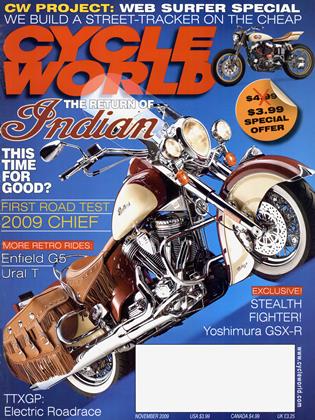

Isle of Man TTXGP

RACE WATCH

A petrolhead's guide to electric racing motorcycles

GARY INMAN

LET’S GET THINGS STRAIGHT: I’M A PETROLHEAD. I have new bikes, old bikes, an ancient scooter and a classic car. Suck, squeeze, bang and blow is the rhythm of my life. I’m defined by the internalcombustion engine. But when I heard about the inaugural TTXGP, a no-emissions motorcycle race to be held on the Isle of Man TT course during the TT fortnight, I was more than interested.

The Internet crackled with news of teams taking up the challenge to race.

As time passed, the premise became slightly less interesting as it turned out the rules and timescale favored electric bikes rather than any other possible technologies. Still, this was something amazing. And people knew it.

Twenty-two teams are listed in the TTX program. They come from six countries and three continents. They’ve come together on a sloping field that borders Glencrutchery Road, the TT’s

start/finish straight, and overlooks the Irish Sea. In contrast to the normal cheek-by-jowl TT race paddock, the feeling is airy.

There’s tons of room and only one semi (and that’s been borrowed from a local racer skipping this year’s TT). Most teams are camped in EZ-UPs of one size or another.

Michael Czysz is here in his uniform of black trousers, black shirt, expensive black sneakers, black sunglasses and black, slicked-back hair. He says he was coerced into building a bike by one of his employees, but the historic nature of what’s going down has certainly sunk in with him.

“We’re at the epicenter of motorcycle racing,” Czysz crows. “The mailman’s radio is set to what’s happening at the TT; it’s all-consuming.” Czysz’s view is echoed by Mission Motor’s hands-on team leader, Jeremy Cleland. “I must have watched over 100 TT on-board laps in my life,” says the former Ducati North America employee. “There are bigger fans of the TT than me, but not many.”

MotoCzysz, Mission Motors and fellow American entry Brammo make a triumvirate of West Coast-based outfits that have arrived with bikes of worldchampionship build quality. The same cannot be said for some of the other entries. Team Tork is a group of students from Pune University in India. Their bike is as ugly as warthog sex. It has one redeeming feature: the “scrutineering” sticker on its fairing. It is therefore free to be ridden at racing speeds around the 37.73-mile TT course by experienced TT-racer John Crellin.

This is Wednesday of race week. The Supersport 600 and Superstock TT races will be held today. So will the second proper TTXGP practice-one lap of the island between the feature races. The electric bikes form up, two by two, in the holding area as the TT regulars, deep in thought, file past to meet their 600s. Some of the TTX circus look incongruous in comparison to the racers whose bikes, teams and attitudes have been honed by a century of competition.

Cedric Lynch is a totemic figure in the electric-vehicle world. His long gray hair is pulled back in a ponytail.

He’s wearing grubby sneakers. I don’t know why I noticed this, but it becomes significant because it turns out he’s normally barefoot. Lynch’s speech has a dreamy, very English but unusual lilt. He is incredibly engaging and likeable but stands out like...well, an electrohippy in a motorcycle race paddock.

Lynch designed the Indian-made Agni DC motors that power his and a

number of the other entries. His motors also hold the World Electric Waterspeed record, with a run of 68.09 mph on England’s Lake Coniston (where Donald Campbell flipped Bluebird and never came back).

“We manufacture these motors in India and entered the race to promote them,” he says. “The TTX organizers put us in touch with the rider, Robert Barber.

We asked him what bike he’d like us to convert for the race, and he recommended a Suzuki GSX-R750. He arranged for us to buy this one without its engine and we installed the electrics into it.”

The result, though not as offensive as Team Tork’s entry, is far from pretty. Head-on, the Agni factory entry looks like a scruffy GSX-R painted with rattle cans, but from the side, the bike’s motherboard-the motor controllerrises, all sharp-edged, like a Titanicwrecking iceberg in the area where the shapely petrol tank used to sit.

“We have two DC electric motors,” Lynch continues. “We don’t have one powerful enough to use all the power we have available from the battery. The motors are simply coupled with a shaft and then drive the rear wheel with a fixed ratio. It’s a twist-and-go machine.”

Only two entries run a gearbox, and every team uses lithium-ion cells. Lithium ion is a family that contains lithium iron (that’s confusing for the petrolhead, ion and iron), lithium manganese, lithium cobalt dioxide, lithium... Well, you get the idea.

“Lithium batteries hold about four times the energy a lead-acid battery of same weight could hold,” Lynch explains.

Still, it becomes clear, as I spend more time with my new electric friends, the key to any power source aiming to compete with my beloved internal-combustion engine is energy density.

