The TT Centenary

We had to be there. And we couldn't just take the ferry.

GARY INMAN

RACE WATCH

Friday, June 1: The Journey

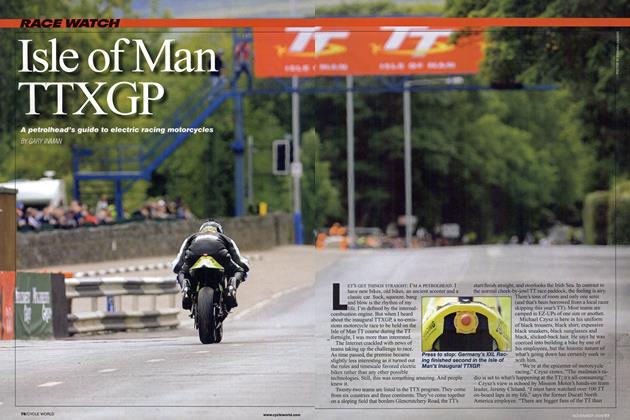

THE CAPTAIN IS NERVOUS. HE PUTS A CIGARETTE to his lips, picks up a lighter then remembers he doesn't smoke. We haven't heard a word from him in 30 minutes. We're in his North Wales garden under a faultless blue sky. Fifty-five miles away, the Isle of Man is gearing up for the first race of the Centenary TT. If you love motorcycle racing, it's the only show in town. And because of that, every ferry, airline flight and hotel room is booked.

Three months ago, inspired by racers Joey and Robert Dunlop’s legendary trips from Northern Ireland to the TT, I e-mailed the captain asking, “What’s the chance of getting two bikes and two people over to the Isle of Man on a trawler?”

“It might be expensive,” he replied. “Or we could take my RIB.” The RIB is a rigid inflatable, a 20-footlong rubber dinghy with a large Honda outboard stuck on the back. It wasn’t perfect but it was our only option. So we made plans to sail from Holyhead on Anglesey, North Wales, to Douglas on June 1.

The captain soon began to regret his offer. Now, as we’re about to shove off, his decision to volunteer is haunting him. He decided two days earlier to have the outboard serviced. The mechanic discovered an oil seal on its way out and seawater in the gearbox. Replacement parts were ordered the day before we were scheduled to leave.

Originally, we wanted to stuff everything in the boat on Thursday night and spend the evening perfecting our packing to ensure the bikes-a pair of lightweight 125cc two-strokes, an Aprilia and a Derbi-didn’t get bent or, crucially, pop the boat. We wanted to be in the water by 10 a.m. on Friday, the last day of TT practice and only 26 hours before the Superbike race. Instead, it’s now 11 a.m. on Friday, and the bikes still aren’t on board. We don’t even know if they’ll fit. Our plan is going to hell, and the captain’s tongue has retreated into its shell as he sits staring into the middle distance.

Our crew-Fly the photographer, Easty, a Ducati-riding trained yachtsman, and me-is standing around the garden, itching to get going. The captain finally gets on the phone and rings his mechanic. The parts still haven’t arrived.

He decides we’ll sail with the dodgy motor. He figures if he hadn’t had it serviced, we wouldn’t have known about the seal and would’ve gone anyway. The logic is skewed of course, but we’re desperate to get going.

Finally, at 4:30 p.m., the RIB, still on its trailer, is dragged to a slip and slid

into the water. The captain is a respected member of the local maritime community and doesn’t want to load the bikes in front of the coastguard lookout or near anyone who might tell his employers and jeopardize his career. So as the RIB motors to the designated launch point, I pop an anti-seasickness tablet and ride three miles along the coast to the fish quay. Rolling down the ramp to the floating jetty, I’m no longer itching to get going. Below, the RIB is tied up next to rusty fishing trawlers. It looks tiny. Everything we want to take-our camping gear, a week’s clothing for four men, camera equipment, a self-deploying lifeboat and four flotation suits-sits on the dock.

We remove the Derbi’s footrests and promptly drop one of the fasteners between the jetty planks into the sea. That’s followed soon after by a 13mm wrench. All the while, our now-talkative captain is jabbering away. “The way the RIB is designed,” he says proudly, “it’s unsinkable, even if it’s holed.” Isn’t that what they said about the Titanic?

The bikes look awfully big, and the RIB looks awfully small. Young trawlermen over and ask what we’re doing. They smile when we tell them our plan.

says we should’ve asked him; he has an onboard crane. I shoot our captain a contemptuous glare.

