RACE WATCH

WORLD WARS

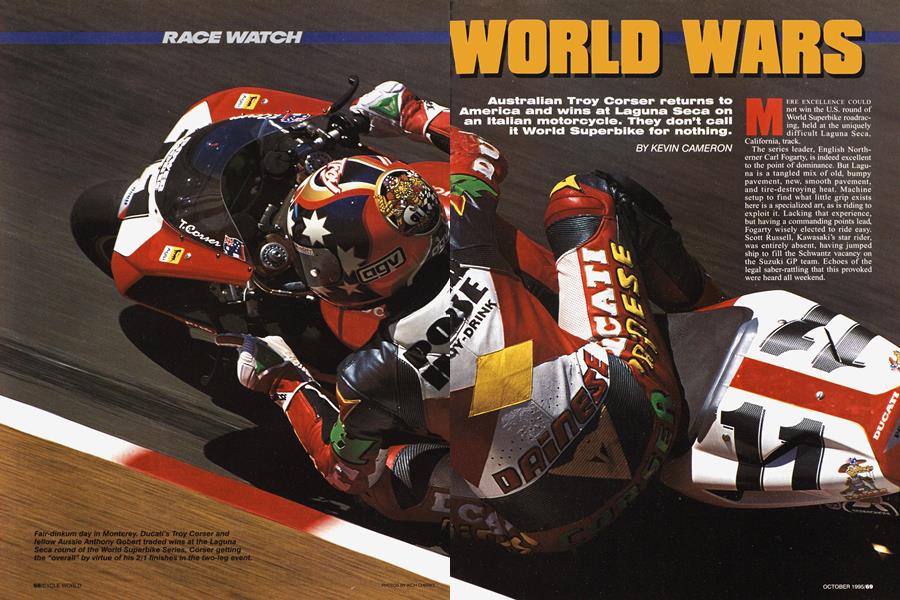

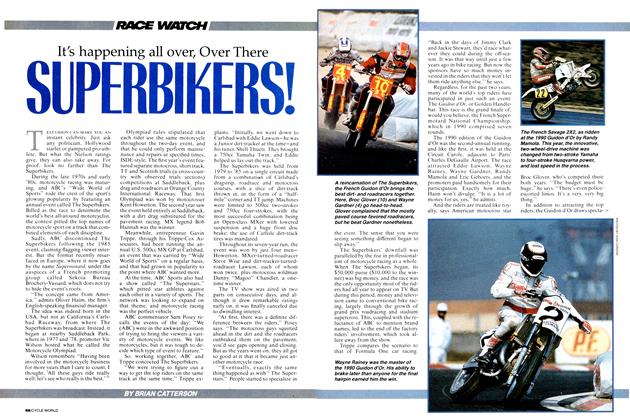

Australian Troy Corser returns to America and wins at Laguna Seca on an Italian motorcycle. They don’t call it World Superbike for nothing.

KEVIN CAMERON

MERE EXCELLENCE COULD not win the U.S. round of World Superbike roadracing, held at the uniquely difficult Laguna Seca, California, track.

The series leader, English Northerner Carl Fogarty, is indeed excellent to the point of dominance. But Laguna is a tangled mix of old, bumpy pavement, new, smooth pavement, and tire-destroying heat. Machine setup to find what little grip exists here is a specialized art, as is riding to exploit it. Lacking that experience, but having a commanding points lead, Fogarty wisely elected to ride easy. Scott Russell, Kawasaki’s star rider, was entirely absent, having jumped ship to fill the Schwantz vacancy on the Suzuki GP team. Echoes of the legal saber-rattling that this provoked were heard all weekend.

World Superbike is the premier roadracing series for productionbased four-stroke machines. But this event was extra-special, a rare confluence of two streams; top riders from our own AMA National Superbike series would try their strength against these world teams, their factory-developed motorcycles and their veteran riders. The paddock area mirrored the confrontation-World teams on one side, AMA teams on the other.

World Superbike gets the best of everything, as the American teams discovered when they were issued tires better than anything they get here. Better grip was fine, but two days couldn't fit it into mature machine setups. Oh, just because Americans dominate Daytona, don’t think WSB isn't fast. It is. Eventual pole-sitter Troy Corser (Promotor Ducati) would lower the May 1995 AMA Laguna lap record by an astounding 1.9 seconds.

The gripless Laguna surface gave the early advantage to our national riders—and to others with Laguna experience. It would stay that way to the end. Fresh-faced Anthony Gobert, who won race one and came second in race two (WSB runs MX-style, two-leg events), has tested extensively at Laguna on his WSB Mu/./y Kawasaki. Troy Corser, who won race two and was second in race one, was U.S. Superbike champ last year and knows Laguna well.

