Clipboard

RACE WATCH

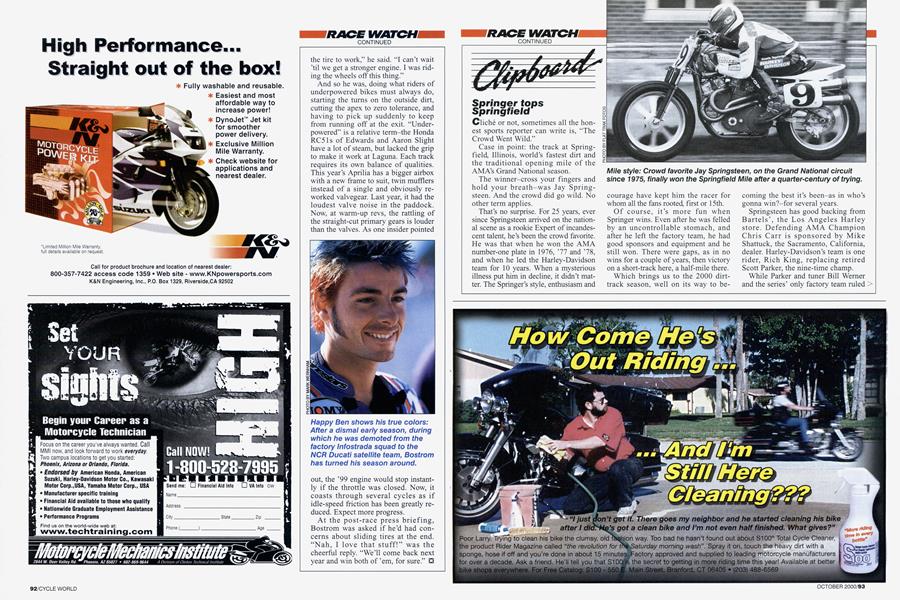

Springer tops Springfield

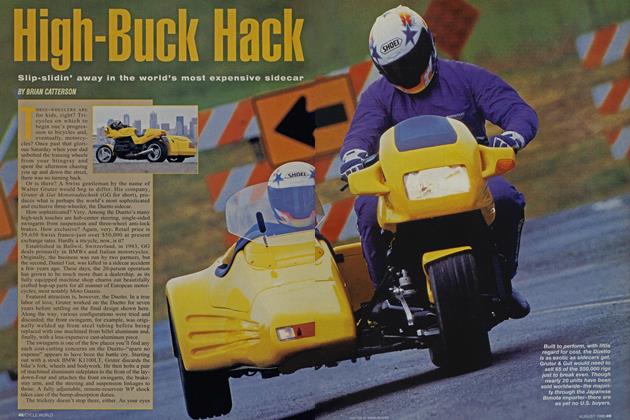

Cliché or not, sometimes all the honest sports reporter can write is, "The Crowd Went Wild."

Case in point: the track at Springfield, Illinois, world's fastest dirt and the traditional opening mile of the AMA's Grand National season.

The winner-cross your fingers and hold your breath-was Jay Springsteen. And the crowd did go wild. No other term applies.

That’s no surprise. For 25 years, ever since Springsteen arrived on the national scene as a rookie Expert of incandescent talent, he’s been the crowd favorite. He was that when he won the AMA number-one plate in 1976, ’77 and ’78, and when he led the Harley-Davidson team for 10 years. When a mysterious illness put him in decline, it didn’t matter. The Springer’s style, enthusiasm and courage have kept him the racer for whom all the fans rooted, first or 15th.

Of course, it’s more fun when Springer wins. Even after he was felled by an uncontrollable stomach, and after he left the factory team, he had good sponsors and equipment and he still won. There were gaps, as in no wins for a couple of years, then victory on a short-track here, a half-mile there.

Which brings us to the 2000 dirttrack season, well on its way to be-

coming the best it’s been-as in who’s gonna win?-for several years.

Springsteen has good backing from Bartels’, the Los Angeles Harley store. Defending AMA Champion Chris Carr is sponsored by Mike Shattuck, the Sacramento, California, dealer. Harley-Davidson’s team is one rider, Rich King, replacing retired Scott Parker, the nine-time champ.

While Parker and tuner Bill Werner and the series’ only factory team ruled the roost, so to speak, for 10 years, now the playing field has been leveled.

Plus, there are more fields in which to play. The PACE dirt-track series, created because that marketing firm, the owners of the immensely popular (and profitable) Supercross series, saw dirt as pay dirt, is also off to a promising start.

Not only that, the AMA and PACE (unlike the four-wheel groups) have been careful not to cross the lines each has drawn. The schedules are designed not to conflict. The rules are compatible: The AMA races are run with 750cc Twins for mile and half-mile, 600cc Singles for TT and short-track. PACE uses a complicated formula designed to let 600cc Singles and 750cc Twins compete on the same track. This means a team can use the same bikes in both series, equipped and tuned for the course-try that in the IRL and CART.

PACE is investing money in their program, with generous purses, new tracks and promotion. As a result, the top riders are appearing in both series:

At one early stage, Carr was first in the AMA standings and Will Davis was fourth, while Davis led the PACE contest and Carr was fourth. Both sanctioning bodies can promote Springsteen, Carr, King and Davis in the ads, and both have national backing, which may make it worthwhile for the sports reporter to wade through the full titles, as in Progressive Insurance U.S. Flat Track Championship for the AMA vs. Wrenchhead.com National Dirt Track Series for PACE.

With twice as many races, there’s more money, enough to allow the established Pros like Springsteen and Terry Poovey, winner of the AMA Daytona Short-Track, to field a full program. There’s twice as much money to be won and twice as much exposure for the sponsors.

As perhaps a surprising bonus, considering that both groups like to call themselves “national,” the doubling of the events and the need for more tracks has literally widened the field while it was being leveled.

From the AMA’s events in Florida, New York and Michigan to the PACEbacked races in Washington, Oregon and California, for the first time in years we are seeing races coast to coast and border to border. (Okay, thanks to New Hampshire International Speedway having replaced the old dirt-to-pavement circuit in Belknap Park, there are no national dirt races in New England. Even so...)

And not least, the doubled fields also have depth. At this writing, Carr is the only rider who’s won more than one race, or won a race in both series.

Any thorns in all these roses? Perhaps. While both groups have been generous with the main events, the opening acts, so to speak, have been thin on the ground. Sometimes the AMA races will have a semi-Pro class for Singles or dirt-prepped Sportsters, but more often they do not. And PACE usually offers a Pro class for 600cc Singles.

The salvation-the extra push to make dirt-track as popular as it should be-is, of course, the SuperTrackers class.

The bad news is that only seven of the AMA nationals will offer that class, presumably because last year all the races were won by Suzukis, that brand having made the most effort.

The good news is that this year, the first two SuperTracker events were won by...a Buell. Yes. Okay, Mike Hacker’s mount is a Buell 1200 engine in a dirttrack frame, but even so, the Lima, Ohio, round was composed of two Buells, nine Suzukis and two Harleys, so if brand rivalry is what it takes to attract a crowd, the SuperTracker series has it.

Meanwhile, the parallel, head-tohead 2000 season is the best dirttrack year since... well, since the last time “Springer” brought the crowd to its feet.

