MEXICAN ADVENTURE:

"Chain 'Em To You And Sleep Under 'Em"

ANN B. SIMANTON

CHAIN 'EM to you and sleep under 'em!" The Mexico Insurance agent leaned back in his chair and laughed at his own little joke. "That's motorcycle theft insurance in Mexico!" He was still laughing when I left, liability-only policy in my hand and a sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach. His depressing humor had followed a series of telephone calls, remarks, notes and other unsolicited advice from just about everyone: mother-in-law, dentist, neighbors, friends, down to the boy who sacks my groceries...as soon as they heard about our proposed trip across northern Mexico by motorcycle.

“Carry a gun. At least a knife....” “Did you hear about Bob and Irma Pettigrew? Killed on this little scooter they rented in Bermuda. Yep....”

“You’re crazy, you’ll never come back with those bikes.”

“Let him go, if you must, dear, but no woman has any place running around all over Mexico on a motorcycle....” “Well, I certainly would have thought that you two would have more sense than to....”

By the time I finished with the insurance agent, ran back to the car in a driving rain and looked back at the two Montesa King Scorpions, I was beginning to wonder if maybe we shouldn’t have had more sense. A schoolteacher and a systems analyst with more trail than street experience, planning a trip from Nuevo Laredo to La Paz, Baja California; driving two bikes designed primarily for the dirt—it was beginning to seem as though the whole venture was impossible.

Laredo deepened the general gloom that marked the beginning of the trip. Rain fell steadily as we pulled out of the motel; its cheerful owner waved and shouted after us, “You watch out now, they’ll steal ya blind!” We huddled dejectedly under a gas pump shelter as the man filled the 21/2-gal. cans we were carrying, three for gas and one for water. Oil cans and spare parts rode between the cans in small suitcases given up reluctantly by our two children before they left for camp. We checked over everything once more and decided that there was hardly an unforeseen calamity, short of a serious accident, that could stop us. It was that consoling thought that got us back out into the rain and on our way out of town.

It was still raining when we made our way through bumper-to-bumper traffic across the international bridge and into the wrong parking lot at customs. Two policemen angrily shouted and waved us back to a parking space where several medium-sized boys began loosening bits and pieces on the bikes. We took turns either standing inside in line or sitting outside to mutter threatening things in Spanish to all those who came near our rolling spare parts supply. An hour later, armed with all the necessary permits, we turned to leave, only to find our way blocked by two men in khaki uniforms. They refused to budge. I asked if they had to examine the luggage. No. Why, then, couldn’t we go?

“You have not tip heem.” One of them pointed to the other. I tipped heem. He moved. “And me,” he stood with his arms folded over an enormous stomach, “you tip me, too.” I did, he moved, and so did we, quickly. Nuevo Laredo was fast becoming a collection of our worst fears about the trip.

The road through town passed the market, where the arrival of two truckloads of soldiers added to the general chaos created by the rain and the barely moving mass of motor vehicles, bicycles and pedestrians. A young man darted out from the sidewalk, offering to take us to the exotic pleasures of Boys’ Town, but retreated in confusion when he discovered he wasn’t dealing with two men. In the next block, a man swinging long boards off a truck almost decapitated both of us. We would have considered turning around at that point if it hadn’t been for the prospect of going back through all that.

The highway from Nuevo Laredo to Monterrey is not bad if it’s not raining. The morning rain formed puddles in its uneven surface, puddles which waited there quietly for the next truck or bus to pass and send their entire contents in one sheet over bike and rider. The diesel exhausts of passing vehicles had left a grimy blanket of soot on us that even the water failed to penetrate. Mile after mile of 6-in., multi-legged crawling things made their way across the road; the highway was slippery with them. I slowed down. Falling on a wet highway was bad enough to think about. Falling on a wet highway covered with 6-in. crawling things was more than I wanted to consider.

The sun came out late that afternoon at the same moment that Don’s back tire went flat. Prepared for just such an occasion, we unhooked the tire pump and found that it now had a piece missing. The sun was also in the process of going down, and chances of finding someone to sell us a tire pump 20 miles ahead in Monterrey, late on a Saturday afternoon, were not very good.

Two men cruised by on little Islo 90s, slowed down, and looked us over. After Nuevo Laredo, we felt like carrion being sized up by vultures. They disappeared into the distance, but reappeared a few minutes later with a big black tire pump strapped to one of their bikes. Without a word, they got off, helped change the tube and pumped it up. It took the better part of an hour: parts kept getting lost in the tall grass next to the narrow-shouldered highway. We all shook hands. They refused an offer of payment: they were just glad to be of service to us, they said, “Estamos > para servirles.” It was the first of many times we were to hear this phrase on the trip. We made our way into Monterrey, beginning to suspect that many of the things we had been told about motorcycling in Mexico just weren’t true.

In Monterrey, we chained the bikes together in the courtyard of the motel, contrary to the advice of friends who warned us to take both into the room with us. With the bikes chained together it would have taken six strong men to move them, and it could hardly be done quietly. Still, we slept with one ear tuned to outside motorcycle chain-cutting noises that night.

The next morning it was raining again, but as we left for Saltillo we looked forward to the miles of dry desert we were soon to cross.

They said it was the first time it had rained in that desert for months. Water ran down our backs, through the sand, around the cactus and into the prairie dog holes. We had to shield the openings of the tanks when we filled them from the jerrycans. We finally saw Saltillo squatting ahead of us and in the sun; we drove in, sopping wet and shivering at the mile-high altitude.

In the center of town, going downhill on a one-way street, I glanced back in my mirror and couldn’t find Don anywhere. I pulled over and waited. Two little shoeshine boys ran up. It seemed that the man with the red moto who had the blue helmet had the back tire flat. One of them did a convincing demonstration of this misfortune, hissing like escaping air and bringing his hand sadly down to the sidewalk. They helped me push the bike onto the sidewalk and three blocks back up the hill to where Don sat in a semi-defunct Pemex station, dismantling his chain for the second time in two days.

A crowd was beginning to gather. The old man who owned what was left of the station offered to loan tools. Another came and helped with the tire. Big boys kept little boys from touching anything. The repaired original tube was put back in and pumped up by the old man; he still had an air compressor in the station and wouldn’t let us use our new pump.

The tire went flat again. The crowd groaned and shook their heads. More people came to watch. Out came the tube: four more holes. There were three in the first tube: a careful search turned up a rim defect that combined with sharp tire tools to make all but one of them. The old man appeared with a file for the rim. I set out to find a tire repair place open on a Sunday morning.

Gas stations in Mexico dispense government gas and oil; they don’t fix tires. Tires are repaired at little places called vulcanizadoras. All the gas stations in town were open. The vulcanizadoras were not. After a complete tour of Saltillo, I found one. Since they had no electricity, they vulcanized patches one at a time with a plate of hot coals clamped to the tube. A little boy took the tubes, blew them up to super-size and plunged them into a vat of dirty water, shaking his head as he marked hole after hole. I went outside to sit on the sidewalk, where I was soon joined by a very old man, the owner of the vulcanizadora, who pulled out a rag and began polishing every piece of chrome on the bike. He didn’t, he said, want to see such a beautiful machine dirty.

For the next hour he taught me Spanish words for such things as “valve stem,” and “fork oil,” words that for some reason weren’t included in my college Spanish courses. In between new words he told me gory stories, complete with gestures, about every motorcycle accident that had occurred in or near Saltillo in the last decade. When the little boy came running out with the still-warm tubes, the old man shook my hand, admonished me to be careful, then walked out into the middle of the busy street to stop traffic for me.

Back at the Pemex station, the man on the red moto who had the blue helmet and the flat tire now had about 30 people of various ages in a big circle around him. The repaired tube with the fewest patches was carefully placed in the tire. The crowd was silent as the owner of the station brought out his air hose again. The tire stayed up. Everyone cheered and slapped each other on the back. Hands to shake extended from everywhere. We set out for Torreon with just enough time to make it before dark.

