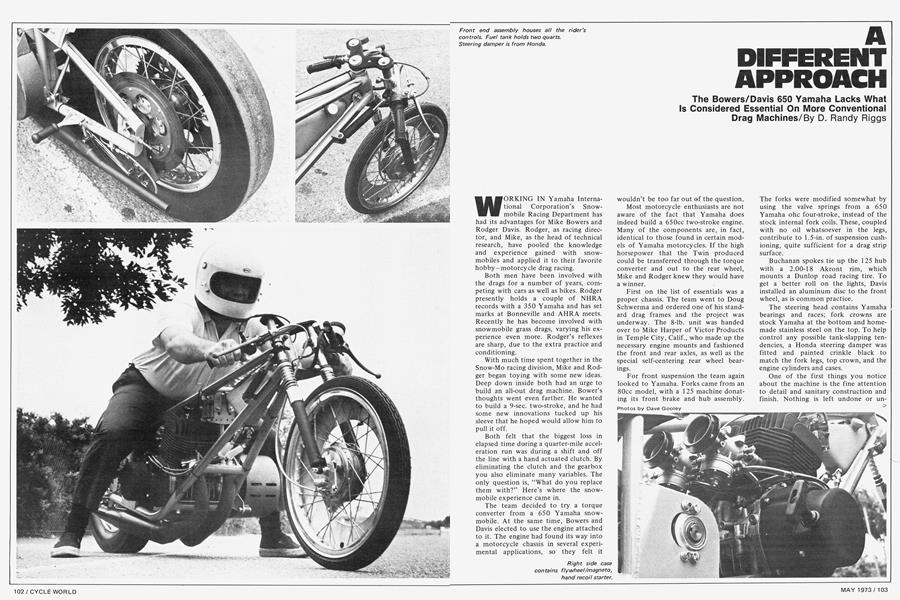

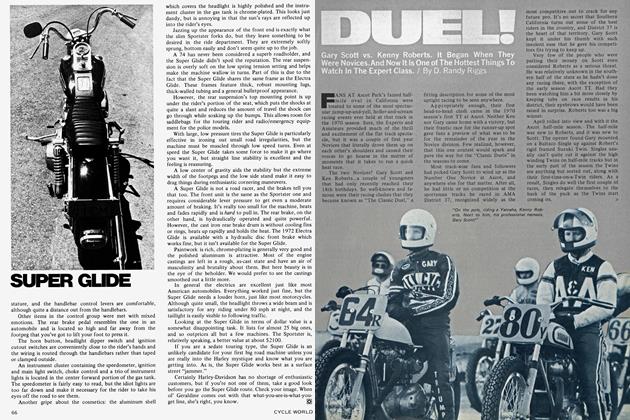

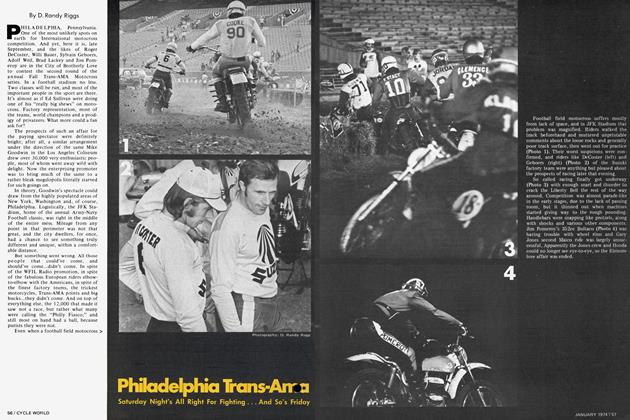

A DIFFERENT APPROACH

The Bowers/Davis 650 Yamaha Lacks What Is Considered Essential On More Conventional Drag Machines

D. Randy Riggs

WORKING IN Yamaha International Corporation's Snow-mobile Racing Department has had its advantages for Mike Bowers and Rodger Davis. Rodger, as racing director, and Mike, as the head of technical research, have pooled the knowledge and experience gained with snow-mobiles and applied it to their favorite hobby—motorcycle drag racing.

Both men have been involved with the drags for a number of years, competing with cars as well as bikes. Rodger presently holds a couple of NHRA records with a 350 Yamaha and has set marks at Bonneville and AHRA meets. Recently he has become involved with snowmobile grass drags, varying his experience even more. Rodger’s reflexes are sharp, due to the extra practice and conditioning.

With much time spent together in the Snow-Mo racing division, Mike and Rodger began toying with some new ideas. Deep down inside both had an urge to build an all-out drag machine. Bower’s thoughts went even farther. He wanted to build a 9-sec. two-stroke, and he had some new innovations tucked up his sleeve that he hoped would allow him to pull it off.

Both felt that the biggest loss in elapsed time during a quarter-mile acceleration run was during a shift and off the line with a hand actuated clutch. By eliminating the clutch and the gearbox you also eliminate many variables. The only question is, “What do you replace them with?” Here’s where the snowmobile experience came in.

The team decided to try a torque converter from a 650 Yamaha snowmobile. At the same time, Bowers and Davis elected to use the engine attached to it. The engine had found its way into a motorcycle chassis in several experimental applications, so they felt it wouldn’t be too far out of the question.

Most motorcycle enthusiasts are not aware of the fact that Yamaha does indeed build a 650cc two-stroke engine. Many of the components are, in fact, identical to those found in certain models of Yamaha motorcycles. If the high horsepower that the Twin produced could be transferred through the torque converter and out to the rear wheel, Mike and Rodger knew they would have a winner.

First on the list of essentials was a proper chassis. The team went to Doug Schwerma and ordered one of his standard drag frames and the project was underway. The 8-lb. unit was handed over to Mike Harper of Victor Products in Temple City, Calif., who made up the necessary engine mounts and fashioned the front and rear axles, as well as the special self-centering rear wheel bearings.

For front suspension the team again looked to Yamaha. Forks came from an 80cc model, with a 125 machine donating its front brake and hub assembly. The forks were modified somewhat by using the valve springs from a 650 Yamaha ohc four-stroke, instead of the stock internal fork coils. These, coupled with no oil whatsoever in the legs, contribute to 1.5-in. of suspension cushioning, quite sufficient for a drag strip surface.

Buchanan spokes tie up the 125 hub with a 2.00-18 Akront rim, which mounts a Dunlop road racing tire. To get a better roll on the lights, Davis installed an aluminum disc to the front wheel, as is common practice.

The steering head contains Yamaha bearings and races; fork crowns are stock Yamaha at the bottom and homemade stainless steel on the top. To help control any possible tank-slapping tendencies, a Honda steering damper was fitted and painted crinkle black to match the fork legs, top crown, and the engine cylinders and cases.

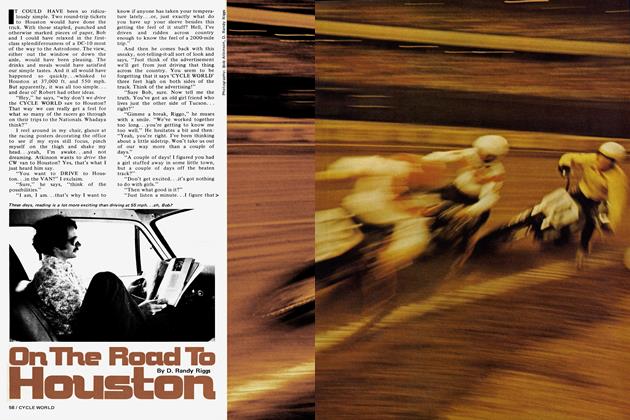

One of the first things you notice about the machine is the fine attention to detail and sanitary construction and finish. Nothing is left undone or uncared for. Every rivet, bolt or nut is either plated or buffed. Each wire or cable is routed precisely in position. Safety is built-in. It’s as much a part of the machine as the engine, and was one of the team’s main objectives.

The 2-qt. fuel tank was built by steel shoe man Ken Maeley. It’s formed from anodized aluminum and nestles just behind the steering head between the frame rails. Normal, everyday pump gasoline is used at the present, since the bike competes in the NHRA G/Gas class.

Rodger steers with Webco clip-on bars that mount the control levers for both the front and rear brake assemblies. The right lever operates the cable actuated front brake, just like on most motorcycles. The left one is a bit out of the ordinary, however. Why? Have you ever seen a left hand hydraulic brake unit? Probably not. This is one of the few ever produced, made originally for a Yamaha snowmobile.

The master cylinder operates the rear brake, which is a Kelsey Hayes disc and caliper combination. Davis was quite particular about choosing his brakes and that’s mainly why he used stoppers at both wheels. If he were to lose his rear brake for any reason and had no front unit to back it up, he’d be in big trouble at 135 mph. The torque converter would do nothing to slow the machine, unlike a transmission with which you could at least shift down.

For traction Bowers and Davis went to an M&H drag slick, in which they normally carry about 12 to 13 lb. of air for most strips. The 4.00-18 tire fits on an Akront rim. Sheet metal screws run through the rim and into the sidewall of the tire to secure the tire to the rim without danger of it slipping and tearing out the valve stem.

The 68-in. wheelbase machine gets its go from a very unusual power and drive

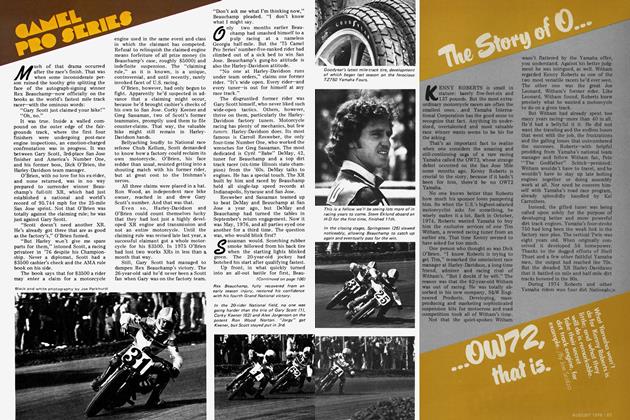

combination. To date it’s been sufficient enough to carry Rodger and the bike to a very fast 10.009 e.t. with a speed of 134.86 mph. If that sounds slow compared to the nine flats turned in by some of the Harleys, remember this thing runs in G/Gas. The record for the class is in the neighborhood of 10.80, so you can see the Bowers/Davis bike is trick.

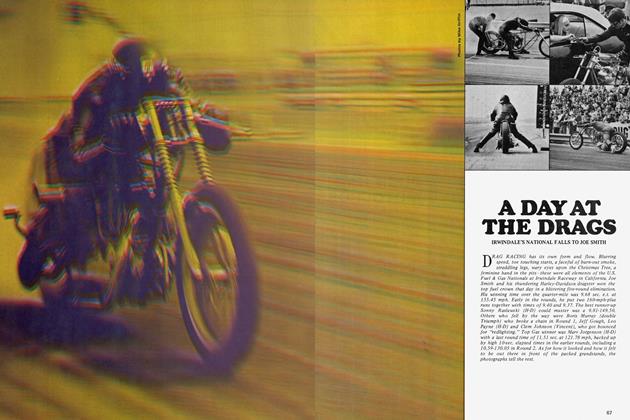

The Yammy mill actually displaces 643cc and produces right around 100 horsepower. You’d probably be a nonbeliever until you watched this thing go. It’s enough to temporarily displace brain fluid. Crankcase halves separate horizontally and house a sturdy looking crank assembly. The right side of the crankshaft mounts the Yamaha magneto system and flywheel. The left side is more interesting. This is where we find the unique drive system—the torque converter.

The primary clutch unit is attached directly to the crank. This-unit has a spool that the drive belt runs around. On the end of the spool is the actual clutch assembly, a group of contracting discs that change when engine rpm is increased. The drive belt is toothed to mesh with corresponding grooves in the spool assemblies.

The belt runs from the primary clutch assembly to the secondary clutch assembly, which works just the opposite. Its discs expand, rather than contract, and the end result is a change in the overall gear ratio from 0:1 to 1:1 at top speed. By making certain adjustments, the ratios can be made to change at different rpms to suit different engines. Presently, the engine develops its power at 8000 rpm, so the clutches are set up to change when the unit reaches that peak.

To transfer the power from the secondary unit to the rear drive chain, a jackshaft was built. It rests in mounts built into the frame and carries a primary sprocket on its end. That in turn connects to the chain which continues

to the rear sprocket and the linkup is completed. As complicated as the unit may sound, it is actually very simple, and very efficient.

The rider has no worries about a missed shift or feathering the clutch off the line. Rodger simply watches the lights, twists the throttle when the light goes green, and steers—that’s it!

The team had Tom Rightmeyer build a magnesium cover for the entire assembly, and even though it looks large, it only weighs 1.5 lb. Items such as this contribute to an overall weight of just 186 lb., probably the lightest 650 drag machine ever.

Another unusual item is the method of supplying fuel to the cylinders. Two 50mm Keihin diaphragm carburetors are actually a carb-injection system. They work off of crankcase impulses and deliver fuel at an alarming rate! They have no floats of any kind and are not affected by varying temperatures. The starting drill is simple: turn on the petcocks, hold a hand over one of the carb intakes, and pull the hand recoil starter. Just like a lawnmower!

The machine is allowed to idle and warm up. If any revving is needed, the rear wheel must first be raised off the ground; otherwise, the bike will take off. It’s just like riding a mini-bike with .a centrifugal clutch, only faster.

Finishing off the pacesetting machine is a Schwerma seat and an eyecatching racing orange color accented with gold touches. Pipes by Wheelsmith Engineering of Santa Ana not only help with the performance but fit in with the quality of the remainder of the bike.

The team of Bowers and Davis have come up with a truly innovative machine. The word is that they’re working on another. We can only imagine what that will be like.... [<5