Allan Girdler

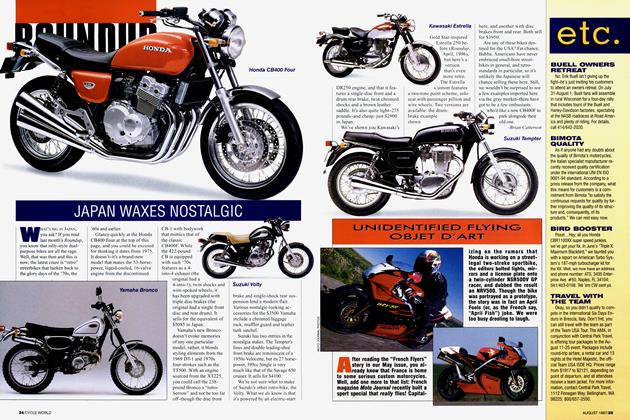

Bad-boy Gobert and the Modenas equation

Does size matter? Kenny Roberts Senior might think so. Particularly where Anthony Gobert is concerned. The Australian’s riding skill is not in question, especially in tricky half-wet conditions. Nor his familiarity with Dunlop tires. But there’s one over-riding problem with his 500cc Grand Prix return aboard the renascent three-cylinder Modenas for Roberts’ England-based team: size.

“We can’t make a bigger motorcycle. Or a smaller rider,” said Roberts after a race for which Gobert had qualified a disappointing 20th-second from last-and finished 15th in spite of the sort of half-wet track where the Triple’s nimble handling might have paid dividends.

Hiring bad-boy Gobert was the latest in a series of increasingly desperate moves by Roberts to keep his beleaguered, independent GP-bike project alive. Bullish when he came away from years of hand-in-glove with Yamaha to challenge the Japanese factories head-on, the three-time 500cc Champion remains as sure now of the need for an alternative motorcycle, and the value of his three-cylinder approach. From the start, however, Roberts and the Modenas KR3 have been ambushed by circumstances.

The biggest problem has been the relentless racing time-scale. The first Modenas KR3 was built just in time for the 1997 season. Shake-down tests took place during qualifying sessions and races; teething troubles were embarrassingly public.

These came mainly from over-ambitious detail engineering. Ducted cooling to a rear-mounted radiator decreased frontal area but led to overheating. Dispensing with one main bearing so two of the three cylinders shared a crankcase made a compact motor, but gave rise to vibration so destructive that the fuel frothed, bolts came undone and fittings fractured. Homemade electronic carburetors added another imponderable to the development equation.

The Mk.2 bike was finished late in 1998. This restored the missing main bearing, added a balance-shaft to kill vibration, put the radiator up front and used Keihin carbs. Reliability came along with the changes, but the Mk.2 was heavier and longer.

After two years of poor results, chief sponsor Marlboro cried enough, and switched back to Yamaha. The riders were also tired of losing the game. Kenny Roberts Junior moved to Suzuki to start winning races; Ralf Waldmann went gladly back to the 250cc class. The two designers also went-Warren Willing with Junior, and Mike Sinclair back to Yamaha.

Roberts saw out another year, struggling for riders after injured Frenchman Jean-Michel Bayle retired mid-1999. He retained the support of his Malaysian backers, who had given the bike the Modenas name (Modenas makes commuter bikes) as well as the valuable technical backing of the holding company, Proton cars. At the same time, the need for an alternative to the expensive Japanese bikes grew more acute as fellow constructors Swissauto and New Zealand’s BSL pulled out at the end of last year. Nothing if not stubborn, Roberts vowed to see the Mk.3 through to the racetracks, with or without major backing.

This third bike combines the nimble handling and compact size of the Mk.l with the power and reliability of the Mk.2. The balance shaft was moved up and the gearbox forward to save 50mm in engine length, while most engine components, including the crankshaft and cylinders, were retained. But in spite of the skeleton staff’s best efforts, the new bike wasn’t even running until the fifth round in France, where it broke crankshafts in practice. It had clutch problems at Mugello, Italy, but has finished the three races since then in the points, including an impressive eighth in the rain at Barcelona, Spain.

Until the British GP at Donington Park, old and new bikes were ridden by Spanish 22-year-old David de Gea, a relative GP novice who always tried hard and never fell off. But Roberts needed an experienced rider to accelerate development and attract vital sponsorship for next season.

His first choice was veteran Luca Cadalora, 125 and 250cc Champion and 500cc GP winner, who has tested the new bike twice. “It is good, but needs lots of small things improved,” he said. “I have given the team a list.” Cadalora was the first choice for Donington. He declined, however, and Gobert-unexpectedly free after the collapse of his Bimota Superbike team-got the nod instead.

