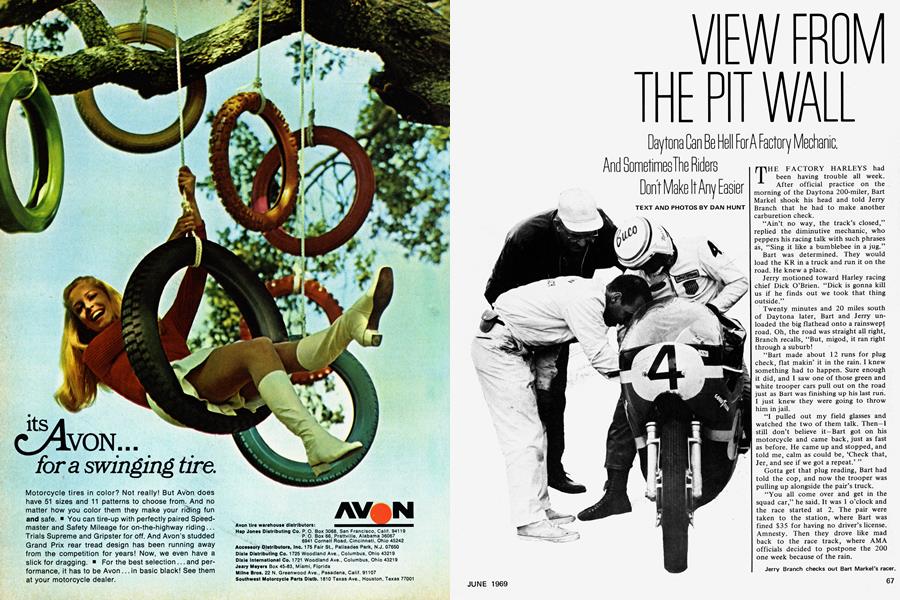

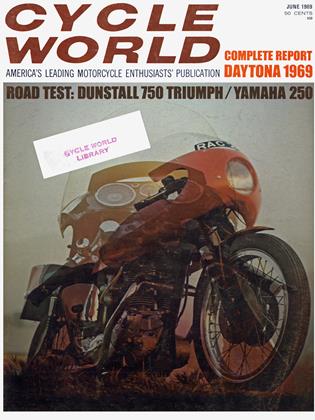

VIEW FROM THE PIT WALL

Daytona Can Be Hell For A Factory Mechanic, And Sometimes The Riders Don't Make It Any Easier

DAN HUNT

THE FACTORY HARLEYS had been having trouble all week. After official practice on the morning of the Daytona 200-miler, Bart Markel shook his head and told Jerry Branch that he had to make another carburetion check.

“Ain’t no way, the track’s closed,” replied the diminutive mechanic, who peppers his racing talk with such phrases as, “Sing it like a bumblebee in a jug.”

Bart was determined. They would load the KR in a truck and run it on the road. He knew a place.

Jerry motioned toward Harley racing chief Dick O’Brien. “Dick is gonna kill us if he finds out we took that thing outside.”

Twenty minutes and 20 miles south of Daytona later, Bart and Jerry unloaded the big flathead onto a rainswept road. Oh, the road was straight all right, Branch recalls, “But, migod, it ran right through a suburb!

“Bart made about 12 runs for plug check, flat makin’ it in the rain. I knew something had to happen. Sure enough it did, and I saw one of those green and white trooper cars pull out on the road just as Bart was finishing up his last run. I just knew they were going to throw him in jail.

“I pulled out my field glasses and watched the two of them talk. Then—I still don’t believe it—Bart got on his motorcycle and came back, just as fast as before. He came up and stopped, and told me, calm as could be, ‘Check that, Jer, and see if we got a repeat.’ ”

Gotta get that plug reading, Bart had told the cop, and now the trooper was pulling up alongside the pair’s truck.

“You all come over and get in the squad car,” he said. It was 1 o’clock and the race started at 2. The pair were taken to the station, where Bart was fined $35 for having no driver’s license. Amnesty. Then they drove like mad back to the race track, where AMA officials decided to postpone the 200 one week because of the rain.

Jerry Branch is not likely to forget Daytona 1969 very soon. It was a two-week trauma. About the only good thing that happened to him was that Bart gave him a new watch for Auld Lang Syne. Rayborn won the race, which offers him satisfaction. And Bart finished—for the first time.