At dusk we pulled into Torreon and got lost. Highways are not badly marked until they make their way through towns: there, the signmakers seem to have lost all sense of responsibility to the motoring public. Two men on Carabelas came to our rescue and led us to the right road. We planned to spend the night in Gomez Palacio, the neighboring town, in a motel that promised a secure courtyard.

It was completely dark when we found the motel and wheeled through the arch into the advertised courtyard, only to find it covered with highlyglazed tiles. It was as though we had driven into someone’s newly-waxed bathroom: we skidded past the office under the startled stares of the management and assorted guests.

The next morning we set out to look for the tools we hadn’t brought, the fork oil we hadn’t brought and the cotter pin that had crumbled into dust at the last tire changing. When the routine maintenance was taken care of, we tiptoed gently across the slick patio and set out on the wrong road to Durango. Half an hour later, back in Gomez Palacio, we found the right road.

The weather, for a change, was beautiful. It encouraged all the cows, goats and burros to come graze along the side of the road. There are no fencing laws in Mexico. Livestock wanders freely and often across the highway. We braked just short of several large, black cows that day. Near Durango we stopped to walk through the deserted movie set used for Tombstone; an entire early western town that sits all alone out in the Mexican desert, not far from the highway.

Durango, like all the other towns we’d passed through, was full of motorcycles of all ages and descriptions. They are mostly small Islos, Carabelas, and Carabela delivery trikes, with occasional old Yamahas, Hondas and homemades. Helmets were rare. Some riders wore construction hard hats. Most of them had nothing on their heads. Entire families would be lined up on one bike, weaving their way in and out of the traffic.

From Durango, a 200-mile mountain drive lay ahead of us. Durango lies at 6300 feet; from there we climbed to over 8000 feet, then descend to sea level in a matter of 40 or 50 miles. We had heard tales of unbanked curves, loose gravel, no railings, sharp dropoffs, overhanging cliffs, wild trucks and abrupt weather changes, but in the morning sun, as we passed through some of the most beautiful mountain scenery we had ever seen, we wondered where all those terrible things we had heard about were.

Around the next curve, that’s where they were. After we hauled one of the bikes out of the ditch back onto the one-lane, gravel-covered, reverse-banked curve, bent the shift lever out with a tire tool and patched the hole in the case with duct tape, we drove on into El Salto, the only real gas stop on the road. Trucks were lined up at every pump: almost all of them were one-piece vehicles. Few semi-trailers, we found out, travel the road because of the tight switchbacks on the descent. These bank back and forth so sharply in places that they can detach the trailer from a larger truck and send the two pieces on their separate way down the mountain.

From El Salto to the highest pass, we ran into many nasty gravel surprises: the road workers would park their trucks in the middle of the road, shovel out an uneven two or three inches of gravel for about 50 yards, then move on to the next blind curve, it seemed, to do it again. Groups of them would stand, leaning on their shovels, while we slithered and tail-wagged our way through.

On the harrow stretches of road we could pass the slower trucks on uphill grades, but then we would soon find ourselves on the downhill side of a careening truck with dubious brakes. The curves were banked now, but railings and shoulders were almost nonexistent. Many of the curves were marked with crosses, in memory of someone who had gone off the edge. Those without crosses bore little signs in Spanish warning us to prepare to meet our God. The possibility was beginning to seem all too real.

From the highest point on the road, we looked out on a sea of white clouds and decided it was well worth the whiteknuckle ride to get there. Then we began to descend. Someone named Amalio had scrawled his name across a sign that proclaimed we were now 2355 meters high and beginning the “Devil’s Backbone.” I didn’t like the sound of that one.

The downhill switchbacks began. For the next two and a half hours, until we came out into the foothills leading to Mazatlan, we never got out of first and second gear. Cliffs overhung the road, so the trucks took to the middle. Wild burros ran alongside, then darted across in front of us. We reached the cloud layer: those clouds, from above so white and fluffy, were gray, cold and wet in the middle. The face masks fogged. Mist stung our eyes. Visibility was barely 15 feet ahead. We were soon soaked to the skin and freezing. There seemed to be no end to the downshifting and braking.