In his first ride on a 500 since being fired by Suzuki for failing a drug test in 1997, Gobert aimed for a measured return. “I don’t want to kill the world, or kill myself,” he said. “I want to pick up speed gradually, and hopefully I’ll get another chance to ride the bike.” Roberts’ remarks on the problems with Gobert’s size-not to mention his openly admitted preference for Cadalora-make this doubtful.

Which denies us the spectacle of seeing whether noted hard man Roberts would be the one finally to knock the rough edges off fast-butwild Gobert. -Michael Scott

Nevada 2000, still no easy task

The longest off-road race in America came back for an encore, and if early reports are indeed reliable, look for another repeat soon.

As part of the new millennium, Best in the Desert Series organizer Casey Folks envisaged an extravaganza similar to the Acerbis Adventures Nevada Rally, which ran from ’93-95, and took its participants on a tour around the Silver State in a European rally format.

This time, however, it’d be an allAmerican desert race-with a twist. It would include six consecutive days of racing, with each day’s time on course counting (plus any time penalties) toward a cumulative time to determine overall finishers.

That suited Honda’s Johnny Campbell just fine. As the last winner of the Nevada Rally after Frenchman Alain Olivier won the first two, Campbell has blossomed into perhaps the finest longdistance off-road racer in America.

But he and partner Tim Staab first had to deal with six days of speeding along Nevada’s dirt roads faster than guys like Honda teammates Steve Hengeveld and Jonah Street; Kawasaki’s pair of front-running teams, Destry Abbott/Brian Brown and Shane Esposito/David Ondas; plus the Yamaha YZ426F-mounted duo of Ty Davis and Russell Pearson.

“The difference between this event and the rally is we get a teammate,” Campbell explained. “The other major point is that there’s no road-book navigation. Instead, we’ve got to follow course markers and stick to the course rather than feeling our way through.”

But since it boiled down to six days of desert racing, it was no real surprise that Abbott and Brown immediately went to the front. They are, after all, numbers two and one, respectively, in the AMA National Hare & Hound Series, and this year Abbott has been nearly unbeatable in that series.

“We’ve got a couple minutes lead after the first day,” Abbott noted while resting in Mesquite, day one’s destination. “We’re just going to go out front and cruise. Now, it’s basically just trying to keep the bike together. Brian and I feel like we’re capable of winning this thing as long as our bike stays together.

“It’s going to be interesting, though,” he continued. “It’s six days long, and anything can happen.

I mean, two teams are already out-two of the teams that were going to be a threat. We’ll see what happens. Brian and I have both ridden the International Six Days Enduro. Hopefully the experience will help.”

The race quickly developed into a three-horse battle between Abbott and Brown, Campbell and Staab, and Hengeveld and Street, with the raceproven-if-somewhat-dated KX500 leading the new XR650Rs day after day after day. Abbott and Brown enjoyed smooth sailing, and their bike ran reliably as the miles passed, though they admitted it was no cakewalk.

“We’re not riding at 50 or 60 percent; we’re having to ride pretty> hard,” Abbott said.

Staab revealed his team’s plan, saying, “Our strategy right now is to go as fast as we can. We know our bike is really reliable; it’s going to make it no matter what, so we just want to go mistake-free. Hopefully in the end, it’ll pay off.”

Of course, that was after finishing day three. Staab did an awkward flip and broke his foot near the end of day four, prematurely ending his week (though he did make it to the finish that day) and leaving Campbell to fend for himself. To make matters worse, Campbell, Staab and several others contracted the flu or food poisoning that night. So not only did Campbell have to ride the last two days alonedays that included the longest and roughest sections of the week-he’d also have to do so while feeling like racing a motorcycle was the last thing his body could do.

But then Team Honda got the break it had been waiting for all week. Some 100 miles into day five, Abbott came up short on an unintended highspeed jump with the impact resulting in a concussion when his chin hit the bike’s steering damper.

With Abbott unable to continue and the bike in need of repair, the Team Green front-runners were forced to accept a time penalty while Campbell and company sailed past and into the lead for the first time. Campbell and Staab would emerge the overall winners with a time of 25:28:57, while Hengeveld and Street backed them up at 25:41:53. KTM 300-mounted Rick Bozarth and Daryl Folks earned third overall, first Over 30 (and first twostroke) team in 26:50:44.

“You just knew it had to happen sooner or later, that they’d have some sort of dilemma,” Campbell said. “Fortunately for us, we got in the lead there on day five; it gave us a little boost of confidence coming into the last couple days. Everything worked out. Just like I said at the beginning of this thing, consistency is going to win it-and we were second place every day. That’s what it takes.”

Mark Kariya

Jamie Bowman, 1975-2000

The close-knit AMA roadracing community lost one of its own when Jamie Bowman, 25, was killed during Friday Superbike practice at Laguna Seca Raceway.

The news hit especially hard in Bowman’s native Florida, which suffered the loss of former Yoshimura Suzuki star Donald Jacks in a tragic non-racing accident just five years ago.

Bowman’s crash was peculiar in that it occurred to rider’s left in the little right-hand kink at the entrance to Laguna’s Turn 3. According to witnesses, Bowman’s Suzuki GSX-R750 started spinning its rear wheel and weaving violently exiting Turn 2, and he appeared to stay on the gas until the bike pitched him off, fueling speculation that the throttle may have stuck. His helmet struck an unprotected concrete wall, and he was airlifted to the hospital where he was later pronounced brain-dead.

Bowman burst onto the scene with a Vance & Hines Yamaha factory Supersport ride in 1993. Touted as an up-and-coming star, he instead had his season hampered by injury and was subsequently dropped from the team. In the years that followed, he became a regular top-10 finisher in the AMA 600 and 750cc Supersport classes, one of the unheralded privateers who help push the pace at the front. Bowman’s years of hard work finally were rewarded in 1998 when he won the $5000 Suzuki GSX-R750 Cup Final at Road Atlanta. Bowman landed a ride with the Hooter’s Suzuki team for ’99, notching a best result of third in the 750cc Supersport national at Loudon, New Hampshire, and then winning when the AMA circus returned to that venue this year. When he was killed just three weeks later at Laguna Seca-ironically, his favorite track-both Nicky Hayden and Troy Corser dedicated their Superbike wins to him.

I first met Jamie Bowman at a press conference introducing Yamaha’s ’93 race teams. Fittingly, the event was held at a hotel not far from Disneyland, and the soft-spoken 18-year-old had a smile befitting the Happiest Place on Earth. At 6-foot-1 and 150 pounds, he was a beanpole of a kid, an observation I again made when I ran into him at this year’s Daytona Bike Week. Three of us Cycle World editors had ridden down from Atlanta on testbikes, and were scouring the Daytona pits for a scale on which to weigh them. At the tech garage, I ran into Jamie, who was helping the PACE Motorsports crew load their truck. He unselfishly introduced me to the tech inspector, helped facilitate setting-up the already-packed scales, then went back to loading the truck. When I left in a hurry for my next practice session, I neglected to thank him.

So thanks, Jamie. For everything.

Brian Catterson

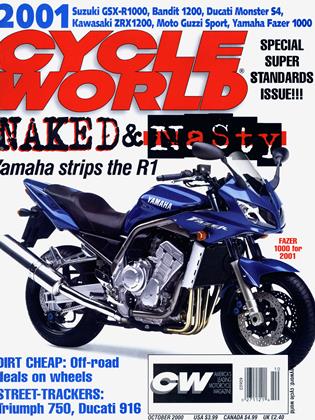

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontRally At Red Rocks

October 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsLate-Braking News

October 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCMaking It Happen

October 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

October 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupSpied! Suzuki's Big-Bore Blaster

October 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupGood-Bye, King of the Roads

October 2000 By Brian Catterson