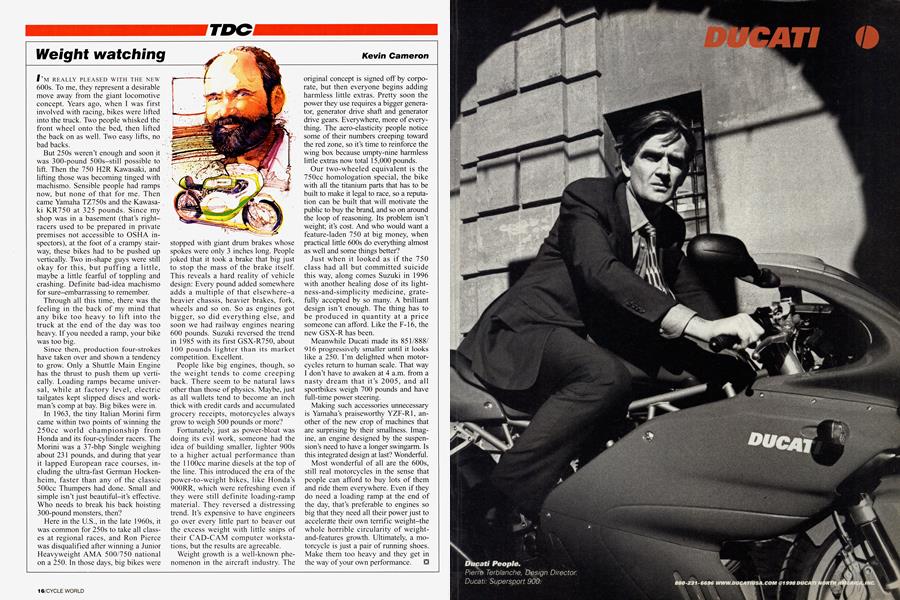

Weight watching

TDC

Kevin Cameron

I’M REALLY PLEASED WITH THE NEW 600s. To me, they represent a desirable move away from the giant locomotive concept. Years ago, when I was first involved with racing, bikes were lifted into the truck. Two people whisked the front wheel onto the bed, then lifted the back on as well. Two easy lifts, no bad backs.

But 250s weren’t enough and soon it was 300-pound 500s—still possible to lift. Then the 750 H2R Kawasaki, and lifting those was becoming tinged with machismo. Sensible people had ramps now, but none of that for me. Then came Yamaha TZ750s and the Kawasaki KR750 at 325 pounds. Since my shop was in a basement (that’s rightracers used to be prepared in private premises not accessible to OSHA inspectors), at the foot of a crampy stairway, these bikes had to be pushed up vertically. Two in-shape guys were still okay for this, but puffing a little, maybe a little fearful of toppling and crashing. Definite bad-idea machismo for sure-embarrassing to remember.

Through all this time, there was the feeling in the back of my mind that any bike too heavy to lift into the truck at the end of the day was too heavy. If you needed a ramp, your bike was too big.

Since then, production four-strokes have taken over and shown a tendency to grow. Only a Shuttle Main Engine has the thrust to push them up vertically. Loading ramps became universal, while at factory level, electric tailgates kept slipped discs and workman’s comp at bay. Big bikes were in.

In 1963, the tiny Italian Morini firm came within two points of winning the 250cc world championship from Honda and its four-cylinder racers. The Morini was a 37-bhp Single weighing about 231 pounds, and during that year it lapped European race courses, including the ultra-fast German Hockenheim, faster than any of the classic 500cc Thumpers had done. Small and simple isn’t just beautiful-it’s effective. Who needs to break his back hoisting 300-pound monsters, then?

Here in the U.S., in the late 1960s, it was common for 250s to take all classes at regional races, and Ron Pierce was disqualified after winning a Junior Heavyweight AMA 500/750 national on a 250. In those days, big bikes were stopped with giant drum brakes whose spokes were only 3 inches long. People joked that it took a brake that big just to stop the mass of the brake itself. This reveals a hard reality of vehicle design: Every pound added somewhere adds a multiple of that elsewhere-a heavier chassis, heavier brakes, fork, wheels and so on. So as engines got bigger, so did everything else, and soon we had railway engines nearing 600 pounds. Suzuki reversed the trend in 1985 with its first GSX-R750, about 100 pounds lighter than its market competition. Excellent.

People like big engines, though, so the weight tends to come creeping back. There seem to be natural laws other than those of physics. Maybe, just as all wallets tend to become an inch thick with credit cards and accumulated grocery receipts, motorcycles always grow to weigh 500 pounds or more?

Fortunately, just as power-bloat was doing its evil work, someone had the idea of building smaller, lighter 900s to a higher actual performance than the 1 lOOcc marine diesels at the top of the line. This introduced the era of the power-to-weight bikes, like Honda’s 900RR, which were refreshing even if they were still definite loading-ramp material. They reversed a distressing trend. It’s expensive to have engineers go over every little part to beaver out the excess weight with little snips of their CAD-CAM computer workstations, but the results are agreeable.

Weight growth is a well-known phenomenon in the aircraft industry. The original concept is signed off by corporate, but then everyone begins adding harmless little extras. Pretty soon the power they use requires a bigger generator, generator drive shaft and generator drive gears. Everywhere, more of everything. The aero-elasticity people notice some of their numbers creeping toward the red zone, so it’s time to reinforce the wing box because umpty-nine harmless little extras now total 15,000 pounds.

Our two-wheeled equivalent is the 750cc homologation special, the bike with all the titanium parts that has to be built to make it legal to race, so a reputation can be built that will motivate the public to buy the brand, and so on around the loop of reasoning. Its problem isn’t weight; it’s cost. And who would want a feature-laden 750 at big money, when practical little 600s do everything almost as well and some things better?

Just when it looked as if the 750 class had all but committed suicide this way, along comes Suzuki in 1996 with another healing dose of its lightness-and-simplicity medicine, gratefully accepted by so many. A brilliant design isn’t enough. The thing has to be produced in quantity at a price someone can afford. Like the F-16, the new GSX-R has been.

Meanwhile Ducati made its 851/888/ 916 progressively smaller until it looks like a 250. I’m delighted when motorcycles return to human scale. That way I don’t have to awaken at 4 a.m. from a nasty dream that it’s 2005, and all sportbikes weigh 700 pounds and have full-time power steering.

Making such accessories unnecessary is Yamaha’s praiseworthy YZF-R1, another of the new crop of machines that are surprising by their smallness. Imagine, an engine designed by the suspension’s need to have a longer swingarm. Is this integrated design at last? Wonderful.

Most wonderful of all are the 600s, still real motorcycles in the sense that people can afford to buy lots of them and ride them everywhere. Even if they do need a loading ramp at the end of the day, that’s preferable to engines so big that they need all their power just to accelerate their own terrific weight-the whole horrible circularity of weightand-features growth. Ultimately, a motorcycle is just a pair of running shoes. Make them too heavy and they get in the way of your own performance.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue