No mo' Evo

UP FRONT

David Edwards

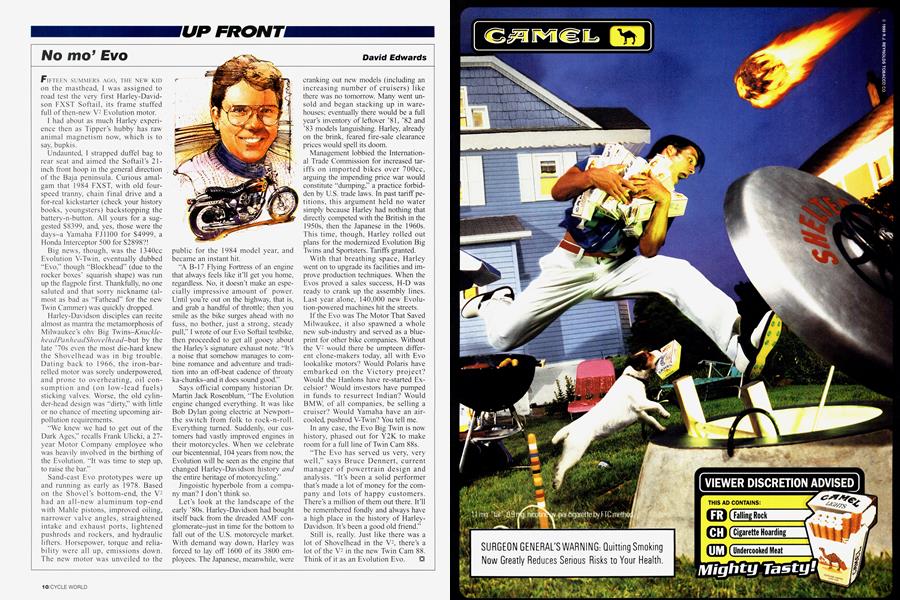

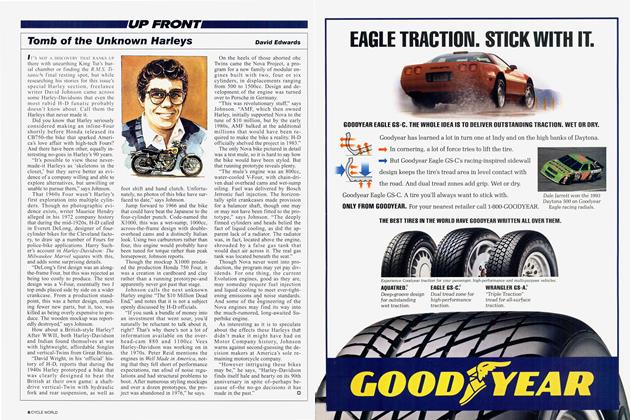

FIFTEEN SUMMERS AGO, THE NEW KID on the masthead, I was assigned to road test the very first Harley-Davidson FXST Softail, its frame stuffed full of then-new V2 Evolution motor.

I had about as much Harley experience then as Tipper’s hubby has raw animal magnetism now, which is to say, bupkis.

Undaunted, I strapped duffel bag to rear seat and aimed the Softail’s 21inch front hoop in the general direction of the Baja peninsula. Curious amalgam that 1984 FXST, with old fourspeed tranny, chain final drive and a for-real kickstarter (check your history books, youngsters) backstopping the battery-n-button. All yours for a suggested $8399, and, yes, those were the days-a Yamaha FJ 1100 for $4999, a Honda Interceptor 500 for $2898?!

Big news, though, was the 1340cc Evolution V-Twin, eventually dubbed “Evo,” though “Blockhead” (due to the rocker boxes’ squarish shape) was run up the flagpole first. Thankfully, no one saluted and that sorry nickname (almost as bad as “Fathead” for the new Twin Cammer) was quickly dropped.

Harley-Davidson disciples can recite almost as mantra the metamorphosis of Milwaukee’s ohv Big Twins-Xm/cA7eheadPanheadShovelhead-buX by the late ’70s even the most die-hard knew the Shovelhead was in big trouble. Dating back to 1966, the iron-barrelled motor was sorely underpowered, and prone to overheating, oil consumption and (on low-lead fuels) sticking valves. Worse, the old cylinder-head design was “dirty,” with little or no chance of meeting upcoming airpollution requirements.

