On One Friday

UP FRONT

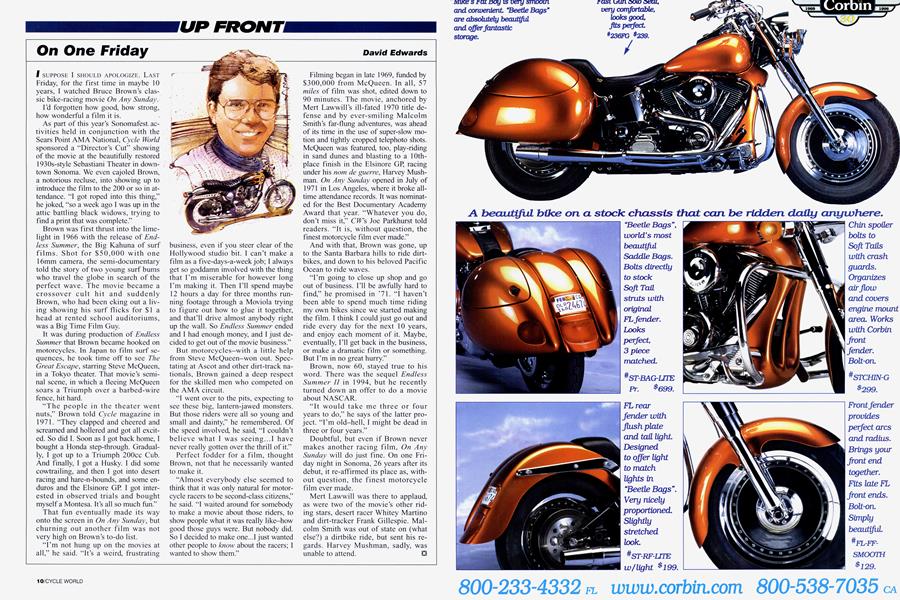

I SUPPOSE I SHOULD APOLOGIZE. LAST Friday, for the first time in maybe 10 years, I watched Bruce Brown's clas sic bike-racing movie On Any Sunday.~ I'd forgotten how good, how strong, how wonderful a film it is. As part of this year's Sonomafest ac tivities held in conjunction with the Sears Point AMA National, Cycle World sponsored a "Director's Cut" showing of the movie at the beautifully restored 1930s-style Sebastiani Theater in downtown Sonoma. We even cajoled Brown, a notorious recluse, into showing up to introduce the film to the 200 or so in at tendance. "I got roped into this thing," he joked, "so a week ago I was up in the attic battling black widows, trying to find a print that was complete."

Brown was first thrust into the lime light in 1966 with the release of End less Summer, the Big Kahuna of surf films. Shot for $50,000 with one 16mm camera, the semi-documentary told the story of two young surf bums who travel the globe in search of the perfect wave. The movie became a crossover cult hit and suddenly Brown, who had been eking out a liv ing showing his surf flicks for $1 a head at rented school auditoriums, was a Big Time Film Guy.

It was during production of Endless Summer that Brown became hooked on motorcycles. In Japan to film surf se quences, he took time off to see The Great Escape, starring Steve McQueen, in a Tokyo theater. That movie's semi nal scene, in which a fleeing McQueen soars a Triumph over a barbed-wire fence, hit hard.

"The people in the theater went nuts," Brown told Cycle magazine in 1971. "They clapped and cheered and screamed and hollered and got all excit ed. So did I. Soon as I got back home, I bought a Honda step-through. Gradual ly, I got up to a Triumph 200cc Cub. And finally, I got a Husky. I did some cowtrailing, and then I got into desert racing and hare-n-hounds, and some en duros and the Elsinore GP. I got inter ested in observed trials and bought myself a Montesa. It's all so much fun."

That tun eventually made its way onto the screen in On Any Sunday, but churning out another film was not very high on Brown's to-do list.

"I'm not hung up on the movies at all," he said. "It's a weird, frustrating business, even if you steer clear of the Hollywood studio bit. I can't make a film as a five-days-a-week job; I always get so goddamn involved with the thing that I'm miserable for however long I'm making it. Then I'll spend maybe 12 hours a day for three months runfling footage through a Moviola trying to figure out how to glue it together, and that'll drive almost anybody right up the wall. So Endless Summer ended and I had enough money, and I just de cided to get out of the movie business."

But motorcycles-with a little help from Steve McQueen-won out. Spec tating at Ascot and other dirt-track na tionals, Brown gained a deep respect for the skilled men who competed on the AMA circuit.

"I went over to the pits, expecting to see these big, lantern-jawed monsters. But those riders were all so young and small and dainty," he remembered. Of the speed involved, he said, "I couldn't believe what I was seeing.. .1 have never really gotten over the thrill of it."

Perfect fodder for a film, thought Brown, not that he necessarily wanted to make it.

"Almost everybody else seemed to think that it was only natural for motor cycle racers to be second-class citizens~' he said. "I waited around for somebody to make a movie about those riders, to show people what it was really like-how good those guys were. But nobody did. So I decided to make one...I just wanted other people to know about the racers; I wanted to show them."

Filming began in late 1969, funded by $300,000 from McQueen. In all, 57 miles of film was shot, edited down to 90 minutes. The movie, anchored by Mert Lawwill's ill-fated 1970 title de fense and by ever-smiling Malcolm Smith's far-flung adventures, was ahead of its time in the use of super-slow mo tion and tightly cropped telephoto shots. McQueen was featured, too, play-riding in sand dunes and blasting to a 10thplace finish in the Elsinore GP, racing under his nom de guerre, Harvey Mush man. On Any Sunday opened in July of 1971 in Los Angeles, where it broke all time attendance records. It was nominat ed for the Best Documentary Academy Award that year. "Whatever you do, don't miss it," CW's Joe Parkhurst told readers. "It is, without question, the finest motorcycle film ever made."

And with that, Brown was gone, up to the Santa Barbara hills to ride dirt bikes, and down to his beloved Pacific Ocean to ride waves.

"I'm going to close up shop and go out of business. I'll be awfully hard to find," he promised in `71. "I haven't been able to spend much time riding my own bikes since we started making the film. I think I could just go out and ride every day for the next 10 years, and enjoy each moment of it. Maybe, eventually, I'll get back in the business, or make a dramatic film or something. But I'm in no great hurry."

Brown, now 60, stayed true to his word. There was the sequel Endless Summer II in 1994, but he recently turned down an offer to do a movie about NASCAR.

"It would take me three or four years to do," he says of the latter pro ject. "I'm old-hell, I might be dead in three or four years."

Doubtful, but even if Brown never makes another racing film, On Any Sunday will do just fine. On one Fri day night in Sonoma, 26 years after its debut, it re-affirmed its place as, with out question, the finest motorcycle film ever made.

Mert Lawwill was there to applaud, as were two of the movie's other rid ing stars, desert racer Whitey Martino and dirt-tracker Frank Gillespie. Mal colm Smith was out of state on (what else?) a dirtbike ride, but sent his re gards. Harvey Mushman, sadly, was unable to attend.

David Edwards