RACE WATCH

Making Every Penny count

Studying the business of Superbike racing at Miller Motorsports Park

KEVIN CAMERON

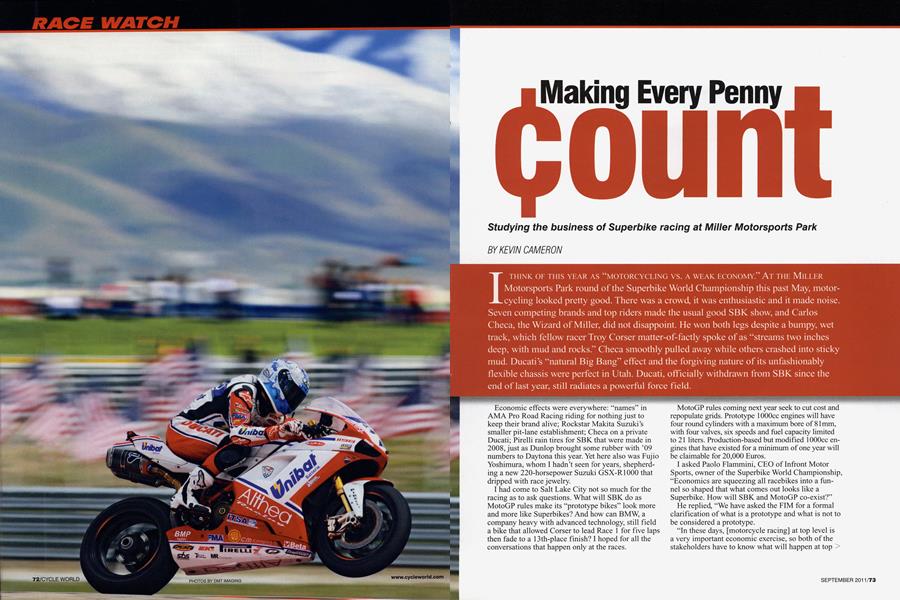

I THINK OF THIS YEAR AS “MOTORCYCLING VS. A WEAK ECONOMY.” AT THE MILLER Motorsports Park round of the Superbike World Championship this past May, motorcycling looked pretty good. There was a crowd, it was enthusiastic and it made noise. Seven competing brands and top riders made the usual good SBK show, and Carlos Checa, the Wizard of Miller, did not disappoint. He won both legs despite a bumpy, wet track, which fellow racer Troy Corser matter-of-factly spoke of as “streams two inches deep, with mud and rocks.” Checa smoothly pulled away while others crashed into sticky mud. Ducati’s “natural Big Bang” effect and the forgiving nature of its unfashionably flexible chassis were perfect in Utah. Ducati, officially withdrawn from SBK since the end of last year, still radiates a powerful force field.

Economic effects were everywhere: “names” in AMA Pro Road Racing riding for nothing just to keep their brand alive; Rockstar Makita Suzuki’s smaller pit-lane establishment; Checa on a private Ducati; Pirelli rain tires for SBK that were made in 2008, just as Dunlop brought some rubber with ’09 numbers to Daytona this year. Yet here also was Fujio Yoshimura, whom I hadn’t seen for years, shepherding a new 220-horsepower Suzuki GSX-R1000 that dripped with race jewelry.

I had come to Salt Lake City not so much for the racing as to ask questions. What will SBK do as MotoGP rules make its “prototype bikes” look more and more like Superbikes? And how can BMW, a company heavy with advanced technology, still field a bike that allowed Corser to lead Race 1 for five laps then fade to a 13th-place finish? I hoped for all the conversations that happen only at the races.

MotoGP rules coming next year seek to cut cost and repopulate grids. Prototype lOOOcc engines will have four round cylinders with a maximum bore of 81mm, with four valves, six speeds and fuel capacity limited to 21 liters. Production-based but modified 1 OOOcc engines that have existed for a minimum of one year will be claimable for 20,000 Euros.

I asked Paolo Flammini, CEO of Infront Motor Sports, owner of the Superbike World Championship, “Economics are squeezing all racebikes into a funnel so shaped that what comes out looks like a Superbike. How will SBK and MotoGP co-exist?”

He replied, “We have asked the FIM for a formal clarification of what is a prototype and what is not to be considered a prototype.

“In these days, [motorcycle racing] at top level is a very important economic exercise, so both of the stakeholders have to know what will happen at top > level. Our regulations have been stable for the last seven years now, and they will remain stable for the reasonably foreseeable future. The current rules could be absolutely fine, but the FIM has to say what the limit is between the prototype bike and production bike.”

When I returned home after the Miller races, there was news that SBK might be for sale, and that Dorna, the MotoGP rights-holder, might be a buyer. Dog eat dog?

What I didn’t want from BMW was corporate-speak: “Our engineers are working on a broad front to improve all aspects of the motorcycle, and we hope soon to reap the fruits of their efforts.” It’s been two years, guys! Where’s the problem?

It was our good fortune to be given good talkers: riders Corser and Leon Haslam, and engineer Bernhard Gobmeier. They revealed that BMW’s engine-braking control system operates only over a narrow range of grip. One week, if grip remains consistent, the S1000RR works well. At the next circuit, grip may be different or if, as at Miller, it rains and the system is pushed out of its operating range, function is lost. Haslam noted that they can’t really do full chassis development until the engine-braking system is made right. The chassis also remains on the stiff side and engine delivery harsh.

Haslam spoke of a need to maintain rear braking as part of the enginebraking problem. If rear braking is lost, he noted, the rear will rise and overall braking will suffer. The rear caliper is attached to the swingarm, so its torque tends to compress the rear suspension. This, plus natural brake dive at the front, lowers the center of mass and allows the rider to brake harder. Do we call this “personal ride-height control?”

The wonderful irony is that BMW— for years irrelevant to the sportbike scene—is fast replacing the GSX-R as the privateer’s choice. That is because it is the most nearly race-ready of all bikes and not lacking the 20 hp that the others need. It’s been shown that a good rider on a basically stock BMW can get within a second of AMA’s top men.

Gobmeier said, “People working on this project, some are coming from the motorcycle side, some from the car side. Car electronics are 10-15 years sooner, and what we use came from F-1. Over five years, we added the features necessary for a motorcycle.”

Here again, irony of history: BMW may have slowed its Superbike program by developing its own electronics rather than buying Marelli or MoTeC, but then they stole a sales march on the Japanese by making traction control and throttleby-wire into admired selling points of the S1000RR.

Gobmeier continued, “We are much, much more flexible in incorporating functions into our system. We have the electronic capabilities in-house to do this within a week or two weeks.”

He spoke of braking: “Once you go all the way down with the throttle, you have less gas speed in the intake, a worse mixture in the combustion chamber, and you have misfire. This becomes also irregular torque at the rear wheel [which can destroy rear grip during comer entry]. You need to open the throttle in such a way that the engine is [again] running smoothly. In MotoGP, you have more freedom [to do this] but in SBK, you cannot modify the production throttle body.”

I also talked with Ronald Ten Kate, the Dutchman who mns Team Castrol Honda. His uncle’s company, Ten Kate Motorcycles, based in the Netherlands, has built a business on racing parts and services. Ten Kate spoke of economic effects on racing tires.

“In other times,” he began, “the tire people would want to replace a tire that has been hot once [heat cycling can cause a permanent loss of tire properties]. Now, with a tire that has been twice in the warmer, they say ‘It’ll be fine.’” Ten Kate knew about Dunlop’s fronttire problems at this spring’s Daytona 200 and added that SBK-spec Pirellis had chunked at Phillip Island in Australia. “I am talking about big pieces coming out,” he said, “not little blisters.”

I asked if a tire maker might, for cost reasons, postpone running a standard pre-season Daytona simulation on a test drum. He replied, “The money will go first to Formula One and then other series must divide what is left.”

Honda has pestered Ten Kate to cut costs. “I asked them, ‘Shall I ride a bicycle to the circuit instead of driving a rental car? Shall the team sleep in a tent at the circuit? Sit on the wing of discount airlines?’ Now, there is no longer talk of this kind.”

Ten Kate also said that the company’s new Moto2 chassis would be tested on the following Monday, and that it would sell for half the price of what is now on the market—108,000 Euros. Ten Kate has made this chassis because its sees a business opportunity, not to race itself.

“I think Suter and Moriwaki have been talking to each other,” he smiled.

Superpole took place in cold rain and was a stunning showcase for what has been achieved with rain tires. Amazing angles of lean and braking hard enough to provoke instability (meaning riders were able to unload the rear tire) were the results.

I spoke also with Giorgio Barbier, who manages Pirelli’s racing program.

I asked him about the use of silica as a tread compound reinforcing agent (carbon black has been and remains the principal reinforcing agent). Michelin,

I knew, had begun to use soft rain compounds on dry tires 20 years ago. Barbier spoke of his early days in the company, when F-l rain tires included paraffinic oils in the compound.

“This appeared on the tread as little drops [tire men call this ‘sweating’],” he said. “After one month, so much oil was lost that you had to scrap the tire. Silica was a revolution in rain performance.

It creates with the polymer [the elastic molecules of rubber] a better cohesion. It could encase the oil [it was soft but strong]. This was an improvement, even from the standpoint of wear. At first, silica didn’t work well at higher temperatures.”

As Barbier spoke, I remembered 2004, when MotoGP Bridgestones were fast in cool mornings and slower in sunny afternoons. “New materials came from this technology,” he said.

Barbier spoke of the electronics revolution. “[Marco] Melandri said he couldn’t heat up his tire in MotoGP, and I think this is because he cannot make himself open the throttle [at full lean].

In MotoGP, if you are unable to trust the electronics, you cannot be fast.”

I immediately thought of others with the same problem. Now, I understand that tire compounds are being made to suit full use of electronic aids. In 2007, Yamaha’s trackside recording equipment indicated that the traction control of Casey Stoner’s Ducati was already cycling with the bike at full lean angle. That indicates MotoGP bikes have enough traction to accelerate quite hard even when far over. If a rider does not use this, his tire will never reach operating temperature and his career in that series is over. As was Checa’s in MotoGP.

Barbier said, “Pirelli has made its tires to suit the seven makers competing and have not rapidly changed the tires. Thus, it is easy to see when one of the factories makes its chassis stiffer because that maker’s riders immediately complain that their tires are not working as well. Then, the makers come back to ‘normal’ on chassis stiffness. If you consider the tire as part of the suspension of the bike, our job is to make pneumatic springs.”

Rider views are always interesting. Reigning AMA Pro American SuperBike Champion Josh Hayes said the Pirellis may lose traction as they age, but their side grip does not fade. Dunlops, he continued, do lose grip permanently in a heat cycle—if the tire has been made hot, it will not recover when it cools.

In all of our conversations, the subject of assuring the flow of new riders came up. Part of this is something Flammini had said earlier: “The very young people today are not as passionate as we were when we were kids.” This means that those who do enter the sport need more help, and manufacturers, race-sanctioning bodies and tire companies are quietly helping those with whom they hope to have enduring relationships.

Why is Carlos Checa the “Wizard of Miller?” Technology aside, he was reborn as a great rider when offered a second career by the Superbike World Championship.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

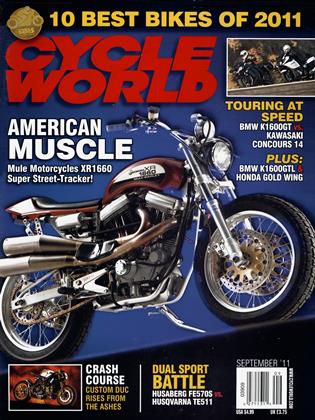

Up Front

Up FrontThe Ten Rest 2011

SEPTEMBER 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

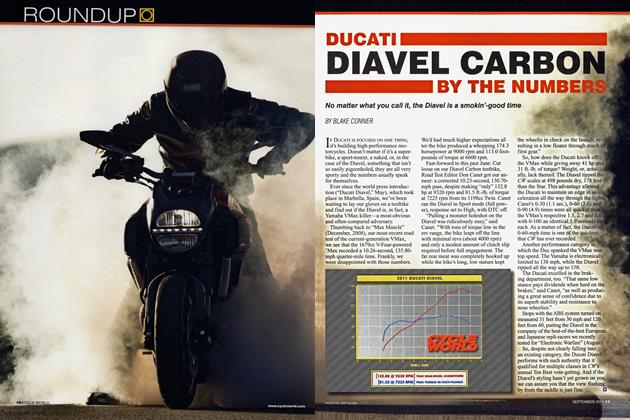

RoundupDucati Diavel Carbon By the Numbers

SEPTEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

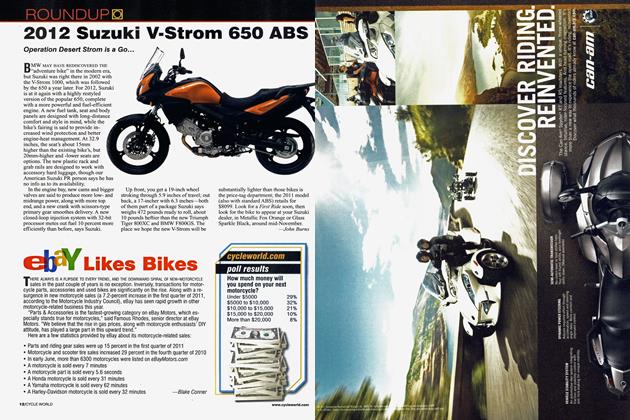

Roundup2012 Suzuki V-Strom 650 Abs

SEPTEMBER 2011 By John Burns -

Roundup

RoundupEbay Likes Bikes

SEPTEMBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago September 1986

SEPTEMBER 2011 By John Burns -

Roundup

RoundupMv Agusta F3

SEPTEMBER 2011 By Bruno Deprato