SCOOTERS FROM HELL

RACE WATCH

The riders of the American Scooter Racing Association prove that Mods rock!

BRIAN CATTERSON

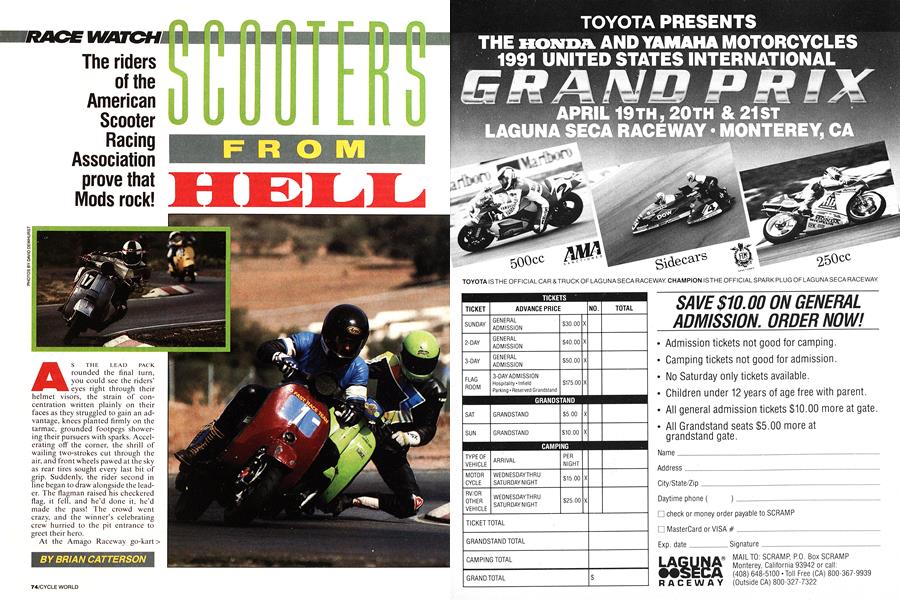

AS THE LEAD PACK rounded the final turn, you could see the riders’ eyes right through their helmet visors, the strain of concentration written plainly on their faces as they struggled to gain an advantage, knees planted firmly on the tarmac, grounded footpegs showering their pursuers with sparks. Accelerating off the corner, the shrill of wailing two-strokes cut through the air, and front wheels pawed at the sky as rear tires sought every last bit of grip. Suddenly, the rider second in line began to draw alongside the leader. The flagman raised his checkered flag, it fell, and he'd done it, he'd made the pass! The crowd went crazy, and the winner’s celebrating crew hurried to the pit entrance to greet their hero.

At the Amago Raceway go-kart > track, that’s a very short walk.

CONTINUED

The Cycle World staff was here not for some top-secret pre-season test session, nor to put the latest crop of sporting hardware through its paces, but to meet a group of fellows whose common interest lies, well, a little wide of the normal scope of this magazine—or motorcycling in general, for that matter. These were scooter racers—that’s right, scooters, those homely little motorized contraptions most often seen chained to bicycle racks at college campuses. And as we watched the fearless warriors astride their 10-inch-wheeled, step-through steeds clicking off one 40-second lap after another, we found ourselves> with just one burning question: Why?

CONTINUED

Ask a mountain climber why he does what he does and he’ll tell you, “Because it's there.” Ask a group of scooter racers the same question, and the answer could be anything: a history lesson, a technical briefing, a lecture on style, a simple shrug of the shoulders. But ask that same group how they got into their hobby, and it’s as if they’d rehearsed their replies, as one American Scooter Racing Association member after another replays the familiar story of a street rider gone roadracing. Tired of risking life and license tearing up the canyons, these wanna-be racers sought solace on the track, away from the inherent hazards of daily traffic, and out of reach of the long arm of the law.

The first scooter race in Southern California was held in 1985, but it was two years before there was another. The years 1987-88 saw sporadie action, but in 1989, the ASRA was formed, and since then there have been a half-dozen or so races per season, split between Amago Raceway, Adams Kart Track and The Streets of Willow Springs.

