Clipboard

RAOE WATCH

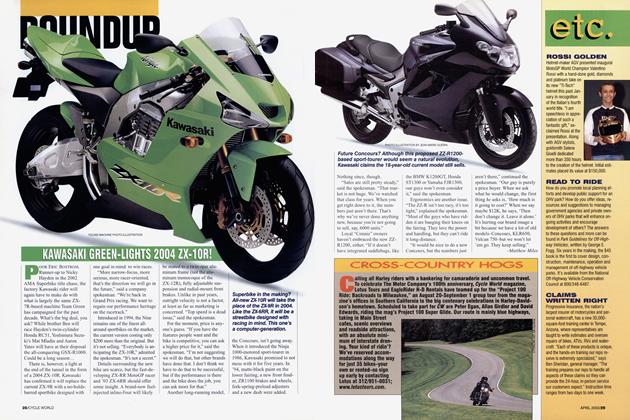

Max moves on

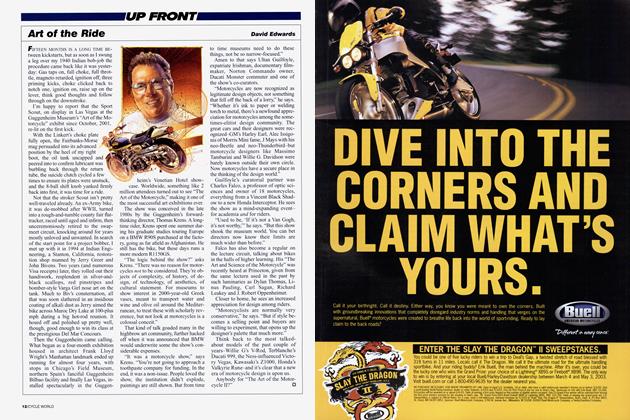

Four-time 250cc World Champion Max Biaggi isn’t doing too badly for a guy who only learned how to operate a motorcycle clutch at the age of 18.

What?! Yes, it’s true. Biaggi loved soccer, thought he might even pursue a career in the sport, and was only given his first motorcycle by his father on birthday number 18.

“It is a good story,” Biaggi says with a wry smile. “Maybe not so good for me, but for you it is a very good story. I went with my friend to pick up my motorcycle, but I didn’t know how to use a clutch. So I had to jump on the back of the bike with my friend riding!”

Biaggi the soccer player caught on quickly. After giving the racetrack a try “for fun” on a production 125, he found riding came pretty naturally. “I just needed to find the line,” he says, in a rather tremendous understatement.

He found it. The next year, Biaggi was Italian 125cc Champion, then European 250cc Champion at 20, took his inaugural 250cc Grand Prix win at 21 and earned his first 250cc world title at 22.

After three more titles-two with Aprilia, one with Honda-he moved to the top class in 1998 with Yamaha on a YZR500, and has finished second three times, once > in his debut year to five-time champ Mick Doohan, and twice to Italian archrival Valentino Rossi. It hasn’t exactly escaped Biaggi’s attention that he’s been beaten by men riding Hondas-very talented men, to be sure, but on Hondas nonetheless. After spending last season developing Yamaha’s four-stroke YZRM l into a race-winner, Biaggi sought to stack the deck more in his favor, signing up with the Honda Pons team to ride the RC21IV vacated by Alex Barros.

“Now, I can race” the 31-year-old says. “Last season with the Yamaha, nothing was ever the same.”

Still, he did manage to win two races, something he credits largely to a better engine-management system, particularly as it affects the computer-controlled engine braking.

“At the end, the bike became what it should have been early in the season,” he says. “Imagine the Honda guys: They pick up the bike and maybe once or twice a year they get new parts. Our bike, from when we started the season to when we finished, it was a completely different bike, another engine, another chassis, another management system. At many races, I had two different chassis. Normally, you don’t do this. It’s not so easy to keep all the parameters in my mind and to go racing and think about how to go fast. The job was very big. Sometimes, I started races and I wasn’t competitive. It is hard when you know this.”

It was this struggle that Biaggi says made him “very, very tired,” and motivated him to pursue other opportunities in the paddock. In fact, Biaggi knew months before the end of the season that > he was going to leave Yamaha. Did he talk to anyone other than Honda?

“Sure, I had meetings with other manufacturers, because it is good to say, ‘I’m listening,’” he states. “But in the end I chose Honda, because it will give me what I want. I want to be on a good team, on a good bike, right away. Maybe the Ducati can be good, but the bike needs to ‘grow up.’Aprilia is the same.”

Was it a bother that AMA Superbike Champion Nicky Hayden walked right into the factory seat as teammate to Rossi? “It is good for him,” Biaggi says. “He is in the best possible position to prove himself. If he is a good rider, and I think he is, he can show his potential. He’s a nice guy. I met him at the AMA Supercross in Anaheim. But, anyway, for me to be on that team, it would not be possible.”

Biaggi refers, of course, to the heated rivalry he and Rossi have maintained even before they began racing head-tohead in the 500cc class in 2000.

Biaggi knows that because he isn’t on the full-factory squad, he may not be getting the latest and best equipment from Honda, but nonetheless feels better about his chances at racing for victory and adding a fifth world championship to his résúmé.

“I know that we will not have what the factory team has,” he says, adding that even his Honda Pons teammate Tohru Ukawa and Gresini Honda’s Daijiro Kato will likely have better equipment. “But what I have, it will be enough.”

It was certainly enough for Brazilian veteran Barros, who was suddenly racing with Rossi for the lead once he was allowed to trade-in his NSR500 twostroke for a V-Five at the last few rounds of the 2002 season. Barros and other VFivers showed that in addition to handling well, the Honda a had pretty clear power advantage.

“Yes, they were usually like 5 mph faster in top speed,” Biaggi says.

But your Yamaha usually was faster than the Suzukis, right?

“I don’t want to compete with Suzuki,” he says plainly. “I want to compete for the lead.”

So, what were Biaggi’s first impressions of the Honda?

“It feels light and small, very compact,” he says. “The front end is solid, much more so than any other bike. When you jump from one bike to the other, it is very clear. It is very good for me.

“I am very relaxed,” he continues. “This year, I approach the championship with this in mind.” -Mark Hoyer

Jim Feuling 1945-2002

Jim Feuiing, land-speed-record holder, creator of the Harley-Davidson-based Feuiing W-3 streetbike and a veteran engineering consultant, died of cancer last December. He was 57.

Feuiing had built up a substantial business supplying consulting services to major motorcycle, car and aircraft manufacturers, as well as designing and manufacturing racing and high-performance parts. He had many patents and was a prolific speaker, having made presentations to the Society of Automotive Engineers, the Superflow Conference and other engineering societies.

Motorcyclists associate his name with the Feuiing W-3 cruiser-a three-cylinder > machine based on Harley components. Like the W-3 built by motorcycle pioneer Glenn Curtiss in 1909, the Feuling Triple employs a master rod for its center cylinder, with link rods attached to its big-end for the front and rear cylinders. Feuling also produced and sold highperformance twoand four-valve cylinder-head kits for Harley-Davidsons, as well as cylinder heads and other special assemblies for automotive use.

His particular specialty was proving the value of pragmatic solutions to academic engineers who insisted these solutions were impossible. Is your new billion-dollar motorcycleor auto-engine program stalled by mystery overheating? Counter to accepted practice, he’d make your exhaust valve smaller, then increase its flow capacity by 30 percent. With less port and valve exposed to hot gas, and with that gas leaving the cylinder faster, head temperature would fall nicely. This kind of simple solution was one of his stocks in trade. The list of his consulting contracts was long, and included all the familiar big names. He was comfortable in 14th-floor Detroit boardrooms (or those in Milwaukee) because he had complete confidence in his ability to deliver workable technologies.

Feuling was a long-time land-speed competitor at Bonneville and elsewhere. Under contract to General Motors, he developed a high-performance top-end for the Oldsmobile Quad Four engine, which was used subsequently to set many records. Other achievements include a controversial three-wheeled “motorcycle” mark at 332.103-mph, set with a front-drive automotive streamliner powered by a 414-cubic-inch Chevy sprintcar engine-and running only one of the normal two rear wheels so that it would fit the letter, if not the spirit, of the rules.

It was things such as this that cause not all his former associates to remember him fondly, but they do agree that Feuling was a highly intelligent person of great energy and wide interests. Like physicist Richard Feynman, he wanted all good ideas to have been his own-his business relationships sometimes ended in court. He saw himself-schooled in hot-rodding and hands-on experimental mechanical engineering-as the last of his breed, a lone warrior in single combat with the new bureaucracy of theoreticians and “screen-jockeys” who were crucially lacking in ordinary physical intuition.

The man is gone, but his ideas persist, likely in a vehicle on or in which you have recently ridden. -Kevin Cameron