Eighteen liters of unleaded fuel equates to 573 megajoules of energy. A> figure of 36 MJ is what most TTXGP competitors roll up to the line with for their single lap. The internal-combustion engine wastes a lot of its energy in the form of heat, whereas the batteries waste very little. Thirty-six MJs are enough for one lap at a given speed, that being nowhere near what the same riders achieve on a conventional, 600cc internal-combustion-engine-powered motorcycle. So, why not pack more power? The bikes can’t physically carry it without being unwieldy around the demanding Mountain course.

Lynch, who commutes 20 miles per day around the outskirts of London on an electric motorcycle of his own design-charged by the solar panels on his roof, no less-believes a more aerodynamic “feet-forward” motorcycle could complete four laps at racing speeds with the same motive power and charge. “Wind resistance is the biggest obstacle,” he says. “Motorcycles are very poor aerodynamically.”

As Michael Dunlop, son of Robert, nephew of Joey, wins the Superport race, the electric bikes prepare for takeoff. This is their last chance to practice before Friday’s race. The pressure is on. In fact, the pressure’s been on from the get-go. The timescale to build these cutting-edge alternative racers has meant a lot of bikes have lined up with little testing. A few bikes have more bugs than a tramp’s vest.

To the sound of college-football whoops, the bikes are flagged off, one at a time, for a timed practice.

Because of the nigh-on-38-miles-long n 'hire of the TT, spectating is a different exA ïrience-especially for a one-lapper.

So, as I wanted to see the bikes set off, there’s not a great deal to do. But 27 minutes-the lap time of the fastest bike-passes in a blink in the TT paddock. Lynch’s Agni Motors GSX-R romps home fastest, just as it was in first practice.

The MotoCzysz entry, with American Mark Miller on board, limps in more than 20 minutes later. It ran out of juice, paused to catch its e-breath, then managed to make it home, again to much whooping and hollering.

Every team wants to win, but for a lot of them, there’s something bigger at stake: the entire image of their chosen propulsion method. If-and it won’t happen, but let’s just imagine-every electric bike failed to finish, the credibility damage inflicted would be disastrous.

So no one wants to see a fellow competitor fail. Add in the TT’s remorseless nature, and everyone really just wants the best man to win and everyone else get back for a cold one.

As his bike is bundled into the back of a panel van to be probed off-site,

Czysz gives me 10 minutes ofTTX background. The race had spiked the interest of a bunch of electrical engineers acquainted with MotoCzysz’s Adrian Hawkins.

“One of our employees asked about the spare chassis we had and explained what he wanted it for,” Czysz relates.

“I said, ‘Man, that sounds cool,’ but I only wanted to get involved if it was a MotoCzysz project.

“We put together a team meeting,” he goes on. “We don’t have any electrical experience. All the outside people at the table promised a lot, but they all delivered nothing. They were all about arm-waving, but when we asked them to do something, they all fell off quite quickly.”

Czysz and Hawkins were left to pick up the pieces. And learn fast. Czysz decided his bike should be powered by three “Agni-style pancake motors.” Why?

“How exciting is it to get on a bike that has the equivalent of 30 horsepower and does 60-70 mph,” Czysz replies. “That’s not exciting. I wouldn’t buy one, so why would I want to build one?

“We have 120 horsepower,” he continues. “Electric bikes are perfect in their linear delivery of power, and it’s very early on. But do you want that in a bike that’s leaned over? No, but you can contour it. We ran 122 mph in early tests without a fairing. We think it’s good for 150 mph.”

That’s big talk. The Agni touched 100 mph on Sulby Straight. These bikes can go faster, but 150 mph would flatten the batteries in a blink of an LED. So it’s impressive but completely theoretical. The energy density of the batteries needs to increase so much for an electric sportbike to do anything more than an exhilarating, near-silent spurt before a long recharge that the electric sportbike is just a pipe dream.

Unless you work for Mission Motors, that is. Mission plans to build electric sportbikes and is taking deposits on the $69K machines. The prototype streetbike is an astonishing-looking machine.

“The goal isn’t to sell a handful of bikes to a few rich people,” says Mission’s Geland, who cut his electric teeth with Tesla, the electric-sports-car firm. “We want to make it desirable and affordable to the masses as much as possible. That won’t take incredibly long.” We’ll see...

“We wouldn’t be in this game if we didn’t think this technology was going to have a sizable impact on a lot of the environmental issues out there,” Geland adds. “Petrol isn’t going to last forever. Everyone knows that. We want to be a catalyst for change.”

But Mission is the only company openly building sportbikes. Everyone else involved in the TTX is concentrating on commuters, off-roaders and agricultural workhorses-or is just here for the challenge.

Dawn comes for the biggest day on the TT calendar: Senior day. To see 13 electric-racing motorcycles line up for a 10:45 a.m. race start is not something many people would have bet on. And although riders like Gary Johnson (who will finish third in this afternoon’s Senior TT) are paying a lot of interest > to some of the bikes, word is this race nearly caused a bitter split between the Isle of Man government and the TT’s organizing body.