What's truly interesting about these guys, however, is not simply that they race scooters, but how they came to be involved in scooters— more importantly, high-performance scooters—in the first place. Although the dozen riders in attendance ranged from 19 to 29 years old, they're all graduates of a subculture transplanted from 1960's England—The Mods and The Rockers, as popularized by The Who’s album Quadrophenia. The Mods rode scooters, the Rockers rode cafe bikes (see “Return of the Rockers," CW, November, 1990), and as it turns out, there existed a quite-popular Mods scene in Los Angeles, San Diego and San Francisco in the early '80s. Clubs such as the Nightstalkers and the Scooter Boys were populated by kids who were barely out of diapers during the original Mods 'n' Rockers era. and together these riders took to the streets on customized scooters, clad in outlandish, wildly colored, zebrastriped outfits.

But some Mods wanted more out of life than to profile down the bou> levareis. Like Steve Cocking, a 23year-old San Diegan, who recalls, “I got tired of roaming the streets in packs, and seeing who could bolt the most mirrors onto his bike.”

CONTINUED

Cocking wasn’t alone in his feelings, and soon he, his younger brother Scott, and others had formed a club called BLURR, devoted exclusively to high-performance scooter> riding. Club members dressed in allout roadracing garb, and they began to get truly serious about modifying their mounts.

CONTINUED

There’s a problem with that, however, as 22-year-old Curtice Thom told us: “You can’t just go to Yoshimura and buy scooter parts,” he says.

If you want a trick scooter, you have to build it yourself. Given that Italian-made Vespas and Lambrettas are the machines of choice, this is not an easy task, and as a rule, scooter racers are as adept with their tools as any motorcycle roadracing tuner.

With design roots tracing back to the need for cheap transportation following World War II, Vespas and Lambrettas are primitive in construction, and surprisingly similar, with a number of inherent design flaws. Most notable is a distinctly rearward weight bias, thanks to the engine, the fuel tank and the rider being placed just ahead of and atop the rear wheel. At the speeds these guys attain, this results in a tendency to push the front end, particularly while exiting corners with the power on, where even the slowest scooters will try to wheelie and steer off the edge of the track. Another shortcoming is the lack of torsional rigidity of their stepthrough chassis, which allows them to flex during hard cornering—the proverbial hinge-in-the-middle handling bugaboo.

Naturally, these problems have been addressed by the scooter racers, with modifications ranging from welding support tubes across the foot tray to replacing the frame alto-> gether. One racer, 24-year-old reigning club champ Matt Dawson, even went so far as to build an aluminum monocoque chassis, incorporating

CONTINUED

Amago Raceway, located on the La Jolla Indian Reservation in northern San Diego County, is a popular practice track, but is considered too slow for proper scooter racing. At faster tracks, modified scooters nudge 100 mph.

the fuel tank as an integral part of the frame.

Why go to all that trouble when you can get the same thrills out of a virtually race-ready YSR50, Yamaha’s popular GP-styled pocket rocket, and do so for a lot less money? “Bolting parts onto a YSR isn’t my idea of fun,” Dawson says, with a laugh. “That may be state-ofthe-art, but we’re starting lower, and having to design things ourselves to find an edge. That’s more in keeping with the true spirit of racing, I think.”

In the early days of scooter racing, classes were structured by displacement only and, as ASRA founder Vince Mross admits, “The bikes started looking less like scooters and more like motorcycles.” Highly modified, they were expensive to build and maintain, and before long, the less fortunate racers became discouraged and entries dropped.

So a rules committee was formed, and the result was the addition of stock classes to offer affordable racing to the masses. However, the masses have yet to take notice, and slim entries continue to be the single largest hurdle the club faces. This is a problem not only in generating revenue to keep the organization run-> ning, but in obtaining race dates, due to the high cost of track rentals. As a result, entry fees are high: A rider’s first entry costs $80, though if he wishes to compete in more than one class during a race weekend, subsequent entries are discounted.

CONTINUED

ASRA rules mandate use of the stock engine cases and a scooter-type fork in all classes, but in the modified classes, just about anything else is fair game. The rules prohibit adapting the cylinder from, say, a Japanese motocrosser onto a scooter’s cases, but if you want to make your own cylinder, that’s fine. Bolting the cylinder head from a dirtbike onto a Vespa or Lambretta is also perfectly legal; Mross even machined his own liquid-cooled head. Specialty shops such as Mross’ West Coast Lambretta Works and Fabio Ballarin’s Vespa Supershop, both located in San Diego, will be happy to sell you a kit to convert your rotary-valve Vespa or piston-port Lambretta to reed-valve induction, to replace your pointsand-condenser ignition with an electronic unit, to alter your stroke or to increase your bore, but most everything else is up to you.

Popular chassis modifications include replacing the stock front dampers with sportbike-style steering dampers, and adding fuel tanks, seats and fairings from a Suzuki GSXR50, Yamaha YSR-50 or TZ125.

Reto-fitting parts from newer models onto older ones is worthwhile, as is upgrading the smaller-displacement (125cc) models with parts from the larger ones.

Where on Earth do you find raceready rubber for 10-inch wheels? It’s not as much of a problem as you’d imagine, as Bridgestone, Dunlop, IRC and Michelin all make excellent treaded tires. Slicks are available, but aren’t popular at the slow go-kart tracks because they’re reluctant to heat up.

Spend enough time and money on one of the larger-displacement (220cc-plus) Vespas or Lambrettas, and you'll be rewarded with a bike producing about 30 horsepowerthree times that of a stocker.

“We’ve taken something designed to go to the grocery store and made them go 100 mph,” says Chito Cajayon, 25, of Long Beach. “We could have applied what we’ve learned to normal motorcycles, but they just don’t have the style. That’s what it’s about: speed and style.”

Say what you will about these scooter racers, but you have to admire them for their ingenuity in creating what can only be called unique racing vehicles, and for holding dear that one aspect of motor racing that all too many motorcycle racers seem to forget: It’s supposed to be fun.

No matter what size your wheels.ES

CONTINUED

Clipboard

Peterhansel wins ParisDakar Rally

J^renchman Stephane Peterhansel, 25, can now add a win in the ParisDakar Rally to his list of accomplishments, which also includes winning the ISDE twice and placing second to Wayne Rainey in the I 990 Guidon d’Or, a Superbikers-style contest.

Despite nursing an injured shoulderblade, despite getting lost, despite melted innertubes, a lost compass, a collapsed rear shock and no rear brake, Peterhansel, riding a Sonauto Yamaha Super Ténéré Twin, held off the challenges of two fellow countrymen to take the win in what is surely one of the most grueling motorsport events on Earth.

Pursuing Peterhansel across the finish line were Chesterfield Yamaha rider Gilles Lalay and Peterhansel’s Sonauto Yamaha teammate Thierry Magnaldi, who finished a close second and third. In fact, the three riders ran nose-to-tail at the finish, but corrected time gave the win to Peterhansel by 16 minutes, 55 seconds. >

CONTINUED

Two riders who showed promise before crashing out of the event were American Danny LaPorte and Italian Alessandro de Petri. LaPorte, 34, the 1982 250cc MX World Champion and a two-time Baja 1000 winner, was a frontrunner on his Sonauto Yamaha before crashing at high speed in Niger, knocking himself out of the race and into the hospital with a concussion. LaPorte was flown by helicopter to a hospital in Agadez, and then transferred to one in Paris where he was treated and released.

De Petri was blazingly fast in the desert on his Chesterfield Yamaha, but mechanical problems and an eventual broken collarbone conspired to halt his charge.

This year’s Paris-Dakar Rally, which covered 5700 miles, passed through six countries and took two weeks to complete, re-emphasized its tough reputation as just 41 of the 1 1 3 motorcyclists who started the race were able to finish.

Rent row hurt

fîoadracing veteran Randy Renfrow, 34, suffered careerthreatening injuries as the result of a pre-season test-session accident at Southern California’s Willow Springs International Raceway. The Virginian crashed his Commonwealth Honda RC30 Superbike in the notorious, flat-out Turn Eight and caught his right hand under the bike, doing extensive damage. Doctors amputated his thumb following the incident, in which he also lost the tips of his index and middle fingers, and skin grafts were performed to save the tip of his ring finger. Plans now call for removing one of Renfrow’s toes and attaching it to his hand to replace his thumb; if the operation is successful, Renfrow says he’ll be back on a bike next season.

