Yamaha's V-Twin Dirt Bike

A First-Class Team,The Right Design, And A Price That's A Sight For Privateer Eyes.

Allan Girdler

All the components of Yamaha's flat track racer are a combination made, if not in Heaven then surely in the winner's circle.

Yamaha has supported racing with piles of money and parts and privateer support since the days of the roadracing TD-1. The Virago 750 V-Twin is new and strong, the perfect size and shape without the handicap of changing displacement (Honda) or adapting from older designs (Harley).

The team has most impressive credentials. It says in the fine print that the AMA/Winston Pro effort is not a factory team. Instead, the dirt track bikes come from Roberts/Lawwill Racing, a subcontractor. Principals are Kenny Roberts and Mert Lawwill, with help from Dick Mann and C.R. Axtell. This independence works in both ways. Yamaha the factory cannot lose because Roberts/Lawwill is the entrant, and Roberts/Lawwill in turn has the freedom to do things (as we'll see) forbidden to the factory-direct Honda and Harley teams.

For Lawwill and partners the Yamaha project must have been a dream come true. The tuners have hundreds of dirt track victories among them. They know what Harleys and the previous Yamaha vertical Twins do and don't do. AMA rules declare the engine to be the motorcycle; frame, suspension, brakes, etc., are builder's choice. Production means no fewer, than 25 examples must have been produced and are for sale to the privileged public, i.e. racing teams and dealers get theirs before the man off the street does.

Yamaha's tracker, though, is an honestto-goodness production engine. Yes. Seems that the Virago in America and the XV750 in Europe are shaft drive V-Twins, while at home in Japan the 750 comes with shaft or chain drive, a small bore version of the American 920 and European 980. The differences amount to no more than slightly different castings for the gearbox, to use a countershaft with sprocket for the chain instead of the bevel gear and housing for the shaft. Nothing to it. When you consider that the Honda track engine is a bored, stroked, turned sideways and re-gear boxed version of the CX500 and the current Harley XR750 is an alloy version of the iron racing engine made by de-stroking the early Sportster that was really an overhead valve conversion of the flathead 45 circa 1936, why, maybe Yamaha should suggest that the production regulations be tightened up some.

For American racing, all the Yamaha 750 needs is a new left side cover of aluminum plate, narrowing the engine while removing the stock ignition and alternator. The builders say that in part because the basic engine was designed to come in 980, 920 and 750cc versions, the crankshaft and lower end are strong enough to go racing as they come from the production line. The first engines were delivered to Lawwill, who worked with Axtell and Mann to develop pistons and camshafts and rework the ports, etc., to get enough horsepower in the right place.

As first seen in public the 750 uses two 38mm Dell ‘Orto carbs. The intakes are within the vee so the rear carb faces front and the front carb faces the rear. One of the few shortcomings of the production engine converted for racing is the rear exhaust pipe, which exits the back of the head and must then be snaked down behind the gearbox and in front of the swing arm. The pipe blocks air flow and radiates its own heat, to the extent that the rear cylinder runs hotter than the front, and the pipe is shorter than Axtell would like. There's some loss in power from both the above; further, the length and the heat require the back barrel to use a different cam than the front has.

Ignition is driven off the front camshaft, with a set of points and a coil for each cylinder. Actual power developed for the first races is something of a secret. The team will cheerfully banter figures like 80 bhp, which is what the Harleys will develop if not leaned on too hard, and Lawwill says his engine will run for 100 mi. without fatigue. The Yamaha seems competitive after nine weeks' development. There is more power to come, as needed, and experiments are currently underway to see what happens with shorter connecting rods and such. More beans may mean more will be done to the stock clutch and gears, but for now, the engine is right on schedule.

As a technical oddity, Yamaha's Twin runs backwards, that is, counter to the rotation of the wheels. This allows the drivetrain to rotate in the proper direction without extra jackshafts or such.

But. One of the oldtime racing theories was that engine rotation affected chassis balance; for every action, the physics books say, there's an equal and opposite reaction. Thus, if the engine runs clockwise, the front wheel will lift while the driving wheel is pushed down. There have even been tuners who built engines that counter-rotated, on the belief that they could get something for it.

Lawwill says it isn't so, or at least with modern suspension and balance, what effect crankshaft direction may or may not have isn't enough to be worth worrying about. They're glad because that spares the team the trouble of asking the factory

for engines spinning the other way, but in any case, it's just one more intriguing myth that fails the test.

Frame and suspension are still being developed. The construction was done by Mann, who has been building winning dirt track bikes since Yamaha invented the piano. Mile and half-mile racing is more sophisticated than it looks. American racers have been turning left and getting on the power for 70 years. The rules have changed, ditto tires and suspension and engines but the principles have not. The competition is professional and intense. Getting exactly the right balance, fore and aft, side to side and track surface to center of gravity, is a matter of fractions here and there making the difference between the Number One plate and not qualifying for the main event.

