Nothing to Lose

RACE WATCH

KEVIN CAMERON

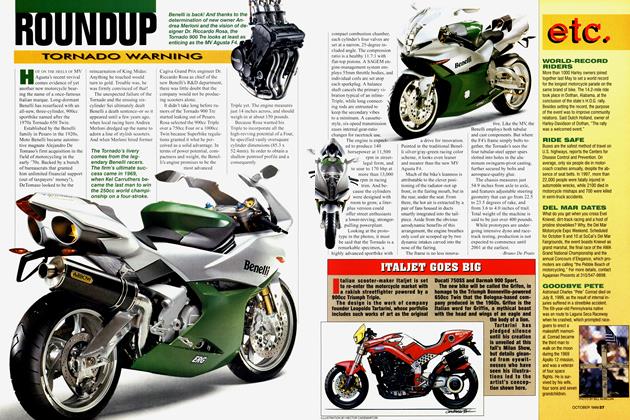

THE WORLD SUPERBIKE ROUND AT LAGUNA SECA IS AN anomaly. Although we Americans love to see our national stars win and place well there, it is all but irrelevant to the World Superbike Championship. Our riders contest only this one race, as wild-card entries, and are not in the title chase. The Europeans happily let them go, concentrating instead on their race with each other. That said, on to the results.

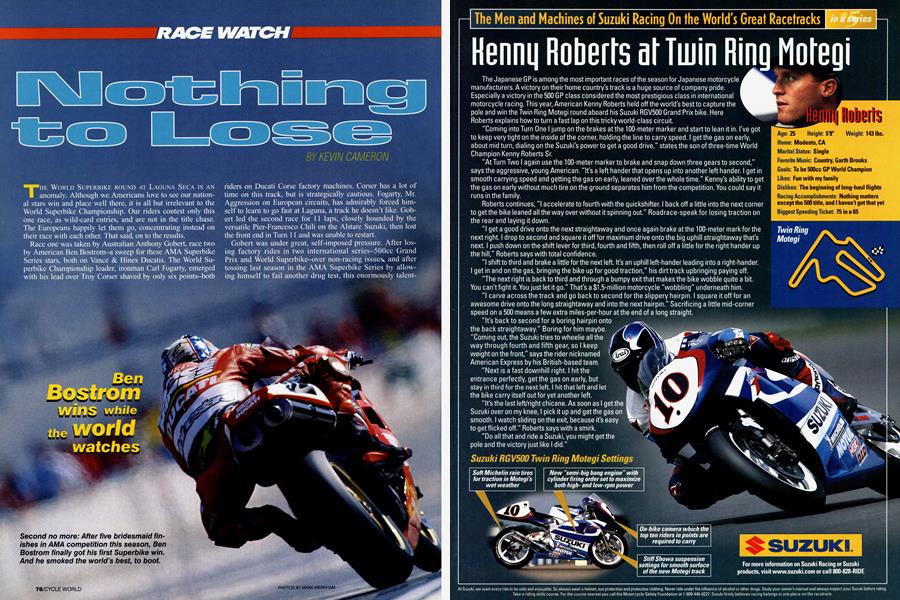

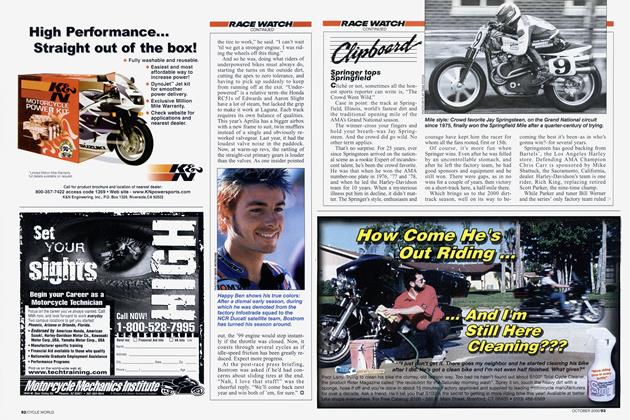

Race one was taken by Australian Anthony Gobert, race two by American Ben Bostrom-a sweep for these AMA Superbike Series stars, both on Vance & Hines Ducatis. The World Superbike Championship leader, ironman Carl Fogarty, emerged with his lead over Troy Corser shaved by only six points-both riders on Ducati Corse factory machines. Corser has a lot of time on this track, but is strategically cautious. Fogarty, Mr. Aggression on European circuits, has admirably forced himself to learn to go fast at Laguna, a track he doesn't like. Gobert led the second race for 11 laps, closely hounded by the versatile Pier-Francesco Chili on the Alstare Suzuki, then lost the front end in Turn 11 and was unable to restart.

Gobert was under great, self-imposed pressure. After losing factory rides in two international series-500cc Grand Prix and World Superbike-over non-racing issues, and after tossing last season in the AMA Superbike Series by allowing himself to fail another drug test, this enormously talented and respected young man was given another go by his gutsy sponsor, Terry Vance. Yearning to show the world that he can beat all comers, Gobert must win pretty much everything to retain any chance of a return to the world stage. He has to prove that he is not just a flaky party-goer, incapable of championship-winning self-discipline.

Ben Bostrom wins while the World watches

Still chubby from off-season (and during-season?) pleasures, he showed up a day late at the Loudon, New Hampshire, AMA national in June. Then, in four action-packed minutes near the end of Saturday qualifying, he set three new lap records in a row. This is the stuff of dreams. Despite his devil-may-care disregard for everything including his own talent, the man goes supremely well on a motorcycle.

Other American wild-card entries at Laguna were Jamie Hacking, on the new Yamaha YZF-R7, Eric Bostrom on an American Honda RC45, and Mike Smith on the European-backed White Endurance RC45.

While Gobert held point in race one, Ben Bostrom spent every lap but the last in third place, behind Akira Yanagawa’s Kawasaki. Bostrom closed up with apparent ease three times, indicating that he would likely spring a last-lap surprise. And he did, diving under the Japanese pilot at the entry to the Corkscrew on the last lap, and holding second to the flag. Behind Yanagawa came Colin Edwards, Fogarty, Corser, Chili, Hacking, Aaron Slight and Eric Bostrom.

Roadracing is not a test of the easily measured variables you read about in road tests: horsepower, quarter-mile times, power-to-weight ratios. Those things are important, but none of them wins races. Races are won by machines that steer off of corners while hooking up rather than spinning, and which are gentler to tires than the competition. These qualities come from setup-the adjustment of chassis variables, their integration with the rider’s style and correct choice of tires.

Racing rubber is unlike street rubber. For maximum grip, the best mix of properties is achieved in rubber that is incompletely cured. Racing heats tires above boiling-water temperature, and this resumes the cure > process-chemical reactions in the rubber that gradually increase its hardness but ultimately reduce its grip. Tire properties change irreversibly during use. Traction is poor when the rubber is cold and hard, which is why tire-warmers are used before practice and the races. Once fully heated by track use, the rubber becomes soft enough to grip well, tough enough to last a while. As time passes, its properties deteriorate. After 10 or 20 laps, the tire “goes off”—it loses its peak grip, and nothing will bring it back.

Tire grip and durability tend to be mutually exclusive. A soft rubber compound grips well but dies young. An ultra-soft qualifying, or “Q-tire,” grips best on laps two, three and maybe four. After that, it’s useless. A race tire takes longer to “come in,” but when it does, it may display peak grip for laps three through 15, while a harder tire might be slower on laps one through 10, but better than the softer tire for laps 12 to the end. Finding out how tires will act on a given track is one of the many goals of practice. There are usually several tire choices available-a combination recommended by the tire-maker for the particular track, and one or more alternates, either softer or harder. One especially powerful strategy is to find a bike setup that makes a softer, grip> pier, but more vulnerable tire last. Even the most experienced riders and technicians make mistakes with tires.

It is the tire engineer’s job to produce tires whose period of peak grip is long enough for a top rider to break away from competitors and establish an unassailable lead. The rider’s style also affects tire life. A “go-for-it” rider, spinning and sliding, looks good early but loses positions as his tires go off. A rider whose style centers on high corner speed-like Chili-is more vulnerable to tire condition than is a rider who turns less hard, using the latter half of the turn as a minidragstrip for acceleration. There’s more to this business than just turning the throttle.

