Throttling up

TDC

Kevin Cameron

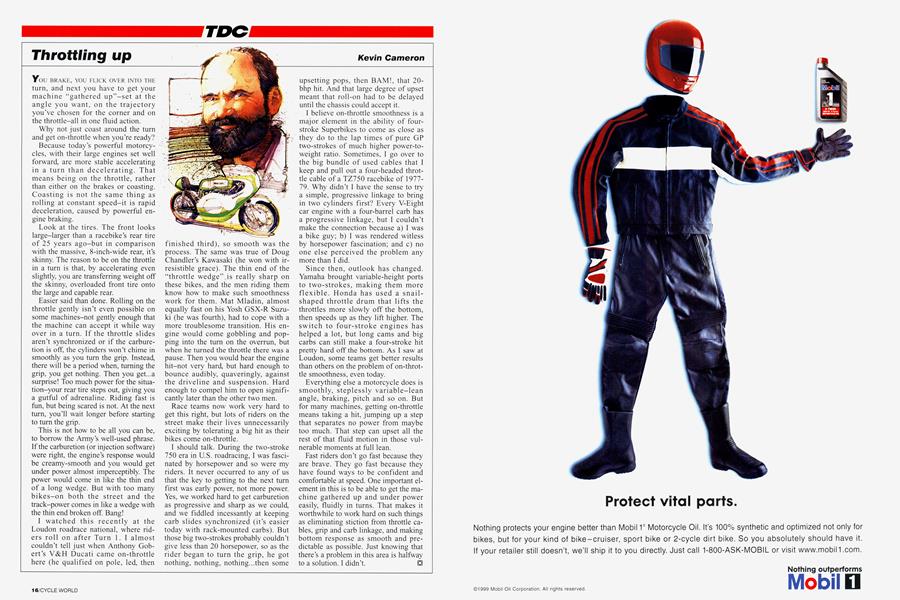

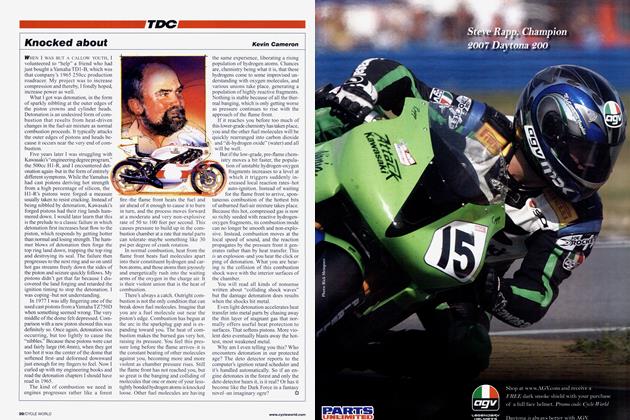

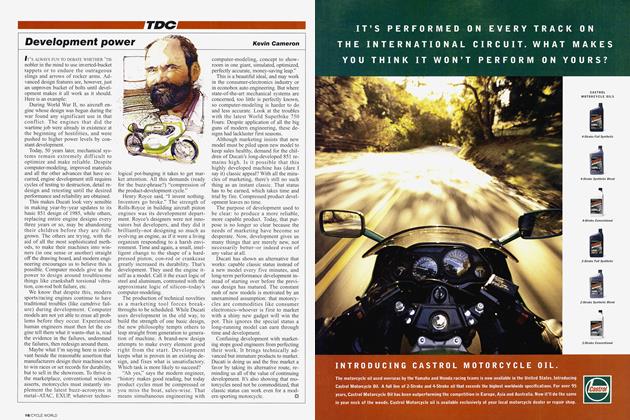

YOU BRAKE, YOU FLICK OVER INTO THE turn, and next you have to get your machine “gathered up”—set at the angle you want, on the trajectory you’ve chosen for the corner and on the throttle—all in one fluid action.

Why not just coast around the turn and get on-throttle when you’re ready?

Because today’s powerful motorcycles, with their large engines set well forward, are more stable accelerating in a turn than decelerating. That means being on the throttle, rather than either on the brakes or coasting. Coasting is not the same thing as rolling at constant speed-it is rapid deceleration, caused by powerful engine braking.