CONTINUED

With his number-one rider sidelined. team owner and manager Martin Adams has signed Miguel DuHamel, son of Canadian roadracing legend Y von DuHamel. to join Richard Arnaiz on the Commonwealth Honda squad. Both riders have one AMA Superbike win to their credit.

In an additional twist, the team has secured sponsorship from Camel cigarettes for three of this season’s nine rounds. Though R.J. Reynolds has a long history of supporting motorcycle racing through its Camel Pro Series, this is just the second time the company has sponsored an individual; the first was when it backed Bubba Shobert in the 1988 25()cc United States Grand Prix.

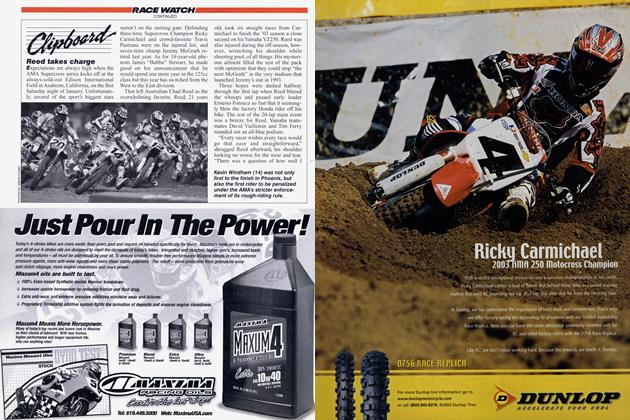

Bayle on a roll in Supercross

French factory Honda rider JeanMichel Bayle, 2 l, has taken control of the AMA Camel Supercross Series with wins in three of the six rounds to date. After cruising to a second-place finish behind > teammate JefTStanton at the opening round of the series in Orlando, Florida, Bayle moved into the points lead for the first time when he won the next round at the Houston Astrodome, taking full advantage when Stanton crashed. The following week, in Anaheim, California. Bayle got a bad start and finished fifth while Stanton won, returning the Michigan native to the top of the standings.

CONTINUED

But Bayle retaliated at the Seattle Kingdome, where he put the hurt on local favorite Larry Ward to claim his second win, and reclaimed the series point lead. A week later in San Diego, Bayle won his third race of the season, further solidifying his advantage. With a second-place finish behind Team Yamaha’s Damon Bradshaw at the most recent round in Atlanta, Georgia, Bayle still has a secure grasp on the point lead. Bayle, the 1989 250cc World Champion now leads Stanton, the two-time and defending Supercross champ, while Bradshaw lies third.

Meanwhile, in 125cc action,

Brian Swink continues to lead the Eastern Regional standings with two wins in the three rounds run to date, while Jeremy McGrath leads the Western Region with wins in all three rounds to date. 13

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontDeath of the Fork?

May 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeTalking Hats

May 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

May 1991 -

Roundup

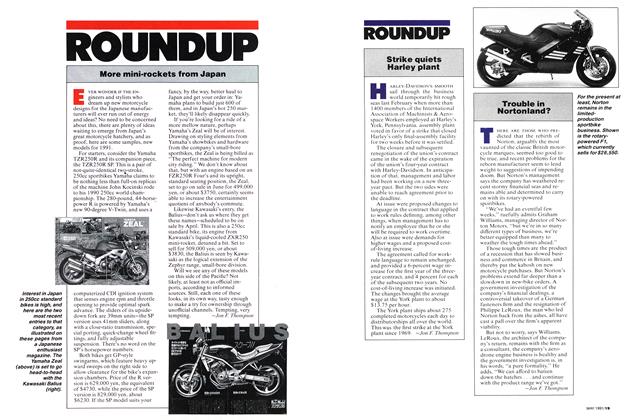

RoundupMore Mini-Rockets From Japan

May 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupStrike Quiets Harley Plant

May 1991 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupTrouble In Nortonland?

May 1991 By Jon F. Thompson