Cheap camping mats are gaffer-taped to the bikes’ pointiest bits. Then, with two men on the boat and two on the dock, the Derbi is lowered into place. It’s a tight fit. A couple of inches longer or wider and it wouldn’t have fit. With yard-square between the bike and the ’s only room for one next to no

padding. With little room to maneuver, the little Aprilia RSI25 Fortuna replica slots in, and the bikes are lashed tight.

Even though we’re still tied to the dock, one nerve-wracking element of the trip is over. A touch after 5:30 p.m., seven-plus hours behind schedule, we’re trussed in flotation suits, squashed into the remaining free areas of the boat and the ropes are finally untied.

Excitement flushes fear out of my system. As we cruise past the harbor, the

captain radios the coastguard to say we’re on our way. They wish us a safe journey. When we set our departure date three months earlier, we couldn’t have hoped for more perfect weather. The sun burns our skin, but that’s the only discomfort we face. The Irish Sea, known to swallow trawlers and crush racing yachts, is as flat as glass.

It’s hard to talk above the roar of the wind, so as we hit 25 knots, the four of us just grin at each other. I keep looking

back at the cliffs of Holyhead. The crossing is 55 miles, due north, and there’s only a brief period between the Welsh coast disappearing and Snaefell, the mountain of the TT’s Mountain Course, appearing through the haze. We’re still a good hour out, but our already high spirits go stratospheric. The captain thinks he spots a whale off the portside. The engine hasn’t missed a beat.

Two and a half hours after leaving Wales, Douglas Coastguard gives us permission to dock. Now all we have to worry about is getting our bikes off the rubber dinghy.

Saturday, June 2: Superbike Race, Take 1

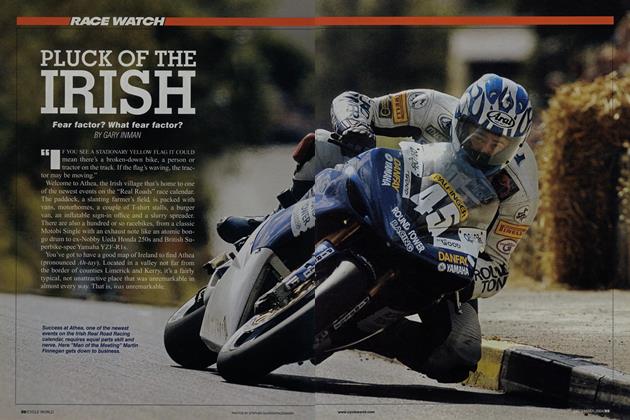

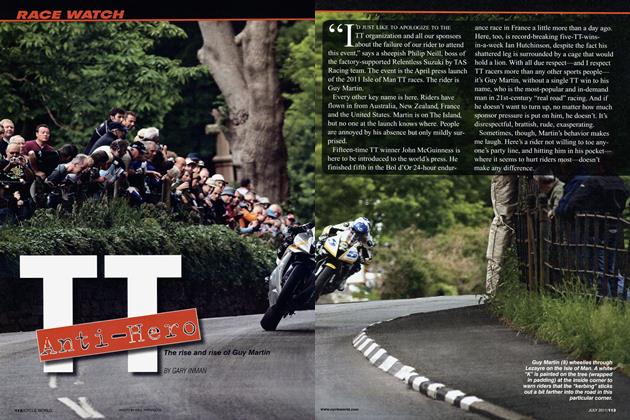

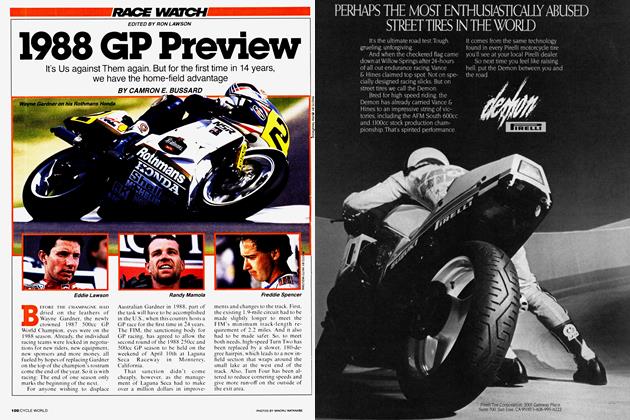

“Does it say ‘Twit’ on my forehead?” wonders my friend Guy Martin. “A lot of people are photographing me.” Hailing from England, the 25-year-old Martin is a lorry mechanic and motorcycle engine tuner. In just two years of racing on the Island, he has transformed himself from fast newcomer to true contender.

Last year, Martin was a chrysalis with potential, but he regards the 2006 TT as a disaster. Besides sprouting intermittent electrical problems, his Yamaha YZF-R1 leaked engine oil onto a footpeg. He finished fourth in Superstock, but with a DNF and no podiums in his other races, it wasn’t

enough. In the 12 months since, there has barely been a day that in some way wasn’t geared toward the TT. After blitzing the Ulster GP, Ireland’s last “real” roadrace, the Lincolnshire rider is now a nuclear-powered TT butterfly with winning the only thing on his one-track mind.

A conga line of men and machines snakes down Glencrutchery Road. The numbers on the front of the bikes don’t refer to championship positions.

Riders and teams have picked their starting positions. Former TT winner Michael Rutter is off first, hot favorite John McGuinness is third and our man Martin is eighth.

Martin looks different than the last time I saw him on the mainland just a few weeks ago. He’s taller, leaner, broader. Like something’s possessed him, pumped him up, expelled any weakness and filled the gaps with high-tensile steel.

The Vikings believed their warriors became possessed by the spirits of animals before going into battle, that they could even

change shape. I almost believe it. In a lineup of the most fearless racers on Earth, Martin looks awesome.

The start time has been pushed back again and again. Now, 2 minutes before the rescheduled sendoff, the race is postponed for 48 hours. Visibility’s bad on the mountain, and rain is coming. Rather than run

a shortened race or, more importantly, risk lives, officials say we’ll have to wait for Monday.

“I’d have raced,” says Martin, “but it was the right decision. If anyone had gotten hurt, everyone would have said the race should never have been run.”

Sunday, June 3: Eccentricity

Mad Sunday and the organizers’ prayers may have been answered. In the sun, the Isle of Man is beautiful. In the rain, it’s

more depressing than a prison exercise yard. Fly and I take the 125s for a lap of the course with the rest of the crazies. But as we come off the mountain, the fog is so thick that we’re virtually riding blind.

Weather permitting, when the flag drops on the big Senior TT next Friday, 51-year-old Steve Linsdell will have started 75 TT races. He’s the oldest participant this year. He wanted to race at the Centenary on something memorable and managed to convince the organizers to let him compete on a 500cc Grand Prix twostroke against Superbike-spec machines in the Senior event. Once he got the okay, he convinced his friends at Paton to let him borrow their bike. And supply a team to run it.

Paton is a family business based near Milan, Italy. As a manufacturer, it scored points in GPs as early as 1966 and competed from 1975, allegedly without interruption, until 2001. That was when the new four-stroke rule and the associated expense forced them to concentrate on a brand-new classic racer (an oxymoron, I know, but they make spec vintage racers from scratch). Linsdell and his son Ollie normally race air-cooled, four-stroke 500cc Paton Twins, but Steve wanted one of the strokers that lined up on the same grid, albeit at the rear, as Valentino Rossi, Max Biaggi and Loris Capirossi back in 2000.

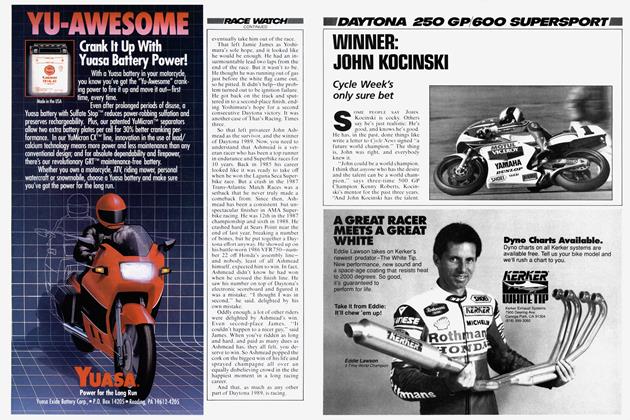

Amazingly, everyone agreed, and the bike that turned up behind the TT Grandstand is the PG500RC, the most wonderful GP mongrel. The frame and swingarm are modified 1993 Cagiva C593, as raced by John Kocinski, Doug Chandler and Mat Mladin. It is the only two-stroke Paton that doesn’t have a Paton frame.