Suddenly we were under the clouds, among the farms of the foothills, face to face with a large flock of goats. A parrot screeched by. The goats scattered at the horn and were soon replaced by chickens and cows; we wound our way through indignant squawks and browneyed stares to the first of three lowwater crossings on the road.

Almost 10 hours after leaving Durango, we crossed the mud flats to Mazatlan, and sat down to feast on giant shrimp and cold Pacifico beer.

At four the next afternoon, we drove the bikes up the ramp onto a swaying ferry. We stayed to watch the ferrymen cable them to the floor, then went upstairs to relax for the evening. The dry, brown mountains of Baja were visible early the next morning. When we docked south of La Paz, Don drove the first bike out and went around to start loading luggage. Mine wouldn’t start.

The trucks were all off the boat now, and I could see the ferrymen waiting, arms folded, for me to move that one last, small item out of the huge hold of the ferry so they could leave. I started pushing. Halfway to the door I looked up to find five unsmiling ferrymen around me. They motioned for me to get on, then pushed the bike at full running speed out and over the ramp. It still refused to start. I got off to push.

A wiry old man stopped me and asked if the cockroach did not want to go. At least he didn’t sing it. I answered through clenched teeth that the cockroach apparently had a fouled spark plug.

“It doesn’t matter,” he said, “get on it and we will teach it to go.”

I looked at his size and obvious years, but got on anyway, since it was still a long walk to the loading area. He clamped his hands onto the back racks and started pushing. Off the concrete ramp, past the customs gate and into the parking lot we flew. It started. We shook hands. I don’t know who was more pleased.

Twelve miles later we parked the bikes among the flour sacks in a grocery warehouse next to a little hotel, and began sorting out luggage. Few of the dire predictions for the trip had proved to be true. On the contrary, as motorcyclists, we were welcomed everywhere we went in Mexico. People gave us parts, loaned us tools, and helped willingly without being asked. The reason given was always the same: “Estamos para servirles.”

We arrived in La Paz with an impression of Mexico that we could never have had from a car. We arrived in La Paz with bruises and sunburn we wouldn’t have had in a car.

But we’d do it all again. SI

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

November 1973 By Joe Parkhurst -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1973 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeedback

November 1973 -

The Scene

November 1973 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Competition

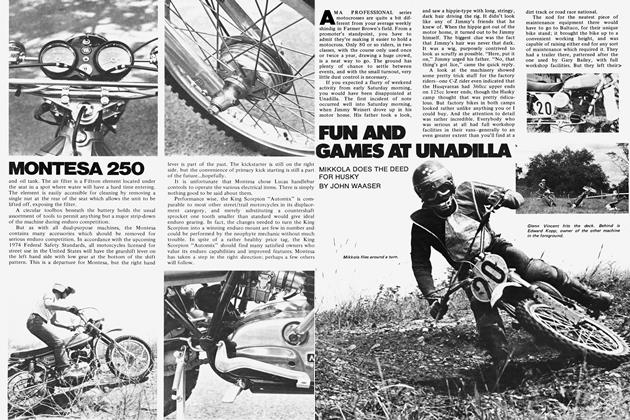

CompetitionFun And Games At Unadilla

November 1973 By John Waaser -

Competition

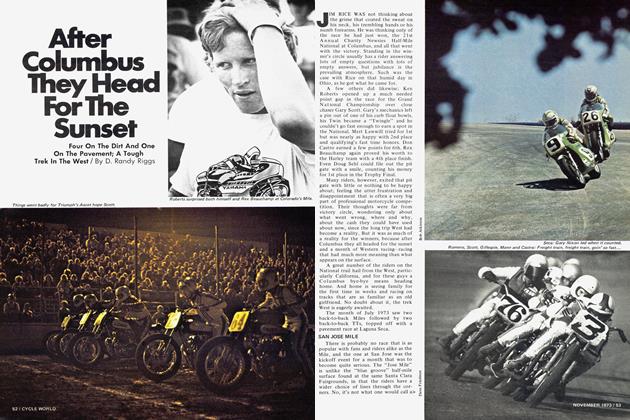

CompetitionAfter Columbus They Head For the Sunset

November 1973 By D. Randy Riggs