple’s trademark single-sided swingarm.

Another change that is significant for different reasons is Triumph’s first dabble with “labels.” The old chrome-plated steel handlebar (that really irked me thanks to its cheapest of the cheap feel) is replaced by a tapered aluminum MX-style bar made for Triumph by Magura-and Triumph wisely let Magura have its logo on the bar. Twenty-first-century motorcyclists like labels.

Triumph has also fitted Brembo brakes. These four-piston, four-pad calipers replace the Nissin radial jobs fitted to the 2007 model. In conjunction with a Nissin radial master cylinder, I’m told, they deliv-

er some “14 percent more braking force.” Okey-dokey, I’ll keep an eye out for that.

The British firm has made a number of minor but worthwhile aesthetic nips and tucks. Fork legs are now black, not gold. Indicators are the 675 Street Triple’s arrowhead design. Wiring and cabling in the area below the injectors has been given a more finished appearance. As have the radiator shrouds.

The only real engineering change is a gearbox design that’s been rolled out across all of Triumph’s 1050cc range. And it’s a good thing. The new box is wonderfully smooth with a super-short shifter throw, though I could still occasionally find neutral when shifting from first to second.

As an all-round package, the Triumph is the best of the factory streetfighters (more on that phrase soon). It might not be quite as attractive as an MV Brutale, but it’s easier to get serviced and it’s a lot less expensive. It fuels better than a Benelli and looks better than the increasingly confused Monster. The Euroje-only Moto Morini has a great engine, but try finding a dealer, even in Italy. Aprilia's Tuono has psychotic power levels but challenging looks. And even though their bikes were the very basis for the original streetfighers, the Japanese pretty much fail to build one worth considering-barring the Z 1000, and Kawasaki has gussied that up with dodgy manga exhaust cans. The KTM SuperDuke gives the Speed Triple a very good run in all areas. Even Triumph admits that. I loved the original Speed Triple, the crude café-racer of 1994, and this is the first Speed Triple since then I

could see myself buying. Yes, the changes are few but that’s all the bike needed. The comprehensively redesigned bike this model is based on was only introduced in 2005 (not long ago in Triumph terms). The only niggles are a slight stutter from the engine if you’re clumsy at small throttle openings. Don’t know if it was a fuelling issue or a bit of transmission lash. I only noticed it once in 120 miles on unfamiliar roads, so hardly an issue. The only other ointment-bound fly was the use of cheap plating on the oil-cooler lines. They discolor in a blink.

Otherwise, it was full rock ’n’ roll.

Streetfighters are all about a sportbike chassis and brutally simple aesthetics. The Speed Triple has a chassis and cycle parts in the right ballpark. Overall demeanor is not twitchy and light like a modern lOOOcc supersport. It’s tall in the seat and dynamically more like a 1992 GSX-R1100 than a 2007 GSX-R1000.

But (and it might be too late at this point in the story!) a streetfighter is not a bike that should be over-analyzed. Does it flick your switch? Does it sound good? Does it go so fast that your neck muscles double in size in the first month of ownership? That’s pretty much all the bases covered. Except one. Factory streetfighter. It’s an oxymoron. Like plastic sil-

verware or jumbo shrimp.

A proper streetfighter, to me at least, is a bike salvaged from a crash. A bike built with the minimum of tools but the maximum owner input. If it’s built in a factory, it’s not a streetfighter. It’s a muscle bike or er... I don’t know. Streetfighters belong to the people, not the global marketeers. But it’s such a cool name for a bunch of bikes that are exciting, totally usable and suitable for so many people that you can see why the suits in advertising wanted it.

But I’m over-analyzing when really I should be out riding the new Speed Triple, practicing my wheelies. O

View Full Issue

View Full Issue