The engine is Paton, built with a keen

recycler’s ingenuity. It is a 70-degree V-Four, with a big-bang firing order. The cases are sandcast magnesium. Barrels are Swissauto while the bores house Honda RS125 pistons that have had their crowns turned off in a lathe. Ignition and ECU are by Walbro.

Roberto Pattoni, the son of one of the company founders and chief mechanic for the TT effort, tells a story about when Paton was competing in GPs. At the time, the then-boss of HRC, Youichi Oguma, was interviewed and said, “Everyone should have a passion like Paton. I would

like to help them if I could.” Paton didn’t need a second invitation and said, “If you’d like to help us, you could sell us some of those top-secret magnesiumbodied Keihin carburetors your NSR runs so well on.” In 1993, those carbs cost $25,000 for a set of four. “They cost that much because they didn’t want anyone to buy them,” says Pattoni. A week later, a box arrived from Japan with three sets of carbs, free of charge. One bank of four is on this bike.

It has taken a gargantuan effort on the part of Paton and its TT-obsessed financial backer, Giovanni Cabbasi, to bring a retired 500 to the TT to race, not to just parade around. And Pattoni’s respect for the man riding it is complete. “I don’t know a rider in the world who would take a 500 GP two-stroke down Bray Hill on his first-ever time on the bike,” he says.

Monday, June 4: Superbike Race, Take 2

Martin catches the eye of Irish roadracing star Ryan Farquhar. “Are you nervous, boy?” asks the quiet Ulsterman. “No,” mouths Martin with a broad smile.

A minute later, Martin is introduced to the mayor. Then he climbs on his bike

for the Superbike race-what used to be Formula One. He might not feel any tension, but the adrenaline build-up is turning him into a fizz bomb of nervous energy. His booted feet tap rapidly on the lightweight rearsets.

The atmosphere is leagues apart from MotoGP or British Superbike. Mechanics munch on sandwiches. Way down the

order, Kiwi Daniel Jansen sits on the curb rhythmically sweeping his hand from side to side visualizing some of the sections he’s about to hammer through with the throttle pinned on his tired-looking Kawasaki ZX-1 OR. The riders went through all this two days ago. Weekend trippers and charter flights full of corporate guests disappeared this morning having not seen

a single lap of competition.

There are more delays today. Low cloud cover on the mountain needs time to clear. A chalkboard is carried along the grid, and officials shout out to every rider to read it. It warns of damp patches at half a dozen points on the circuit. Most bikes are wearing slicks. Two marshals scatter oil dry atop a patch of lubricant at the entrance to pit lane.

At 1:45 p.m., Michael Rutter’s green ZX-10R clunks into gear. A white-coated start-line marshal puts his hand on the rider’s right shoulder, and both men look at the small Manx flag in the hand of the starter. This light touch is the last human contact the riders will have until the race is completed. For too many riders over the past 100 years, it was their final human contact. With less fuss than some street riders make leaving a gas station, Rutter accelerates into the distance. The race is underway.

Crowds of glad-handers, press-room swindlers and camera-toting well-wishers line the start. They can stand there until the last bike rolls off. The 10 seconds between each launch must feel like an eternity when you’re holding a 1 OOOcc Superbike on the clutch knowing what

comes next-226 of the hardest miles in roadracing.

I crane my neck to see Martin leave and say a prayer I don’t really believe in. For the next 1 hour and 48 minutes, I leapfrog from vantage point to vantage point, down Bray Hill, staying within a jog of the pit lane so I can get back to see Mar-

tin if he wins. At the bottom of this residential road, he is clocked at 193 mph.

I watch the first pit stop, and he comes in three-abreast with HM Plant’s Ian Hutchinson and Martin Finnegan. Martin has made up some time. The wheel change is brilliant, but the fueling could be better. His crew is made up of British

Superbike mechanics not used to pit stops.

The scene that lines the track is beautiful. Churches sell homemade cakes to raise funds. Beautiful women with campsite hair sun themselves in vests and leather trousers. Kids and their moms play on picnic blankets. Stone walls are three deep with everyone else watching the race and gasping as young Michael Dunlop (yes, that Dunlop) experiences an evil speed wobble over the brow near the grandstand.

