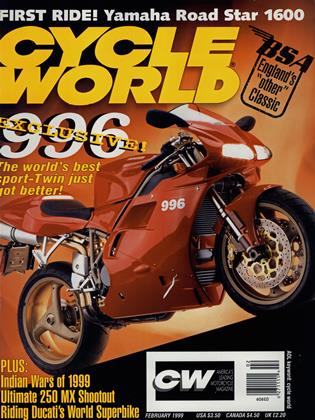

COME-LATELY CLASSICS

England’s other collectible

KEVIN CAMERON

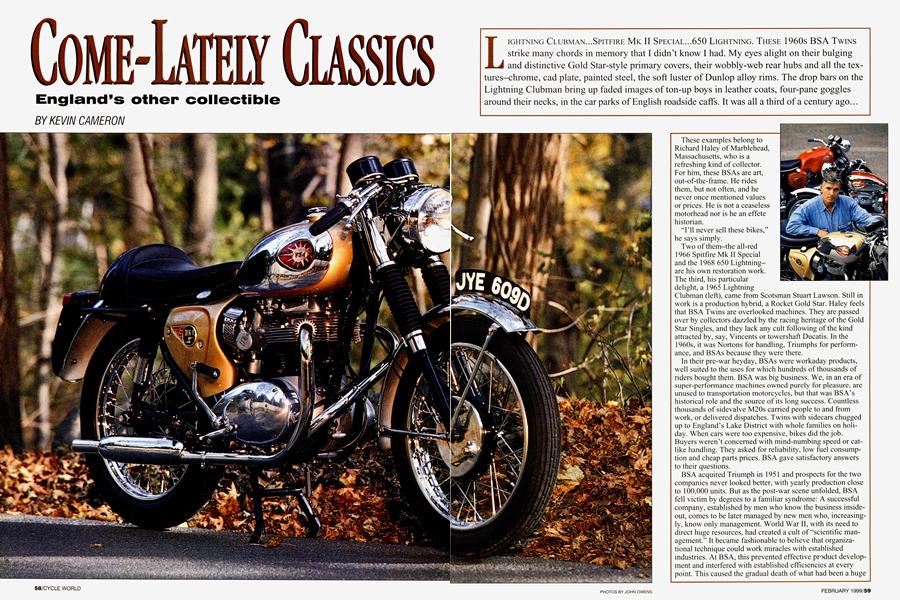

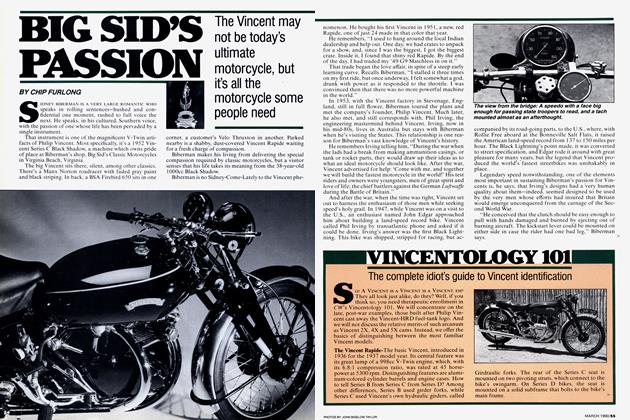

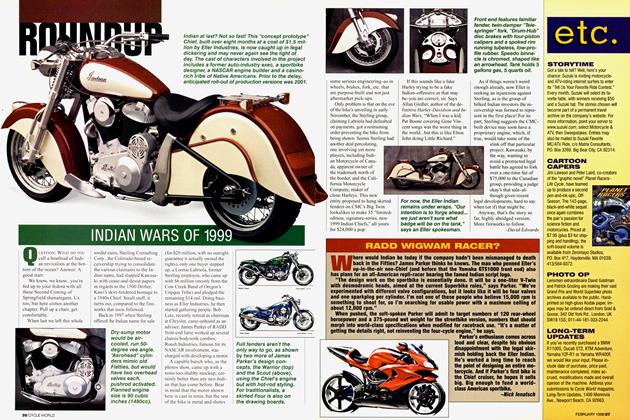

LIGHTNING CLUBMAN...SPITFIRE MK II SPECIAL...650 LIGHTNING. THESE 1960s BSA TWINS strike many chords in memory that I didn't know I had. My eyes alight on their bulging and distinctive Gold Star-style primary covers, their wobbly-web rear hubs and all the textures-chrome, cad plate, painted steel, the soft luster of Dunlop alloy rims. The drop bars on the Lightning Clubman bring up faded images of ton-up boys in leather coats, four-pane goggles around their necks, in the car parks of English roadside caffs. It was all a third of a century ago...

These examples belong to Richard Haley of Marblehead,

Massachusetts, who is a refreshing kind of collector.

For him, these BSAs are art, out-of-the-frame. He rides them, but not often, and he never once mentioned values or prices. He is not a ceaseless motorhead nor is he an effete historian.

‘TT1 never sell these bikes,” he says simply.

Two of them-the all-red 1966 Spitfire Mk II Special and the 1968 650 Lightningare his own restoration work.

The third, his particular delight, a 1965 Lightning Clubman (left), came from Scotsman Stuart Lawson. Still in work is a production hybrid, a Rocket Gold Star. Haley feels that BSA Twins are overlooked machines. They are passed over by collectors dazzled by the racing heritage of the Gold Star Singles, and they lack any cult following of the kind attracted by, say, Vincents or towershaft Ducatis. In the 1960s, it was Nortons for handling, Triumphs for performance, and BSAs because they were there.

In their pre-war heyday, BSAs were workaday products, well suited to the uses for which hundreds of thousands of riders bought them. BSA was big business. We, in an era of super-performance machines owned purely for pleasure, are unused to transportation motorcycles, but that was BSA’s historical role and the source of its long success. Countless thousands of sidevalve M20s carried people to and from work, or delivered dispatches. Twins with sidecars chugged up to England’s Lake District with whole families on holiday. When cars were too expensive, bikes did the job.

Buyers weren’t concerned with mind-numbing speed or catlike handling. They asked for reliability, low fuel consumption and cheap parts prices. BSA gave satisfactory answers to their questions.

BSA acquired Triumph in 1951 and prospects for the two companies never looked better, with yearly production close to 100,000 units. But as the post-war scene unfolded, BSA fell victim by degrees to a familiar syndrome: A successful company, established by men who know the business insideout, comes to be later managed by new men who, increasingly, know only management. World War II, with its need to direct huge resources, had created a cult of “scientific management.” It became fashionable to believe that organizational technique could work miracles with established industries. At BSA, this prevented effective product development and interfered with established efficiencies at every point. This caused the gradual death of what had been a huge group of companies, with interests in metals, machine tools, weapons and automobiles.

What were the origins of the \ BSA Twins? The prolific Valentine Page made the initial layout in 1939, with the characteristic bolted-on gearbox. It would benefit from the negative example of Triumph’s Speed Twin-veteran engineer Bert Hopwood described the Triumph, with its two cams and five gears, as a “rattler.” Page therefore gave the new BSA a quieter single cam, located behind the cylinder block so as to improve exhaustarea cooling. The engine had a bolted-on rocker box.

War prevented the BSA’s production, but promptly thereafter, Chief Designer Herbert Perkins and the tech department’s D.W. Munro pushed the 500cc A7 for a September, 1946, introduction. The 6.6:1 compression, 62 x 82mm engine, with iron cylinder and head but aluminum cases, made 26 horsepower at 6000 rpm. It had a light, rigid frame and a Page-designed telescopic fork. Two years later, a tuned version with 7.5 compression and twin carbs made 31 bhp.

Like the Speed Twin before it, this was a 360-degree motor with only two main bearings.

There was no crank support between the two rod journals, just the usual substantial flywheel. Vibration was considerable, but overbalancing with heavy crank counterweights shifted the axis of vibration from vertical (objectionable) to fore-and-aft (less so).

In 1949, Bert Hopwood arrived from Triumph, and was charged with the addition of a 70 x 84mm 650cc model, the A10. For thermal efficiency, he reduced combustion chamber surface area with a narrower valve angle. Cylinder cooling was enhanced by improved between-the-bores airflow. The stroke was long, limiting revs to about 5700, but the engine could pull a sidecar. In 1951, he revamped the A7 as well, moderating bore and stroke to 66 x 72.6mm and also addressing a problem of sticking exhaust valves.

In the post-war period, production racing flowered in England. As BSA Gold Star Singles won every Isle of Man Clubmans TT from 1949-56, they also became a mainstay of U.S. dirt-track racing.

In one of the early ’50s Daytona races, though, many Gold Stars suffered gearbox failure. This had to be set right, and not just mechanically. In 1952, factory-prepared BSA Star Twins arrived with 7.9:1 compression, Lucas racing magnetos and 1 Vió-inch (27mm) Amal TT carbs, plus aluminum rims. Thirteen Stars started and 10 finished, six in the top 20. Encouraging. In 1954, three Singles and three Twins (now with separate gearboxes, allowing wider choice of ratios) were sent from the factory to the famous beach race. Harley, through the AMA, sought to have them barred, but adroit legal and public-relations threats from BSA’s West Coast importer, Hap Alzina, won the day. The BSAs filled the top five places, with Bobby Hill the winner. Later that season, Kenny Eggers won a 125-mile roadrace at Willow Springs, California, on a BSA Twin.

The following year these successes were commemorated by the new 500cc Shooting Star model, with aluminum head, 7.25 compression and a Monobloc carb.

As in England, Gold Stars attracted most of the attention from riders, tuners and the aftermarket, so the Twins faded from racing prominence. Later, as BSA was converting its Twins to unit construction as the A50/A65, it phased out the Gold Star (1962-64). Its replacement would be the 441 Victor, a motocrosser that never came close to the Gold Star’s versatility.

A byproduct of this changeover was the Rocket Gold Star. Former racer Eddie Dow offered a line of racing goodies for the Gold Star, and when it was discontinued he suggested mating existing stocks of Super Rocket Twins with Gold Star chassis. Original RGS chassis are identifiable by their lack of the kink in the lower right frame rail that provided clearance for the Single’s oil pump. Some 680 of these super-sporting hybrids were built in the 1962-63 period. The 46-bhp engines sported dual Amal Monoblocs.

Another interesting limited-production sporting BSA was the 1964-65 Lightning Clubman, of which only 200 were built and fewer than 40 remain. These were available only through certain home-market dealers, their engines reputedly individually dynoed. Power? Cycle World's road test of the 1964 Lightning Rocket (same motor, different package) listed a claimed 56 bhp at 7000 rpm.

The Lightning Clubman was the “Mk I” that led to the next year’s Spitfire Mk II Special. The Mk U’s highly tuned 75 x 74mm 650 had serious 10.5:1 compression, twin 29mm Amal GP racing carbs, closer-ratio gears and a claimed 53-55 bhp. Owner Haley reminds us that this model was sold as the “World’s Fastest Production Motorcycle,” known in England as the “Bonnie-beater.” His machine is the English-market model, with a large, racing-style 5-gallon fiberglass tank.

Cycle World's 1966 road test pushed a 416-pound U.S.spec Mk II through the lights in 14.9 seconds at 89 mph. Dreary? That was the year of BSA’s infamous “rogue spark” problem, in which defective points cams led to overheating and poor performance as a result of secondsparking. The following year, with this corrected and the racy GPs replaced by bigger 32.5mm Concentric carbs, the Mk III went 14.3 at 95 mph.

The U.S. market’s constant demand for more performance was something new in BSA experience, requiring continuous, careful development of a kind that cost-conscious management did not support. Pre-unit BSA Twins had been paragons of reliability, but the unit engines were, according to Hopwood, rushed to market with inadequate development. Their declining reliability put a sharp tang of truth in the skeptics’ claim that BSA stood for “Bastard Stopped Again.” Still, contemporary airflow specialist Kenny Augustine speaks highly of the midrange of early, small-port unit 650s.

Triumph Twins went on to establish a fine reputation, both because of their Daytona wins (1962, ’66, ’67) and because, once their geometry and front-fork action were corrected in 1962-63, of their fine handling. Don Brown, formerly VP of BSA here in the U.S., recalls that the West Coast Triumph importer, Johnson Motors, worked hard to get its machines into movies and into the hands of popular Hollywood stars. It worked as well then as it works today for Harley. “If you were somebody, you rode a Triumph,” he observes today.

BSAs, with their generous chrome, gaudy badging and trademark Flamboyant Red paint, appealed more to “guys with T-shirts and tattoos,” as one friend and former Super Rocket owner remembered recently.

Reliability troubles-often with the drive-side main roller bearing-sapped the tolerance of BSA owners and dealers alike. On one occasion, Brown was obliged to ship 4000 machines back to England for re-work. Only the factory could strip and repair a problem this big.

Meanwhile, BSA management went from one scientific reorganization scheme to another in an end-game of “deckchair chess aboard the Titanic.” Each move must have made sense in someone’s view, but there were too many someones, and they knew too little about the motorcycle business. Time and reputation leaked away. As sales fell, the scale of the factories themselves became a liability, as their break-even point was high.

Many of the projects attempted at BSA-lightweight motorcycles, step-throughs and scooters-were responses to real markets, and might have succeeded if acted upon decisively. Unfortunately, the scooters came late and failed to meet Italian competition, while no definitive lightweight was ever produced. Instead, the Triumph Cub, a.k.a. the “big-end eater,” already mechanically weak from overenlargement, was expanded yet again to create that great embarrassment, the BSA 250. Again and again, projects were tooled before they were proven in development. They had to be withdrawn once problems appeared in the field, or were delivered with a blizzard of service bulletins.