Mann has come up with a beautifuf frame literally not built around the engine. Harley engines are made for full cradle frames, so racing Harleys have them. The Honda miler's CX500-based engine was designed to be a stressed member but the racing version has a full cradle.

The Yamaha 750 is semi-stressed, designed to hang from a giant pressed-steel backbone in front and center, and have the gearbox serve also as the swing arm pivot.

Mann laid out what amounts to the top* half of a birdcage frame. A center backbone tube runs straight back from the middle of the steering head. Below it is the world's shortest downtube, to the front engine mount on the forward cylinder head. The side tubes—to coin a term—run from the top of the steering head down and out,4 around the cylinders to the bottom of the vee, where's there's a new engine mount, then back to the gussets and brackets tying together the rear mounts, swing arm pivot and tubes from the rear triangle that carries the seat and upper shock mounts. There's also a pair of wide rear downtubes, from the main backbone to the rear mount. Nice work, all of it, and a good blend of dirt track and the latest in road race design.

Front suspension at the bike's first two appearances was Simons leading axle forks, as in motocross but with less travel. kRear shocks were by Works Performance. In both cases the damping and spring rates were done to Lawwill's and Mann's suggestions. Suspension is mostly conventional and not final. Leading axle forks have never done well on miles and half miles. Straight leg Marzocchis and Cerianis are more popular and Lawwill is trying all kinds. The same goes for steering head rake, offset and trail. At San Jose the team bikes had offset triple clamps with the stanchion tube inclination steeper than the steering head. Team members said the forks used there were only one of three ^configurations being tested.

Swing arms are square-tube steel, and the shocks are mounted just in front of the rear axle and tilted forward to the degree also used by Harley and Honda. This gives a hint of rising rate but not much and if any flat track builder has considered single shocks, as in motocross and road racing, either it hasn't worked in private or nobody's bothered to build one. Mile and half-mile tracks don't lend themselves to exotic devices.

Nor are there many firm figures. Wheelbase can be changed to suit track conditions, but will fall between 53 and 57 in., again normal for the class. Claimed dry weight for the Yamaha 750 is 300 lb.,

compared with 310 lb. for a dry Harley XR750 and 290 lb. for the Honda NS750. All three, it must be said here, are weights given by the teams for themselves and each other, and have not been subjected to outside audit.

At their debut the two Roberts/Lawwill machines were works of art, detailed and polished and painted—blue and silver, not yellow and black—to perfection. The Honda NS750s made the Harleys look trim and tidy. The Yamahas made the Harleys look like production racers halfway through a tough season.

At checkered flag time, though, the Harleys were 'way out in front.

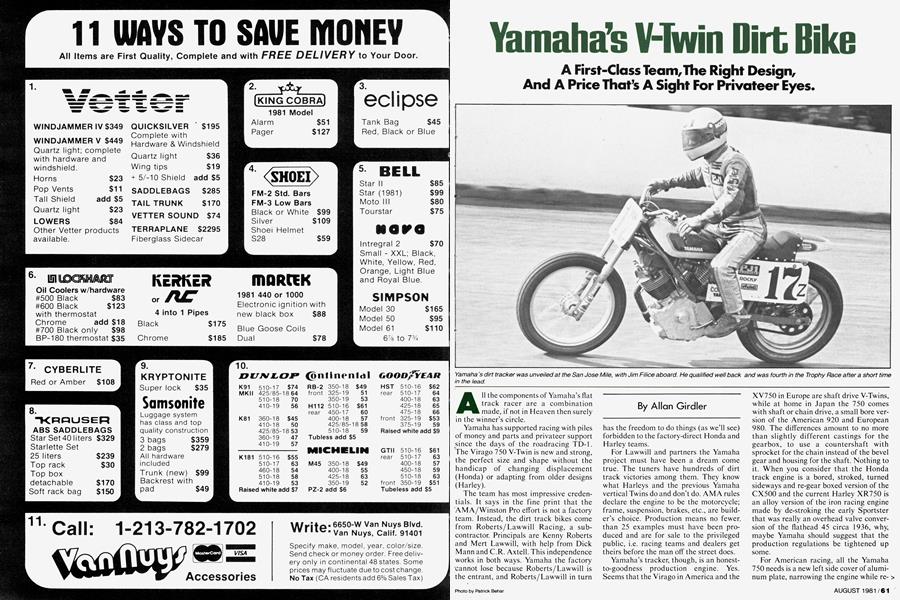

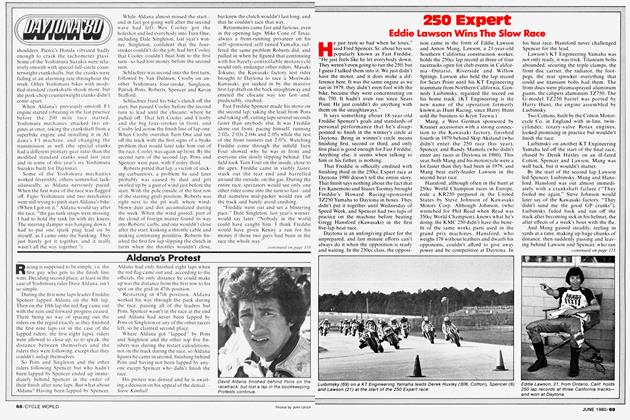

Races aren't won on the dynamometer nor in the lab. Roberts/Lawwill had two bikes at the San Jose mile, one for Mike Kidd and one for Jim Filice.

Team Roberts/Lawwill also had teething troubles. The Yamahas didn't handle. They didn't turn and when they did they got away from their riders. It was obviously suspension. What wasn't obvious was which part of the suspension and why able to keep up with the Harleys, Lawwill rolled out his Harley and Kidd rode it to the fourth fastest time in qualifying, first in his heat and sixth in the national. Filice on the Yamaha was 26th fastest in qualifying, missed the cut in his heat and was fourth in the trophy race. Yamaha made an appearance, and Team Roberts/Lawwill made sure their top rider got useful points.

At Ascot the following week neither Yamaha 750 would handle. After practice both were withdrawn. Filice had the evening off and Kidd rode the Harley to

fourth in the national. As of late May Kidd was fourth in the national standings. Not bad for a factory rider with options, seeing as how Freddie Spencer, a factory rider with iron-clad contract, has yet to earn a national point.

What else? More work. Lawwill says there will be different pieces in the frame, different bits on the suspension and more tuning of the engine. After nine weeks the Yamaha was close to the Harley after nine years. Team Roberts/Lawwill expects to win some by the end of the year.

Meanwhile, Yamaha's dirt track program genuinely isn't a factory effort. The factory, meaning Yamaha itself, isn't much interested in flat track.

The motivation came from Yamaha dealers, who wanted very much to see their brand back on the miles. (And Roberts on the bikes, but that's another story.) So the Yamaha engine is truly production, and the price can be right. The rules say 25, but Yamaha shipped in 75 engines and the price, for dealers, supply your own frame and other parts, is $1700. Harley engines go for $5000 and need work before they'll run with the others. Honda hasn't set a price yet but rumor has it nearer $10,000, on grounds Honda wants to run the program from headquarters. Privateers are welcome at Yamaha, in other words, and that's bound to help all the racers.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

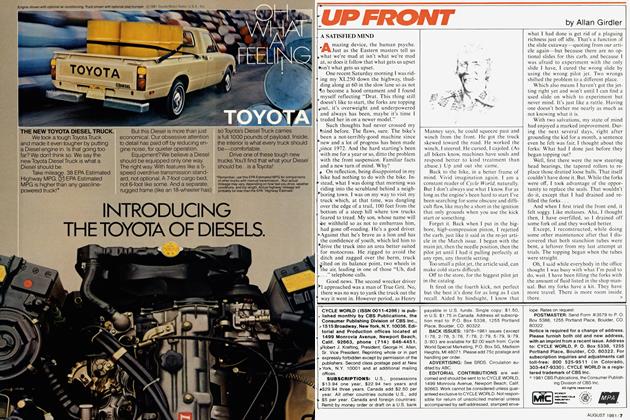

Up Front

Up FrontA Satisfied Mind

August 1981 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1981 -

Book Review

Book ReviewBrooklands Behind the Scenes

August 1981 By Henry N. Manney III -

Departments

DepartmentsRoundup

August 1981 -

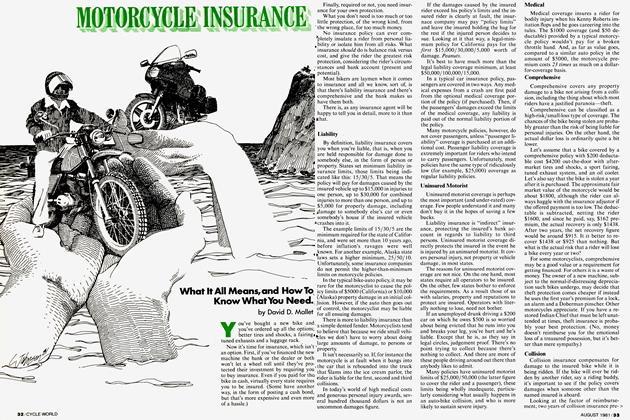

Motorcycle Insurance

Motorcycle InsuranceWhat It All Means, And How To Know What You Need.

August 1981 By David D. Mallet -

Motorcycle Insurance

Motorcycle InsuranceNot All Motorcycle Insurance Companies Are Alike. Some Take Your Money And Go Out of Business.

August 1981 By John Ulrich