As each bike passes, it’s followed by a wake of dry leaves doing a three-story dance down the hill. McGuinness arrows past, followed by a wave of applause that’s followed him from Ramsey. Martin comes in a minute and a half later-26 seconds adrift on corrected time. That’s 26 seconds after 108 minutes of racing. Martin is excited, spitting heavily accented crowdpleasers into TV and radio microphones. It’s not until the national anthem is played 10 minutes later that he begins to look disappointed.

“I caught Ian Lougher quickly, but I didn’t listen to McCallen,” says Martin, talking about the mentoring he received from one of the all-time-hardest TT racers, Phillip McCallen. “He said as soon as

you catch someone, pass them, but I didn’t. I sat there for what seemed like an eternity. I lost my rhythm. Then I caught Finnegan and had to shout at him at the hairpin, ‘Get out of the way!’ He sat up. You would, too, if you heard someone screaming at you.

“And I didn’t push hard enough on the first lap because I thought John would

take it easy in the damp and not stick his neck out. But I’m only a bairn (baby). I have a lot to learn.”

Tuesday, June 5: Dunlop Garage I’ve been to the TT four times in the past 15 years, and I was still under the impression that per the legend, racers took their bikes back to residential garages to

work on them. But factory team trucks have invaded Nobles Park. In fact, there’s only one high-profile name still working out of the back of a van, still wrenching in the garage of a rented house, and that name is Dunlop.

Robert Dunlop draws a map to the house on my notepad. Around back, a double garage is open. On a bench outside sits

the Aprilia 125 that Robert is riding in the parade. Inside, son Michael is working on his Yamaha R1 Superbike.

At 19, Michael is the youngest-ever TT competitor. He finished 25th out of 70 starters in his first race. His brother William is also racing, but he’s up in the paddock at the moment. Sometimes it’s hard to get away when everyone wants to buy your dad a drink.

On a shelf is a pink-and-white plaster cast, the fluffy ends so clean it can’t have been on long. “That belongs to William,” says Michael. “He crashed at Cookstown. We cut it off so he could race his 600.” Michael has the gas tank and seat off now. He sees a kinked breather pipe. “I’ll fix this,” he says, “and take her up the road down there to see if it’s better.”

The road “down there” is open to the public. The bike is wearing putty-like

slicks and open race cans. But no one will mind. He’s Robert’s boy.

Wednesday, June 6: Superstock Race

After another night in a shed in Laxey, we ride to Ramsey to watch a bit of the seafront sprinting (Brit-speak for drag racing). Time slips by, and when I ask someone what time the Superstock race starts, he says, “Ten minutes ago.” They’re four deep at Parliament Square by the time I arrive. It’s like watching a football match through a letterbox.

Bruce Anstey barrels through on the black Relentless Suzuki. Even from my 6-second snapshot, it’s obvious he’s in the lead. I see the top 10 come through, but I don’t spot Martin. I ask someone with a radio what’s happened. “Don’t know,” he tells me. “I couldn’t get any reception.” I wait until someone with a bigger radio walks past. “He ran out of fuel,” he explains. “So did Farquhar.”

Running out of fuel before the pit stop? That’s an inexcusable mistake, I think. Martin later tells me a faulty ECU was chucking fuel down the bores-nothing to do with tank capacity. Still, it isn’t stopping the team from enlisting Martin’s dad

Ian to beat every possible indentation out of the Honda CBRóOORR’s tank for tomorrow’s Supersport race.

Meanwhile, Fly and I book a ferry home. We planned to take the dinghy back, but the motor was dribbling a brown excretion of emulsified oil. The captain and Easty left on Tuesday evening and broke down three miles short of home when the motor cut out and wouldn’t restart. They eventually limped into port, but what would have happened if the RIB had been carrying three times the load?

Our final evening is filled with banter in the company of Martin and his team, watching the RAF Red Arrows perform over Douglas and another night in the Laxey shed. Tomorrow, we’ll leave the Isle of Man stuffed rudely into the gunwales of the slow boat to Heysham. We came by dinghy and didn’t have a single night’s accommodation booked. We slept in sheds, under hospitality awnings and in a truck. We met the coolest, most welladjusted racers on the planet, enthusiasts from five continents, crackpot engineers and genius mechanics. In the summer of 2007, if you love racing motorcycles, there was only one show in town. Next year, the TT will be 101 years old. Book now to avoid disappointment. □

For additional photography from "The TT Centenary," go to www.cycleworld.com