Both of these Australians have the best machinery their factories can provide, so it was an unexpected pleasure to see American Honda/Smokin' Joe's riders Mike Hale and Miguel Duhamel fill the next two places in both races on their not-quite-faetory RC45s. These men rode brilliantly, Duhamel holding second for a Ion time in race one, and Hale pullin away from everyone while his tire lasted in race two. The RC'45 is the most improved machine of the AMA series. A year ago at Daytona, the American Honda crew fumed as factory technicians ignored their problems, leaving them lost in midfield. Now the roles are reversed; the U.S.built RCs at Laguna were clearly superior to those provided to WSB riders Aaron Slight and Simon Crafar.

There is another contest here, of course; the one between the Italian one-liter V-Twins and everyone else, on 75()cc Fours. Rob Muzzy observed that since the beginning of WSB, Ducati has amassed 100 wins. “Whoever is second," he continued, “has somewhere in the 20s." He was careful not to say there is anything improper about this—just that it is a fact.

1 believe most motorcyclists will agree the return of Ducati and a genuine European presence in motorcycle racing are good. All agree that the present 916 Ducati (or 955, 989, 997 or whatever it is on a given day) is a great achievement, especially for a small company. Yet there is a growing sharpness in the discussion of how to factor Twins and Fours into competitive balance.

“Last year, Honda came in with a big budget, and they didn’t do shit,” Muzzy observed. “This year, Yamaha came with a budget that’s at least four times what we’re spending. And one of their guys comes over to me and says, ’Hey, this is impossible’.”

“Welcome to the real world,” Muzzy replied.

In this particular real world, the 750 Fours can match or even exceed the peak horsepower of the 916-plus Ducatis, but only at a cost. The Ducatis are optimized for acceleration, with adequate but not lightningquick handling. To equal them on the track, the 750 Fours must push to extremes in every department-revs (enough to give durability problems), powerband (narrow, sometimes sudden, often hard on tires), steering (quick to the point of instability).

Meanwhile the Red Tide of Ducatis made up 40 percent of the Laguna field, and few of them are slow. The next FIM Congress (where the rules are made) should be a dilly.

To make their bikes hook up over Laguna’s choppy pavement, several teams tried soft springs and damping. This softness, combined with Laguna’s infamous corner-exit bumps, produced out-of-control wallowing, so the soft springs were quickly put away again. Because the Ducatis took these bumps in stride, I asked Öhlins suspension rep Jon Cornwell if the Europeans generally set their bikes up rather stiff.

“Just the opposite,” he replied. “The Europeans hate the feeling of that seat hitting them hard. In fact, the Kawasakis are the only bikes here using springs even close to what Öhlins would recommend. And the Yamahas have the same springs we’d use on a 250.”

So I looked again, and I learned something. Riders off the gas wallow over the bumps. Riders on the gas just go ka-bump over them, no problem.

As track confidence improved riders used more throttle, and the wallowing disappeared. Why? As the rider twists the throttle, the engine pulls harder on the drive chain, especially in lower gears on this slow circuit. Chain pull generates a tangent force that drives the rear wheel down. Those Ducatis looked stiff across bumps because their rear suspensions were toppedhard-by chain-pull force.

The last WSB round I saw was Braincrd, in the late ’80s, an event that fairly exuded community. There was a feeling of all being in the game together, of wanting the series to succeed, even of helping one another. It was open and pleasant, like club racing. By contrast, the tents, lips and faces in CiP racing are closed. At Laguna, change was evident. WSB isn't closed yet, but the process has begun. Success does that.

Many people expect the manufacturers to leave two-stroke GP racing, race what they sell and back WSB in a big way. The grids are full, the competition is close and the show is a dandy. Why hasn’t it happened? I asked Steve Whitelock, Yvon Duhamel’s mechanic from the early ’70s and for many years an agent in Honda’s European racing programs.

“Look around. How many Japanese staff do you see?” he asked. I had to admit there weren’t many.

“That’s the gauge of their seriousness-how many engineers they send,” Whitelock added, dismissing the subject.

So it’s up to the Japanese. Right now, they like GP racing, so GP racing it is. If they change their collective

minds, WSB may get the nod. Therefore, enjoy WSB for what it is-a great series at a somewhat different levelnot mourn for what isn’t. GP racing is far from dead, and it’s not clear that the Japanese companies would choose to race 750s if they did go productionbased racing; 600 Supersport is a pretty lively place these days.

One thing is for sure. Even production-based racing has become very, very expensive«. You need the bike, plus the race kit, plus the kit for the kit, plus the pieces that don’t exist. And so motorcycle racing continues its march away from informality and sport, toward a purely business status.

