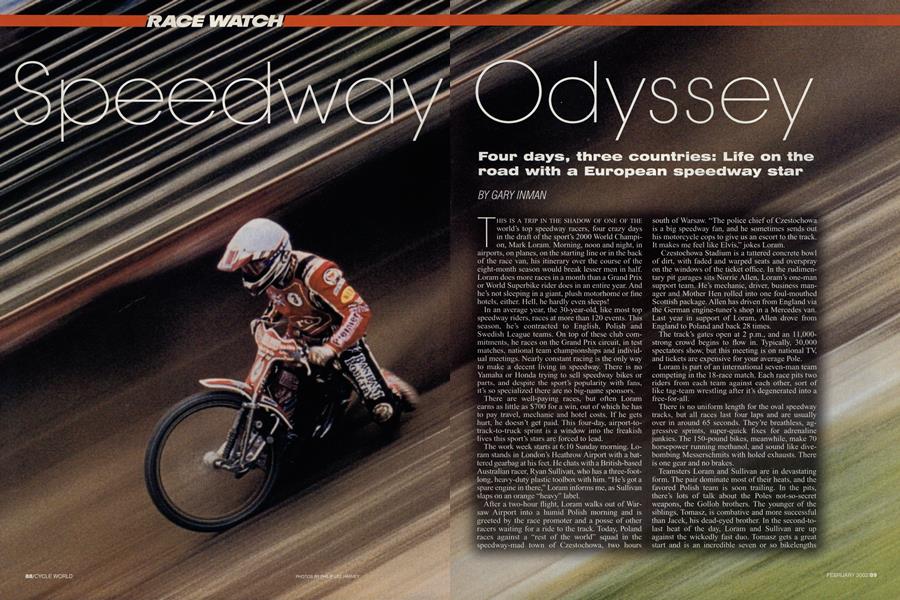

SpeedWay Odyssey

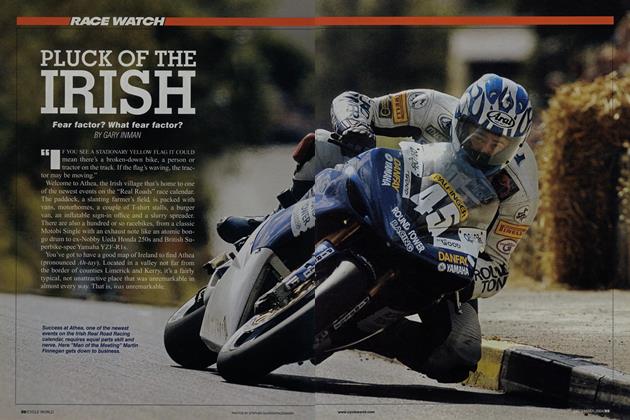

RACE WATCH

Four days, three countries: Life on the road with a European speedway star

GARY INMAN

THIS IS A TRIP IN THE SHADOW OF ONE OF THE world’s top speedway racers, four crazy days in the draft of the sport’s 2000 World Champion, Mark Loram. Morning, noon and night, in airports, on planes, on the starting line or in the back of the race van, his itinerary over the course of the eight-month season would break lesser men in half. Loram does more races in a month than a Grand Prix or World Superbike rider does in an entire year. And he’s not sleeping in a giant, plush motorhome or fine hotels, either. Hell, he hardly even sleeps!

In an average year, the 30-year-old, like most top speedway riders, races at more than 120 events. This season, he’s contracted to English, Polish and Swedish League teams. On top of these club commitments, he races on the Grand Prix circuit, in test matches, national team championships and individual meetings. Nearly constant racing is the only way to make a decent living in speedway. There is no Yamaha or Honda trying to sell speedway bikes or parts, and despite the sport’s popularity with fans, it’s so specialized there are no big-name sponsors.

There are well-paying races, but often Loram earns as little as $700 for a win, out of which he has to pay travel, mechanic and hotel costs. If he gets hurt, he doesn’t get paid. This four-day, airport-totrack-to-truck sprint is a window into the freakish lives this sport’s stars are forced to lead.

The work week starts at 6:10 Sunday morning. Loram stands in London’s Heathrow Airport with a battered gearbag at his feet. He chats with a British-based Australian racer, Ryan Sullivan, who has a three-footlong, heavy-duty plastic toolbox with him. “He’s got a spare engine in there,” Loram informs me, as Sullivan slaps on an orange “heavy” label.

After a two-hour flight, Loram walks out of Warsaw Airport into a humid Polish morning and is greeted by the race promoter and a posse of other racers waiting for a ride to the track. Today, Poland races against a “rest of the world” squad in the speedway-mad town of Czestochowa, two hours south of Warsaw. “The police chief of Czestochowa is a big speedway fan, and he sometimes sends out his motorcycle cops to give us an escort to the track. It makes me feel like Elvis,” jokes Loram.

Czestochowa Stadium is a tattered concrete bowl of dirt, with faded and warped seats and overspray on the windows of the ticket office. In the rudimentary pit garages sits Norrie Allen, Loram’s one-man support team. He’s mechanic, driver, business manager and Mother Hen rolled into one foul-mouthed Scottish package. Allen has driven from England via the German engine-tuner’s shop in a Mercedes van. Last year in support of Loram, Allen drove from England to Poland and back 28 times.

The track’s gates open at 2 p.m., and an 11,000strong crowd begins to flow in. Typically, 30,000 spectators show, but this meeting is on national TV, and tickets are expensive for your average Pole.

Loram is part of an international seven-man team competing in the 18-race match. Each race pits two riders from each team against each other, sort of like tag-team wrestling after it’s degenerated into a free-for-all.

There is no uniform length for the oval speedway tracks, but all races last four laps and are usually over in around 65 seconds. They’re breathless, aggressive sprints, super-quick fixes for adrenaline junkies. The 150-pound bikes, meanwhile, make 70 horsepower running methanol, and sound like divebombing Messerschmits with holed exhausts. There is one gear and no brakes.

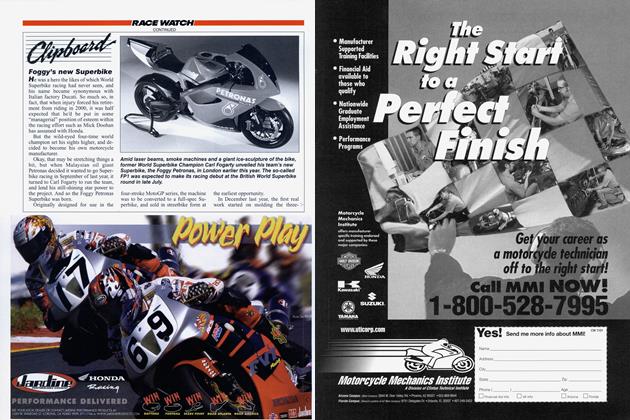

Teamsters Loram and Sullivan are in devastating form. The pair dominate most of their heats, and the favored Polish team is soon trailing. In the pits, there’s lots of talk about the Poles not-so-secret weapons, the Gollob brothers. The younger of the siblings, Tomasz, is combative and more successful than Jacek, his dead-eyed brother. In the second-tolast heat of the day, Loram and Sullivan are up against the wickedly fast duo. Tomasz gets a great start and is an incredible seven or so bikelengths ahead with two laps to go. Seeing his brother’s second place in danger from the charging Loram, he backs off to ride side-by-side with Jacek to block overtaking moves.

Infuritated by the arrogance of this tactic, Loram throws everything at them on the last lap, passes the brothers and takes the win. The crowd goes wild-strangely, with respect. The stars of Polish speedway have been humbled by this Englishman, but they sing his name in praise as he makes a lap of honor.

Removing his helmet and wiping the dirt, sweat and snot from his flushed face, Loram explains his popularity. “The Polish appreciate a tryer,” he says modestly.

After the win, Loram and Allen pack up and hit the road. At 11:30 that night, the traffic at the German border is noseto-tail. Allen spots a gap in the lined-up trucks and veers off the main highway onto a narrow lane through a forest. “We could’ve been stuck in that for three hours,” Allen says over the rumble of the tires on the poor road surface. A veteran of countless border crossings and thousands of miles of truck travel, he almost always has an alternate plan handy. Just 25 minutes later, we’re at another checkpoint being interrogated by a youth in a U-Boat Kommandant’s cap. He slides the side door of the van open and flashes the beam of his Apollo 11-sized flashlight directly into Loram’s bleary eyes. The exhausted rider has been asleep since we left the track four hours earlier. Like a cockroach, he lives in little more than an unlit crack behind the seats. Think Mert Lawwill in On Any Sunday, not Valentino Rossi or Troy Bayliss in a modem race paddock. Loram’s “bed” is a padded shelf in the van’s small living quarters, which comprise a TV, fridge and a couple of cupboards. After they’re grudgingly waved through, Loram dozes off again.

By 5 a.m. Monday, we’re 70 miles from Dortmund. After a full day wrenching followed by 11 hours behind the wheel, Allen finally throws in the towel and wakes Loram so he can take over. “I hate being behind this round thing,” Loram grumbles as he climbs into the driver’s seat. He sticks in a punk-rock CD and Allen sleeps through the three-chord onslaught as the van heads toward the Channel Tunnel at 80 mph.

That night at 6:30, 24 hours after leaving Czestochowa, Loram is ready to race for his English home team, the Pe terborough Panthers, who are taking on the Oxford Cheetahs. The heats come like hammer blows in quick succession. Loram has a good day, but Oxford is too strong, and the visiting team's fans go home happier.

After the race meeting, we drive straight to a Heathrow Airport hotel as Loram’s next racing obligation is to his Swedish team. Despite staying less than three miles away from the airport, Loram misses his 6:45 a.m. flight to Copenhagen. So much for the tightly orchestrated schedule! He could have walked on the plane, but in his luggage is a spare engine he’s delivering to his Swedish pit crew, and the ground staff are digging their heels in about not being able to get it on the plane. Within minutes, he’s arranged a later flight. Because of moments such as this, speedway racers always pay a little bit more for changeable tickets.

In Jönköpping, Sweden (the original home of Husqvarna), another friend picks up Loram and, coincidentally, Ryan Sullivan, who’s racing against Loram for the top spot in the league. During the two-hour drive to the track, the windshield wipers never stop. Speedway does not run in the rain or if tracks are waterlogged.

As we pull into the circuit, officials debate about holding the race, but send out a tractor to scrape the track, and finally the meeting is a go. Loram tenses against the cold as he stands under the long, open-sided tin-roof shed that serves as the communal garage for 14 riders, 28 bikes and assorted mechanics. Loram lines up, the starting tapes fly, and he slides away as heavy rain begins to fall again. Loram is third in the first corner, his machine bucking erratically. Speedway bikes don’t have rear suspension, and the leading-link fork is damped by a shock absorber the size and diameter of a compact bicycle pump, using a “spring” that’s more like a big rubber band. These bikes are not made for riding rough ground, and the rain has made the Swedish track as rough as they come. After leaving the small airport near the track at 5:30 a.m., Loram is on the return flight to England. Next to him sits Hans Andersen, a Danish racer. At 20, Andersen is in his first year as a Pro in England and, like Loram, races in three different countries virtually every week. He’s one of the youngest riders in the league, and he’s still got a lot to learn. “He’s getting a reputation for being a bit of a headcase,” says Loram of his traveling companion. “A few riders have already given him a smack after races for pulling dangerous moves.”

As Loram returns to the pits, wearing a thick coat of filth, the match is abandoned. He’s traveled halfway across Europe for one race, expending effort and money for nothing. Rain-outs are an occupational hazard. Loram and Allen have driven all the way to Poland only to turn around and head right back to England more than a half-dozen times.

Andersen may be young, but Loram turned professional at the tender age of 16, as early as is legally possible. “I rode the night after my final exams. I didn’t do too badly at school, but I just wanted to get out of the place and ride my bike,” he says.

Outside Heathrow, Loram is met by Allen, who had a "free" day while his rider was in Sweden. Of course, Allen spent the time preparing bikes for that night's meeting in Poole, on England's south coast. Poole is a speedway town, and civic pride and passion are directed toward the burg's successful race team.

At 4:15 Wednesday afternoon, the sun begins to dip and the paddock comes alive with the staccato rap of racebikes being warmed up on their stands. A percussion accompaniment comes from the steel shoes the riders strap to their left boots. It gives the riders a clunking, swaggering walk that evokes the image of beaten and battered rodeo riders. Of course, many of the racers don’t need an inch of metal strapped to one of their feet to walk with a limp.

The Poole squad is riding well, and after 10 of 15 heats, Loram is the only hope to save the day for his Peterborough team. True to form, he doesn’t get a great start, but by the turn-in point of the second corner he’s on the tail of young Andersen, one of Poole’s most popular riders. Suddenly, there’s a tornado of dust, and the race is stopped as the pair collide and crash to the ground. Allen and the team run to Loram, still sitting in the dirt on the track, who says Andersen swerved right before turning left, taking his line and forcing him to bail off the bike.

As Loram hobbles back to the pits, Andersen is taken to the hospital with a broken leg. It’s another example of the champion’s experience. A split-second decision to jump off the back of his racebike and slide to a stop, separately from the machine, means he can finish the meeting, go home to his girlfriend and race for the rest of the season. When speedway riders don’t race they don’t get paid, as all wages are completely related to results.

After the meeting, Loram has a beer with the fans before curling his battered, aching body onto the shelf in the back of the van for a couple of hours sleep on the way back home. Tomorrow is a day off for the racer, but Allen has to drive to Germany to get an engine rebuilt. On Saturday, Loram will race as a stand-in for an injured rider for another British team, a practice regularly used in speedway and an opportunity to earn a little extra money. On Monday, the whole crazy cycle begins again.

“It’s a good life. I get to travel and ride my bike and I make a reasonable living,” Loram says with an unflappable air. “I race so much I don’t need to practice, and at the end of the season, that’s it. Normally, I don’t look at a speedway bike until the following year.”

Oh well, mate, only another four months and 65 meetings to go... □