The problem, says a high-ranking source who wishes to remain anonymous, is twofold. “We stopped the popular 125 and 250cc TTs because we said there wasn’t time for everyone to practice properly. We saw it as a safety issue. But then the TTX comes along and suddenly there’s time. Also, we have had ongoing concerns about if one of these bikes crashes and catches fire. The marshals have raised the problem, and it’s just been swept under the carpet. They’re very unhappy about it.”

Additionally, if the rumors are true, the main supporter of the TTX within the Manx government has been open about his dislike of the TT itself.

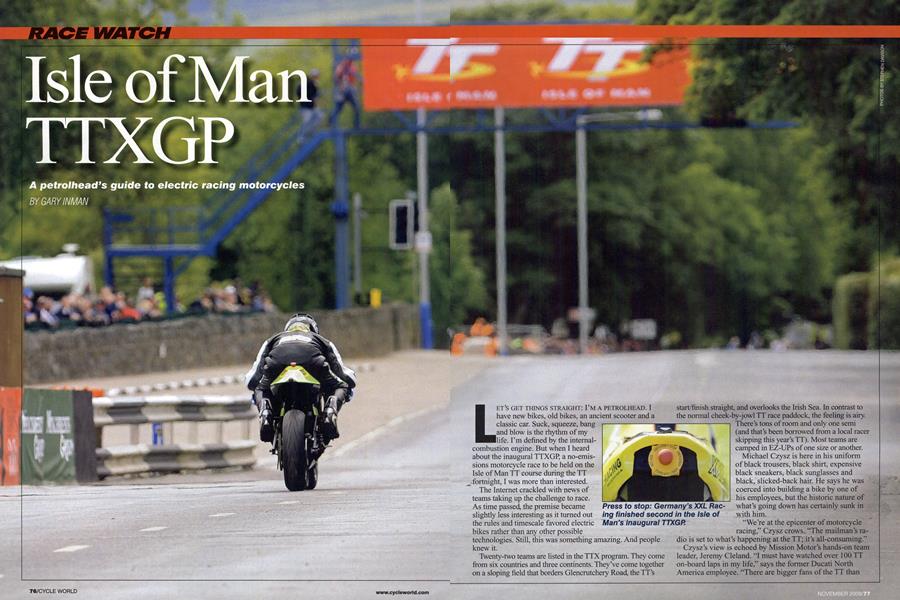

The drama behind the scenes helps make up for the lack of action at the start of the TTXGP. As the flag drops and Tom Montano adopts a tuck on the Mission entry, the feeling is historic, not thrilling. Electric bikes are virtually silent, the only noise coming from the tires and drive chain. These early electric bikes have been described as the anti-Harley. If electric sportbikes are the future, a lot of pedestrians are going to get run over. And a lot of riders are going to hit unaware wildlife. At speed, these machines emit a Star Wars X-wing Starfighter whine.

“Initially, you think, Ts it going?’ But once the thing starts to move, the riding experience-throttle response, for example-is very similar to a conventional motorcycle,” says Montano. “Not having gears is strange at first, but after a while you get over that.”

From the first timing point, it's clear the Agni X01 is in a class of its own.

It’s dominated all week. But has anyone been confident enough to sandbag, winding up the power, after experimenting with range all week? The thought keeps me on the edge of my seat, but the answer is no. Czysz’s mood goes as black as his slacks when the El pc digital Superbike stops again. He’s not seen again, which is a shame, because even though this could be regarded as a failure, it isn’t; it’s an early (very public) test glitch. The quality of his entry gave the event real class.

Rob Barber, on the Agni, hits 102 mph through the speed trap at Sulby and walks away with the victory: 25 minutes, 53.5 seconds at 87.434 mph. The speed is significant because it beats the best-ever 50cc time set by Ralph Bryans on a Honda in 1966-Barber and Lynch’s modest goal.

America is well-represented in the final standings. In the Pro Class (essentially bigger-budget bikes), Brammo is third, Mission fourth. In the Open Class (bikes that could be compulsorily purchased after the race for £20,000), American teams Electric Motorsport and Barefoot come in first and second. Team Tork’s warthog-sex machine comes in third (though, sadly and soberingly, its rider, John Crellin, is killed in the afternoon’s Senior TT).

Ultimately, the TTXGP result means something to a handful of people, but the fact the race happened at all could be significant to the whole planet. Electric bikes will offer an alternative for the future, but it’s disappointing that the FIM has put its weight exclusively behind electricity rather than other technologies.

I thought the TTXGP was about green issues and different thinking. Seems to me, it’s nothing more than a new niche racing class. We’re one race down and the vision has already been lost. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontA Changing World

November 2009 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupUps & Downs

November 2009 -

Roundup

RoundupGore Lockout: Death of the Zipper?

November 2009 By Mathew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupTransformed

November 2009 By Mark Cernicky -

Roundup

RoundupWar of the Words

November 2009 By Kevin Cameron -

25 Years Ago November 1984

November 2009 By Mark Hoyer