The average workday for him and the other Harley-Davidson mechanics was 18 hours. Jerry and Clyde Denzell, Cal Rayborn’s tuner, worked together on one stretch that went 53 hours straight. The troubles with the H-D team engines were so manifold that they all had to be torn down and reassembled at least two times and some of them even more. And this included machines for messieurs Rayborn, Reiman, Markel, Lawwill, Haaby, Fulton, Nix and Brelsford.

What’s it like to mech at Daytona with a racing team like that? In normal years it’s hectic.

“A lot of people think it’s party time,” says Branch. “It’s not so. You can see old friends you haven’t seen for years and not have time to say hello. This year it was even worse. H-D was really perturbed. The riders were getting to us. We were buffaloed.”

“Buffaloed” is Branchese for “too many variables.” The tuners had no positive answer to their problems even after they were able to get Rayborn’s machine running fast enough to win.

The variables began making themselves felt as soon as preparation for qualifying got under way at Daytona. Although dynamometer tests indicated that the racing engines should develop 3.8 bhp more than last year’s (about 55 bhp), they were false. No complete engine had, in fact, been run on the dyno—only a one-cylinder mock-up.

New pistons with 0.600-in. radiused domes, hastily machined, were not to exact specifications. Unused to megaphonitis, as Harleys have run straight pipes until this year, riders at first reported that the machines acted as if they were running too rich, when, in fact, they were running too lean. Then it was discovered that it was virtually impossible to get “repeat” readings—i.e., identical plug color on two back-to-back test runs with settings unchanged. Part of this was attributed to varying diaphragm spring tension on the new racing Tillotson carburetors, none of which was tested on the dyno due to lack of time. Valve/head/piston clearances varied from engine to engine. The spot disc rear brake on all machines gave the mechanics constant trouble, right through to the end of the 200-miler. Markel’s tore completely off its mountings during the race and locked solid in the caliper. Many of the team also had trouble with their tachometers, which gave inaccurate readings or broke completely.

This variability did crazy things. It caused riders and mechanics to lean out engines to the point that the pistons melted. Even in the second week, after the 200 was postponed, the mechanics who remained behind got onto a tangent about putting reverse copes on the megaphones, because they seemed to clean up running at low rpm. But the crew would change the setup on one machine, run it down a three-mile straight with another machine it previously matched, and there would be no difference. At other times, unaccountably, one machine would “flat just run away” from all the other bikes. Late in the second week, after it was thought that most of the machines were at least up to last year’s standards, Roger Reiman and his mechanic, Babe Demay, fitted cylinders and head from his flattrack racer to his road racing engine, and it outperformed all the other bikes—in supposedly more powerful road racing fettle—in acceleration and top speed.

The mechanics also had to cope with the idiosyncrasies of the riders. This isn’t something that happened this year only, says Branch, it happens all the time. Several of the riders are incorrigible fiddlers, and unfortunately the main jets of the Tillotson carb are accessible enough to be adjusted by a rider while he is running 140-plus mph on the banking. Both Bart Markel and Mert Lawwill are on Branch’s fiddling list. “It’s terrible,” he says. “They can’t even remember which way they turned it. Bart’s a good mechanic, but that doesn’t mean he’s a good tuner.”

Some of the other riders can’t even report symptoms properly, and, instead, they come in from a practice run and say something like, “It’s too rich.” So the mechanic leans the carburetors out, which, it turns out later, was exactly the wrong thing to do, and the engine burns up. Freddy Nix, who was the top mile oval rider in the nation last year, gives a lousy report of what’s happening, and can get overly perturbed, as well as being a fiddler.

The most informative riders seem to be Cal Rayborn and Roger Reiman. Cal is not a mechanic/rider (“He doesn’t really know what the hell you’re doing”). But he reports accurately what is happening to the machine. He is particularly useful for sorting out handling, because he is faster through the turns than the other riders by about 5 mph, and he runs into problems at those speeds that the others wouldn’t even suspect. Branch characterizes Reiman, who won the 200 twice in a row, as an excellent mechanic/rider, “all business” when he comes down to race. Reiman is thoroughly familiar with the problems of delivering a good report to his mechanics, because he is a test rider for the Goodyear tire development staff, which also gives him an edge racing in the rain. Branch also feels Dan Haaby (“I think

I’d really enjoy working with Dan”) and Walt Fulton Jr. are extremely intelligent riders and data-gatherers.

When the riders are acting up, the mechanics have ways of getting even, often to the benefit of the rider, and his machine. Jerry gives a classic account of an incident that happened between Mert Lawwill and his mechanic, Jim Belland:

“Mert comes in and keeps tellin’ Jim, ‘It’s too rich.’

“And you say, okay, fine. You reach up under there and you don’t even touch ’em and you move your hands.

“ ‘Okay,’ you say, ‘that’s an eighth of a turn.’ So Mert goes out and comes back in.

“How’s that?

“Mert says, ‘Lot better. Little bit more!’

“ ‘Okay! How’s that?’ you say. And he goes out again and comes back.

“ ‘Right on the old button!’ ”

“You just know it’s psychological,” says Branch, breaking into gales of laughter. “We must have done this half a dozen times this year. Mert isn’t the only guy. We did it to everybody else, too. Hey, really, they don’t know the damn difference.”

But Mert is definitely the “psycho” rider of the bunch. He is capable of out-racing any rider in America anywhere when he’s on the bubble, Branch says, “But if you walk up to him before a race and say ‘Mert, your wheel looks out of shape,’ he might as well give up, right there.”

Fred Nix also gets “psyched,” Jerry says, but in a slightly different way. He seems to rely too much on one mechanic, and loses effectiveness when thrown in with somebody else.

Several of Branch’s observations do much to dispel the typical “glory boy” image attributed to AMA professional riders. Bart Markel, for example, may have been star-seeking in the past, desiring to follow in the footsteps of his idol, Carroll Resweber, but now “he wants the dollars and cents.”

“Bart once told me that carrying the No. 1 plate meant an additional $500 a week in appearance money. The other national numbers may get $50 for travel expenses. So he really wants to get that No. 1 back. It isn’t fun anymore. He doesn’t care how much money a single race pays. He wants those points.

“Mark Brelsford is fresh, and he’s still racing for the pleasure of it. Caution is catching up with Bart, and he’s tense and fidgety. He tries things he shouldn’t.

“Fulton is perhaps second only to Rayborn on a road race course. He’s got that young drive. And he can put it over on Reiman, although Reiman can outfox him on occasion. Roger is probably the cagiest of them all.

“Dan Haaby is a great racer, although I think he’s not as comfortable at the high speeds you get on a track like Daytona. He’s good to work with, and he’s not bitchy or gripy. He’s like Roger. If Roger’s motor goes out, he’s not all excited. Sure he’s disappointed, mentally and financially, but that’s part of the game.”

Often, then, what looks to the fans like a thrust for glory may only be the outward evidence of a man trying to extend his limitations, or simply make a living the best way he knows. The real play is directed inwards, but the people in the stands thinks it is all for them. If they only knew.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Round Up

June 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Scene

June 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

The Service Department

June 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1969 -

Legislation Forum

Legislation ForumSpecial Report: the Moving Forces Behind Motorcycle Legislation

June 1969 By J. Bradley Flippin -

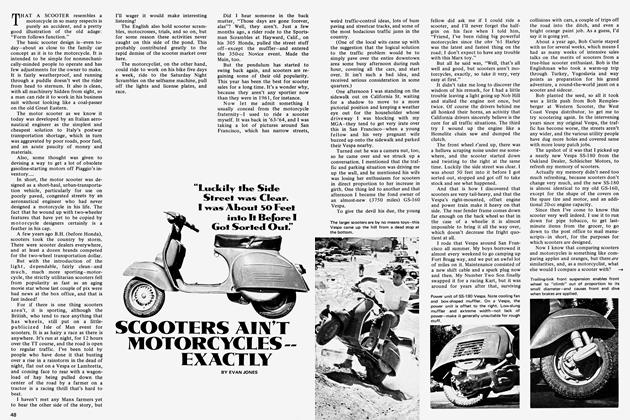

Offshoot Dept.

Offshoot Dept.Scooters Ain't Motorcycles-- Exactly

June 1969 By Evan Jones