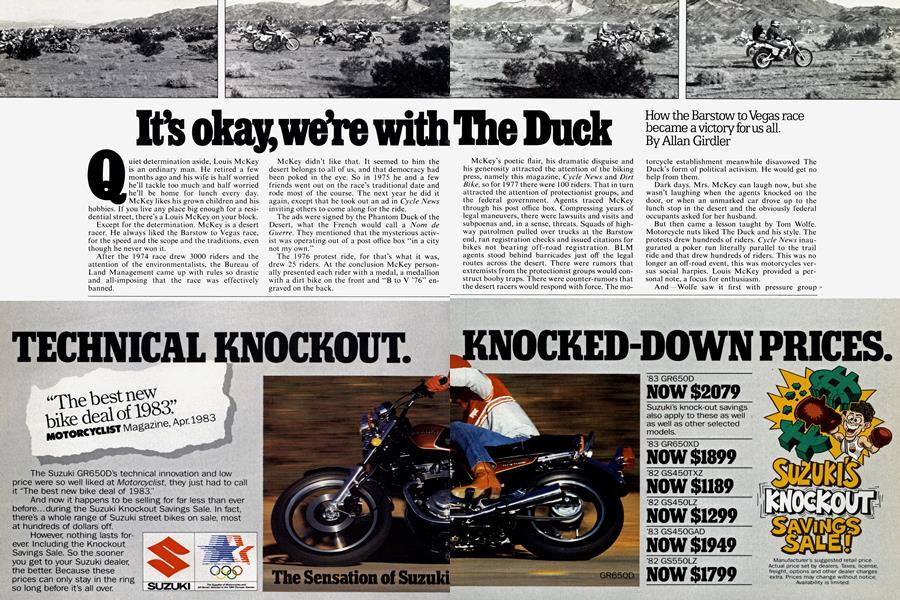

It's okay,we're with The Duck

Quiet determination aside, Louis McKey is an ordinary man. He retired a few months ago and his wife is half worried he’ll tackle too much and half worried he’ll be home for lunch every day. McKey likes his grown children and his hobbies. If you live any place big enough for a residential street, there’s a Louis McKey on your block.

Except for the determination. McKey is a desert racer. He always liked the Barstow to Vegas race, for the speed and the scope and the traditions, even though he never won it.

After the 1974 race drew 3000 riders and the attention of the environmentalists, the Bureau of Land Management came up with rules so drastic and all-imposing that the race was effectively banned.

McKey didn’t like that. It seemed to him the desert belongs to all of us, and that democracy had been poked in the eye. So in 1975 he and a few friends went out on the race’s traditional date and rode most of the course. The next year he did it again, except that he took out an ad in Cycle News inviting others to come along for the ride.

The ads were signed by the Phantom Duck of the Desert, what the French would call a Nom de Guerre. They mentioned that the mysterious activist was operating out of a post office box “in a city not my own.”

The 1976 protest ride, for that’s what it was, drew 25 riders. At the conclusion McKey personally presented each rider with a medal, a medallion with a dirt bike on the front and “B to V ’76’ graved on the back.

How the Barstow to Vegas race became a victory for us all.

Allan Girdler

McKey’s poetic flair, his dramatic disguise and his generosity attracted the attention of the biking press, namely this magazine, Cycle News and Dirt Bike, so for 1977 there were 100 riders. That in turn attracted the attention of protectionist groups, and the federal government. Agents traced McKey through his post office box. Compressing years of legal maneuvers, there were lawsuits and visits and subpoenas and, in a sense, threats. Squads of highway patrolmen pulled over trucks at the Barstow end, ran registration checks and issued citations for bikes not bearing off-road registration. BLM agents stood behind barricades just off the legal routes across the desert. There were rumors that extremists from the protectionist groups would construct booby traps. There were counter-rumors that the desert racers would respond with force. The motorcycle establishment meanwhile disavowed The Duck’s form of political activism. He would get no help from them.

Dark days. Mrs. McKey can laugh now, but she wasn’t laughing when the agents knocked on the door, or when an unmarked car drove up to the lunch stop in the desert and the obviously federal occupants asked for her husband.

But then came a lesson taught by Tom Wolfe. Motorcycle nuts liked The Duck and his style. The protests drew hundreds of riders. Cycle News inaugurated a poker run literally parallel to the trail ride and that drew hundreds of riders. This was no longer an off-road event, this was motorcycles versus social harpies. Louis McKey provided a personal note, a focus for enthusiasm.

And Wolfe saw it first with pressure group politics—the street fighters aligned with The Duck made the AMA and its affiliated clubs the more responsible parties, groups with whom the BLM and various other agencies could reason.

The clubs in their turn learned a lot. The Sierra Club may have in fact done us all some good. Open desert racing has had its day, just as hunting grizzlies was vital, then harmful. The AMA and the racing clubs learned the new rules. They raised the money, attended the public hearings and the lawsuits.

When the Saturday after Thanksgiving rolled around for 1982, the BLM rejected the annual application for a race but with the notation that next year, if all forms were filed, all “t”s crossed and “i”s dotted, the race would be approved. And BLM issued maps for the trail ride; they knew by this time that the protest riders really did want to play fair.

Thus, the 1983 application was approved. There were many restrictions, for example a limit of 1200 riders, with no more than 400 starting at once. The approved route began at the traditional starting area east of Barstow, but because of exurban sprawl, the finish was moved about 10 miles west of the old finish. The course was laid out to use durable territory. By the BLM’s reckoning, 52 percent of the course was on existing trails, 28 percent in sandwashes, 20 percent on the old race course and less than one percent, call it one mile, of new ground.

The Sierra Club filed suit to stop the race. U.S. District Court Judge Wallace Tashima inspected part of the course from a 4WD truck, the rest from a helicopter. He ruled that the AMA and the sponsoring club had made proper application, that the BLM had considered all the facts, that the race would not damage the desert; all systems go. The Sierra Club appealed and the appeals court upheld the district court.

So it came to pass that at 8 a.m. of the Saturday after Thanksgiving, 1983, a smoke bomb sent the first wave toward Las Vegas.

The 1983 race had aspects of media event. All three national networks had helicopters in the air, all the newspapers from the area had reporters and photographers, there were even some pickets bearing signs with “Park It” and “Racers Go Home.” (One of the newspapers took photos of the picket signs lying discarded on the ground after the start, but for all we know the protesters cleaned up later.)

When the smoke bomb went off, the race became just another race. There were 1056 official starters competing in 26 classes. A collision early in the first wave delayed the other waves by nearly an hour. There were five injuries serious enough to be reported.

A little more than three and a half hours after the start, Dan Smith, a Team Husqvarna member and also winner of this year’s Baja 1000, crossed the line for first overall. There were 525 official finishers, official meaning riders who not only crossed the line, but had their tank cards signed off at all the check points.

When the finish line officially closed there were 48 riders unaccounted for, that is, they knew where they were but their crews didn’t. And there were bikes unaccounted for, broken machines and tired men leaning against the fence along Interstate 15, all normal Barstow to Vegas. Also normally, by the time the awards were handed out, all riders and crews were back together, all lost bikes were found.

And the BLM was reporting good news. The racers had obeyed the rules and followed the course. The newspapers quoted one Sierra Club spokesman as saying the racers obeyed the rules. Of course, he added, they will file a protest next year anyway.

(Incidentally the B to V poker run, sponsored by the Victor McLaglen Motor Corps, drew 700 entries, so that, too was a success.)

The award for the racer who came the longest distance was declared a tie: Somehow it didn’t seem right to measure the miles from Belgium and compare them to the miles from Australia. Both racers had a wonderful time.

.Winner of the Senior Open Expert class, and 24th overall, was Cycle World’s own Ron Griewe.

Eddie Lawson, yes, the same, the world class road racer and winner of the TV Superbikers contest, was 128th overall and 23rd Open Expert. He’d never raced the desert before, but the race committee figured he’d be a bit quicker than the average novice, which of course he was.

Meanwhile, back in the second row, riding his brand new Yamaha XT250 equipped with a special No. 1 plate, was Louis McKey. The bike was a bit too new and suffered some troubles, including a flat tire, so the Phantom Duck of the Desert didn’t officially finish.

But when they handed out the trophies all the racers, the officials and crews, everybody in the place, rose as one and gave McKey a standing ovation.

They, make that we, all us motorcycle nuts, couldn’t have done it without him. His eight year effort to revive the Barstow to Vegas race has made Louis McKey, the Phantom Duck of the Desert, something of a political activist. Because he doesn’t figure the fight is over yet, he’s starting a club.

The Phantom Duck Club isn’t a motorcycle club in the usual sense. Instead, it’s associated with the California Off Road Vehicle Association, itself composed of motorcycle, jeep and trucks groups working with rockhounds and other desert enthusiasts. They lobby, promote and well, take part in the democratic process.

Charter memberships go for $50, which brings a club (with your name) jacket, a Duck T-shirt, a club patch and the CORVA newsletter. Write to Louis McKey, 7896 Kempster Ave., Pontana, Calif. 92335. H

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

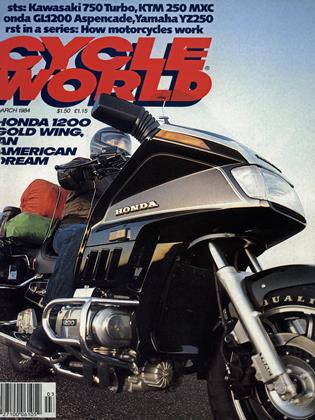

DepartmentsCycle World Up Front

March 1984 By Allan Girdler -

Cycle World Letters

Cycle World LettersCycle World Letters

March 1984 -

Technical

TechnicalCycle World Follow Up

March 1984 -

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Round Up

March 1984 -

Special Feature

Special FeatureHow Motorcycle W.O.R.K 1

March 1984 By Steve Anderson -

Technical

TechnicalPainting Plastic

March 1984