Look at the tires. The front looks large-larger than a racebike’s rear tire of 25 years ago-but in comparison with the massive, 8-inch-wide rear, it’s skinny. The reason to be on the throttle in a turn is that, by accelerating even slightly, you are transferring weight off the skinny, overloaded front tire onto the large and capable rear.

Easier said than done. Rolling on the throttle gently isn’t even possible on some machines-not gently enough that the machine can accept it while way over in a turn. If the throttle slides aren’t synchronized or if the carburetion is off, the cylinders won’t chime in smoothly as you turn the grip. Instead, there will be a period when, turning the grip, you get nothing. Then you get...a surprise! Too much power for the situation-your rear tire steps out, giving you a gutful of adrenaline. Riding fast is fun, but being scared is not. At the next turn, you’ll wait longer before starting to turn the grip.

This is not how to be all you can be, to borrow the Army’s well-used phrase. If the carburetion (or injection software) were right, the engine’s response would be creamy-smooth and you would get under power almost imperceptibly. The power would come in like the thin end of a long wedge. But with too many bikes-on both the street and the track-power comes in like a wedge with the thin end broken off. Bang!

I watched this recently at the Loudon roadrace national, where riders roll on after Turn 1. I almost couldn’t tell just when Anthony Gobert’s V&H Ducati came on-throttle here (he qualified on pole, led, then finished third), so smooth was the process. The same was true of Doug Chandler’s Kawasaki (he won with irresistible grace). The thin end of the “throttle wedge’\is really sharp on these bikes, and the men riding them know how to make such smoothness work for them. Mat Mladin, almost equally fast on his Yosh GSX-R Suzuki (he was fourth), had to cope with a more troublesome transition. His engine would come gobbling and popping into the turn on the overrun, but when he turned the throttle there was a pause. Then you would hear the engine hit-not very hard, but hard enough to bounce audibly, quaveringly, against the driveline and suspension. Hard enough to compel him to open significantly later than the other two men.

Race teams now work very hard to get this right, but lots of riders on the street make their lives unnecessarily exciting by tolerating a big hit as their bikes come on-throttle.

I should talk. During the two-stroke 750 era in U.S. roadracing, I was fascinated by horsepower and so were my riders. It never occurred to any of us that the key to getting to the next turn first was early power, not more power. Yes, we worked hard to get carburetion as progressive and sharp as we could, and we fiddled incessantly at keeping carb slides synchronized (it’s easier today with rack-mounted carbs). But those big two-strokes probably couldn’t give less than 20 horsepower, so as the rider began to turn the grip, he got nothing, nothing, nothing...then some upsetting pops, then BAM!, that 20bhp hit. And that large degree of upset meant that roll-on had to be delayed until the chassis could accept it.

I believe on-throttle smoothness is a major element in the ability of fourstroke Superbikes to come as close as they do to the lap times of pure GP two-strokes of much higher power-toweight ratio. Sometimes, I go over to the big bundle of used cables that I keep and pull out a four-headed throttle cable of a TZ750 racebike of 197779. Why didn’t I have the sense to try a simple, progressive linkage to bring in two cylinders first? Every V-Eight car engine with a four-barrel carb has a progressive linkage, but I couldn’t make the connection because a) I was a bike guy; b) I was rendered witless by horsepower fascination; and c) no one else perceived the problem any more than I did.

Since then, outlook has changed. Yamaha brought variable-height ports to two-strokes, making them more flexible. Honda has used a snailshaped throttle drum that lifts the throttles more slowly off the bottom, then speeds up as they lift higher. The switch to four-stroke engines has helped a lot, but long cams and big carbs can still make a four-stroke hit pretty hard off the bottom. As I saw at Loudon, some teams get better results than others on the problem of on-throttle smoothness, even today.

Everything else a motorcycle does is smoothly, steplessly variable-lean angle, braking, pitch and so on. But for many machines, getting on-throttle means taking a hit, jumping up a step that separates no power from maybe too much. That step can upset all the rest of that fluid motion in those vulnerable moments at full lean.

Fast riders don’t go fast because they are brave. They go fast because they have found ways to be confident and comfortable at speed. One important element in this is to be able to get the machine gathered up and under power easily, fluidly in turns. That makes it worthwhile to work hard on such things as eliminating stiction from throttle cables, grip and carb linkage, and making bottom response as smooth and predictable as possible. Just knowing that there’s a problem in this area is halfway to a solution. I didn’t.