So much for complexity. Ducati won both races at Laguna Seca, holds first and second place in the World Superbike title chase and has won most of the championships in the history of the series. Is that because Twins are allowed lOOOcc, and Fours only 750cc? This displacement difference is intended as a horsepower equalizer, to compensate for the Fours’ ability to rev higher than the Twins. If the extra displacement is too great an advantage, as some now contend, why is it the four-cylinder bikes have a clear horsepower and top-speed advantage? What the Ducatis do best is accelerate off of the lowand medium-speed corners that abound on the world championship circuit-and this is all part-throttle performance. Offcorner acceleration is not a test of maximum power. It is a test of power smoothness and chassis setup.

Every factory has a different idea of what is important. Ducati accepts a 6mph top-speed disadvantage (the equivalent of 15-20 horsepower) in return for smooth, traction-nurturing acceleration. The bikes are pushing (understeering) more now, with more power (160 bhp), and that poses a problem on slower circuits. Honda, in the RC45 V-Four, has combined the highest power in the class (188 bhp) with smooth throttle control-and the quirkiest, rider-challenging handling there is. Honda needs a new motorcycle, and may in fact race a Twin next season. Aprilia, the newcomer with its 60-degree RSV Mille (say Mee-lay) V-Twin, has a bike that already accelerates well and turns on the front end. That should be no surprise-Aprilia has a huge experience base from its many 250cc GP championships. Aprilia claims 145 bhp at 11,000 rpm, and has already been through one round of updates, nearly doubling airbox volume. Suzuki’s current GSX-R750 is not smooth coming on-throttle, but has good power. Kawasaki, the only team still running carburetors, has smooth

throttle-up, strong, fairly wide power and a good but not super all-around setup. Yamaha’s YZF-R7, with the newest design, naturally has the worst problems to overcome, but it snaprolls from side-to-side like nothing else and likely will mature into the best 750 in the series. Meanwhile, Noriyuki Haga, the man who astounded us last year with his bold, slashing corner lines, must struggle with his R7’s braking instability and unsettling general twitchiness.

Engine sounds contain information. The Aprilia’s valve gear makes more noise than its exhaust. This is a race engine, developed by Cosworth, quite different from that of the production Mille. When I asked a staffer what was different, he replied zf/zfo-everything. The valve noise is the reversals in the drive as the cam lobes snap past max lift, with about 13,000 rpm of extra valve-spring pressure on them. On the track, there is also loud piston noise audible over the throaty Twin sound. Rider Peter Goddard put this bike fifth in Superpole qualifying-a fine achievement in the bike’s first season.

The Suzukis sounded “cammy,” gobbling irregularly as they warmedup at 1300 rpm, but the Hondas and Kawasakis would idle right down like streetbikes. The Honda’s deep growl reveals both its V-Four architecture and its gear-driven cams. High-lift, > long-duration cams make peak power, but they also cause rough idle and weak running off the bottom. On the track, the Suzuki and Yamaha riders were having to delay throttle opening after turns because of this irregular running, which sounded like the engine’s voice had become falsetto. To get both peak power and bottom smoothness requires high-lift, shortduration cams, but these produce violent valve accelerations that break valves and springs. Development solves all problems-given time, intelligence and enough money.

Fuel injection doesn’t make life easy. It’s a test of character. Instead of the usual carburetor systems, substitute injector on-time, phase, multi-injector bias and cylinder-to-cylinder stagger. Good throttle response is the result of endless testing. The factories and teams that have put in the time are the ones with the results-Ducati and Honda. Suzuki and Yamaha both have catching up to do. Ducati now uses three injectors in each of its two 60mm intake stacks. There is a small vernier injector down near the valve, a big injector at the top and another fair-sized one at the bottom. The vernier injector may be partially responsible for Ducati’s ultra-smooth throttle-up, while the other bottom injector supplies fuel volume as power rises, and the top injector takes over at higher revs, when the fuel needs more time-of-flight in which to evaporate. Human beings had to program everything this system does-there is no Microsoft EZ-Tune software package.