Dealers resented doing the company’s engineering work.

The Japanese makers, beginning with small machines in the late 1950s and early ’60s, began to move up. BSA, with nothing to offer now but large machines, had played themselves into a comer. Today we see these bikes as charming artifacts of a simpler age, but to buyers at the time, they were vibrating, outdated and oily by comparison with Japanese alternatives. One owner quipped to me at the time, giving his machine a slap on the tank, “It may be slow, but at least it’s unreliable.”

Meanwhile, Honda offered its 1966 electric-start dohc CB450 and Suzuki introduced its X-6 Hustler 250-both as fast as all but the very top British Twins, and priced to sell. Behind them came the deluge. BSA had only one card left to play. That was the 750 Rocket-3, a concept first proposed by Hopwood in 1961, when there was still time. As he saw it, the demand for performance required larger displacement in a lower-vibration format. Bigger Twins would just be bigger shakers, so a 750 Triple, using Triumph 500 Twin components, was a natural solution. This bike was finally prototyped in 1965, looking and performing like a more muscular Bonneville. Management transformed this into the unlovely Triumph Trident and BSA Rocket-3 of 1969, with their strange “raygun” mufflers, angular tanks and excessive seat heights. Only when production reverted to something nearer the prototype did the Triples begin to move.

When the Rob North-framed Trident/Rocket-3 factory roadracer covered itself with glory in 1970-71, a production replica would have sold out; this compact and appealing design still looks modem today. The opportunity passed. By then Honda was pouring forth CB750 Fours; Kawasaki followed in 1973 with the 900 Z-l-both machines becoming instant classics. The last launch window had closed. As the once-proud British industry let markets fall from its weakening grasp, the Japanese politely picked them up.

Catastrophe came in 1971, in the form of an oil-carrying backbone chassis that raised Twin seat heights 3 inches. Buyers said no. BSA Twin production ended that year, Triples a year later. The End.

Or is it? What remains of the mighty BSA properties now exists as BSA-Regal, and the name has been applied to British-made, period-styled 400cc Singles that have, in supreme irony, sold well in Japan. Maybe there’s a future of a kind here.

Haley’s Lightning Clubman received the Participants’ Choice and Concours of Excellence trophies at the recent Larz Andersen Museum Show. Could this indicate a change of official attitudes toward the BSA brand? Mr. Haley is pleased in a calm sort of way.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontUps & Downs, 1998

February 1999 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Great Book Explosion

February 1999 By Peter Egan -

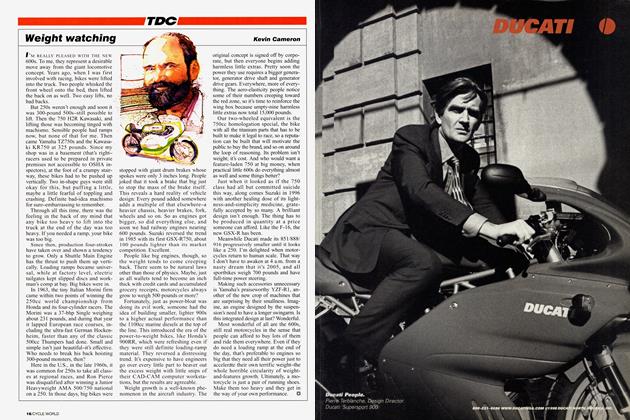

TDC

TDCWeight Watching

February 1999 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1999 -

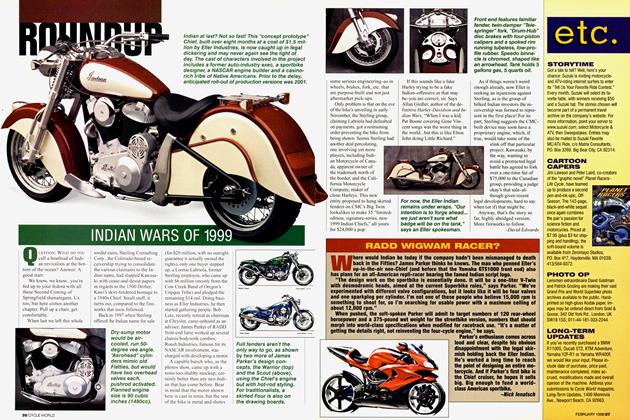

Roundup

RoundupIndian Wars of 1999

February 1999 By David Edwards -

Roundup

RoundupRadd Wigwam Racer?

February 1999 By Nick Lenatsch