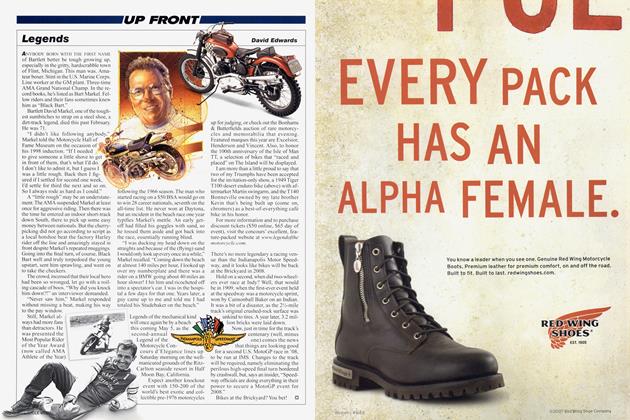

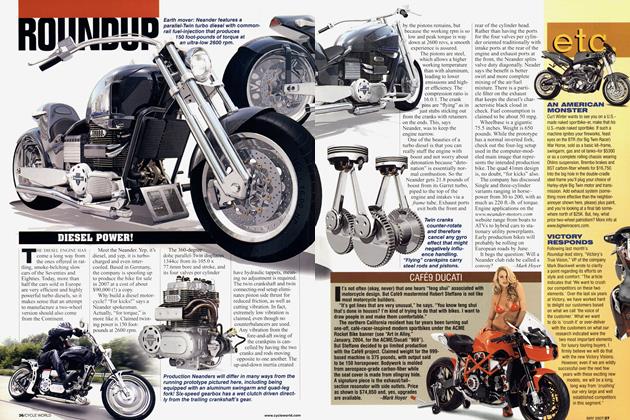

MADNESS IN METAL

A Ducati 999R under the influence of one seriously deranged German

GARY INMAN

FOR SIX MONTHS I LIVED ON SALTINES AND

beer,” says Thorsten Durbahn. “I lost 30 pounds. It was hard, but I’ll spend a week working out how to save a half-pound from my Ducati’s overall weight, so it was necessary.”

I admire, celebrate, even love the motorcycle obsessive. But for a few tense minutes after meeting Dr. D., the maddest of motorcycle scientists, I wondered if I’d bitten off more than I could chew.

When I arrive at the farm building on the far outskirts of a small German village, Durbahn, a 38-yearold Hamburg resident, is waiting outside next to his battered panel van.

“My young man has run out of petrol on the autobahn, make yourself comfortable,” he says as he points to the door of the shop.

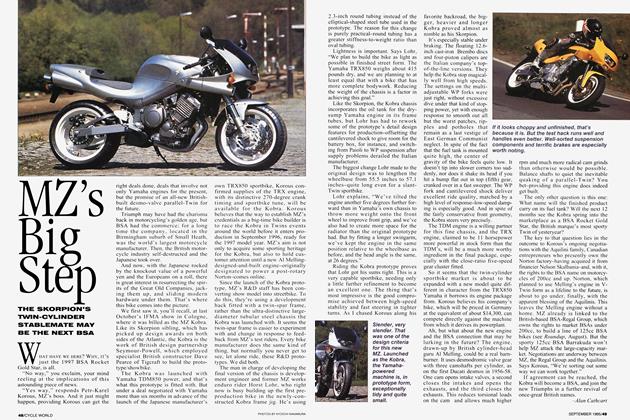

Comfortable? It could be difficult. Durbhan’s workshop’s walls are lined with tools, machinery and shelving holding tons of motorcycling flotsam. Near the door are skyscrapers of beer crates. At the far end there is an area where his “young man,” Constantine, makes paperthin carbon-fiber bodywork. His workbench looks like an obsessive compulsive artist’s studio. Spilled chemicals are built up like mixed oil paint, holding dirty jars in a relentless, gluey grip. Strange clamping devices hold together works in progress. And there are half-finished seat units awaiting trimming, hefty molds, cheap drills with strange bits for mixing the epoxy used to stiffen the cloth-like sheets of carbon-fiber.

Hanging from the ceiling is an upside-down 1970s lamp and dozens of rolls of fly paper. Mice scurry around the floor. It looks like a movie set. It’s amazing that anything as beautiful and technologically advanced as Durbahn’s glorious motorcycles emerges from these premises. It’s equally amazing that the German authorities allow a business to operate in these conditions. It’s illegal. Durbahn uses workshops like terrorist cells use safe houses. When the authorities get too close (or shut him down) he moves on. He’s a motorcycle radical. A hardcore fundamentalist. Maybe just a mentalist.

I’ve come to see one of his motorcycles. It’s the most extreme Ducati Testastretta in the world. The product of deep thinking and distilled engineering skill. The Durbahn 999 V2.

* I * he concept was to lower the center of gravity and •A* compress the center of gravity,” says Durbahn. All the Japanese manufacturers (and the pioneers at Buell) have been making big noises about this, but they describe it as the

search for mass centralization.

Durbahn was also driven by a mischievous, gut-felt desire, he says, “to shock the Ducati community. I hate them. All the lawyers and dentists!”

Ducatisti, he doesn’t really hate you. I’m sure he’s just making a point. Durbahn is a student of philosophy, particularly fond of Immanuel Kant. Further research shows Kant wrote, “Intuition and concepts constitute the elements of all our knowledge, so that neither concepts without an intuition in some way corresponding to them, nor intuition without concepts, can yield knowledge.”

Durbahn has both concepts and intuition. The 999R was bought brand-new in November, 2003. It remained untouched for only 90 minutes before it was completely stripped and left in pieces. Regularly it would be inspected over a period of three months while Durbahn decided how best to reach his mass-centralized goal.

During the strip-down every item was weighed. “We laughed as we lifted pieces off the bike,” says assistant Constantine. Durbahn passes me the original 999’s exhaust canister and taillight assembly. It feels about the same weight as an RZ350 engine. It’s ridiculous. Where did it all go wrong? If mass centralization is the way to go, why did Ducati hang this monstrosity so far from the center of the bike?

Durbahn started his work elsewhere with an extreme solution: relocating the fuel tank. It was at first going to be fabricated from carbon-fiber but, says Durbahn, “I’m older, I’m more likely to crash, and aluminum will survive better.” The finished fuel reservoir looks like a piece of flattened chew-

ing gum stuck to the side of the hot motorcycle. It’s made from 1.5mm-thick alloy and holds 3.7 gallons.

The after-effect of the audacious fuel tank was extreme radiator relocation. The huge, flat rad has what its owner describes as a “Z flow.” So the intake and outlet are both next to each other. Neat. Neatness is another big thing for Durbahn. And it isn’t just plonked there because Honda did so with its RC51 and Super Hawk Twins. Hours of thought went into the positioning and airflow.

“The RC51 radiators don’t work,” claims the D-man, “so I formed the inside of the fairing to produce a ram-air effect for the radiator.”

Amazingly the Durbahn 999 V2 doesn’t look any wider than a standard 999, though I didn’t have the benefit of having them side by side.

urbahn describes the stock 999’s riding position as “a horror.” He’s improved it by making the dummy tank

much shorter than the original so the stretch to the bars isn’t as extreme. He’s also raised the seat height by 2 inches.

The bike’s bodywork is so beautiful it makes GP bikes look dumpy. The snout was made by taking an MV Agusta F4 top fairing and pushing it at its extremities until its front aspect was about 60 percent of the original. Then he made a mold and modified the screen aperture.

The whole fairing is completely new. “It took 900 hours to make the molds,” he explains. “At times I got to the end of my powers and had to do something else or would have gone mad.”

I leave the statement hanging while I take another look around his lair...

The bare bodywork weighs the same as a dirty thought. He has two sets of bodywork. One painted for photos, the other bare for action. The paint weighs a little over 4 pounds. Durbahn gets visibly upset about adding any unnecessary weight.

Fixings are at an absolute minimum. The instrument binnacle/fairing bracket forms forks that the top fairing slides onto. It’s a simple push-fit. And the right-hand side of the fairing has shark gills that allow the force-feed air blown through the radiator to escape efficiently.

A standard 999 Due looks pretentious in comparison.

A constant obsession of this and every other Durbahn project is weight. He refers to it constantly. He talks in ounces and pounds, seemingly knowing the weight of every component. This leads to the use of some extreme

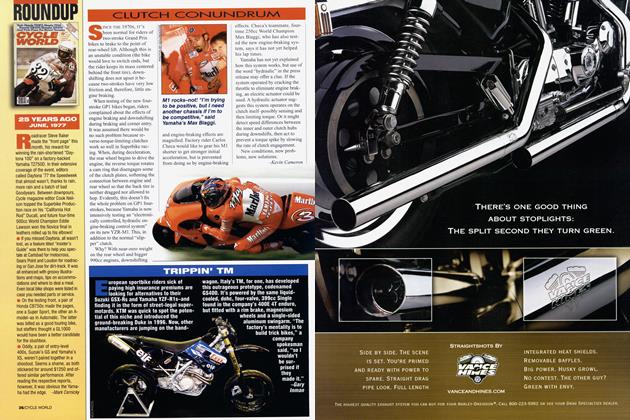

components. Like the QAT fork.

Durbahn claims only 30 or so sets of this fork were made, production starting back in 1992. The machining on them is incredible. They were built by a company in the armaments industry and have the feel of a sniper’s rifle. They also have no springs and, consequently, weigh 6.25 pounds less than high-spec Qhlins. Recently, Durbahn bought an ex-German Superbike Kawasaki ZX-R750 racer because it was fitted with a QAT fork. He kept the fork and gave the rest of the bike to Constantine.

At the rear, the shock is a complete one-off by car-suspension gurus KW. They offered to make one for Durbahn and the muted colors are right up his street. He has an aversion to yellow and gold.

Wheels are forged-magnesium PVMs, also made to Durbahn’s own spec. They’re 1.5 pounds a pair lighter due to thinner spokes than standard mag PVMs. The rear hub is machined to allow the master cylinder to hide behind the later-style 999 swingarm. Front calipers are Brembo, while the rear caliper and front discs are ISR. Those twin discs are 320mm diameter, soon to be reduced to 290mm to save more weight.

The engine hasn’t been extensively tuned, being treated to Pistai forged pistons, perfect cam timing and a balanced crank. But every small steel bolt, spacer and widget within the engine was given to an engineering shop to replicate in titanium. Everything has been trimmed, shaved and honed. The crank has lost its enormous flywheel and water pump drive. Coolant is now circulated by an electric pump. Again, to save weight.

The clutch has been converted to cable operation, not

only to save a few ounces but also to give a beautiful, light, consistent feel. I took one of Durbahn’s little cable clutch actuator assemblies home and played with it for hours.

The clutch itself has been changed from dry to wet using a modified GSX-R assembly.

Again, it’s lighter.

The clutch itself uses Hyperplate

aluminum clutch plates.

Durbahn’s Ducati doesn’t race, it’s a test mule for his new products and theories and sees regular track-day action. Without a back-to-back test with a tuned 999 wearing a few of Ducati’s own go-faster parts (impractical in a German winter), it’s hard to say if he has improved on Ducati’s former flagship superbike. But as the Theodore Roosevelt quote Durbahn uses on his website states, “Far better it is to dare mighty things, to win glorious triumphs, even though checkered by failure, than to take rank with those poor spirits who neither enjoy much nor suffer much, because they live in the gray twilight that knows not victory nor defeat.”

Durbahn, it’s safe to say, does not do gray. □