These machines are beautiful in themselves. The long welds on the Aprilia’s shapely aluminum chassis and swingarm are superhumanly wonderful. Robots? CNC-milled parts such as foot controls, fork crowns and fork bottoms gleam, as perfect as ideas. Carbon-fiber airboxes, vacuumautoclaved onto machined molds, look light, stiff and expensive. They are. Electronics packages-as with aircraft, now nearly doubling the price of the machines-spread their nerve endings everywhere. I observed a prepractice check by a laptop-armed Yamaha technician (every team has its own information-technology specialist); looking at the screen, he successively pushed the front suspension down, worked the brake lever and ran a hand across the array of infrared sensors aimed at the rear tire. We are go for launch.

Walking around the circuit or watching the TV feed, you can compare rider styles. Gobert oozes-he is the ultimate in smooth motion, making tires grip and drive. The Honda men take a tight line at the bottom of the Corkscrew, and have to steer the back with the throttle because they are too rear-heavy to steer on the front. The Ducatis take a wider line, steering more on the front wheel, and end up at about the same place on the track-but going a bit faster. Chili uses extreme lean angles and high apex speed on his Suzuki-the legacy of 250cc GP racing, where there’s less power for acceleration. Of the race-two duel between Gobert and Chili, the Italian commented, “Gobert tries to close the inside.” This is to prevent Chili’s higher speed at that point from allowing him to pass. “He can open the gas earlier than me,” Chili added. Indeed, Gobert is a master of the Ducati’s superior throttle-up smoothness.

In race two, Ben Bostrom took over from Chili two laps after Gobert’s lap12 crash, and held the lead to the end. After many frustrating second-place finishes in AMA competition this season, this was a fine way to assert his maturity. Corser, after many laps in third, displaced Chili, whose tires > were fading, for second place. After Chili in third came Fogarty, Edwards, Slight, Eric Bostrom, Gregorio Lavilla, Goddard and Haga.

There is a new way to mount brake calipers. Formerly, each fork bottom carried a prong, projecting upward and backward, to which its brake caliper is bolted by one end. In the new system, originated by Aprilia on its 250s and now used by the factory Ducatis and Kawasakis as well, there is instead a broad blade, extending straight back from each fork bottom, bolting to the caliper at both ends. This is said to prevent wedge-wear of pads, as that narrow prong is twisted by brake force. It may also help prevent brake-pad knock-back in bumpy corners or during headshake.

Handling and performance aren’t the same. A motorcycle that throttlesteers easily on the rear wheel handles well-that is, it is easily controlled by its rider. Yet because its rear tire spins rather than grips, its performance (in terms of acceleration) is poor. Thus, the goals of handling and performance are opposed to each other. The Honda RC45 is the classic case here-it can be made either to steer or hook up, but seldom both. Ducati has the most experience at the difficult job of pushing performance forward a notch, then doctoring the handling enough to make the resulting problems manageable again, then nudging performance again, and so on. There is at present no way to go straight to a correct solution by design-no one knows enough! It will be fascinating to see how close Cagiva will be when its 750cc MV Agusta F4 debuts in World Superbike racing sometime in the future.

The squat-and-push problem remains central; bikes with poor rear geometry squat under the combined loads of cornering and acceleration. This slight rearward pitch transfers weight off the front wheel, causing it to push, or understeer. This push is tremendously frustrating to a rider because the harder he gasses it off turns, the worse the bike steers, running wide, off-line. In-shape riders try to compensate by pulling themselves forward on their bikes, but it’s often not enough. The quick-and-dirty fix for this has been to use a rear spring so stiff that squat is impossible-but a stiff setup kills tire life and causes skating. Better to change geometryif the homologated stock chassis permits-so that engine power, generating lift force through drive-chain tension, cancels the squat. This allows a softer spring to be used, improving tire grip and life. You can trace the history of this through the increase in swingarm droop in recent years. At the moment, you can also see that Aprilia has its swingarm pivot at the limit of its upward adjustment. Everyone is looking for that perfect setup that gives good steering, doesn’t abuse tires, yet hooks up and goes forward. Because tires, engines, riders and circuits change, this search goes on forever.

To the Europeans, Laguna Seca was a risky skirmish, a chance to lose everything, a holding action. For Anthony

Gobert, it loomed as a key step in his journey back to international racing. Will he be on a Ducati next year in World Superbike? If so, whose? For Ben Bostrom, it was proof that he can rise above his seemingly endless string of second places. And what a first! For the American spectators (a claimed 69,000 over the three days), it was all gravy.