Each motorcycle has a different way of responding to sudden traction loss as its rider feels for the limit. When one of the Hondas breaks traction, accelerating out of a corner, the engine gets away momentarily, the rear end slides out, and the bike “gallops”—it oscillates sharply. But when a Kawasaki is pushed hard, you hear a very slow oscillation of engine speed as the tire eases loose, grips again smoothly, and eases loose again-a controllable traction loss. The Yamaha engines shriek but don’t seem to hook up. The Ducatis break away very little—probably because their powerbands are benign and their flywheels keep engine revs from getting away. But their higher stability carries a price; you can see that rolling them over takes heavy effort. Ducatis don’t flick.

These differences tempered my observation of practice. Although Gobert, Corser and Hale could all run pretty equal times, 1 thought about how easy or hard those laps would be to maintain over time. Just on the basis of what 1 saw on the track, I rather favored Gobert. Harley race boss Steve Scheibe (at Laguna as observer this time) picked Corser. Among our national riders, Hale was the choice. But it was clear that the race would be easiest for Corser, somewhat harder for Gobert, whose bike showed more temperament the harder he went, and a severe endurance test for Hale on the galloping Honda. The Yamahas, shrieking as they spun in their quest for traction, might not be in the hunt. Yasutomo Nagai and Colin Edwards, on WSB Yams, did qualify fourth and sixth, but finding even that good a setup had been harrowing.

Laguna is famous for its Corkscrew, a left-right pair of turns draped over a steep hillside. The unwary try to pitch over as they roll left, a big mistake that produces crazy motions from bikes and often, a hard slap on the ground. As riders exit the bottom of this madness, they must roll from right to left quickly enough to be positioned for a fast, accelerating downhill. Ciobert was fascinating here, for he snapped his machine upright very fast, then hesitated an instant before slapping it down for the left. The entire maneuver was very quick—certainly quicker than the Ducati crowd could achieve. Freddie Spencer on the Ferracci machine was content to let his machine eat all the track it wanted as he rolled it over in leisurely fashion, ending up entering the downhill left on the inside.

Why was Ciobert hesitating at the top of his roll? Another Kawasaki came through whose rider was trying hard. Striving for a single, power-on rollover, he succeeded only in provoking an upsetting wiggle in mid-maneuver. Aha, I thought, Ciobert is letting his chassis unwind where it can't hurt him, then continuing the maneuver. I remembered Dale Quarterley, saying that with the Kawasaki, you can't make a sudden maneuver when the chassis is wound up. After the race, I asked Ciobert about the pause.

“The bike doesn’t like to roll over with the power on," he replied.

Even with the pause, Ciobert was making his bike flick quicker than the competition. By letting it unwind, accepting that tiny delay in the middle, he was able to obtain a quicker rollover that left him better set for the downhill section-where, by the way, he pulled distance every lap in the race.

In race one, Gobert took the lead on the second lap, with Miguel Duhamel on the Honda in second for the next 10 circuits. Corser eventually got by, and spent the remainder of the race poised on Gobert ’s back wheel, seemingly waiting to spring a carefully planned pass. Gobert made zero mistakes and Corser stayed put until the last moment—when his pass was adroitly turned into a cross-over repass by Gobert. Duhamel’s tire had faded out badly after 20 laps of staying near the lead pair. The final order was Gobert, Corser, then Duhamel back 6 seconds, Hale back another 5. In fifth was the patient Fogarty.

After a long, long intermission, race two began, with Mike Hale seizing the lead and pulling quickly away. It was too good to last. Hale’s moment of glory was lap three, after which his fading tire abandoned him to Gobert and Corser. Hale stuck gamely to the lead pair, just as Miguel had done in race one, only to have his bike’s handling turn vicious as the tire slowly deteriorated, forcing him to drop back rapidly after about L20. Corser meanwhile asserted himself, taking over on LÍ l, pulling away to win by 6 seconds. Yamaha’s Nagai tenaciously extracted a fifth. The watch showed that overall winner Corser had not gone faster; Gobert had gone slower. Times for the two 29-lap races differed by only 3/io of a second.

The big what-if of these races was this: How would Hale and Duhamel have fared had they been with the series all year, and had known how to set up their bikes to make the top tires last? Rumors about these men’s futures colored most post-race conversations.

An inkling of the technological future could be heard every time Gobcrt’s Kawasaki was started; the engine sound announced that this bike has gear-driven cams instead of the standard silent chain. That, in turn, suggests that next year’s new ZX-7 engine will also use gears—to better control valve motion at even higher revs. The bore will grow, the stroke will shrink, and the current 14,700rpm limiter setting will move on up. There are mutterings of a Twin from Honda. A new GSX-R750 is coming from Suzuki. Ducati won’t sit still. Endless fascination. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue