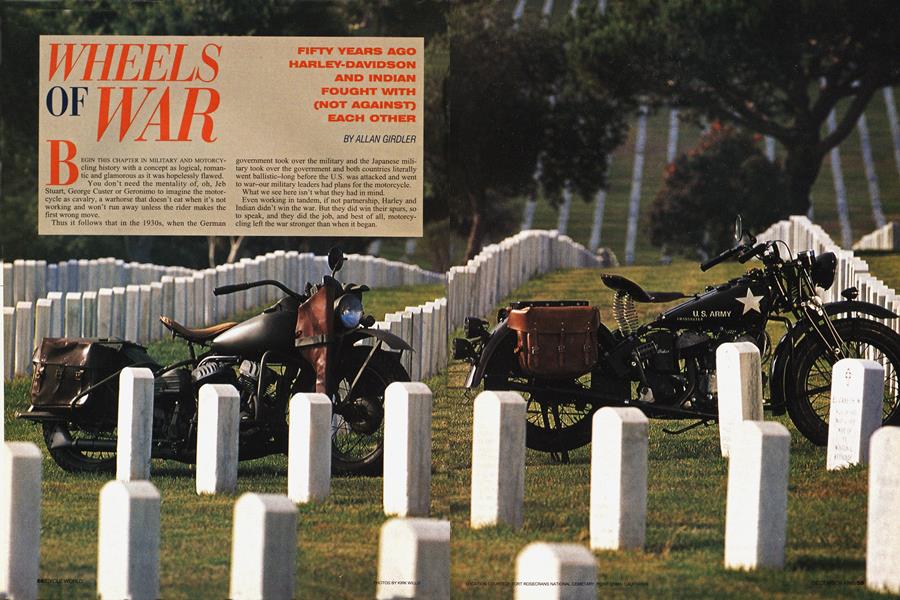

WHEELS OF WAR

FIFTY YEARS AGO HARLEY-DAVIDSON AND INDIAN FOUGHT WITH (NOT AGAINST) EACH OTHER

ALLAN GIRDLER

BEGIN THIS CHAPTER IN MILITARY AND MOTORCYcling history with a concept as logical, romantic and glamorous as it was hopelessly flawed.

You don’t need the mentality of, oh, Jeb Stuart, George Custer or Geronimo to imagine the motorcycle as cavalry, a warhorse that doesn’t eat when it’s not working and won’t run away unless the rider makes the first wrong move.

Thus it follows that in the 1930s, when the German government took over the military and the Japanese military took over the government and both countries literally went ballistic-long before the U.S. was attacked and went to war-our military leaders had plans for the motorcycle. What we see here isn’t what they had in mind.

Even working in tandem, if not partnership, Harley and Indian didn't win the war. But they did win their spurs, so to speak, and they did the job, and best of all, motorcycling left the war stronger than when it began.

Concept first: Motorcycles were still in their infancy when they joined the Army. In 1916, Black Jack Pershing used Harleys in his energetic (if ultimately futile) pursuit of Pancho Villa along the U.S.-Mexican border, while by happy coincidence Villa rode and enjoyed an Indian. Most of the armies on both sides of WWI used motorcycles for scouting and running errands, and if they broke down and got stuck-which they did-so did the cars and trucks of the day.

Between world wars, our Army, and one assumes most of the other armies as well, rode and tested motorcycles to their limits and beyond. The machines improved. Germany did excellent work with sidecars that had power to both rear wheels, which was helpful when the Afrika Korps ran rings around the British in early desert warfare.

Backing up a few years, by the late `30s, world politics were at the point where if you had sense enough to know that power grows from gun barrels, you knew war was going to happen. Armies began all sorts of motorcycle projects, some useful, some justified and some not.

There were trials of three-wheelers, motorcycles rigged to be mini-trucks. These were hopeless and were quickly abandoned, while the military began exploring other ways to do the job (hint).

On a more practical note, the buyers-the guys in the branch that ordered equipment-had some ideas. Drive chains had long been a weak link, excuse the play on words, and slogging was more important than speed, so Harley and Indian were asked to submit prototypes of shaft-drive solo motorcycles.

The result was the finest pair of machines the two firms didn't make much of.

The Indian, coded 841, began as an engine the firm was already working on when the request arrived. It was a 90degree V-Twin, valves in the cylinders alongside the piston, set sideways in the frame, Moto Guzzi-like. It had shaft drive, as requested, and came with hand clutch and foot shift. Not only that, the rear hub was sprung and the girder fork had hydraulic damping, another innovation. It displaced 45 cubic inches-750cc we’d say now-making it a middleweight of that time.

The Harley entry, coded XA, was also a 750, but less radical. It was a frank and open copy of the BMW. an opposedTwin set across the frame, and also with hand clutch, foot shift and sprung rear hub. The front suspension originally was springer-style, as used on Harleys from the beginning, but late in the production run the XA got H-D's first telescopic front end.

The 841 and the XA were good bikes. They were submitted for testing and they performed well and the unofficial word was that as soon as the papers were all filled out and the procedures followed, the Army would order 25,000 examples of the winning design.

Then the ax fell.

Better make that the one-two punch.

First punch was that motorcycles weren’t as good at replacing the horse as had been expected. There was practice combat, with machine guns and scabbards and even some armor for sidecars, but in the field, riding and shooting was tougher than walking while chewing gum. War wasn't like a Steve McQueen movie. Bikes didn’t leap fences or ford rivers. As a punchline to that, the military insisted at first on lefthand throttles, to some degree because that would free the rider’s trigger finger from engine-room duty. But riding TT and sniping at the other side simply wasn’t practical.

The second punch was a project begun about the time the Army experimented with three-wheelers: It also invited the car people to fool around with something known then as a scout car; something light and sturdy and nimble...you guessed it ... the Jeep.

Four wheels, all driven, no special skills required for operation, the Jeep would ford rivers and climb hills and carry other soldiers or a family of refugees or a machine gun, whatever needed to be lugged there from here.

By July, 1943, Indian and Harley each had built 1000 841s and XAs, but instead of the big order, they got canceled. No more experiments, no more improvements, sorry about all the money and time and, oh yeah, here’s a couple of medals for the workforce.

So, what did they ride in the war? This is the good part. When the war was approaching, the USA was still a raw and rangy country with lots of long and lonely highways, unpaved as often as not. There was space between towns and no speed limits on what was still the open road. The American motorcycle, by then being Harley and Indian, was as raw and rangy as the country. The design was simple and sturdy, if you took time to take care of it, and the big engines were lightly stressed. filters, which didn't do much more than turn back the larger stones. There was an intermediate improvement from the factories, but the wear factor wasn’t eliminated until the engines were fitted with remote oil-bath filters, which were serviced with each engine-oil change.

Therefore, when the Army simply wanted motorcycles, vehicles to run errands and scout and report and explore-motorcycles to make tracks, not war-Harley and Indian were ready.

At the time, 1940 and 1941, H-D’s mainstay was the W series, 45-cubic-inch sidevalve VTwins with three-speed gearboxes controlled by hand shift and foot clutch. Front suspension was springer fork; rear suspension, in effect, was a rigidly mounted rear wheel and suspended saddle.

Rival Indian’s middleweights were Scouts, which came as plain and sport models, and with 30.50or 45-inch V-Twins. They also used hand shift and foot clutch, except the gear lever was on the right with throttle on the left, while Harleys had them the other way around. The Indians, called 741s, had girder forks and the same rigid rears with sprung saddles.

When the Army asked for samples and bids and specifications, Indian management somehow had the idea that they were supposed to be 30.50s, or 500cc. Harley was asked to offer a 500, but founding engineer William Harley said no, the engine wouldn't do the job.

He was right, and the Harley, designated WLA-W for the series, L for midrange state of tune and A for the Army-was clearly the better machine. Military preparation initially consisted of extending forks by 2-and-a-fraction inches, which added 2 inches to ground clearance beneath the engine, and then bolting on a skidplate because even 4 inches between crankcase and rocky ground wasn’t enough.

The Indian Scout, designated 741 in the 500cc form seen here, was given extended fork legs in front and longer frame tubes in back, which added up to 5 inches of static clearance. The engine was given milder cam timing and a lower compression ratio for less stress and cooler running, and the Scout engine was fitted with the stronger gearbox from Indian's Big Twin, the Chief.

The Army’s initial tests revealed some problems. Most serious, both the Harley and the Indian found the going tougher than their factories had expected. By the evidence, the unpaved highways of the day weren't nearly as demanding as the Army’s proving ground. The bikes bogged down in mud, ran hot in loose dirt, ate drive chains (the main reason for the shaft-drive experiments) and, worse, the engines swallowed so much dust they wore out in record time.

Some part of the wear may have come from bulk: The WLA’s fighting weight was listed as 540 pounds. The Scout was lighter, but still tipped the scales at nearly 500 pounds. Both bikes would reach the Army’s required 65 mph, but they took a while to get there.

But most of the problem was the bare-bones civilian air

In January, 1942, the Army chose the WLA as its official motorcycle and ordered 31,000 of same to be delivered in two years, which they were.

Indian wasn’t sent home, though. Instead, what with Europe reeling under Nazi bombs and no raw material on hand anyway, the Allies, mostly England, came through with orders for thousands of lend-lease military Scouts.

And there was the Harley WLC, the Canadian Army’s motorcycle; it had the same basics but with variations in saddles, radio mounts and so forth. All the military models could be fitted with scabbards and racks and shields, depending on assignment.

Which was? That, too, depended. None of the models were actually combat vehicles. Sure, there were motorcycles in battle, but that was circumstantial. The official way, the Army Way, was to assign motorcycles to armored divisions where they did courier duty.

Part of this story ends unhappily. About the time H-I) filled the WLA order, the military stopped buying motorcycles, period. The Jeep was doing the job better. The leftovers, the 84Is and XAs included, were declared surplus and sold to civilians, where the shafties proved to be excellent machines, justifying for once the cliche, Ahead Of Their Time.

In part because they were expensive, and in part because there were rancorous debates over the government’s refusal to pay for the tooling and equipment used to make the bikes, neither the 841 nor the XA went into post-war production, an executive decision much more easily criticized now than it would have been then.

But there is a happy ending.

Recall that the motorcycle requires skill to operate. In the service, literally tens of thousands of guys, and more than a few gals, learned to ride. And when they came home, with money, the sport of motorcycling revived beyond anything the makers in the 1930s could have imagined.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

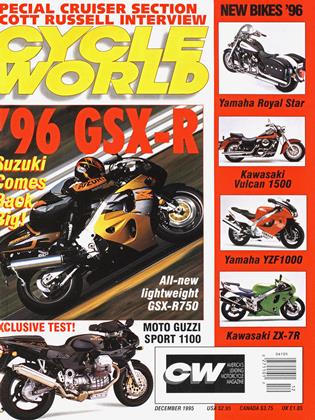

Up Front

Up FrontIndian Reservations

December 1995 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCanadian Map Reading 101

December 1995 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCJohn Britten, 1950-1995

December 1995 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1995 -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Euro-Only Sportbikes For '96

December 1995 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupHonda Steps-Up the Cbr900rr

December 1995