“We knew we had to get out of the Dark Ages,” recalls Frank Ulicki, a 27year Motor Company employee who was heavily involved in the birthing of the Evolution. “It was time to step up, to raise the bar.”

Sand-cast Evo prototypes were up and running as early as 1978. Based on the Shovel’s bottom-end, the V2 had an all-new aluminum top-end with Mahle pistons, improved oiling, narrower valve angles, straightened intake and exhaust ports, lightened pushrods and rockers, and hydraulic lifters. Horsepower, torque and reliability were all up, emissions down. The new motor was unveiled to the public for the 1984 model year, and became an instant hit.

“A B-17 Flying Fortress of an engine that always feels like it’ll get you home, regardless. No, it doesn’t make an especially impressive amount of power. Until you’re out on the highway, that is, and grab a handful of throttle; then you smile as the bike surges ahead with no fuss, no bother, just a strong, steady pull,” I wrote of our Evo Softail testbike, then proceeded to get all gooey about the Harley’s signature exhaust note. “It’s a noise that somehow manages to combine romance and adventure and tradition into an off-beat cadence of throaty ka-chunks-and it does sound good.”

Says official company historian Dr. Martin Jack Rosenblum, “The Evolution engine changed everything. It was like Bob Dylan going electric at Newportthe switch from folk to rock-n-roll. Everything turned. Suddenly, our customers had vastly improved engines in their motorcycles. When we celebrate our bicentennial, 104 years from now, the Evolution will be seen as the engine that changed Harley-Davidson history and the entire heritage of motorcycling.”

Jingoistic hyperbole from a company man? I don’t think so.

Let’s look at the landscape of the early ’80s. Harley-Davidson had bought itself back from the dreaded AMF conglomerate-just in time for the bottom to fall out of the U.S. motorcycle market. With demand way down, Harley was forced to lay off 1600 of its 3800 employees. The Japanese, meanwhile, were cranking out new models (including an increasing number of cruisers) like there was no tomorrow. Many went unsold and began stacking up in warehouses; eventually there would be a full year’s inventory of leftover ’81, ’82 and ’83 models languishing. Harley, already on the brink, feared fire-sale clearance prices would spell its doom.

Management lobbied the International Trade Commission for increased tariffs on imported bikes over 700cc, arguing the impending price war would constitute “dumping,” a practice forbidden by U.S. trade laws. In past tariff petitions, this argument held no water simply because Harley had nothing that directly competed with the British in the 1950s, then the Japanese in the 1960s. This time, though, Harley rolled out plans for the modernized Evolution Big Twins and Sportsters. Tariffs granted.

With that breathing space, Harley went on to upgrade its facilities and improve production techniques. When the Evos proved a sales success, H-D was ready to crank up the assembly lines. Last year alone, 140,000 new Evolution-powered machines hit the streets.

If the Evo was The Motor That Saved Milwaukee, it also spawned a whole new sub-industry and served as a blueprint for other bike companies. Without the V2 would there be umpteen different clone-makers today, all with Evo lookalike motors? Would Polaris have embarked on the Victory project? Would the Hanlons have re-started Excelsior? Would investors have pumped in funds to resurrect Indian? Would BMW, of all companies, be selling a cruiser? Would Yamaha have an aircooled, pushrod V-Twin? You tell me.

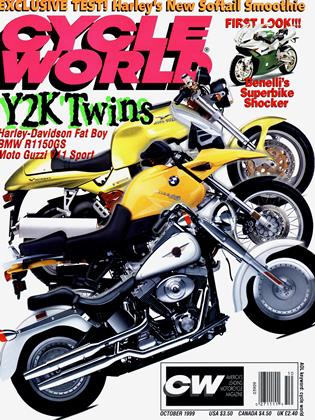

In any case, the Evo Big Twin is now history, phased out for Y2K to make room for a full line of Twin Cam 88s.

“The Evo has served us very, very well,” says Bruce Dennert, current manager of powertrain design and analysis. “It’s been a solid performer that’s made a lot of money for the company and lots of happy customers. There’s a million of them out there. It’ll be remembered fondly and always have a high place in the history of HarleyDavidson. It’s been a good old friend.”

Still is, really. Just like there was a lot of Shovelhead in the V2, there’s a lot of the V2 in the new Twin Cam 88. Think of it as an Evolution Evo.